RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

CLOSE to the opening of a small tent a young man, hardly more than a boy, sat by a dying camp fire. Though his skin was burnt to the colour of an old saddle, his blue eyes and fair hair proclaimed his Saxon blood. Immediately below him a large "batelone" or canoe was moored under the steep bank of a black sluggish stream. In the background a number of Indian peons snored under a rough brush shelter, and behind rose the dark forest, mysterious and impenetrable.

The hot air vibrated with the chirp of crickets, the melancholy bleat of tree frogs, all the strange sounds which go to make up the nocturnal chorus of the hot lands of Lower Bolivia.

In his strong brown fingers the youngster held a string of roughly cut crystals which glittered faintly in the red light of the smouldering embers, and which he was examining with evident interest.

"What have you there, Heron?"

A slight frown crossed Heron's face, as he glanced up at the man who had just come quietly out of the tent.

"Thought you were asleep, Ducloux," he said.

The other, a dark, heavy-set, foreign-looking man, shrugged his shoulders.

"The heat," he said with would-be carelessness; but his eyes, small and black as shoe buttons, were fixed on the string of crystals.

"I believe they are diamonds," said Heron, handing over the stones.

Ducloux almost snatched them.

"Diamonds!" he repealed, and his voice was suddenly sharp. "Where did you get them?"

"The Aguapa cacique gave them to me when I was at the village to-day. I shot a buck for them, and after that, they were ready to do anything for me."

Ducloux kicked the fire into a blaze and bent over it, holding the stones close to the flames. His dark eyes shone more brightly almost than the crystals themselves, as he examined them eagerly.

"Diamonds," he repeated, and there was something like awe in his voice. "You are right, Heron. They are diamonds, Brazilian stones, too, and of as fine a water as I have ever seen. Por Bios, they must be worth a fortune. At least," he went on in a rather less enthusiastic tone, "they would be, were it not for the fact that they are all pierced. What a pity—ah, what a pity!"

"A pity, you say," Heron answered in his quiet, steady voice. "Now to me, Ducloux, that is the most interesting part of the whole business. How, I should like to know, could Indians—savages of the lowest type like these Aguapas—how could they possibly have pierced these stones? Brazilian diamonds are notoriously hard. It would puzzle the cleverest cutter in Amsterdam to bore them like this."

"Bah, they did not do it," returned Ducloux. "This is Inca work, or perhaps that of some even older race. These diamonds are hundreds, possibly thousands, of years old."

Heron nodded, and stretched out his hand for the necklace. "Then you think they are worth something, in spite of the holes through them?" he asked.

"But, yes," declared Ducloux. "In spite of their being poorly cut, in spite of their being pierced, they must be worth thousands."

He leaned forward. "What will you do with them. Heron?" he asked eagerly.

Heron looked at him in momentary surprise.

"That has nothing to do with me. We hand them in to the Syndicate with anything else we pick up, and they will be sold for the benefit of the shareholders."

Ducloux's swarthy brows contracted in a frown.

"But that is very absurd," he answered. "These diamonds are your private property."

Heron shook his head.

"Not a bit of it, Ducloux. Read our agreement with Lechmere, and you will see that all gold or other valuables gathered by us on this expedition are to be handed to him, for sale for the benefit of all the shareholders."

"But that applies only to mineral rights and claims," Ducloux objected. "This necklace you have obtained by private barter."

"I don't look at it that way," replied Heron. "These diamonds go with the rest."

As he spoke he knocked out his pipe on the heel of his boot, slipped the necklace into his pocket and rose to his feet.

"I'm going to turn in," he said. "Good night, Ducloux."

"Good night," answered Ducloux.

Long after Heron had vanished into the tent, Ducloux sat by the fire, rolling one cigarette after another and scowling into the dying embers. Now and then he muttered to himself, but not in English or in French. The words that rose to his lips were in the bastard Portuguese which is the common language of the Upper Amazon.

TWO men thrown together on a journey such as that undertaken by Heron and Ducloux, are as much alone as if cast together on a desert island. True, they had with them eight peons or native carriers, but of these only one, Heron's own man Matias, a mestizo from Manaos, had a word of English. The rest were a cowardly crew, few of whom could be depended upon for a moment in any tight place, and even Matias had the faults of his mixed blood.

