RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

"The Little Admiral," William Collins, London, 1930

"The Little Admiral," William Collins, London, 1930

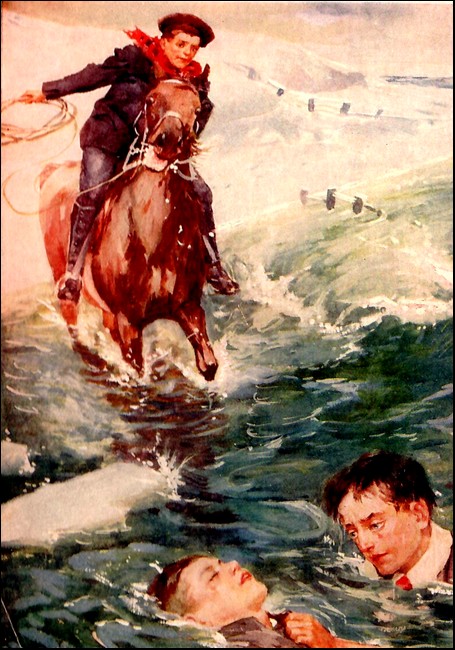

Frontispiece.

"Catch it, Mr. Robrtz—catch it!"

"BLAKE! Blake!"

Blake Hawtrey, coming up the steep coombe side with a couple of trapped rabbits, heard his mother calling, and recognised an unusual excitement in her tone.

He shouted in answer, and saw her hurrying down to the garden gate. A very pretty picture she made, for at thirty-seven Mrs. Hawtrey was still a beautiful woman, and though her dress was of the plainest, her figure was slight and graceful. Her fair hair shone in the winter sun, and behind her was the cottage with its thatched roof and white-washed walls covered with dark green ivy.

"Blake, a letter from his lordship at last!" she said.

Blake doffed his cap. He treated his mother with a courtesy which was not yet old-fashioned in the year of our Lord 1797.

"He has not hurried in his reply, madam," he answered, in a slightly sarcastic tone. "And what is my uncle pleased to say?"

"He writes kindly, Blake. He wishes to see you. He promises a commission in His Majesty's Navy."

Young Hawtrey's tanned face flushed slightly.

"Ah, that is news worth hearing," he exclaimed.

"You are to go to him at once," continued his mother. "He is staying at the seaport of Plymouth, and desires that you should come to him there. He has sent a bank draft for your journey."

Suddenly her face changed. Tears filled her eyes.

"My boy!" she cried, "my boy, you will be leaving me—and when shall I see you again?"

Blake put his strong young arm around her.

"That cannot be helped, madam, dear," he said softly. "And do not think of the parting. Think of the change in our fortunes. Think of the time when I shall come home, with my pockets full of prize money, and able to give you the comforts which you have so long been without."

"I care not for luxuries, Blake, my dear. I have been very happy with you in this humble place. It will be lonely indeed in the days to come."

"I leave you in good hands, madam," said the boy. "Mrs. Judd will care for you. And Amos Judd—"

"Amos will not stay here. He vows he will go with you, my son. He will enlist himself upon the same ship. No, do not contradict me, Blake! I shall be happier to feel that he is beside you. Perchance his great strength will be of use to you."

"He is strong enough, indeed," said Blake, with a smile. "Ah, here he comes."

As he spoke, a boy came up the hill, bearing on his shoulder a log of wood that few men could have carried. He had a shock of red hair, and a pair of keen blue eyes. Though not seventeen, Amos Judd stood already six feet and an inch, and was famous through the quiet Devon country-side for his feats of strength.

"Mistress shall not lack for fuel this winter, Master Blake," he said. "When us are a shipboard, she shall be fine and warm, I warrant."

"So you have made up your mind to come with me, Amos?" said Blake with a smile.

"I reckon so," Amos answered sturdily. "Two's company, master, even if one's on the quarter-deck and t'other in the forecastle."

So it was arranged, and two days later the pair left the pretty cottage at Withycombe and started for Okehampton, where they were to get the coach for Tavistock and Plymouth.

Blake's heart was sore at parting from his mother, yet he was comforted by the feeling that she was in good hands. Amos's father and Mrs. Judd would look after her right well, and see that she lacked for nothing. And her income, though but a slender widow's pension, was at any rate sure.

Both the travellers were warmly but roughly dressed. Blake was in a suit of brown homespun, with worsted stockings and square heavy-soled shoes. They carried their small wardrobes on their backs in neatly-strapped bundles. But Blake had guineas in his pocket, and at Plymouth would buy a finer suit in which to present himself to his uncle.

Lord Chenton was his mother's half-brother. He had quarrelled with her about her marriage, for Captain Hawtrey, though of good birth, had little money and no prospects. For years he had never even written to her. It was only within the past few months that he had done so, and that—as he let her know—was because his brother's son, Ralph Crosier, had disappointed him. Ralph had become a gambler, and had ended in being accused of cheating at White's. So my lord had cast him off, and was minded to give his younger nephew a chance.

It was late in the afternoon when the two travellers reached Plymouth and were set down at the Feathers Hotel in the Barbican. Plymouth, in those days, was but a small place, and Devonport did not exist. Yet small as it was, it seemed large to Blake and Amos, and they looked in wonder at the Cattewater crammed with shipping, and at the stately men-of-war lying at anchor under shelter of Drake's Island.

"To think we shall be aboard one of those in a few days," exclaimed Blake. "And now, Amos, before we do aught else, we will find our way to a clothier's and get fresh suits. I would not wish to appear before my uncle in these rough things that I am wearing."

They went into the hotel, and Blake inquired of the boots the name and address of the best clothing shop.

A man who was lounging by the bar turned and glanced at Blake. Then he stepped up to him.

"I heard your question, young sir, and I may be able to answer it better than the boots. I should, were I you, go to Adams's shop in Treswell Street."

Blake looked quickly at the man. He was about thirty, smartly got up, and his voice and manner both seemed to warrant him a man of breeding. True, he had a somewhat dissipated appearance, but that was so common in those days that Blake thought little of it.

"I am obliged to you, sir. In Treswell Street, you say?"

"Yes, and as it happens, I am going that way. I shall be happy to guide you."

Blake thanked him again, and presently the three were threading their way through the narrow, dirty streets of old Plymouth. The sun was down now, and a sea mist blowing up. The air felt chill, and most people seemed to have gone indoors.

Blake was glad of a guide. He would never have found his way through such a maze of alleys.

They had turned into a street which seemed full of ships' chandlers shops. It reeked of tar and tallow. At the lower end they glimpsed dark water through the fog.

Suddenly came the heavy measured tramp of a strong body of men. A loafer, looking in at a shop window near by, started violently, then ran.

"The Press!" he shouted, as he passed the boys.

"The Press-gang, does he mean?" asked Blake sharply.

"Yes, but they will not meddle with you while you are in my company," replied their guide, swelling his chest. "Even they know a Greville when they see one."

Before Blake could speak again, round the corner came at least a score of men-of-war's men. Great, broad-chested fellows in striped slops and glazed hats, with their pig-tails hanging like ropes down their backs.

An officer led them, a stout, black-jowled man, with a hard face and a scar on his forehead. His eyes gleamed as they fell upon the two boys.

"Ha, here are a couple of likely lads!" he cried. "They'll do to serve His Majesty."

Instantly the boys were surrounded, and equally suddenly their guide, the self-styled Greville, vanished.

Blake kept his head.

"That is what I am in Plymouth for, sir," he said civilly. "There is no need to press me."

The officer laughed scornfully.

"I've heard that story before. It does not go down, my lad. Hold on to them, men."

Blake's colour rose at the insult.

"What I say is true," he answered sharply. "My name is Hawtrey. I am here to meet my uncle, Lord Chenton, who has procured for me a commission in his Majesty's Service."

"Ha! ha! A pretty tale for a country lad to tell! They grow them cunning in the Devon farms."

"You are pleased to insult me, sir," said Blake, with flashing eyes. "If you doubt my word, I have here a letter from my uncle, proving that what I say is true." As he spoke he thrust his hand into his breast pocket.

It came out empty. The letter was not there.

In a moment the staggering truth burst upon him. His pocket had been picked—and the culprit, no doubt, was the man who called himself Greville.

"A bluff! It is what the Yanks call a bluff," sneered the officer. "Now then, boy, I have no more time to waste on you. You will be wise to submit at once. I have the King's authority, and you disobey at your peril."

Young Judd suddenly burst loose from the men who held him.

