RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

TOSSING on the long rollers, Clem Carey's little cat-boat looked a mere dot in the immensity of gray sea and stormy sky. Caught off the Florida coast by a sudden storm, he had been drifted out of sight of land, and all night had been bailing for dear life. Now a second storm was blowing up and Clem, glancing at the scud of cloud, shook his head. "This is the finish," he said briefly.

He was aching all over, his eyes were sore with lack of sleep, and if he had not been as hard as nails, he would never have lasted so long as he had. A great wave tossed him high, and suddenly a dark shape loomed out of the storm drift behind him. She was a schooner, evidently motor driven, for with hardly a rag of sail she was forging rapidly onwards.

Clem gave a hoarse shout, and standing up waved frantically. Then he was in the trough again and lost sight of the ship. The suspense of the next few minutes was horrible, for the chances seemed all against those aboard the schooner seeing anything so small as the tiny cat-boat in the heavy sea. But at last he got an answering wave from the rail of the ship, and breathed a prayer of gratitude as he saw her shift helm in his direction. Soon she was close above him. "Catch hold," cried a harsh voice, and a coil of line hissed over him. Clem caught it, made fast, and was dragged alongside.

"Can you get my boat aboard?" he asked.

"Your boat," roared the voice with an oath. "What do you think this is—a floating dockyard? Cut her loose and get aboard sharp, or stay with her and drown if you want to."

It hurt Clem like a blow to see his boat go, for she was almost the only thing he owned in the world. But there was no help for it, and as he scrambled over the rail he saw her drift into the schooner's wake, then a sea broke over her and she was gone.

"When you've finished star-gazing perhaps you'll tell me who you are," said the same brutal voice. Its owner, who towered over Clem, was all of six feet high. He had red hair, bristling red eyebrows, greenish eyes, a great hooked nose and a mouth like a slit. A regular slave driver by the look of him, and Clem's heart sank. "Carey is my name," he explained briefly. "I was out after mullet and got caught in last night's gale."

"Britisher?" inquired the other with a sneer.

"I am English," replied Clem curtly.

"Say sir when you speak to me," snarled the big man, aiming a blow at Clem's head. Clem ducked and sprang aside. His eyes were blazing.

Suddenly a girl ran in between them. A slip of a thing who looked about fourteen. She had great dark eyes, but even these were not so dark as her hair. "How can you be so unkind, Captain Coppin," she cried indignantly. "Can't you see that the boy is half dead."

Coppin scowled. "I guess he'll wish he was deader before I am done with him if he don't mend his manners. I only picked him up because I am short handed, and he'll have to do his share. But you can take him below and give him some grub. To-morrow I'll see what he's made of."

The girl led the way below and Clem followed. "It's awfully good of you to help me," he said. "But I say, what sort of ship is this?"

She shook her head. "A terrible ship," she said gravely, "but never mind now. You must have some food first, then I will tell you all I can."

The schooner was a big craft and several cabins opened off the saloon. The girl opened the door of one of these cabins. "Go in there," she said, "and I will get the steward to bring you some dry things and something to eat."

The steward, a little shrivelled Cockney, brought Clem a rough suit out of the slop chest, and a bowl of soup. The soup was greasy but hot and nourishing, and Clem felt fifty per cent. better when he had swallowed it. He had a good rub down before he changed his clothes and came out to find the girl waiting for him in the big cabin. "You'd better rest while you can," she told him, speaking good English, but with a foreign accent. "You will not get much rest after to-night."

"I can't rest until I know where I am and something about things," replied Clem.

The girl looked round cautiously. "Tell me who you are?" she asked in a low voice.

"Clem Carey is my name," said Clem frankly. "I came from England two years ago with my people to Florida. Dad's got some land, but it's scrub and no good, so we've been keeping ourselves by fishing. Yesterday I got caught in a storm, and you know the rest."

The girl looked at him as if she approved of him. "If you are English I feel that I can trust you," she said. "My name is Felizia Almeida. We are Spaniards, but I was born in the States. My father chartered this ship, the Wekiva, to hunt for a treasure." She stopped short as the steward came into the saloon. He passed through and went aft. "Oh, I'm frightened—frightened," whispered the girl.

"Never mind," said Clem consolingly. "I'll help you if I can."

"I feel you will, but you are only a boy, and there are so many of these dreadful men. Listen now; Coppin, the captain, has come to know about the treasure and he has stolen the directions from my father. I don't know what dad and I will do."

"Treasure," repeated Clem. "You must tell me more."

