RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Before he could even turn the bank was alive with Indians.

NO one but a mad Englishman would dream of walking the blazing streets of Manaos at midday, and even Boyd Carling was thinking that he had better seek shelter if he did not want his brain to start boiling. He was heading back towards the river when the baking silence was broken by the clearest, sweetest whistle he had ever heard, and out of a side street came a ragged-looking youngster of about fifteen, pouring out "Annie Laurie" as if he had a flute inside him.

At first sight most people would have taken the boy for one of the half-breeds, or mestizos, with whom the place swarms, but Carling spotted his blue eyes and curly red hair, and knew better.

"Hi!" he called.

The boy stopped whistling. "Hulloa!" he answered.

"You're English?" said Carling, a puzzled line on his forehead.

"You bet," replied the boy. "Anything I can do for you?"

Carling felt a little awkward.

"N-no—unless you'd like to tell me how you learnt to whistle like that."

"I never learnt. It just came," smiled the youngster. "And I do it to keep my spirits up in this hole of a place."

"It is a hole," agreed Carling. "You live here?"

"Yes, worse luck!" Carling's friendly interest seemed to encourage him. "But I'm only waiting till I can get on up the river. I'd start to-day if I had the cash."

Somehow Carling found himself extraordinarily interested.

"Do you mean to say you're all alone here?" he asked.

The boy nodded.

"How do you make a living?"

"Odd jobs," replied the boy, with a shrug. "Doing anything now?"

"Nothing."

Carling looked at him a moment.

"My boat's over there," he said, pointing to the wharf. "Come aboard and have a yarn."

"I'd love to," replied the boy, frankly.

Carling's boat, the Caiman, was a broad-beamed, flat-bottomed stern-wheeler about seventy feet long. The minute the boy set eyes on her, he pulled up short.

"You're Mr. Carling?" he said, sharply.

"Yes; I'm Carling."

"Carling the naturalist?"

"Collector," corrected Carling, with a smile. "Of course, I've got to be a bit of a naturalist to do my job."

"And you're going up the river?"

"Yes, I leave to-day."

"Take me with you," begged the boy. "Take me along. I can cook, and make myself useful lots of ways. I don't want any wages. I'll do any kind of work if you'll give me a job aboard."

Carling paused a moment. "Come aboard," he said, "and we'll talk it over."

The boy went across the gang-plank as if treading on air. Carling took him into the big, airy cabin, and gave him a chair and a cool drink.

"Now," he said, "let's hear all about it."

The youngster, who gave his name as Dick Severn, spun a yarn which made even Carling open his eyes.

Richard Severn, his father, had, it seemed, invested every penny in a Brazilian rubber company. The company had gone wrong, and he himself had gone out to see about things, leaving Dick in charge of an uncle. Six months later the uncle had gone bankrupt and shot himself, leaving the boy absolutely stranded. He had no other near relatives, and there was no one to look after him.

Dick at once made up his mind to follow his father, whose last letter was dated from Manaos, and with the few pounds he had left took a steerage passage on a Booth boat.

"I got to Manaos four months ago," he went on. "But there was no sign of dad. It seems the company had gone bust altogether, and he had heard of some wonderful new ground up the Yapura River, and hurried off to look at it. That's seven months ago, and since then no one has heard a word from him. I've been just crazy to go after him, but I hadn't a red. Now you know why I'm so keen on a job with you."

"I certainly do," replied Carling. "All right, my lad, I'll give you a show."

Dick's face lit lip. "That's awfully good of you," he declared, fervently.

"Don't thank me yet," said Carling. "I'm on a special job, and it's not going to be any beanfeast, I can tell you. But you'll learn all about that later. Now go and fetch your kit. We're off in an hour."

Manaos is as far from the sea as Paris is from Petrograd. Yet even here the Amazon is big enough to float a ten-thousand ton liner. As for a light craft like the Caiman, there is enough water to the west of Manaos in which to steam for half a lifetime.

Leaving the Rio Negro, and turning up the main stream of the Amazon, the Caiman drove on day after day against the sluggish current. At night she was anchored near the bank, and sometimes Carling spent a day ashore with traps or nets and collected birds or beasts. Dick saw that he was particularly keen on lizards and one glass case after another was filled with skinks, tejus, swifts, and iguanas. They were of all colours—green, yellow, black, brown, and blue. Some had queer crests and combs, others huge scarlet pouches under their throats. Some were scary, some were savage. The big black iguanas, which ran to five feet in length, were really dangerous if carelessly handled. They bit fiercely, and their three-inch claws would rip a man's arm or leg like so many knives.