"Master Blake tells you true, you black-faced ape!" he roared, and suddenly catching the officer by the throat hurled him to the ground.

"Run, Master Blake," he shouted.

It was useless. The seamen closed upon them. The odds were ten to one, and, though Amos fought magnificently, flinging the men to right and left, he and Blake were quickly overpowered.

The officer regained his feet. He thrust his dark face against Blake's.

"You mutinous hound!" he snarled. "You shall rue this night to the last day of your life."

"Take them away," he ordered. "Iron them when you get them aboard. By the Lord Harry, but I'll give them both a lesson before I'm done with them."

"NEVER mind Amos," said Blake Hawtrey. "Keep your spirits up. The Captain is bound to listen to me. All will yet be well."

Amos sat grimly silent. He looked as if he did not put much faith in Blake's comforting words, yet did not like to say so.

The two were seated on the bare floor of the lazarette of the big Salamis. It was a foul and noisome place, and so dark that, although it was now morning, the two could hardly see one another's faces. Outside, they could hear the plash of ripples against the planking; overhead bare feet thudded to and fro, and they caught the echo of hoarse orders.

Suddenly the hatch opened. A burly boatswain appeared. He had hands like legs of mutton, and on his bare arms were strange devices tattooed in Indian ink.

"Here, you! Captain'll see you, and sign you on. Sharp! We sails in a 'our. An' take my word for it, young fellers, you better be a bit more civil than you was to Lootenant Crosier last night."

Blake started sharply.

"Was that Lieutenant Crosier?"

"It were. And a purty tough customer, too, my lads. You never did a worse day's work than when you went for to put his back up. 'E won't forget it in a 'urry, I can tell ye."

As he spoke, he was unlocking their irons.

"You keep quiet, Amos," whispered Blake to young Judd. "I'll do the talking."

A minute later they were in the chart-room. The Captain—his name was Gallwey—sat at a table, a stupid, sodden-looking man, with a flushed face and his peruke awry. Behind him, to Blake's horror, stood his cousin, Ralph Crosier. There was a look of malignant triumph on his face.

"Names!" snapped the Captain; who was plainly in a peevish temper, caused, no doubt, by excesses overnight.

"My name, sir, is Blake Hawtrey," said Blake. "I am Lord Chenton's nephew, and—"

"I didn't ask whose nephew you were," retorted the Captain. "If you can write, sign your name here. If not, put a cross."

"I protest, sir," said Blake, with quiet dignity. "I tell you that I am Lord Chenton's nephew, and that I came to Plymouth on his promise to procure me a commission."

"If he's Chenton's nephew he must be your cousin, Crosier," said the Captain, turning to Crosier with a sly grin. "Do you admit the relationship?"

"I never saw the fellow in my life before, sir. It is an impudent masquerade. He looks like my lord's nephew, does he not?"

The Captain laughed vacantly. Blake could see in a moment that he was under Crosier's thumb, and realising that remonstrance was useless, decided suddenly to make the best of a bad job.

"No doubt Lieutenant Crosier has the best of reasons for denying our relationship," he said sarcastically. "Meantime—"

He took up the quill and signed his name in a firm hand, then passed the pen to Amos.

"You sign, too," he said. "We shall get our chance later," he added in a low voice.

"You'll get your chance of a hundred lashes if I have any more impudence from either of you," said Crosier, his dark eyes glowing with hate. Blake did not answer. He returned his cousin's glare coolly, and left the chart-room.

"Us be in for it now, Master Blake," said Amos ominously. "That chap's got eyes like a viper's."

"And the same temper, too, Amos. But you do your duty and keep clear of him, and all will be well. Ha, they are getting under weigh. That will keep him busy for a time, at any rate."

In this Blake was right, but once they were at sea they soon felt the weight of Crosier's ill will. Every filthy, dirty, and undignified job was put on Blake's shoulders. He was treated far worse than Amos, and at every possible opportunity Ralph Crosier lashed him with his evil tongue.

Life in a warship in those days was bad enough at best. The Salamis under Crosier—for Gallwey did not count—was a floating hell, and deep and dark were the murmurings of her crew.

Blake had two things in his favour. One, that he was never sea-sick, the other, that his quiet pluck and willingness soon made him a favourite with his mess-mates. As for Amos, the crew took him to their bosoms at once. The fact that he had knocked down the hated Crosier was a passport to their favour.

It was only the kindness of their fellows that made life bearable. Otherwise, Blake must have thrown up the sponge. All day and every day it was one lip-biting struggle not to turn on the brute who bullied him so wickedly. That was what Crosier was trying for. If he could only induce his cousin to turn upon him, he could have him tied up and lashed. And it was even betting whether Blake would ever have survived the awful ordeal of a hundred or even two hundred lashes. But Blake knew this as well as Crosier, and do what he would, the brute could not stir him to the hoped-for outbreak.

The Salamis sailed slowly southwards. She had letters of marque. But she was old and slow; her crew were badly disciplined and on the verge of mutiny. The more Blake saw of matters aboard, the greater were his doubts as to whether she would stand up against a Frenchman of her own tonnage, let alone anything larger.

As for himself, matters had reached such a pass that, as he said to Amos, "We should be no worse off in a French prison." And Amos, nodding his red head unsmilingly, agreed.

Blake's fears were only too well founded. They had passed through the Bay, and reached the latitude of Vigo, when they ran into fog—an unusual event in those waters. And when the mist began to clear, they found themselves within a mile of a great three-decker which was certainly not English.

Blake was in Crosier's watch, and he plainly saw the fear in his cousin's eyes as the latter caught sight of the tall ship, and he heard the quaver in his voice as he hastily gave orders to clap on all sail and make away.

His lip curled. So the fellow was coward as well as knave.

The man of-war broke out the Spanish flag, and turned in pursuit. Ordinarily speaking, a gun-brig like the Salamis should have been able to sail three knots to the Spaniard's two. But the Salamis was old and ill-found, her crew were ill-trained, most being pressed men, and consequently unhandy.

Also, the breeze was stiffening to half a gale, which gave the Spaniard a considerable advantage. She soon began to close, and then a long eighteen-pounder on her upper deck commenced to pitch round shot at the brig.

The shooting was bad. It was luck rather than skill that cut away the mizzen-topmast of the Salamis. In its fall it dragged down the main-topmast with it and the brig, utterly crippled, lay at the mercy of her big antagonist, which proved to be the seventy-four gun ship, the San Josef.

Even then Blake hoped she would make a fight for it. He almost choked with shame when he saw the white flag flutter out. The Salamis had surrendered without firing a shot.

Spanish boats came alongside; Spanish sailors, swarthy and reeking with garlic, swarmed over the brig. A prize crew was put aboard, and the Salamis' men were all taken aboard the San Josef and confined in her hold.

"So this be the end of it, Master Blake," said Amos Judd bitterly. "Us will spend the rest of the war in some stinking Spanish prison, I reckon."

And Blake for once was silent. He had no words of comfort.

"THIS be Crosier's work, I reckon, Master Blake," said Amos bitterly.

It was four days later, and the two lay together, but alone, in a little den off the after-hold of the San Josef. Their companions were on deck getting a breath of fresh air, but they two, of all the prisoners, had not been allowed up.

"Yes, I suppose that he has labelled us dangerous," replied Blake. "It is like his spite. Otherwise, we should certainly have been allowed up with the rest; for Captain Almeida, they say, is a true Spanish hidalgo, and treats his prisoners well."

"'Tis a pretty look-out for us when we get landed," said Amos. "They'll be handing of us over to the monks or something o' that sort."

"The Inquisition, you mean." Blake shuddered slightly.

"Amos, can we do nothing?" he added fiercely.

"Ay, Master Blake, we'll die fighting afore that," returned Amos.

Blake glanced at Amos in surprise. There was just light enough for him to see a grim smile on the other's face. His heart began to beat fast.

"Ay," repeated Amos. "They big muscles o' mine be some use, as Mistress said. I've worked them cords loose, and I reckon 'twon't be long afore I get my hands free."

"Splendid!" said Blake eagerly. "Keep at it, Amos."

Amos did, and though his wrists were raw from the strain it was less than an hour before his hands were free. Once he had done this, it was only a matter of a few minutes before he had unfastened the knots which bound Blake.

The two had been tied to a couple of ring-bolts, but with cords, not chains. Now they were, at any rate, free to explore the narrow limits of their prison.

The place where they were confined was below water line. The only light and air came through a grating overhead. They at once set to work to see if they could force this.