"It is on the island of Pedrogao. My father had the directions from the grandson of the man who hid the gold and pearls there more than a hundred years ago. We had to wait until now before we could get money enough to charter a ship, and now see what has happened."

"It sounds pretty bad," agreed Clem. "It looks as if Coppin will go straight to this island, bag the treasure and probably maroon you and your father somewhere."

"That is what father thinks, but there is one thing in our favour, the directions are written in Latin, and no one aboard except father can read them."

"That's all to the good," said Clem comfortingly but before he could say more the crooked little steward was heard coming back.

"We mustn't be seen talking," said Felizia. "Go forward and sleep. To-morrow, perhaps, we can do something."

She slipped away, and Clem, who was so done that he could hardly keep his eyes open, went forward to the fo'c'sle, found an empty bunk and, in spite of the violent motion of the schooner, was asleep in a minute.

A great roaring voice roused him. "Hey, there! turn out, you scum." Clem was up in a flash and lost not a moment in reaching the deck. Other men of the watch were running with him, and behind them Coppin and his bucko mate driving them with fists and boots. "Tail on to the halliards," shouted the mate, and Clem managed to get there one step ahead of the brute's toe. For his age—not yet fifteen—Clem was a big, strong lad and he put his weight into the job. It was a lovely morning after the storm, with a fresh westerly breeze, and sails were being set on the schooner.

He was breathless when at last the work was done, and he had a moment to look round. Close behind him was a short squarish man who looked less of a brute than the rest. "Is this the usual way they do things on this ship?" Clem asked in a low voice.

"Ay," whispered back the other. "She's sure a terrible ship, this, kid, and you'd have been better off if you'd stayed in that there boat of yours."

"But what do they do it for?" questioned Clem. "Surely the men would work without being beaten like this."

"Jest becos they're dirty bullies. Coppin's the worst, but Monkton the mate is nigh as bad. Sure as my name's Horner, some night he'll go over the side with a knife in his back."

"Now then, ain't ye got nothing better to do than stand and gawp like two old women," roared a voice, and Monkton was upon them. Clem dodged, but Horner was not so lucky, for a blow on the jaw sent him sprawling. Clem boiled with wrath, and the bucko mate got the shock of his life when the boy's fist caught him square on the end of his nose, hard enough to stagger him.

With a bellow like a mad bull he turned, and one blow of his great fist sent Clem, stunned, insensible, into the scuppers. Monkton leaped after him, but as he raised his boot for a kick that would have stoved Clem's ribs, suddenly Coppin was between them, "None of that, Mr. Mate. We're short-handed enough as it is and I ain't going to have you break that boy up. Wait till he comes round. Then you can rope-end him all you have a mind to. But you break up any more men and you'll hear from me. Here, one of you, chuck a bucket of water over the kid."

Clem came round to find Horner looking at him in a sort of dumb amazement. "What's the matter?" he asked hoarsely.

"Matter is as you're alive," replied Horner, "which you'd not have been if the old man hadn't have interfered. Monkton was sure going to kill you. But get up and get to work or they'll be arter us again."

A terrible ship Horner called the Wekiva, and that was what Clem found her during the next two days. But there were two things in his favour. One that the crew, having seen him stand up to the dreaded mate, treated him much better than they would otherwise have done, the other that Monkton himself, though he lashed Clem with his tongue and gave him every filthy job to do, did not hit him again. It almost seemed as if he was scared to do so.

Meantime the Wekiva sped southwards. Though old, her lines were those of a yacht, and she made wonderful speed.

Clem tried hard to get a word with Felizia, but this was out of the question. For whenever she was on deck, Coppin had his eye on her and her father. Almeida himself was a delicate looking man, and Clem watching him saw that he was almost worried to death and badly scared. "He knows what he is up against," thought Clem. "I wonder what is going to be the end of it all."

One evening when the schooner was running before a fair breeze, Clem saw a loom of land to the west. "What land is that?" he asked of Horner.

"South America, I reckon. That's all I knows."

"We've been making a lot of easting," said Clem. "I believe that's Trinidad, and that we are passing the mouth of the Orinoco."

"Likely you're right. Me, I don't know the names of them places. I never was in these waters before."

"Trinidad is British," said Clem, "but I am not sure we're so far south. That might be Martinique. However, we'll know soon, for Trinidad is flat and Martinique has a big volcano."

"How come you to know so much geography?" came a harsh voice, and Clem turned to find the skipper glaring down at him.

"I learnt it at school, sir," he answered quietly.