If Heron had had his choice he would never have taken a foreigner with him. But in this case the choice had been taken out of his hands. Bob Wilmington, who had been with him on a previous trip, had gone sick at the last minute, and he had had to avail himself of the only man in La Paz who knew the country and was willing to come.

Ducloux called himself a Frenchman, but Heron knew him for a Brazilian, and not a particularly high class one at that.

As he lay in his tent, he could see his companion sitting by the fire, and could make a pretty good guess at his thoughts. He blamed himself for ever having let him see the diamonds, and before he slept he stowed the precious stones in an inner pocket of his coat.

Having taken this precaution he tried to sleep. But sleep would not come. Instead, he felt that dry mouth and throbbing head which means an attack of fever.

He got up, and fumbled for the little medicine chest. He did not strike a light for fear of rousing Ducloux, who was now lying on his cot at the other side of the tent.

But Ducloux apparently was not asleep.

"What is it, Heron?" he asked, sitting up.

"Quinine—that's all," Heron replied. "Where's the medicine chest?"

Ducloux sprang up and struck a match. "What, you have fever! I am sorry. Lie down again. I will get you the quinine."

He was so quick, so evidently anxious to help, that Heron found himself repenting of his previous suspicions. He was so giddy, too, that he was only too glad to drop back on his camp bed.

"Here you are," said Ducloux a moment later, as he handed the other a cigarette paper piled with the familiar feathery crystals. Heron swallowed them at a gulp, washing them down with a glass of water which Ducloux gave him.

"There, if you can sleep you will soon be better." said Ducloux. "Call me if you want anything."

The dose was a stiff one, and sent Heron to sleep with almost magical rapidity.

When he woke again it was broad daylight. His head ached slightly, but he felt on the whole much better. He lay still for a few moments before it occurred to him that the camp was curiously quiet.

"Lazy devils!" he muttered. "I suppose they've taken advantage of my lying abed to have a long sleep."

He sat up, threw off his blanket and rose to his feet. Then, pushing aside the mosquito net which covered the flap of the tent, he looked out.

"Why—what the deuce?" he exclaimed, roused for once out of his ordinary calm.

His surprise was not unnatural. Of Ducloux and the peons there was no sign at all, while of the whole camp the tent in which he had slept was the only remaining portion.

He made half a dozen hasty strides in the direction of the river. The canoe was gone. Then suddenly he thrust his hand into the inner pocket of his coat.

It came our empty.

"The darned thief!" he said quietly.

Now the whole thing was clear. The diamond necklace had been too great a temptation for Ducloux. He had drugged and robbed his companion, stolen the boat, and gone off. By this time he was no doubt miles away down stream.

FOR a moment or two Heron stood quite still. By the frown on his forehead he was evidently thinking hard. Then, turning sharply, he went back to the tent and began to investigate.

The result of his search was not encouraging. Ducloux had done his job thoroughly. Barring half a dozen small tins of tongue and similar delicacies which happened to be in the tent, and a little sugar and coffee, he had gone off with all the stores. He had also taken all the firearms except Heron's heavy rifle, which, together with about a score of cartridges, had been lying under its owner's cot.

"Serves me right for trusting an infernal Dago," said Heron with a wry smile. He took a map from his pocket and began to study it.

"Cochamba—that's the nearest approach to civilisation," he remarked presently. "And Cochamba's a hundred and sixty miles away. Well, the odds are all against me, but I've got to try it."

Heron had been in tight places before, but was quite aware that this was a long way the tightest. He was in country where five miles was a big day's march. Even supposing he were not scuppered by savages, snakes, or wild animals, it would take nearly a month to get to Cochamba, and he had food for a week at the very outside.

He was perfectly calm about it, and began deliberately to pack up. The tent, of course, he would have to leave, but be must take his food, medicine, rifle, blanket, and mosquito net.

The package was of formidable size, and he was looking at it in dismay, when a shadow fell across him, and he started up, grasping his rifle.