Between them they wrenched a long-shafted staple from the wall, and Amos, whose height enabled him to reach the grating, began on the fastening.

"Timber's rotten as punk," he said gleefully to Blake.

The words were hardly out of his mouth before a distant boom made the air tremble, then all of a sudden the whole ship thudded with the rush of feet.

The two boys stared at one another.

"A British ship!" gasped Blake. "A fight!"

Boom, again. Then, with a crash that made the great ship quiver, a whole broadside burst out.

"A battle!" cried Blake. But penned as they were in the darkness, neither could know that one of the greatest battles of naval history had begun—the tremendous fight off Cape St. Vincent.

Within a few moments the guns of the San Josef began to speak. The roar was deafening.

"There are other ships as well," cried Blake. "Listen! It must be a fleet action. Oh, Amos, why aren't we able to take our part?"

"Us soon will be, I reckon," declared Amos, setting to work on the grating with renewed energy. It mattered not how much noise he made. The roar outside drowned all lesser sounds. Hundreds of guns, many of them twenty-fours, were being fired at top speed.

From overhead came crash after crash, as the heavy round-shot, fired at almost point-blank range, tore through the timbers. Spars crashed down from aloft. Now and then a scream of agony rose above the tumult.

A heavy shot, striking the San Josef on the water line, just above the cell in which the boys were confined, splintered the ship's side, and sea-water came oozing through.

Blake and Amos hardly noticed. They were working like furies to get out of their prison. The wood, rotten with age, broke away in large flakes, but even so its thickness was so great that it took a long time to get through.

Amos gave a shout.

"Her'll go now. Up on my shoulders, Master Blake. Heave!"

To Blake's intense joy the grating lifted and fell back. But before he could clamber through, there came a shock which flung them both to the floor.

"They've boarded her!" cried Blake, picking himself up. "Our fellows are aboard her."

He was wrong. It was another Spanish ship, the San Nicolas, which, badly mauled by Commodore Nelson's own ship, the Captain, had swung round and fallen foul of the San Josef.

"Up you go again, master!" cried Amos, and picking up Blake in his mighty arms, literally flung him through the opening. A moment later he had followed himself.

The two found themselves on the lower deck. The place was thick with smoke. Through it they could see a few Spaniards still serving their guns, but most of the pieces were dismounted, and their crews lying dead around them. From overhead came stampings, shouts, all the sounds of furious hand-to-hand combat.

"Our fellows are aboard!" cried Blake, with flashing eyes. "Come, Amos. We may yet be in time to help."

He made a dash for the ladder leading up to the next deck. No one interfered. The few remaining Spaniards were too busy firing their guns. He reached the main deck some way ahead of Amos, and here the scene was similar. He was rushing towards the next ladder when down through the hatch above came a tall Spaniard, an officer by his dress. In one hand he carried a flaming torch, in the other a cocked pistol. His olive face was set and desperate.

Paying no attention whatever to Blake, he dashed past him, and dropped through the hatchway below. It was not until he had disappeared down it that Blake suspected his purpose.

He spun round.

"Stop him, Amos!" he shouted.

But the man was already past Amos, and Blake wasted no more breath. He tore after him.

Amos, slower in the uptake, and not understanding what was happening, wasted a second or two before following. By the time he had reached the hold Blake had disappeared.

He heard a wild yell of defiance, the ringing crack of a pistol shot, the thud of a heavy fall, and reached a doorway to find the Spanish officer flat on his back, with Blake on top of him.

"Hold him! Tie him, Amos," cried Blake hoarsely. "Don't let him get away."

Then he rolled over and lay quiet, the blood streaming from a wound over his temple.

Amos instantly pinned the Spaniard. The latter was in no case to resist. Indeed, his head seemed to be split open. Rapidly Amos tied him with his own neckerchief, then turned his attention to Blake.

Blake opened his eyes.

"It was the magazine, Amos. The fellow would have blown us all up. I hope I have not killed him."

"More like he's killed you," said Amos bitterly; but Blake did not hear him. He had fainted.

Amos gathered him in his great arms and went staggering towards the upper deck. His one idea was to find a surgeon, and in his haste he did not see a figure which stood back in the shadows, or a pair of dark and dangerous eyes which gleamed from the gloom.

"The cub is dead!" muttered Ralph Crosier, in tones of incredulous triumph. "My luck is in at last."

Dripping with perspiration, Amos laid his insensible burden in a quiet corner, and rushed off in search of a surgeon. So great was his anxiety on Blake's account he hardly noticed that the fighting was over, and the ship in British hands.

As luck had it, he ran upon Mr. Dougall, the surgeon of the Salamis, just finishing binding up the wounded arm of a young English lieutenant.

"My young master, sir. He's dying," he begged hoarsely, and Dougall, who was not a bad fellow, came at once.

Indeed, Blake looked like death, and the surgeon's face was grave as he bent over him, and with a pair of scissors began to snip away the blood-matted hair on his scalp. But when he came to the wound his face cleared.

"Cheer up, my lad," he said to Amos. "'Tis not so bad after all. The bone is but scraped, not broken. Your master, as you call him, will live to fight another day."

"Thanks be to God," said Amos reverently, and stood by while the surgeon dressed the wound.

With eyes fixed on Blake, Amos never noticed a slim, one-armed man in the uniform of a British Admiral who came past at that moment, accompanied by a taller, stouter man in the crimson tunic of the 69th Regiment. Both stopped close by, and the Admiral spoke kindly to a burly British tar, who, with one leg broken, lay propped against an overturned gun.

At the same moment two other men came up through the main hatch, bearing between them the insensible body of a Spanish officer, the very same whose bullet had come so near ending Blake's life.

The Admiral turned.

"Who is this?" he asked, in his quick, decided voice.

"An officer of the ship, sir," answered Ralph Crosier, who was one of the two bearers. "He was in the act of putting a torch into the magazine."

"And you prevented him?" Nelson exclaimed. "A very gallant action, sir. What is your name, and how is it that you who do not belong to my ship are here aboard the San Josef?"

"I am a prisoner of war, sir," answered Crosier. "I was first officer of the gun-brig Salamis, which was taken by this ship four days since. My name is Crosier."

Nelson fixed his piercing blue eyes on Crosier.

"So you lost your ship? Well, you have atoned for it. But for you, we should all have been blown sky-high ere now, I'll warrant."

"But for him! Why, he had naught to do with it, sir. 'Twas my young master here as stopped the chap from a-blowing of us up!"

And Amos, his honest face aglow with anger, towered suddenly over Crosier.

For a moment there was an amazed silence. Then Nelson himself spoke.

"What mean you, fellow?" he asked sharply.

"Just what I say, sir. 'Twas young Master Hawtrey as fought the Spaniard at the door o' the magazine, and nigh got his head blowed off for his pains."

Nelson's keen eyes studied Amos's face for a breathless instant. Then he turned to Crosier.

"Explain if you can, sir."

Ralph Crosier shrugged his shoulders.

"I think, sir, that the young man is over-excited, or perhaps it may be a wish for revenge. Unhappily, I was officer of the party who pressed him, a few weeks ago, and he has been heard to vow that he would be even. I have only to say that there is not a word of truth in his accusation."

"Liar!" cried Amos, with bitter scorn. "'Tis true ye pressed me—true, too, that ye pressed your cousin here, and did it for dark purposes o' your own."

Crosier did not turn a hair. He turned to the Admiral.

"I hardly think I need say more, sir. The mere fact that this youth, whom I have never seen before he was pressed, claims to be my cousin, Blake Hawtrey, is in itself sufficient proof that the whole story is an invention."

Nelson glanced at Blake, who was still insensible. He was indeed a pitiable object; dirty, blood-stained and roughly dressed in the garments of an ordinary seaman. He realised that Crosier had all the weight of evidence on his side, and that it was absurd to doubt him. Yet, with his keen insight, he had felt the ring of truth in Amos Judd's indignant words.

And while he hesitated, came a most dramatic interruption. The Spaniard, whom all had thought to be dying, sat up and gazed around him. His fierce eyes fell upon the British uniforms, and a groan escaped him.

"Then I failed!" he cried despairingly.

Nelson, always the first to acknowledge gallantry in an enemy, spoke courteously.

"You failed, sir, and for that we are all thankful. But even an enemy can honour a brave man, and can believe that he will not be the last to be grateful for the failure of so desperate a project."

But the Spaniard took no comfort.

"To be foiled at the last moment!" he groaned, "and that by a mere lad!"

Instantly Nelson was all attention.