It was when he was feeding one of the iguanas that Dick made a discovery. The brute was mad angry, and kept rushing at the bars of the cage. At last Dick hauled off and started whistling. The lizard stopped its antics at once, and lay quivering.

Dick whistled very low and softly, and the tense creature slowly relaxed. Gradually he came nearer and nearer, and began waving his hands to and fro. Carling, coming up a little later, found, to his amazement, that the ugly tempered brute was actually taking bits of meat from the boy's hands.

"That's good," was all he said at the time, but that night he called Dick into his own cabin.

"I thought you had it in you, Dick," he said; "the taming instinct, I mean. Now that I've seen how you handled that iguana I'm going to let you into the secret. Have you ever heard of the iguanodon?"

"Yes," said Dick, abruptly. "Sort of ancestor of the iguana, wasn't it? Whacking big brute, but extinct about a million years ago."

"That's what the books say; but I'm not so sure that it is extinct. On my last trip I met a rubber collector named Bradley who'd been up in the Macaya country. He had a story that the iguanodon still exists between there and the Yapura. Then Maqui, that Indian I have with me, has told me that the Corijas keep one as a sort of tribal deity. He vows he has seen the brute, and what makes me believe it is that he describes the queer hook on its forepaws which we know the real iguanodon possessed. Anyhow that's what I'm after. Are you game to come with me?"

"Rather!" Dick answered, emphatically.

"It's not going to be easy," warned Carling. "These Corijas have none too good a reputation."

Dick laughed. "I told you I wasn't hunting a soft job," he answered. "Besides, my father is somewhere up the Yapura."

Ten days more they steamed up the broad river between lines of endless forest. Then one night Carling ran the Caiman into the mouth of a small tributary, and tied up.

"We start to-morrow, Dick," he announced. "Get everything ready to-night."

They were off at dawn, Maqui, Carling, and Dick. They went by canoe up the little tributary, the Indian acting as guide. Hitherto they had travelled in comfort, but now they had to rough it in earnest. The creek was not a bit like the big Yapura. It was narrow, winding, and often barred by fallen trees, which had to be cut through. The logs were full of ants, great red things whose bite was like fire.

At night they had to camp ashore and burn smudges the whole time to keep off the hordes of mosquitoes. Panthers screamed like lost souls in the depths of the forest, and snakes were far too plentiful to be pleasant. Dick had a narrow escape from a ten-foot bushmaster which came at him like a tiger as he was cutting wood, and would have killed him if Carling had not blown its ugly head off with a load of buckshot.

ON the fourth day Maqui was clearly uneasy, and late that

evening they heard a new sound from the forest. It was the most

extraordinary droning roar which went on and on for minutes at a

time. Dick saw that Maqui was literally shivering with

fright.

"It's a bull roarer, Dick," said Carling, rather gravely. "A war-call, I'm afraid. Maqui says so, at any rate, and vows the beggars are stirred up about something. He wants to go back. What do you think, lad? Shall we?"

"I don't see what use it would be to go back," Dick answered. "If they're really after us they can get us as easily one way as the other."

"That's what I think," Carling agreed.

Nothing happened that night, and after an early breakfast they pushed on. About ten they came to a tree which blocked the creek from bank to bank. Dick had just got to work on it with an axe when he heard a yell from Maqui. Before he could even turn, the bank was alive with Indians.

They were short, thick-set fellows, very dark in colour, and armed with knives and long blowpipes. They had come without a sound, and they stood, silent and threatening, their glittering eyes fixed on the white men.

Dick made a jump for his rifle, but Carling checked him.

"No use, Dick. They've got the drop on us, and those blowpipe darts are more deadly than bullets. Don't know whether I can make 'em understand, but I'll try."

They seemed to understand all right, but Dick, watching Carling's face, did not get much comfort from it. The Indian chief, who wore a wonderful head-dress of green and scarlet macaw feathers, answered.

Carling shrugged his shoulders.

"We've got to go with them, Dick. I don't know what the game is, but, as I said before, they've got the drop on us."

He stepped out quietly on the log, and Dick followed. Maqui, who was in such a fright that he could hardly walk, staggered after. The Corijas pulled up the canoe on the bank, unloaded it, and marched their prisoners away up a narrow trail through the forest.

The ground rose, but the trees were too thick to see where they were going. The steamy heat was awful, and even the brown bodies of the Indians shone with sweat. They went on for hours, and Dick was ready to drop when at last they came out into a sort of cup in the hills, a savage-looking spot ringed by tall reddish cliffs, and with steep mountains barring the northern horizon. The floor of this cup was level, and all around it, nestling under the cliffs, were scores of beehive-shaped huts.

