RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library.

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

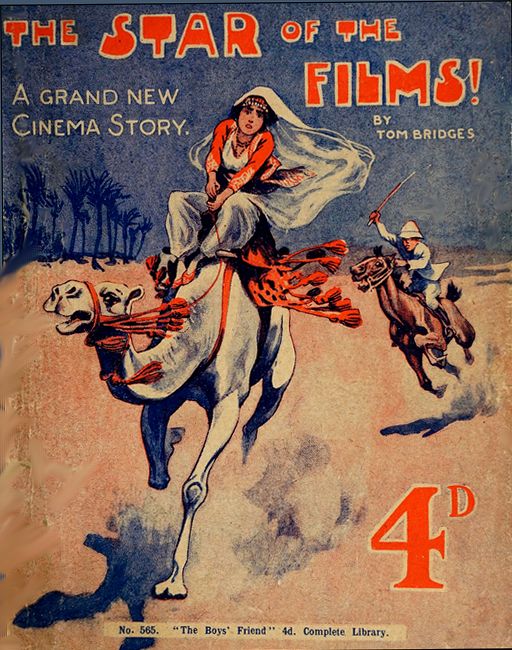

Boys' Friend Library, #565, July 1921

"LOOK at that, Reggie! Did you ever see the like?"

Reggie Dacre, an extraordinarily good-looking young fellow, glanced in direction indicated.

"That—ah—boy," he drawled, "the—ah—infant who appears to be amusing the—ah—congregation of coffee-coloured gentleman. Is that what you mean, Joe?"

"Of course it's what I mean!" replied big Joe Fosdyke, pulling up and staring at the boy in question. "Do you mean you don't see anything funny about it, Reggie?"

"I—ah—perceive that the boy has blue eyes, and hair of a somewhat lighter than that of his audience."

A grin spread across Joe's big, red face.

"You've got eyes, Reggie, though you don't always use 'em. Yes, that kid's white."

"'Was,' you should say," corrected Reggie gently. "At—ah—present his complexion is—ah—dreadful. It is plain that he has taken, no precautions whatever against this—ah—abominable Egyptian sun."

Joe grinned again.

"He ought to take a leaf out of your book, Reggie," he said, as he glanced at his companion's white buckskin gloves, his broad-rimmed white helmet, and green-lined umbrella which he carried.

"Joking apart, Reggie," he went on, "that kid interests me. I believe he's English. But what brings an English boy telling stories in their own language to a parcel of niggers in a Cairo bazaar? Tell me that!"

"It's too hot to answer riddles, old bean," replied Reggie plaintively. "But—ah—I admit that the youth has his points. He—ah—registers his emotions extremely well."

"Just what struck me," said big Joe rapidly. "Though I don't understand a word he says I can almost follow the story by his face. There, he's just getting to the curtain this minute."

The boy—he was about fifteen—was sitting cross-legged on a big packing-case under a gaily-striped awning, and the score or so of brown men who formed his audience were hanging on every word he spoke. Their eyes wen fixed upon his face, and some were quite breathless with excitement.

"Only wish I could understand the lingo," said big Joe almost pettishly.

At this moment he was interrupted by a deep voice from behind.

"Come on, Fosdyke! We can't stick here all day. We shall he late for dinner if we don't get a move on."

The speaker was a man of Fosdyke's height, but not so heavily built. There was strength, brutal strength in every inch of him, from his long, narrow feet to his cold, pale blue eyes. Luke Carney had once been lion-tamer in Barnum and Bailey's big show. Now he was a member of Joe Fosdyke's Golden Apple Film Company.

"I'm interested in that kid, Luke," said Joe. "Watch his face. See how he patters that lingo. I've a mind to wait till he's finished his yarn, and have a chat with him."

Before any one of the three could speak again, there was a sudden roar in the distance. An unpleasant—indeed, a terrifying sound. It was a shout from many throats mingled with the rush and trampling of hundreds of feet.

As if by magic, the little crowd that had been listening to the boy melted away and vanished.

Joe Fosdyke felt a touch on his arm. The boy stood beside him.

"Clear out!" he said urgently.

"Why, what's the matter, sonny?" asked Fosdyke.

"A riot!" the boy answered quickly. "The students are at it again. Every budmash in Cairo will be with them. Hook it for all you're worth, if you don't want to be killed!"

Fosdyke stared.

"Killed!" he repeated. "But we're British, and Cairo's a British town."

"Oh, is it?" returned the boy with scorn. "If you'd been here as long as I, you'd know better."

He changed his tone.

"Please go! I give you my word there's bad trouble afoot!"

Luke Carney cut in.

"Bah, the brats crazy! It's only some nigger-celebration. Mean to say you're going to let this ragamuffin scare you, Fosdyke? I'd be ashamed."

The boy swung round on him.

"Stay, if you want to," he snapped. "There won't be many mourners at your funeral! Mr. Fosdyke, please come!"