"A lad, you say, sir. Can you recognise the one who stopped you at the door of the magazine?"

The Spaniard looked round, and his glance fell on Blake.

"There he lies!" he said. "I fear I have slain him, but the mischief was done. This big fellow was on me before I was able to rise."

The conversation had been in Spanish, but Crosier had understood. Now Nelson turned upon him, and in the flashing eyes of the Admiral the villain read his condemnation.

He turned and ran.

"Stop him!" cried Nelson.

It was too late.

With a bound, Ralph Crosier reached the side, and springing through a gap in the broken rail, plunged headlong into the blood-stained sea. Nor did he rise again.

"Sic pereunt!" quoted the Admiral gravely, then turned once more to Amos.

"My lad, you spoke well. I am pleased with your loyalty to your master. Master surgeon, see that your patient is brought aboard the Captain as soon as he can be moved, and that every care be taken of him."

So it was that, twenty-four hours later, Blake, with his head bound up, and still somewhat pale from loss of blood, found himself in Nelson's own cabin, telling his story to the "Little Admiral."

Nelson heard him to the end before he spoke.

"My lad," he said, "you have done well, and you are well rid of this cousin of yours, who, it is plain, meant you no good. You tell me that my Lord Chenton promised you a commission in His Majesty's Navy. There shall be no need for him to extend his favour, for I myself will see to the matter.

"No"—as Blake began to stammer out his thanks—"there is no need to thank me. I and many others owe you our lives, and this is but scant payment of your services. Is there aught else you would ask?"

"There are two things, sir," Blake answered. "One, that I might not be separated from Amos Judd; the other, if it please you, that we might both be allowed to serve on your ship."

Nelson's rare but charming smile illumined his thin face.

"Both granted, my lad. Both your requests are granted. Now go and tell your young giant that he and you are enrolled aboard this ship."

Blake left the cabin with his head high and his eyes sparkling. He asked nothing better than to serve under the great little man who had been so kind to him.

Nelson kept his word. In every commission from then onward, Blake Hawtrey was in Nelson's own ship, until in 1805 he became lieutenant aboard the Victory and took part in that greatest of all sea-fights off Cap Trafalgar on October 21 of that year.

But his joy in the victory was marred by the death of his great commander, and as soon as peace was declared he retired from the Service.

By this time Lord Chenton was dead, and Blake succeeded to great titles and possessions.

But the lessons of his early days were never forgotten, and to the end of his life he kept on the little cottage at Withycombe, and there, in company with Amos, he would spend his happiest days, catching trout in the brook or shooting on the open moor.

HEAD down, facing the chill autumn wind, Sam Eccles strode heavily down the main street of Moorlands.

"Hallo, Sam, you look a bit peaked," came a kindly voice, and Sam, glancing up, found himself face to face with a square-built man of middle age dressed in a dark blue uniform. On his shoulder the letters "P.W." in brass showed that he was a Principal Warder at the great prison which stood at the upper end of the long village street.

"Peaked!" repeated Sam, with a look of bitterness which sat oddly on his usually cheerful face. "I've a right to be, Mr. Taber. They've turned me down."

"What! For the police?"

"That's it."

Sam held up his right hand from which the top joint of the forefinger was missing.

"Just because of that," he said.

"It's hard," declared Taber. "Mighty hard. 'Tis a foolish thing for sure to turn down a likely young fellow like you.

"But I must be getting on," he added quickly. "I've got to go on duty down to Harrowell."

"What for?" asked Sam, astonished.

"Haven't you heard? No, of course you've been away all day. There's a chap done a bunk this morning. Ran from Stonebrook Newtake in that storm of rain. Beddoes his name is. 'Big Beddoes,' they call him."

"I've heard of him," said Sam. "Your boy Dicky told me. Bad lot, isn't he?"

"The worst," replied Taber, with emphasis. "Well, good-bye, Sam. See you again some day soon."

He hurried off, and Sam walked on. At first the exciting news of the escape filled his thoughts, but this soon passed, his head sank again, and the light went out of his clear gray eyes.

Down the long hill he tramped, the wind blowing cold out of a dull sky, and when he came to the bridge over the Stone Brook he found another warder on guard there, with his overcoat collar turned up to shield his cheeks from the bitter breeze.

"Seen anything of our chap, Eccles?" asked the warder.

Sam shook his head.

"I'm just up by the train," he answered.

"Well, keep your eyes skinned," said the other.

"Did he go our way?" asked Sam.

"No, he ran north to start with. Most like he's up on the High Moor. I only hope we'll get him before dark. It'll be no sort of night to spend out o' doors."

"I hope so, too," agreed Sam, and went on.

Stonelake Cot, where he lived with his mother and sister and younger brother, was four miles out by road, but there was a shorter cut across the moor. Turning to the right, he climbed the wall, and made across the rough boggy ground, picking his way among the sopping heather and gray boulders.

Again his thoughts went back to his bitter disappointment of the morning. He had always wanted to wear the blue uniform, and now that his brother was old enough to look after the little farm, it seemed that his chance had come.

It had never occurred to him for a moment that the finger damaged in a quarry accident, two years before, would stand in his way. Apart from that, he knew himself to be as fit and strong as any young fellow of his age for miles round.

He had gone down to Tarnmouth by the early train, full of hope and pleased with himself and every one else. Now he was coming back, plunged in despair, and feeling as if life was hardly worth living.

The path led down into Giant's Gorge, a deep ravine which was really an old surface tin working. A thin mist driven by the wind swirled among the great rocks which cumbered the gloomy place.

Sam knew every inch of the way. He did not trouble to look to one side or the other. It was not often that he was so careless, and now he was to pay for it. Silent as a ghost, a drab clad figure rose from behind a huge boulder and sprang on him from behind.

Sam never saw the man. All he knew was that he was suddenly flung flat upon his face with a force that half stunned him. Fingers, hard as boards, clutched his neck. He struggled desperately, but the choking grip did not relax. Black specks danced before his eyes, and presently he lay limp and insensible.

SAM'S teeth were chattering. He was chilled to the very bone. Those were his first sensations as he came to himself again.

Small wonder, for presently he realised that he had nothing on but his underclothes. His good blue suit, his cap and overcoat, all were gone. His boots had also been pulled off, but they lay close by. So, too, did a suit of hideous drab garments plentifully besprinkled with broad arrows. There was no need to look farther. They explained the whole situation.

Sam sat up. He had a bump on his forehead as big as a small egg, and was feeling sick and dizzy.

"So 'twas Beddoes!" he muttered ruefully. "And serve me right for being such a careless fool!"

He stood up, shivering, and picked up the lag's discarded garments. He looked at them with great distaste.

"Nice things to meet mother in!" he observed. "Well, it's Hobson's choice, and I'll perish if I don't put something on."

He got into them quickly and walked on fast.

He was hardly out of the ravine before a figure dimly seen in the mist dodged out of the path behind a clump of gorse.

He made a dash at it. As he reached the gorse the figure rose suddenly and flung itself upon him.

But Sam was not to be caught napping a second time. He threw his arms around it and bore it to the ground.

It went down with unexpected ease.

"Why—why!" gasped Sam, as he realised that it was a mere boy he had hold of. "I thought it was Beddoes."

"Beddoes, you idiot! Aren't you Beddoes?" came the indignant reply.

Sam let go and jumped up.

"Great Christopher! It's Dicky Taber."

The other, a red-headed boy of about sixteen, with a jolly freckled face, stared at his aggressor for a moment, then went off into a shriek of laughter.

"Oh! Oh!" he gasped. "It's Sam!"

He lay back and rolled on the wet grass in paroxysms of mirth.

"Dry up, you young idiot!" growled Sam. "Here, get up off that grass."

Dicky Taber struggled to his feet.

"Oh, Sam, I made sure you were Beddoes!" he gasped out.

"And I thought you were," replied Sam, rather sheepishly.

"What's happened?" asked Dicky, wiping his eyes with his handkerchief.

Sam explained, and told Dicky how he had come to be caught napping.

"It was Big Beddoes, of course," said Dicky, suddenly grave. "And just to think I missed him by so little! I found his marks by the brook over there and have been trailing 'em for an hour. You can spot the broad arrows on the soles of his boots wherever the ground's a bit soft."

Sam looked thoughtful.

"Tell you what, Dicky. There's no sense in giving up. If you tracked him this far, the two of us ought to be able to get him. What do you say?"

"Rather!" replied Dicky delightedly. "Specially as you know the moor better than any of our chaps up at the prison."

He paused and looked doubtfully at the other.