"Oh, so you are educated," grunted Coppin. He paused. "Come below," he ordered curtly, and Clem, wondering greatly followed.

Coppin took him to his own cabin, and seating himself at the table, fixed his cruel eyes on the boy. "Do you know languages?" he demanded suddenly.

Clem saw daylight, or thought he did. "Some of them," he answered modestly. "I can read French."

"What tongue's this?" Coppin took a sheet of paper from a locked drawer and pushed it across the table.

Clem inspected it. "It is Latin, sir," he answered. "I am a bit rusty on my Latin, but I think if I had time I could puzzle it out."

"Think you can read it?" said Coppin sharply. "Then sit down here and get to work. Here's paper and pencil."

Clem, of course, did not need to be told that the paper was the one which Coppin had stolen from the Almeidas, and his heart was beating rapidly as he ran his eyes through it. Although the paper was old and yellow, the writing was clear enough, and he soon saw that it would not be difficult to translate. The treasure, it appeared, was gold, in bars, and a parcel of valuable Panama pearls, and was hidden in a cave at the end of a deep cleft in the island of Pedrogao.

Some minutes passed, then Coppin spoke. "Have you got it?" he demanded.

Clem was thinking furiously. Now he sat back in his chair and faced the captain. "Yes, sir," he answered quietly, "I can read it. I have read it. But I won't read it aloud, except on conditions."

Coppin leaped to his feet. His face went dark with fury, the pupils of his eyes contracted to pin points. He snatched a pistol from his pocket and pointed it straight at Clem's head.

He pointed the pistol straight at Clem's head.

Clem was badly scared, but kept his head. "If you kill me, captain, the paper is useless. No one else aboard can read it except Mr. Almeida, and you've tried him already."

Coppin hesitated. "Well, what is it you want?" he asked harshly. "Speak out."

"I want a share," said Clem boldly.

"How much of a share?" sneered Coppin.

"The treasure is worth £50,000 or more, and I want £5000," said Clem.

"All right," replied Coppin, still sneering. "You shall have that. Now read it."

"No, sir," said Clem firmly. "I won't translate it until we reach the island."

Coppin stared, then gave a short bark of a laugh. "For a Britisher you've got more sense than some," he remarked. "All right, then, we'll wait till we reach the island." He paused, "But you try any games on me, my lad," he added fiercely, "and I'll make you wish you had never been born."

Days went on and still the schooner slipped southwards. Clem found the waiting fearfully trying. What he wanted above all things was a chance of speaking to Felizia, but he was constantly watched both by Coppin and Monkton. One night Coppin was at supper and Monkton was on deck. It was a very dark night, and had begun to rain, when suddenly a red glare showed up against the black sky on the starboard bow and some one sang out that it was a ship afire. Monkton cursed the speaker. "Ship! you something fool, that ain't no ship. Go and call the skipper."

Coppin came up, and as he and Monkton began to talk eagerly, Clem took his chance and ran aft. He met Felizia at the head of the stairs. "I was just coming to speak to you," he said quickly.

"So was I," answered Felizia, "They say there is a light in sight."

"Yes, over there."

"It is the island. That is a volcano on Pedrogao. But—but now you have joined them—" she wrung her hands hopelessly.

"I haven't," Clem answered indignantly. "I only pretended."

"But you read the paper."

"I read it all right, but I didn't tell them. I told Coppin I wouldn't tell him what was in it until we reached the island. I pretended I wanted a share. You understand?"

"Yes," she answered breathlessly, "but now what can you do? As soon as Coppin knows, he will take the treasure and leave us on that dreadful island. Very likely he'll kill us."

"No, he won't. Listen. I have a plan. When we get to the island, Coppin will take me and Monkton with him in the boat. From the map, that deep cleft where the treasure is hidden is a nasty place. My notion is to get them to row in there and wait for me to fetch the pearls. But as soon as I get ashore I'm going to sink the boat with a big rock. Oh, it's a bit of a risk, I know, for they may shoot me, but they won't suspect me of trying any such trick, because they think I want a share. Now listen. While we're away you get hold of Horner. He's white and there are two or three others who'll help him. Horner will come off in another boat and I will swim out with the pearls and meet him. Then we leave Coppin and his gang on the island and clear out with the schooner."

"It—it's a terrible risk," gasped Felizia.

"Not so bad. I swim pretty well," said Clem, smiling. "Now I must go, but keep up your spirits, and all will come right."

"I'll try," promised Felizia. "And—and thank you a thousand times."