In the centre grew a clump of black, gloomy-looking bush, with some huge trees rising from it. Out of the huts peered women and children by the dozen, but they were as quiet as so many mice. The silence that brooded over the whole place was simply uncanny.

A word from the chief, and the white men were marched to an empty hut, and placed there under guard. Maqui was taken off somewhere else, and they were left alone with their reflections.

"What's the game?" asked Dick of Carling.

"Wish I knew, lad. My own impression is that it's one of their religious festivals. They're a sight too quiet to suit me."

The words were hardly out of his mouth before the brooding silence was broken by a hissing like that from a hundred snakes. The sound came from the black clump in the centre of the hollow.

The two stared at each other.

"What do you think that is?" asked Dick, slowly.

"I can't tell for certain, Dick," replied Carling, "but at a guess I'd say it was the tribal deity, the big lizard."

"Must be a cheerful sort of beast," said Dick. "It can give points to a steam-whistle."

The sound ceased, the hot silence fell again, and the prisoners, tired with their long tramp, lay back and rested. Dick slept, but Carling sat with his eyes fixed on that odd-looking clump of bush. His face was set in anxious lines.

As the blazing heat began to give way to the cool of evening, stewed meat was brought to them in wooden bowls. What it was they had no idea, but they were too hungry to be critical. Before they had finished eating, the open space in front began to fill with Indians. They moved as quietly as so many ghosts, yet there was a sort of expectant air about them.

The chief, in his gorgeous head-dress, appeared at the door of the hut, and beckoned them out. For all the expression on his chocolate-coloured face it might have been carved out of wood.

"What do you want of us?" demanded Carling, in the native language.

"You will see soon," was the only reply he got.

"Come on, Dick," said Carling, and Dick stepped out, with his head as high as his spirits were low.

Heavily guarded, they were marched across to the central grove. The whole tribe followed, but not one so much as opened his lips.

A path, narrow but well beaten, led through the trees. The branches, tangled with great rope-like lianas, made a thick roof overhead, so that underneath all was in the deepest gloom.

Quite suddenly they were in the light again, and on the edge of a large, oval-shaped pit. It was perhaps a hundred feet across, and the perpendicular sides were of the same reddish rock as the cliffs above.

At one end of the pit was a flight of steps cut in the living rock, and these were protected by a strong stockade built of timber, with a gate at the head of the steps. From the pit itself rose an unpleasant musky odour.

The bottom of the pit was in deep shadow, and for the moment the captives could see nothing. Then suddenly there rose from the depths the same hideous hissing which they had heard before, but now intensified a hundredfold by their nearness.

Dick saw it first, and gasped. Heavens, but the deity of the Corijas was a fearsome thing! Imagine a twenty-foot alligator with a body the hue of jet, and a row of spear-shaped spines running all the way down the crest of its back. Colour these spines a livid green, and give the monster under its throat a large pouch of a dull red colour. Then you may have some notion of the beast that Dick saw crouching in the depths below.

As Dick watched, the creature rose suddenly to an upright position, the pouch on its throat swelled and turned vivid scarlet, and from its open mouth came a hiss like a jet from the escape-valve of a steamer.

"Pretty creature!" he remarked, turning to Carling.

Carling never even heard him. He was staring at the monster as if fascinated.

"The iguanodon!" he muttered. "The real thing!" And Dick saw that he had absolutely forgotten his surroundings, the danger in which they stood, everything, in fact, except that he was looking at a creature which the scientific world pronounced became extinct a million years ago.

Carling stepped forward to the edge of the pit. The iguanodon dashed forward, running on its hind legs. Its curved claws, which were fully two feet in length, scrabbled furiously against the rock.

A guard thrust Carling roughly back. Carling's face flamed, but he managed to restrain himself.

There came a stir at the far end of the pit. Dick gasped as he saw another white man being dragged to the gate, which was now opened.

The white man was thin and his face haggard. His clothes were torn and ragged, but Dick recognised him in an instant.

Another white man being dragged to the

gate. Dick recognised him in an instant.

"Father!" he shouted, and leaped forward.

The guards sprang at him. He ducked under an outstretched arm, tripped a second man, and, flashing through the crowd, had almost reached Mr. Severn before he was forcibly stopped.

There was an angry murmur among the Indians. Then Carling's voice rang out. He spoke in the Indian language.

"Chief, they are father and son. Let them meet."

"They will meet soon enough," said the chief, with a sneer, and pointed to the bottom of the pit.

Carling understood, but before he could frame an answer, Dick Severn broke in.

"Mr. Carling, tell them I will go down first. Yes, I mean it. I believe I can handle the brute. Anyhow, it's our only chance."