"But I say, Sam, are you fit to go on? You've got a baddish bump on your head."

"That don't signify. Besides, the beggar's stolen my best suit o' clothes. I'm bound to have them back some way."

"Right-o! The only thing is that you'll have to look out for warders or they'll be running you in like I tried to."

"I'll not go to sleep again," returned Sam grimly. "Now let's go back along to Giant's Gorge. That's where we pick up the trail."

The arrow-marks of the convict's nailed boots were plain enough all round the spot where Sam had been attacked, but it was some minutes before they found that Beddoes had gone straight on up the Gorge.

The Gorge sloped upwards to the north-east for nearly a mile. They found the marks where Beddoes had scrambled up the steep slope at the upper end, and followed them on to a bleak and empty hill-side.

"Where do you reckon he's gone now?" asked Dicky Taber, coming to a stop.

Sam, a queer figure in the lag's discarded attire, stood staring uphill through the thin mist.

"Okestock," he said slowly. "He'll be making across Radden Ridge, then he'll lay up somewhere below the Artillery Camp and make a push for the junction. There's trains in plenty, and now he's got my clothes and the money in 'em he'll either stow away in a truck or take a ticket for Bristol."

Dicky nodded. "I expect you're right. But see here, Sam, there won't be much in the way of marks up among the stones here. Hadn't we best cut right across the ridge and look for his tracks along the edge of the boggy ground down below?"

"That's a good notion. He's bound to leave a trail somewhere along the valley. Come on."

Sam, who was hard as nails, had almost got over the effects of his mauling, and as for Dicky, he was as wiry as they make them. The two wasted little time in crossing the ridge.

They were pushing rapidly down the far side when a strong gust of wind suddenly swept up the mist, and in a moment opened up the whole of the wide, desolate valley below.

Dicky seized Sam by the arm and dragged him down behind a rock.

"I see him," he whispered breathlessly.

"WHERE?—ah, I've spotted him. Right away up to the left. But what in the name o' goodness is he doing there?"

"Blessed if I know," returned the boy. "He's clean off the Okestock track. And yet he knows the moor pretty well. I heard father say so this morning."

Sam started.

"I've got it, Dicky. He means to make a short cut up Challacombe Cleave."

Dicky turned eagerly to the other.

"Challacombe Cleave," he repeated. "But that leads right into Merlin's Mire."

"So it does. All the same, there's a way through. By Jinks, I wonder if he knows it."

"I don't," confessed Dicky. "I was up there last winter after snipe, but it was as ugly a place as ever I hit. I came back the same way I went."

"I reckon you did. You'd never find the cut unless you knew. You have to climb up the right-hand side of the Cleave a good piece before you reach the edge of the bog. There's a ledge runs all the way, but you can't see it from below.

"If Beddoes knows it," he added, "he can save all that climb over Radden."

"And beat us out," put in Dicky sadly.

"Wait," said Sam quickly. "Wait a jiffy. I reckon we can diddle him after all."

"How?—how?"

"Just listen to me. He'll be out of sight in a minute in the mouth of the Cleave. Then I shall start and run for the Ridge, and up along the east side of the Cleave. It's farther than he has to go, but he'll have to be mighty careful, while I can run all the way. What I'm after is to get to the neck of the Cleave ahead of him. I'll wait for him on the ledge just round the corner above the bog, hide behind a rock, and take him by surprise as he comes past."

"I see. But what about me?" questioned Dicky.

"Why, Dicky, you'll have to go right back to the prison and fetch help. I don't reckon I can bring him in alone—especially in this rig!"

"But why shouldn't I come along with you?" demanded the boy, in a sadly disappointed tone.

"Because we aren't taking any risks, that's why. I'm sorry, Dick, but you'll have to go."

When Sam spoke in this tone, Dicky knew it was no use to remonstrate.

"All right. I'll be as quick as I can."

He started off, then turned.

"Be a bit careful, Sam," he said quickly. "Big Beddoes is a pretty hard case. He wouldn't stop at much, you mind that."

Sam nodded. Then, as he saw the convict disappear between the cliffs which hemmed in the Cleave, he rose to his feet, and set off at a swinging trot.

It was no easy job he had before him. Even if he could reach the Neck above the Mire before Beddoes he still had to stop him, and he had no weapons of any sort—not even the truncheon which warders carry.

But he hardly thought of that. He was very sore at having been caught so easily, and he fully meant to have his best suit back. And Sam Eccles, when he had once made up his mind to anything, was not an easy person to turn from his purpose.

He kept going hard till he was across the valley, then slackened as he began to climb the opposite slope. There was no sense in winding himself. The mist kept rising and falling, but never grew very thick.

When he reached the top of the great bare ridge there was not a living thing in sight.

He began to run again, and in another ten minutes had reached the edge of the Cleave at its southern end.

He peered cautiously over, but there was no sign of Beddoes. The convict, no doubt, had already rounded a bend some way farther up.

Sam set off again as hard as he could go, and made such good time that, when he reached the upper end of the Gorge, he was ready to bet that he was well ahead of the convict. At the north end of the Cleave was a sort of bowl. The sides were steep, but not precipices like those of the Cleave itself. The bottom was all marsh, but the worst of the marsh was just at the exit from the Gorge.

Here was a vast pool of black slime covered with great patches of livid green bog moss. Old moormen believed the place to be bottomless. Dozens of cattle and ponies had been swallowed there, and never a horn or hoof seen again. Sam shivered a little as he thought of all the skeletons down in those oozy depths.

He went quickly down the slope, but trod carefully. It would not do to start loose stones. To his left opened the upper gate of the Cleave. Dusk was beginning to fall, and the mist lay thick in the gloom of the darksome ravine.

When about twenty feet above the level of the mire, he turned sharp to the left and worked along towards the mouth of the cleft. The bank grew rapidly steeper, and soon he was scrambling along the side of a rocky cliff. The mire lay directly beneath him, and a single false step would send him plunging down into its thick black slime.

But Sam made no false steps. He had been here before, and his head was as steady as any man's on the moor. Within a very short time he had reached the spot of which he had spoken to Dicky, and there he pulled up and waited.

A great rounded boulder bulged from the cliff face, and the ledge, here not much more than a foot wide, ran round the outside of it. It was quite impossible for a person coming up the Cleave to see another hidden behind the boulder until he had clambered round it.

Sam stood very still. His heart was beating a little more quickly than usual, but his square, honest face and steady gray eyes showed no signs of any inward uneasiness.

For some minutes he waited, listening hard. Then all of a sudden he bent forward a little. A rustling, scratching sound had reached his ears, and he knew that his man was very close.

"ALL right, my beauty, it's my turn this time," he muttered soundlessly.

Then, before he expected it, a large dirty hand came into sight, feeling for a hold around the curve of the boulder.

Like a flash Sam reached out and grabbed the thick brown wrist.

A yell of terror went ringing down the Cleave, sending the echoes beating in an extraordinary fashion. The hand was jerked back with such force that, if Sam had not already braced himself, he would certainly have been pulled right over the edge.

"No, you don't," said Sam, as he laid his weight back. "It's a fair cop, and you may just as well come now as later."

But Big Beddoes apparently did not share his opinion. He pulled and jerked with surprising force and fury, while the threats he poured forth were of a positively blood-curdling character.

Sam's quick ears caught a low but ominous cracking sound. "Chuck it, you fool!" he cried. "The rock won't stand this sort o' game."

But Beddoes only pulled the harder.

The cracking came again. Bits of earth and gravel began trickling down the face of the cliff. The cracking changed to a crunch, and Sam had just time to let go of Beddoes and spring back to safety before the ledge outside the big rock broke away and fell with a loud crash into the valley below.

High above the crash came a wild shriek of terror. Sam saw a great burly figure falling outwards from the cliff, clutching vainly at thin air. Then with a heavy splash Big Beddoes landed on his back in the mire beneath, sending up a splatter of ink-black spray.

Before Sam could recover from the shock, there was a fresh and much louder cracking, and to his horror he saw that the great boulder itself was coming away bodily from the cliff face.

Slowly and majestically it bent outwards, seemed to hang suspended for a second or two, then turned over and dropped with a sullen plunge into the great slime pit.

A geyser of mud rose as high as the ledge itself, spattering Sam all over and half blinding him with the ill-smelling filth.

With the sleeve of the convict jacket he dashed the horrible stuff from his eyes, and stepped quickly forward to the edge of the ledge.

An amazed exclamation burst from his lips. He had never expected to see Beddoes again. He had, of course, felt absolutely certain that the man had been crushed under the ponderous mass of stone.