The red light was that of the volcano, and next morning the Wekiva lay off the island of Pedrogao. It was a gloomy looking place. Gaunt black rocks rose grimly from the jade green sea, and in the centre was a blunt, cone-shaped mountain from which volumes of smoke belched thick and dark, driving away down wind.

"'Orridest-looking place I ever seed," Clem heard the Cockney steward remark, and he thoroughly agreed with him.

Coppin was gazing at the island through his glasses and scowling as he did so. He shut them with a snap. "Get the small boat over," he ordered. Clem was surprised, for he had expected the big cutter to be lowered. His surprise changed to dismay when he saw Monkton coming up from below with Felizia and her father. There was worse to come, for the next thing that happened was that Coppin ordered Horner, and two others of the more decent men, into the boat. "You'll go ashore with them, Mr. Almeida," he said smoothly, but with a wicked grin. "We're following later."

Clem saw Felizia cast a despairing glance at him, but he could do nothing, for Coppin was watching with his cynical grin.

Coppin beckoned to Clem. "Are you ready to read that paper?" he asked curtly.

"Yes, but what about my share?"

Coppin's grin was worse than his scowl as he took a pad of paper from his pocket, scribbled a few words on it and handed it to Clem. "That's for you," he said. "Now where's the stuff hid?"

"In a sea cave at the end of a cleft half a mile from the south-east point of the island. The treasure is on a ledge about thirty yards inside the cave."

Coppin glared at Clem. "Is that the truth?"

"Of course it's the truth. You don't think I want it all, do you?"

Coppin stared and sniggered, and Clem saw he was convinced. Yet for all his bold face Clem was almost at his wits' end. All his plans had gone wrong, for now, even if he succeeded in sinking Coppin's boat, he saw no chance of getting away with the treasure. The chances were that Coppin and Monkton would easily swim ashore and grab the other boat before he could get Felizia and her father away in it. But there was no time to think, for Coppin and Monkton were going over the side into the cutter.

"That's the creek," said Coppin, pointing. "Pull, you swine."

A long swell was running and breaking in great spouts of foam on the black cliffs. The air was hot and sticky. Monkton was watching the volcano. "She's smoking a lot," he said, scowling.

"She's always smoking," said Coppin.

"Ay, but there's more than there was an hour ago."

"We'll be away before there's any trouble," said Coppin with his cruel grin; and then no more was said until the boat came opposite a narrow inlet which ran curving deep into the mouth of the island. The great swells charging inwards in smooth, green hills, broke in roaring foam at the curve. "A regular death trap," growled Monkton. "How in thunder are we going to get in there?"

Coppin pointed to a strip of beach to the left. "We'll land there," he said. "Likely there's some way round."

A minute later the boat grounded on the shingle and two men jumped out to pull her up. Suddenly the boat rocked violently, and at the same time the two men staggered and one fell.

"What are you playing at?" roared Coppin, springing out. But as his feet reached the beach they seemed to give under him, and he too fell. "Who tripped me?" he demanded fiercely.

"No one tripped you," snapped Monkton. "It's an earthquake. Here, let's get out of this."

"Get out of it," snarled Coppin. "Have you gone yellow like the rest?"

"No," sulkily, "but if the volcano opens up, gold won't help us."

"You make me tired," snorted Coppin. "Here, get ashore all of you, and get the ropes out. We're going to climb over that spur and take a look at the inner end of the gulley."

If scared of the volcano, the men were worse scared of Coppin. They obeyed, and Coppin, with Clem and Monkton, started to climb. It was tough going, but at last they gained the summit, and were able to look down into the inner end of the inlet. A triangle of heaving green showed beneath, and the rollers, sweeping across it, disappeared beneath an overhanging ledge, breaking out of sight with a dull roar. "It's the cave right enough," said Coppin. "We can't get in yet, but when the tide's down it will be all right. Get back to the beach. We'll wait there."

Back on the beach Coppin ordered a fire to be made and food cooked. There were constant tremors of earthquake, but Coppin himself was so set on the treasure that he thought of nothing else. The men, however, as well as Monkton, were looking very blue. Two hours passed, the quakes became more frequent, and an ominous roaring told that the crater itself was in action. Clem was very worried about Felizia. His only comfort was that Horner was there to look after her. The men were getting more and more terrified. Suddenly there was a worse quake than any yet and a huge rock dislodged from above and fell with a thunderous splash into the inlet. Monkton sprang up. "I'm not staying any longer," he cried. "We'll all be dead if we don't clear out."