Carling hesitated. He knew Dick's power with the lizards, but this—this was different. The odds were a million to one against the boy.

And yet, as Dick had said, it was the only chance. Carling turned to the chief, and spoke briefly and forcibly.

A flicker of amusement showed on the Indian's wooden face, and his voice had the same sneer as he answered.

Carling looked across at Dick. He steadied himself with an effort.

"All right, Dick. He agrees. And I've made him swear that he'll let the lot of us go if you come out of the pit alive."

"That's all right," replied Dick. "And, I say, Mr. Carling, if the brute does get me, just see if you can't take that swine of a chief with you into the pit."

"You bet I will," said Carling, grimly.

Dick was released, and walked straight towards the gate at the head of the steps. A guard offered him a spear. He shook his head, and passed on.

The Indians stood like so many statues. Carling's heart thumped liked a hammer.

The monster had subsided again. It lay flat about the middle of the pit. It did not even seem to see Dick.

Dick went down the steps, walking very slowly and quietly. He got about half-way, then stopped, and began to whistle. The notes rose with astonishing sweetness and clearness above the sultry silence which brooded over the strange scene.

Carling turned his eyes upon the great lizard. The creature was lying perfectly quiet.

Step by step Dick went downward, whistling as he went. He reached the bottom, and still the lizard did not move. Dick's whistling dropped a tone. It became a gentle, flute-like crooning, slow and with a soft, monotonous refrain.

On he went steadily, moving his feet with the utmost deliberation, and making straight for the monstrosity in the centre of the pit.

Carling could hardly breathe. Almost he began to believe that the miracle was possible.

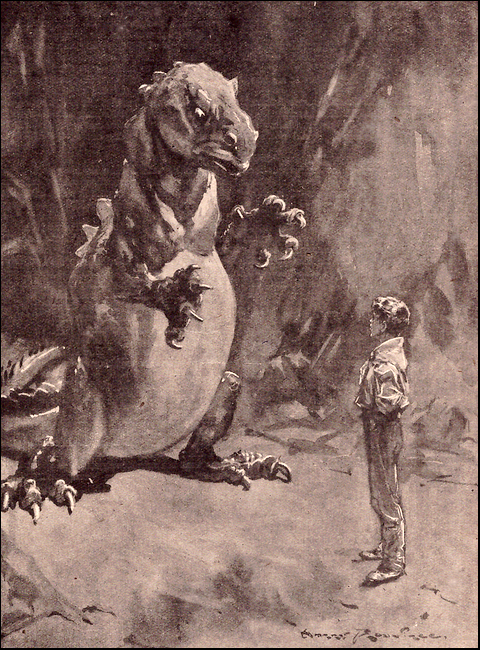

Dick was within a dozen paces of the lizard when up shot the brute to the full of its towering height, and whirled upon him like lightning.

Dick was within a dozen paces of the lizard when up shot the

brute to the full of its towering height, and whirled upon him.

Dick never moved. Motionless he stood as the Indian chief himself, and the only sign of life was the thread of sweet sound which still proceeded from his lips.

Carling jerked forward. Dick, of course, was done. There was nothing left but vengeance.

Then—then—were his eyes playing him tricks? The iguanodon was flat again. Its alligator-like head was pressed against Dick's knees, and he—he was scratching its scaly crown with the knuckles of his right hand.

A sigh that was like the breath of wind rose from the lips of the watching hundreds as Dick, still whistling, looked up and spoke to Carling.

"Tell them to bring some food," he said.

Carling spoke to the chief and there was a new respect in the latter's voice as he ordered a chicken to be brought. It was handed down into the pit, and the Indians, crowding round, silently watched the amazing sight of their tribal terror eating like a dog out of the white boy's hands.

THE chief was a man of his word. He let all four prisoners go. In any case not one of the tribe would have touched them after Dick's exploit. In fact, they would not so much as go near him.

The little party left the village at once, and made off towards the creek and the canoe. They could not travel as fast as they would have liked, for Dick's father was suffering from the results of three months' imprisonment in the village, and was pretty shaky in consequence.

Dick was the first to break the silence.

"Pity we couldn't have brought the old lizard along," he said, regretfully. "I believe he'd have followed me all right."

"'Pon my sam, I believe he would," replied Carling, with a smile. "But I'm afraid it would have been rather tight quarters in the canoe, eh, Dick?"

"I hadn't thought of that," returned Dick, rather ruefully. "But we might have made him swim."

There was a pause. Then Carling spoke again.

"Dick, I don't suppose there's a man in South America who is as keen on that beast as I am; but I'll tell you straight, I wouldn't have that ten minutes again on the edge of that pit, no—not for a dozen iguanodons."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.