To his intense astonishment, Beddoes was still visible. Apparently the rock had turned in its fall. It lay some yards to the left of the lag, its gray top just visible like an island in a pool of ink. Beddoes, up to the waist in the mire and sinking steadily, was making frantic efforts to reach it.

Frantic, but quite useless. The mire held him like glue. Unless help came his doom was sealed.

His great gaunt face was turned upwards, his deep-set eyes, dull with terror, were fixed on Sam.

"Help!" he moaned. "Help!"

"A fat lot of help you'd give me if I was there, and you up here," growled Sam. "Keep still, you idiot! Spread your arms out. Don't struggle. I'll give you a hand when I get down."

He flung himself flat on his face and examined the cliff face below the ledge. His quick eyes caught a little jut of rock some six feet beneath. Deliberately he turned round with his face to the cliff, grasped the edge of the path with both hands, and felt with his toes till he found the projection.

He got foothold, then very cautiously turned round. The risk was extreme. If the projection broke away, if he slipped or lost his balance, he was done for. He knew that quite well, but did not hesitate.

From this projection he reached another a little to the left and about five feet lower. Below, the cliff face was sheer.

"Got to jump for it," he muttered, as he judged with his eyes the distance between his narrow perch and the top of the boulder.

"I reckon watching won't make it look any prettier," he remarked, with a wry smile, as he balanced himself carefully. Next moment he had taken off.

For a hideous instant he thought he had missed his mark. He did drop a little short, but his outspread arms reached the top of the boulder, and he lay there for a few seconds breathing hard and up to his waist in the cold mire.

Then he pulled himself up and gained his feet.

Even now he was out of reach of Beddoes. Only a yard or two, however, and that was easily remedied. He pulled off the slop jacket, and holding it by one sleeve flung it across to its proper owner, who grasped it with the energy of despair.

"Pull me up," said the lag hoarsely. "Pull me up. I'm perishing cold."

Sam looked at the man, looked at the little island of stone on which he stood himself.

"Can't be done, Beddoes. No room for two. You'll have to stick it out till help comes."

Beddoes' great coarse face was convulsed with rage.

"Pull me up!" he cried, with an oath. "Pull me up, or I'll do you in when I get my 'ands on you."

"Ah, that's just what I thought you'd do," returned Sam mildly. "Now, if I were you, I'd keep quiet, or maybe, if you don't, I'll let go altogether."

"I feel almost tempted to recommend you to do so, Eccles," came a calm, leisurely voice from the far side of the bog. Sam, looking up sharply, saw a square-set man, with a fair moustache and sleepy blue eyes seated on a horse, close to the opposite edge of the mire.

It was Captain Noble, deputy-governor of the prison.

"I didn't mean no 'arm," whined Beddoes, all his bluster gone in a moment.

"I'm sure you didn't," drawled Noble. "At any rate I will take good care you have no chance to do any for some time to come."

"Eccles," he continued, in his quiet voice. "I've got a rope. Your young friend Dicky Taber advised me to bring one. Just hang on to that joker a minute, while I tie my horse and come round the head of the bog. I think I can get you out without much trouble."

Captain Noble, being known far and wide as one of the strongest men in the prison service, had no great difficulty in carrying out his undertaking, and as soon as Sam was safe on the ledge, he and the deputy, between them, drew Beddoes out of the mire and towed him out on the more level ground at the head of the Cleave.

By this time Dicky had arrived with two warders, and the latter taking charge of Beddoes marched him off.

"I say," said Sam anxiously, as they started. "Those are my clothes Beddoes is wearing. You'll remember that, if you please."

"Ah," said Captain Noble softly, "now we begin to understand why you took all that trouble to get the beggar out, Eccles."

Sam smiled ruefully.

"It's my best suit, sir."

"Was, you mean. I'm afraid it won't be much use to any one after this—"

He paused, and regarded Sam thoughtfully.

"How would you like to exchange it for another?" he asked.

Sam stared.

"Also blue," said Noble. "See here, young Taber tells me you've been turned down for the Police. But if it's only that finger, that won't bar you from prison service. And as we've lost a lot of our ex-service chaps, we are very short-handed, and want good men. Think it over, Eccles."

"No need to think, sir," answered Sam promptly. "I say yes now."

"Good man!" said Noble. "Then come and see me to-morrow."

He turned his horse.

"Good-night," he said, and cantered off.

Dicky stared at Sam.

"So you're coming on as a warder?"

"Looks like it," said Sam.

Dicky flung his cap in the air.

"Hurray!" he shouted gleefully.

GUN on shoulder, Don, his big water spaniel, at his heels, Bob Wetherell was in the act of opening the gate leading into the Upper Marsh, when he was met by a square-set man in gaiters who was a complete stranger to him.

"I'm sorry, sir," said the latter, "but you can't shoot here."

Bob stared.

"Can't shoot here," he repeated. "Why I've shot here all my life."

"You can't do so any longer, sir. My orders are that the marshes are to be preserved as well as the covers."

The man's tone was perfectly respectful, but very firm.

"Whose orders are those?" asked Bob rather sharply.

"My employer's, sir, Mr. Cassidy's. He's taken Saltern Park, and he wants a good head of hares on the marshes."

"But I'm not going to shoot hares. I'm after wild fowl."

"Yes, sir, but you can't come on the marshes without Mr. Cassidy's leave. You'll have to try the sea wall down below."

Bob looked grave.

"There'll be trouble about this, you know," he said. "It does not matter so much to me, for with me it's only sport. But the marshmen won't take it so easy. It's their livelihood."

"I can't help that, sir. I have my orders."

"I understand. It's no fault of yours. But I tell you straight I shall call on Mr. Cassidy, and put the thing before him."

The keeper shook his head.

"I'm afraid you won't do no good, sir. Still, of course, you can try."

"I shall try at once. I shall go up to the house this afternoon. Good-morning."

Bob was only just home from school. That was why he had heard nothing of the new tenant of Saltern Park. On his way home he met old Peter Cray, one of the finest fowlers on the coast. The old chap was boiling.

"It's a shame, Master Robert, a right-down shame. Him with all his money to go for to stop us a-shooting the duck. I never did hear such a thing. And me with two sons in the Navy. But there—he's a furriner, and what do he care for the likes of we?"

"A foreigner?" repeated Bob.

"Ay. Comes from America, he do. Why, a French would know better. There'll be trouble, Master Robert. Mark my words, there'll be trouble."

"Well, wait till I've seen him," said Bob. "It may be that he doesn't know the way of things. I'm going there this afternoon."

"I hopes you'll have luck," said Peter. "But I doubt it."

Peter's doubts were justified. Arrived at Saltern, Bob was informed by a pompous-looking butler that his master was away from home. Bob asked to see the agent, and was directed to his house.

The agent, a sharp-faced man named Deane, had no comfort to offer.

"I can do nothing, Mr. Wetherell. Mr. Cassidy gave me certain directions, and I must carry them out. And if you will allow me to say so, I don't know what you are complaining of. The marshes belong to the Saltern Estate. Mr. Cassidy has a perfect right to close them."

"I know that," said Bob bluntly. "But they have been open to all the fowlers ever since any one can remember, and if Mr. Cassidy knew how hot the feeling is, and how many men stand to lose their livelihood, I believe he would think twice before closing them."

"That is not my opinion," answered Deane with cold politeness. "Good-day to you."

Bob went home, feeling very sore and angry. As he came across the dyke by the Lower Marsh, he met a big brown-faced boy in a knitted blue jersey and stocking cap. He was Dan Cray, old Peter's grandson.

"Any luck, Master Robert," inquired the boy eagerly.

"None," growled Bob. "Mr. Cassidy's away, and the agent says we've got nothing to kick about—that the marshes are Mr. Cassidy's to do as he likes with."

"Dad was afeared you wouldn't get no satisfaction," answered the boy, shaking his head. "There be chaps putting up barbed wire all along the marshes this minute."

"It's too bad, Dan," said Bob. "Especially now the frost has come at last. There'll be plenty of fowl in the creek by to-morrow."

"And plenty of ice, too," said Dan, glancing up at the red sunset. "'Tis peering proper to-night. We won't be able to take a punt out or maybe we'd pick up some widgeon off the flats."

Bob looked at the creek. The wide expanse of dull gray water was rimmed on either side by broad bands of white. Up to high-water mark the saltings were covered thick with musky ice, and now it was freezing harder than ever. The next tide would lift all that stuff and fill the creek with floes.