"Do not shoot, seņor," came a quick voice, and, to his amazement, there was Matias, the mestizo, and with him one of the peons, a big, muscular, stupid-looking fellow named Pablo.

"So you thought better of it?" said Heron rather grimly.

"We would not go with the Seņor Ducloux," explained Matias. "We saw him loading up the boat, and we were afraid and hid among the trees."

Heron looked at him with some contempt.

"Why didn't you wake me, you idiot?"

"We were afraid," repeated Matias, and that was all that Heron could get out of him.

All the same, though he did not show it, Heron was grateful that he was not quite abandoned, and began hastily to revise his plans. Matias and Pablo had their axes, and this gave him the idea that it might be possible to build a raft and continue the journey by water. The distance would be greater, but they could cover it much more rapidly.

He mooted the plan to Matias, only to find the man seemed singularly loath to agree.

"But what's the objection?" demanded Heron impatiently. "We were going down the river in any case. Man alive! you don't want to walk, do you?"

He could get nothing out of Matias. The half-breed merely looked frightened and stupid. Eventually, however, he agreed, and the three set to work at once. There was plenty of material available, and by midday they had completed a good-sized raft of the sort known in the country as a "callapo."

Two rough paddles and a punt pole completed their equipment, and as soon as they had loaded up they started.

Food was the main question. For the three of them they had barely enough for two days. Heron kept his eyes on the banks, looking out sharply for any sort of game.

On most rivers there would be plenty—deer, monkeys, tapirs, agouti, peccaries. Here, there seemed to be nothing. The creatures of the wild knew as well as Heron himself that the water of this foul stream was not fit to drink. All that afternoon they saw no living thing but birds, and you cannot shoot birds with a .38 express rifle.

If Heron had had any notion of catching up with Ducloux, that was gone before nightfall. The batelone was slow enough, but the raft crawled. However, it was better than the swamps, and for that he was grateful.

They found fresh water for their camping ground, made a slim supper, and were off again at dawn.

That day the river began to get on Heron's nerves. Hunger and anxiety may have had something to do with it, but to him it seemed that this black, crawling stream had become an actual enemy. The long, lifeless stretches, with the everlasting forest walling it in on either side, the thick, dark water so tainted with iron as to be almost poisonous, the muddy banks where the hideous crocodiles lay silently watching from under their horny eyelids, the utter silence, and the brooding, almost intolerable heat!

And, as before, there was no game, and Heron grew more anxious with every hour that passed.

"What do you call this river?" he asked at last of Matias, more because he longed to break the silence than for any desire to know. It had no name on any map.

Matias hesitated.

"El Rio de las Animas Perdidas," he said at last in a low voice.

"River of Lost Souls. Cheerful title! But, upon my word, it suits it. Why do you call it that?"

"Because, seņor, no one has ever reached its mouth," was the man's curious reply.

Heron opened his eyes.

"I should not have thought that anyone had over tried to," he answered.

"But they have, seņor. It was down this river that Santonia led his expedition to find the Inca gold. Eighty men he had, and not one ever seen again. Henriquez Dominico, he tried to pass down this stream with a great fleet of batelones. They perished. Others, too, in the old time when the Spaniards ruled the land."

"If they failed, we've got a fat chance," thought Heron. Aloud, be said, "And what about ourselves. Matias?"

The half-breed crossed himself. "It is in the hands of the Saints," he said fatalistically.

Towards afternoon the river grew so narrow that the branches of the gigantic trees on either side actually met overhead. Creepers thick as ships' cables connected them, and the sky was shut out, so that the party on the raft seemed to be toiling forward at the bottom of a vast, green tunnel.

Drowsy with the breathless heat, Heron was paddling mechanically, when a cry from Matias startled him.

The man was standing with outstretched arm, and a look of absolute terror on his brown face.

"The batelone!" he muttered hoarsely. "The batelone!"

And, following the direction of the pointing hand, Heron saw the big canoe lying wedged in a patch of water weed under the left-hand bank. She was tilted partly over and apparently half full of water.

Of Ducloux or the rest of the crew there was absolutely no sign at all.