Coppin pulled out a pistol. "You'll be dead anyway if you talk like that. I've not come all this way to go back empty-handed. Get into the boat," he ordered, "we're going in." At pistol point he drove the terrified ruffians into the boat, and he himself took the tiller. "Give way," he ordered, and the cutter, lifting on a great roller, went rushing into the gap. Jagged rocks rose on every side, but, tiller in hand, Coppin swung the boat away from each. Brute as he was, his nerve and seamanship thrilled Clem.

The inlet narrowed. The shadow of the black rocks lay dark across the boat. The roar of the breaking surges was deafening. Clem was too excited to be afraid, yet he did not believe that the boat could live to round the curve. She dropped into a trough and the water broke over and half filled her, then in the nick of time another wave lifted her and sent her soaring.

"Pull," roared Coppin, and the oars beat the water desperately. Then quite suddenly the curve was passed and the boat riding in safety in the inner end of the inlet. "There's the cave," shouted Coppin. "In with you; sharp about it."

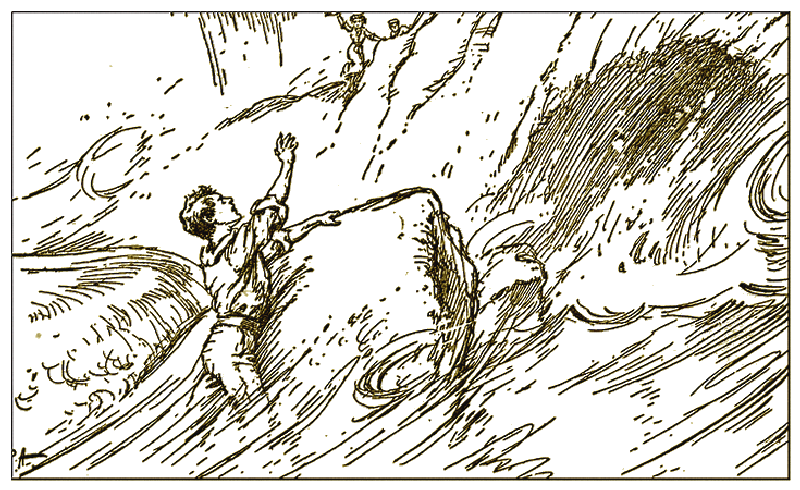

As he spoke came a roar that drowned the thunder of the surf, and Clem, looking up, saw a huge avalanche of rock sliding down the cliff face directly above the mouth of the cavern. Quick as a flash he was on his feet and, leaping over the side of the boat, dived deep into the face of an oncoming breaker. Down he went, down until his lungs were almost bursting before at last he dared to let himself rise again. Reaching the surface he dashed the water from his eyes, and looked round. The sea, dark and discoloured, was boiling and seething, and between him and the cave-mouth a mass of rubble rose above the surface. Of the boat or of its occupants there was not a sign.

Horrified as he was, it would be absurd to say that Clem felt any sorrow. Rather it was relief that Coppin and Monkton were out of the way. He climbed on to the new-made islet and took breath. At any minute a new convulsion might bring the whole cliff down on him, and his first instinct was to swim for the open sea. Next moment he realised that this was impossible, for the strongest swimmer on earth could never have forced his way through the great rollers which crashed into the gulley. Clem's lips tightened. "Better if I'd stayed in the boat," he said grimly. He looked up, wondering if there was any possibility of climbing the cliff, and suddenly saw a white something fluttering high above It was a handkerchief, and Felizia stood on the cliff edge waving to him. "But how can she help me?" he asked himself. Then as he watched her he understood, for a coil of rope came swinging down the cliffside. Clem was on the point of plunging in to swim across to the rope when he stopped short. The treasure! He had clean forgotten the treasure. He cupped his hands over his mouth and shouted: "The pearls! I'm going after the pearls." He pointed to the cave mouth.

Felizia stood on the cliff edge waving to him.

"No—no, don't wait," came Felizia's voice shrilly. "It's not safe."

"It's worth the risk," he shouted back, and next moment was swinging hard for the mouth of the cave.

For the moment the earth movement had ceased, but there was still a deep rumbling from somewhere in the heart of the island and Clem fully realised the fearful risk he was taking, for at any moment a fresh shock might bring the roof down on him. Within the cave the light, though dim, was strong enough to show him his surroundings. He struck to the left. The directions were clear in his mind as if he had the paper before him. He saw the ledge, reached it, and catching a projecting spur, dragged himself up. As he did so, he felt the rock quiver like the lid of a boiling pot.