"No, we'll never get a punt out, Dan. But I'll tell you what. I shall go down to the lower sea wall after breakfast to-morrow, and see if I can bag a few mallard or teal. If you come along you can have any birds I get."

"I'll come—and gladly, Master Robert," answered the boy. "Good-night to 'ee."

He was off, and Bob went home to Netherham, where his father, a country squire of the old school, ruled a snug little estate of some six hundred acres. Bob, however, said nothing to him of the day's doings. Mr. Wetherell's temper was hot, and if he heard of Cassidy's high-handed action he would certainly fly into a rage, and perhaps do something that afterwards he would regret.

Bob had an early breakfast next morning, and by nine o'clock he and the spaniel were down by the sea wall, where Dan was already waiting.

"'Tis proper hard this morning," said Dan. "Have 'ee seed the creek, sir?"

"Only from the distance. But I could see there was lots of ice."

"It's all a-going down with the tide. You can hear it from here."

It was true. Even through the great thickness of the high sea wall there came to their ears a constant rustling, varied by an occasional heavy crunching sound. The floes were just beginning to go out with the ebb.

"What about birds?" asked Bob.

"There's plenty out on the watch," answered Dan. "Sheldrake mostly and a loot o' coots. There'll be some on the saltings as they begins to bare."

"Lets go up and have a look," said Bob, and began creeping up the slope of the grass-covered embankment.

The saltings had only just begun to bare; and there were no birds in the mud. But the creek itself was worth watching. Its whole surface, gleaming under the red winter sun, was dotted with regular arctic ice-floes. Some were mere rafts of ice, others were piled up to a height of three or four feet above the surface. There were thousands of them, all moving down in a long stately procession towards the sea.

Some sailed steadily, others spun round, caught in tidal eddies. Frequently one would catch another and crash into it, at times riding right over it and driving it under water. These floes were all white as snow, and shone brilliantly in the pale sunlight.

Bob turned to Dan.

"No, it's no place for a boat," he remarked.

"You're right, Master Robert. I'd be main sorry to take a punt out in that. They big ice rafts would break her like a eggshell."

"Hallo, there's some one at it already!" said Bob sharply, as the distant report of a gun came from far up the creek.

"Get your head down," urged Dan. "Get down low, sir. That'll send the birds right along over us."

He was right. Next minute a couple of teal came sailing overhead, their short wings working vigorously, and driving them at the pace of an express train.

Bob flung up his gun. Two reports rang out in quick succession, and one of the two teal shot downwards in a long volplane, striking the top of the dyke fifty yards behind them and bouncing along it.

"Seek, Don!" said Bob, and the spaniel dashed off, to return in a minute carrying the dead bird carefully in his mouth.

"There'll likely be some more down soon," said Dan, and sure enough a couple of mallard flew over a few minutes later, and Bob got them both.

Then came a long pause.

"That chap above has stopped shooting," said Bob. "I wonder why. There ought to be plenty of fowl up that way."

The words were hardly out of his mouth before there came two shots, and then, in quick succession, two more.

"Hallo, he's a lot closer," said Bob, and cautiously put up his head over the edge of the bank.

Next moment he was on his feet.

"The idiot!" he cried. "Look at him! he must be crazy."

Dan sprang up.

"Ay,—crazy sure enough," he said gravely. "Didn't he know no better than to get in that there boat?"

For a few moments the two boys stood side by side on the top of the sea wall, watching a small boat which had just appeared in sight around a bend in the creek above. She was only a little cockle shell of a dinghy, and in her was a boy who looked to be about fifteen. He was sitting in the stern, paddling with one oar, and as they watched him, he picked up his gun again and fired shots, evidently as signals of distress.

The ice was all around him, and the tide, now running faster every minute as the ebb grew stronger, was carrying him swiftly down towards the open sea. But the sea was two miles away, and, long before he could reach it, the dinghy must be caught and crushed between the ice.

A great floe swept sideways at the dinghy. The boy flung down his gun, and seizing the paddle in both hands drove his little craft forward. Next instant the floe had caught another, and the crash of their meeting came plainly to the ears of the watchers. The dinghy was safe, but only for the moment. Below her the ice was thicker than ever.

"Come on! Come on!" cried Bob, suddenly starting forward. "We can't let him drown."

The two ran together down the wall and out across the saltings through the freezing mud to the edge of the cold gray water.

The boy in the boat saw them.

"Help!" he shouted, "help!"

"'Tis all very well to talk about help, but us can't get near him," said Dan.

Bob put both hands to his mouth to form a speaking trumpet.

"Paddle in. Shove her in as close as you can."

"That's what I'm trying to do," shouted back the other. "But I've lost one oar, and the tide's running like smoke."

Another great chunk of ice bore down on him as he spoke, and one end of it caught the dinghy and ran under her. She tipped half over, and it seemed a miracle she did not upset. Bob felt half frantic.

"This is ghastly," he said to Dan. "Can't we do anything? Where's the nearest boat?"

"None nearer than Graystone," answered Dan. "Two mile away if it's an inch. I reckon he've got to save hisself or drown."

Dan only put into words what Bob was thinking. They could do nothing but watch and wait.

As for the boy in the boat, he had pluck, for he kept his head, and whenever he saw half a chance drove the dinghy a little closer to the shore.

By a series of miracles he got safe through fifty yards or more of the ice run, and, by the time he was opposite the spot where Bob and Dan were standing, he was not more than thirty yards from the shore.

But here was the very worst of it. Some freak of the tide had brought in so much ice that there was more ice than water. As Bob watched breathlessly he saw a little cave open between the packed floes.

"Now!" he shouted at the pitch of his voice. "Now, take your chance."

The boy saw, and with all his strength drove the dinghy into the gap.

"Hurray!" cried Bob. "That's right, You'll do it!"

At that very instant he saw the dinghy suddenly tilt. A long narrow piece of ice, which had somehow been forced beneath the rest, had risen to the surface exactly under the boat.

Slowly but surely she tilted, until the water began to run in over the gunwale. The boy flung his weight across; he did his level best to force her off with his oar. It was no use. The keel came into view, then quite suddenly over she went altogether, shooting her occupant out into the icy water.

Even now he did not lose his head. He was up again in a minute, and, grasping hold of the edge of one of the floes, began trying to pull himself on to it.

But he could not do it, and by the look on his face Bob saw that he knew his number was up.

"I can't stand this," said Bob in a sort of groan, and before Dan knew what he was about, he had made a flying leap on to the nearest floe.

"Come back! Come back!" cried Dan in horror. "'Tis no good two being drowned instead of one."

Bob paid no attention. The sight of the other boy drowning before his eyes had screwed him up to a pitch of absolute recklessness. If he had stopped to think, he would have known that he was going to almost certain death, for, even if the floes were big enough to bear his weight, this salt water ice was rotten slushy stuff, much of it no better than half-frozen snow.

In spite of the madness that had seized him—because of it, perhaps—he had never been cooler-headed in all his life. He landed clean and clear in the centre of the floe, balanced while he looked for another strong enough to bear his weight, then sprang again.

The second began to sink under him, but, even as the water gushed over it, Bob was off it and on to another much larger.

He was now half-way across the gap which separated him from the other, but here he had to stop a moment, until another ice raft large enough for his purpose drew near.

"Hold on!" he shouted, and his clear confident tones gave the boy fresh courage. "Hold on tight. I'll have you out."

His floe banged against another with a shock that nearly knocked him off his balance, but the new one was fairly big too, and he made a fourth jump in safety.

The next one beyond was wide but low and slushy. It looked all odds against its holding him, but a quick glance at the boy showed that he must risk it, for the latter, being farther out from the shore, was being carried down the more rapidly, and would soon be out of reach. He waited until it was quite close, stepped lightly upon it, and slid rather than ran to the far side. It was actually breaking under his weight as he flung himself on to another, and landed on hands and knees.

This one was a good two feet out of the water, and though slushy on the top there was plenty of solid stuff in it.

Looking over to the far side, he found himself within a few feet of the drowning boy.

"Swim!" he cried. "If I can get you up on this one you'll be all right."

The boy pluckily let go of the piece of ice to which he was clinging and struck out. But he was cramped with cold, and had not strength enough to struggle against the swiftly running tide.

Bob was in an agony. To be so near and yet unable to help was simply ghastly. He was on the point of plunging in, yet knowing perfectly well that, if he did, he would never be able to climb back, let alone hoist the other up.