IT was some seconds before anyone spoke. Then Heron broke the silence.

"Where the deuce are they?" he asked amazedly.

Matias shrugged his shoulders.

"It is as I said, seņor."

"You mean they've gone the way of the rest," said Heron impatiently. "Yes, but how? They certainly didn't land here, for there's nothing but swamp on both sides. Equally surely, they didn't commit suicide. Something must have attacked them. Push the raft up, and let us see."

The mestizo hesitated Clearly he was badly scared. Heron, wielding his paddle with all his force, turned the heavy raft in towards the bank.

It drove soggily into the mass of weed. A foul odour from the decaying mass tainted the stagnant air, and a cloud of carrion flies arose. Pablo, the Indian, gave a hoarse cry of terror.

Small wonder, for fast in the tangled weed lay the bodies of two of his former companions, bloated and horrible.

"Ugh!" muttered Heron between horror and disgust. Matias dropped back, his dark face ashy with fright.

"Pull yourself together, man," said Heron sharply. "We must get hold of the batelone. She is not much damaged, and there are still stores in her."

It took all his energy to force his two frightened followers to the work. But, between them, they did at last succeed in baling out the big canoe and extricating her from the weed.

Those two bodies were the only ones in sight. The rest, including Ducloux, had vanished. The batelone herself was apparently little damaged, but Heron noticed that in one place the gunwale was crushed, as though some great weight had dropped upon it.

The stores were still in her, and as most were in water-tight cases, still undamaged. In spite of everything, Heron's spirits rose. The ghastly prospect of slow starvation was, at any rate, ended.

He tried to make Matias realise their good fortune, but quite failed. The man was sunk in an abyss of superstitious terror. Clearly he looked upon himself and the others as doomed.

At last they were clear, and had left the ill-omened spot behind. Heron made up his mind to stop as soon as he could find a place to land, and light a fire and cook a good meal. It would do them all a world of good.

But there was no landing place in sight. Instead, the ugly river narrowed still more, with walls of lush green vegetation penning them in on either side. The heat was insufferable, and Heron's throat was dry as dust.

A couple of hundred yards below the spot where they had found the balelone the sluggish river curved to the left, and as they rounded the bend Heron saw, to his disgust, that a dead tree had fallen across the stream, spanning it from bank to bank.

Disgust, because it barred the passage, and would have to be cut through before they could proceed. And well he knew by previous experience the difficulties and dangers of such a task.

The great log lay level with the water, and against it had drifted a mass of debris which hid the surface of the scummy stream. This stuff had formed a wide raft which was covered with a perfect jungle of water weeds. Tall white heads of water celery rose six feet or more, and lower gleamed the heavenly blue of the water hyacinth.

The tangle had a tropical beauty of its own, but Heron thought not of the flowers, but of the stinging insects and deadly water vipers which lurked among the blooms.

He stopped paddling, and the batelone drifted slowly towards the log.

"We must cut the tree, Matias. There's nothing else for it," he said gloomily.

He got no reply, and, turning in surprise, saw the man huddled in the stern, grey and shaking with terror.

"What the deuce—?" he began angrily. The words were cut short by a sound like the escape of steam from a locomotive.

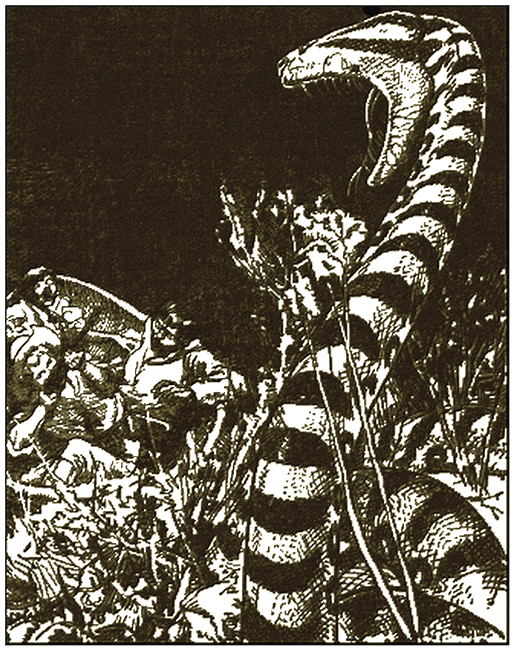

Before his amazed eyes, a head rose out of the tangle, a head two feet in length, and raised upon a neck nearly as thick as his thigh. The mouth was open, and a forked tongue darted in and out between white fangs that must have been full six inches in length. Most terrible of all were the eyes—long, narrow, unwinking, the colour of clear amber.