Panic seized him and he was on the point of dropping back and swimming for dear life out of the sea cave when he caught sight of something in the distance which shone with a dull yellow gleam. Forgetting his fears he climbed on to the ledge, and, crawling along it, reached the spot.

"Gold," he cried, as his fingers closed on a great bar of the precious metal. There were others beyond, ten in all. He tried to lift one but could barely move it. "No good," he groaned; "riches for us all, and I can't get away with a pound of it."

The rock was quivering again, and stones, breaking from the roof above, dropped heavily into the deep water. There was nothing for it but to clear out, but as Clem turned to dive into the water he noticed a small, dark object lying between two of the bars. He picked it up. It was a small bag of raw hide, so old that the leather was hard. He shook it and something rattled inside. "The pearls," he gasped, then came a fresh quake. Thrusting the bag into a pocket he sprang into the sea and swam hard for the entrance.

The rope still dangled from above and Felizia waved frantically. "Hurry," she cried, and Clem realised that the need for haste was urgent. He fastened the rope round his waist and was hauled rapidly up.

"I've got the pearls," he panted as he came over the edge of the cliff.

"Pearls ain't worth lives," answered Horner. "Look at that." Clem saw a great flood of lava rolling in a white hot river down towards the sea.

"We've got to cross in front of that to reach the boat," said Horner grimly.

"We'll do it," declared Clem. "Come on."

The ground was fearful and the going made worse by constant earthquake shocks, while from above the smoking torrent of lava came crashing over the ledges. Felizia's father kept stumbling, but Horner and Peterson, the other man, dragged him along between them. As they crossed in front of the lava flow it was so close that its heat scorched their faces as they rushed by.

"Hooray," cried Clem, "we're saved."

"Best not crow too soon," said Horner pointing out to sea.

In spite of the heat Clem felt cold chills running down his spine, and his legs went weak under him. For a wave, a huge wall of water, was rolling in upon the island. They saw the schooner swing high on its mighty crest, then with a frightful crash the wave broke upon the island, shaking the solid cliffs.

"Boy, I reckon this is the finish," said Horner in Clem's ear.

"The schooner is still afloat," answered Clem.

"Ay, but she ain't got another boat."

Clem's heart was in his boots, for what Horner said was true, and now, since the wave must have smashed their own boat to atoms, there was no way of getting off the island where, even if not killed by the fury of the eruption, they were doomed to die of hunger and thirst. But Clem would not give up. "There may be wreckage left to build a raft," he said. "Wait while I go to the beach and see." But when Clem reached the beach he found it bare as the palm of his hand, scraped to bed-rock by the fearful force of the earthquake wave. Numb with despair, he was staring out to the schooner when a wild shout from above made him turn. "Say Carey, it's all right," roared Horner. "The boat's here."

"You're crazy," retorted Clem.

"Not by a long sight. By some miracle the boat's caught up here and still as sound as a bell."

Hardly able to believe his ears, Clem scrambled back, and sure enough there was the boat cradled between two rocks and, as Horner had said, quite unharmed. Even the oars were still in her. Between them they got her down, and just as the lava flood came pouring over the rim of the cliffs and hissing into the sea, the five pushed off and pulled away towards the schooner. Once aboard, they got the engine going, and before nightfall the red beacon of the island volcano had faded on the southern horizon.

THAT night Clem, with Felizia and her father, talked together in the saloon. "I am heading for Georgetown, Demerara," said Mr. Almeida. "The engineer tells me there's oil enough to take us that far, and once in a British port we should be all right."

"What about the men?" said Clem.

"We shall have no trouble," was the answer, "for I am promising them five hundred dollars apiece in addition to their wages, and Horner and Peterson are to have a thousand each."

"That's a lot," said Clem.

"One pearl will sell for enough to do all that," he said. "And there are forty large ones, besides more than a hundred smaller."

Clem whistled softly. "Why, it's a fortune," he said.

Mr. Almeida nodded. "Yes, my boy—fortunes for all three of us."

"For all three!" repeated Clem. "I have got nothing to do with it."

"You had everything to do with it, for without you Felizia and I should have lost not only the treasure but also our lives. It is her wish as well as mine that you take half the pearls."

Clem got very red. "I couldn't," he declared.

Felizia spoke. "You can and you will, Clem. Remember that you have to buy a new boat as well as a new home for your people."

Clem gasped. "Why, I can take them all back to England," he exclaimed.

Felizia laughed merrily. "Yes, and in your own steam yacht if you like to buy one, Clem."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.