"Your coat," muttered the boy hoarsely, and Bob, calling himself an idiot for not having thought of it before, whipped off his thick Norfolk jacket and, holding it by one sleeve, flung it across to the swimmer, who just managed to grasp it before being swept out of reach.

When the strain came Bob felt himself slipping. He flung himself flat on his face in the slush, and digging in his toes hauled for all he was worth. Next minute he had the boy close enough to grasp him by the collar.

Then came the worst of it all. The boy by this time, was practically helpless. Bob had to haul him out of the water by main force. There was not only the danger of slipping, but the floe itself threatened every moment to turn turtle. If it did—why, there was the end of things for them both.

When in the end he had the boy safe on top of the floe, he was so done that he could hardly breathe, much less think of how they were going to get back again.

At last he pulled himself together and scrambled to his feet again.

"Dan!" he called, "Dan!"

There was no answer. He looked back towards the shore.

Dan had vanished. There was not a sign of him or of any one else.

"Suppose he's gone for help," he said blankly. "But I wish he'd stopped to give us a hand."

"I say"—this to the boy whom he had pulled out, and who was still lying all in a heap on the ice—"how do you feel? Are you up to trying to get ashore?"

"There isn't much jumping power left in me," he answered between chattering teeth. "Tell you the truth, I'm so beastly cold I don't reckon I could walk a yard without falling down."

"We've got to get back somehow," said Bob grimly. "If we don't we shall jolly well float out to sea. That is, if we don't freeze first."

"Hasn't the other chap gone for a boat?"

"I expect so. But the nearest is at Graystone, two miles up the creek. And then I don't know how they'll ever get here through all this ice."

"And all through my fool fault." As he spoke he tried to scramble to his feet, but was so numb that he slipped back again.

"It is beastly cold," said Bob, who himself was pretty well wet through from lying flat on the slushy ice. "Look here, I'll give you a good rubbing. Then we must take our chance when we get it and try to nip ashore. If we don't we shall simply freeze stiff."

He bent over the stranger and began to rub and pommel him vigorously. The exercise probably warmed him more than his companion, but at any rate it saved them both from being absolutely frostbitten.

Suddenly the floe began to spin rapidly. Bob glanced up and a gasp of dismay escaped him.

"Here's a go! The tide's taken us right out of the pack. How the mischief are we going to get back?"

The other paused a moment before answering.

"You'd better have left me alone," he said quickly. "It was real decent of you to come out after me, but it was no use two being drowned instead of one."

The words were almost the same as those Dan had used, and Bob, looking round, realised that they were pretty likely to come true. Their ice raft was now out in the full run of the tide, and going seawards almost as fast as a man could run. As for getting ashore across the ice, that was out of the question. A squirrel could not have done it. The gaps between the floes were yards instead of feet in width.

"Isn't there any house along the bank—coastguard station or anything of that sort?" asked his companion. Bob shook his head.

"Nothing."

"No boats likely to be out this weather, I reckon?"

"There might be outside, but that's no use to us. There's the bar, you know, at the mouth."

"Rough water, you mean?"

"Always. Enough at any rate to break up a bit of ice like this."

"Then I guess we're gone in?"

Bob set his teeth.

"No—not yet. We may drift back again near the shore. Dan may bring help."

The other boy looked hard at him. He was tall and slight, and had rather a delicate appearance, but there was no flinching in his dark eyes.

"No use of thinking of Dan," he said. "Not if he's got all that way to go first. We'll be on the bar before he can get to Graystone. Say, how much water is there on the bar?"

"Depends on where we strike it. Tide's high still, and it will be out of our depth, unless we strike pretty close inshore."

"I guess we've got to wait. That's all."

While they were talking they were being swept down more and more rapidly. The tide was running a good five knots. They were now a mile below the spot where they had started, and half-way to the bar.

Here the creek was much wider, and there was less risk from other floating ice. All the same they were both kept busy, fending off floes which swung in and threatened to wreck them. And the cold was cruel. Their wet clothes were stiff with ice. Both realised that when the end came they would neither of them have strength to swim.

They watched the bank eagerly as it slid by. But there was not a soul in sight. On all the east coast there was hardly a more desolate spot than the marshes fringing the mouth of Saltern Creek.

They swept round the last bend and the bar was in sight. Bob shivered inwardly. Though the line of surf which broke upon it was narrower than usual, it was filled with fragments of broken floes tossing and crashing together with a low thunder, which sounded terribly near through the clear frosty air.

"Doesn't look healthy," said the second boy. "Wonder if there's any chance of getting through it. There's a craft of some sort out in the bay."

"I'm afraid she's too far off to be any use to us," answered Bob. He turned as he spoke, and stared back up the creek.

"Looking for Dan, eh? I don't guess he can get here in time to help us. Anyway, I doubt if any one would be fool enough to take a boat out in all that ice—except me," he added with a wry grin.

"Not take out a boat!" exclaimed Bob indignantly. "You don't know the marshmen. They wouldn't think twice if it was a case of saving life. They're as plucky a crowd as you'd find in England."

At that moment the floe on which they stood gave a jerk which nearly flung them off. Another much larger, almost a small iceberg, had suddenly crashed into her.

"Quick!" shouted Bob. "Here's our chance." He seized his companion by the arm, and together they made a wild scramble on to the other floe.

"Close call, eh?" said the tall boy as he saw their late refuge ground down and sunk by their new ice raft. "Say, this one's a good three foot out of water. She must draw about eight feet. Maybe she'll ground and give us some sort of a show."

"Let's hope so, anyhow," said Bob as he anxiously watched the surf. They were now terribly near to the inner edge of the broken water. The pounding of the broken floes was deafening.

"If we were only a bit closer in!" he added as he measured with his eyes the distance that separated them from the mud on the right.

"What are we to do?" asked his companion. "Hang on or jump in and chance it?"

"Hang on," answered Bob, "hang on and trust to her grounding. The water's shallow enough inshore, but there's eight or ten feet out here."

As he spoke, the floe came to a sudden stop, then lurched slowly forward.

"Hold on!" shouted Bob, and was just in time to seize his companion and save him from slipping head-long into the broken foam which boiled around them.

"Gosh, I was nearly gone!" gasped the tall stranger as the freezing spray dashed over him.

Bob could not answer. It took all his strength and breath to keep his hold. The small waves were breaking clean over the floe and washing away all the ice which covered it. The stuff below was hard and smooth and slippery. The cold was dreadful. Each wave was a bath of liquid ice. He realised that, within a very few minutes, all their muscles would be numb and paralysed; then they would be swept off and drowned at once.

He twisted his head round so as to get his mouth close to his companion's ear.

"It's no use," he said. "We must make a dash for it. We'll be frozen stiff inside another couple of minutes."

"Just my notion," was the answer, and, in spite of the fact that the speaker was looking into the very jaws of death, his tone was cool and collected as ever.

As he spoke he struggled up on his knees.

"Come on!" he cried. "It's sink or swim, but quick sinking's better than slow freezing."

He fell rather than plunged in, and his head went under at once. But Bob followed and hauled him up, and together they struck out through the breaking waves and churning ice.

It was perhaps sixty yards to the nearest point of the low sandy bank. Before he had gone ten, Bob knew that they would never do it. The tide was dragging them out into rougher water, and the cold was striking to the very marrow of his bones.

He caught a glimpse of the other boy's face beside him. It was white and set.

"I'm done!" he gasped. "Tell dad I—"

A wave washed over his head and cut his words short.

"Hold on—hold up! One minute!"

The voice seemed a long way off, yet Bob recognised it, and, seizing his companion's collar, made a last effort to keep him up and raise his own head above water.

Some one was galloping furiously across the sand on a big horse. It was Dan.

With a rush he came straight into the sea, the water splashing up on either side.

The sight gave Bob fresh strength. Still holding his companion, he managed to get an arm over a floating piece of ice.

Dan had a coil of rope over his arm. He rode on until the horse was almost off his feet.

"Catch it, Master Robert—catch it," he yelled, and flung the rope with all his might towards Bob.

The end dropped almost across Bob's face, and he grasped it with the energy of despair.

"Hold on. I'll get you out," shouted Dan, as he turned his frightened beast towards the shore.

The strain was awful. Bob felt as if he were being pulled in two. But somehow he managed to hang on, and both boys together were drawn steadily through the churning foam and pounding ice, until at last Bob felt firm sand beneath his feet, and still holding the rope, staggered forward to the shore.

"Well done, Dan!" he gasped, and then everything swam before his eyes, and he tumbled flat on his face on the sand.