Heron had seen snakes of all sorts and sizes, but never in his wildest dreams had he imagined a monster such as this. Judging by the size of its head, it looked to be between sixty and seventy feet long*, and to weigh a couple of tons.

(* A snake of this size was killed by Colonel Fawcett, R.A., who gave an account of his journey in Bolivia before the Royal Geographical Society.)

For a moment horror held him spellbound. He could not speak, he could hardly breathe.

Slowly—very slowly—the monstrous head rose higher out of the flowery jungle. It began to wave slowly to and fro. With a wrench, Heron dragged his fascinated gaze away from those awful eyes, and, stooping, picked up his heavy rifle.

"Do not shoot! For the love of Heaven, seņor, do not shoot!"

In an agony of fright Matias had actually seized him by the arm.

Heron shook off the man roughly.

"Don't be a fool," he said curtly. "How are we going to pass unless we kill the brute?"

"He will kill us all," replied Matias with the certainty of despair. He dropped back, and he and Pablo lay crouching in the bottom of the boat, their lips moving soundlessly as they repeated their last prayers.

"Just as well," muttered Heron, and raised the rifle to his shoulder.

He knew the risk as well as they did—knew that if he did not finish the business with one shot, he would get no chance of a second. The anaconda, the huge water python of South America, is by far the most aggressive of his tribe, and the great, dint in the side of the canoe and the fate of its previous occupants no longer needed explanation.

The vast head was now ten feet above the reeds. Its owner was making ready to attack. Yet Heron, finger on trigger, had leisure to notice with a certain grim satisfaction that his hand was perfectly steady. He was one of those men whose nerves tighten in a real emergency.

The vast head was now ten feet above the reeds.

He waited no longer, but, taking careful aim at those unwinking, deadly eyes, pulled the trigger.

The report of the rifle echoed like a cannon shot up and down the long aisles of greenery. The great head went back as though driven by a ram, and suddenly, coil upon coil, the vast body rose, writhing, out of the brake.

"Back!" roared Heron. "Back for your lives!"

Pablo snatched up a paddle; Heron, dropping his rifle, seized another, and, between them, they forced the canoe back.

Just in time. Next moment it was as if a tornado had struck the stream. The monster's death agony flattened the tall growth like grass, and beat the dead river into waves which nearly swamped the canoe. The air was full of broken vegetation and yellow spray. Even Heron was appalled by the chaotic struggles.

They ceased at last, and the shining column lay out all across the log as motionless as the wood beneath it. Heron drew a long breath.

"That's the end of your bogy, Matias," he said with a smile. "No more lost souls down this river."

"And yet," he added, " I'm half sorry I had to kill the beast. After all, he did us a good turn."

"If you had not, seņor, we should have died like the others," replied Matias with absolute conviction.

Heron looked thoughtfully first at the man, then at the serpent.

"What became of them, I wonder," he said. "Are they all at the bottom of the creek?"

"Not all, seņor. The serpent had eaten one. He had eaten lately or he would have attacked us before we came so near."

Heron considered a moment. He looked at the cases of stores. At any rate, the food question was solved, and there was no longer the same desperate need for haste. And there was the chance—just the chance that he might recover the diamonds.

The stones were there.

"Now for the axes," he said.

An hour later, the grisly horror on the dead trunk passed out of sight. Heron drew a deep sigh of relief, and a slight smile played across his thin face.

But he was not thinking of the diamonds. His eyes were on the anaconda's head, which lay in the stern of the boat, with its three-inch fangs gleaming in the sun.

"That's proof," he said to himself. "They can't accuse me of travellers' tales with that before their eyes."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.