All this time the roar had been growing louder and more threatening. The sound was coming nearer. Now, just as Fosdyke and Reggie were getting ready to move, a mob of men swept into the head of the street, barely a hundred yards away.

They were a wild-looking lot, all armed with sticks or great clubs, and stones, and were led by a couple of hideous-looking, long-haired, greasy ruffians.

"Ingreezi! Ingreezi!" they yelled, as they caught sight of the white men. "Kill the Ingreezi!"

"About time we made a move," suggested Reggie in his soft voice, but the colour faded out of Carney's blotched face.

The boy caught Joe by the sleeve.

"This way!" he said urgently. "Follow me!"

He darted off, and this time none of them hesitated about following. Straight down the street went the boy, and the way he legged it was surprising. Reggie kept up easily enough, but Joe Fosdyke was panting. The crowd, roaring vengeance, swept in pursuit.

Quick as a cat, the boy nipped sharp round to the left, under an archway. The three men pounding at his heels found themselves in an alley no more than six feet wide, with high walls on either side.

"A trap! The young fool has led us into a trap!" snarled Carney in Joe's ear. "See! It's a blind alley!"

Sure enough, the alley ended in a blank wall. Joe's heart sank. After all, he knew nothing of the boy who might very well be in league with the mob of rioters.

He sprinted, caught the boy, and seized him roughly by the shoulder.

"Where are you taking us?" he demanded hoarsely.

"To safety!" snapped back the boy. "Hurry! They'll beat us to death if they catch us. They're mad with opium, and crazy against the Government."

Joe saw they had no choice but to trust their guide. He released the boy, who led him on rapidly to the end of the alley.

In the wall was a narrow door, ancient and clamped with heavy bars of iron. The boy rapped on it twice, then a pause and a third single rap.

He stood waiting. By this time the first of the rioters were in the alley. Their yells were bloodcurdling.

Joe Fosdyke's heart thumped against his ribs, even Reggie was a little pale. Carney's face was livid. He was snarling threats against the boy under his breath.

A clank, as of a chain falling, the creak of a key in the wards of the rusty lock. Suddenly the door swung back, and as the four went tumbling inwards, it slammed to again with a heavy crash.

From outside came a yell of disappointed fury, and Joe waited breathless, expecting to hear the thud of the attack.

Nothing of the kind happened. A yell or two, then a rush of feet. After that, silence.

Joe turned surprised eyes upon the black. The boy laughed.

"You're quite safe," he said. "Even the worst budmash in Cairo would think twice before attacking the tomb of Sheik Selim."

VERY gravely Reggie Dacre took off his right glove, and extended his hand to his rescuer.

"I owe you a thousand apologies, my friend, besides my grateful thanks. I—ah—confess that for a moment I came to sharing the apprehensions of our lion roaming friend."

The boy shook hands quite gravely.

"I don't wonder," he said, "Of course, you didn't know me!"

"I trust," Reggie answered, "that our acquaintance may improve."

"That's what I say, son," added Joe Fosdyke heartily. "If I'm not very mistaken, you've saved the lives of all three of us. What's your name?"

"Phillip Fernie," was the answer.

"English?" questioned Joe.

"Yes, sir! My father and mother were both English." His keen, young face went very grave. "They are both dead," he added.

Joe looked at him keenly.

"You don't mean to say you are on your own, Fernie?"

Phil nodded.

"I've lived in Egypt most of my life. You see, I talk the language, and I get on somehow."

"Tough!" said Joe briefly. "If it's not a rude question; what do you do for a living?"

"Tell stories. And sometimes I write letters for my friends. Some of them are very good to me."

Joe shook his head.

"Not much of a life for a white man," he said. "Hasn't it ever struck, you to get a better job?"

"Often, But what could I do? The only white people here are the Government officials and the soldiers. They've got nothing for me."

"But I have," said Joe. "See here. I'm manager of a film company, and we're going out into the desert to do a big picture. I reckon I can find you a job. Are you on?"

Phil's face lit up.

"I should think I was!"

"Good! You come right along with us to Paster's Hotel, and I'll fix you up straight off."

Phil hesitated.

"May I go home first, sir?" he asked. "I'd like to say good bye to old Achmed, the man I've been living with. I'll come in the morning."

"Go anywhere you've a mind to so long as you turn up all right," said Joe heartily.

"But you're not going to abandon us, Fernie," said Reggie plaintively. "We don't wish to waste the rest of our young lives on this sacred ground. And there's the black gentleman who opened the gate for us, and is watching us with a reproachful eye. I think he's looking for a tip, be."

Joe forked out a handful of silver, and gave the negro such a tip as made his eyes bulge.

Phil looked reproachful.

"You shouldn't have given him all that, Mr. Fosdyke," he said. "It's enough to keep him for six months."

Joe laughed.

"He's earned it, and hadn't you better take a dollar or two yourself, young 'un? You'll need money to settle your bill for lodgings."

Phil flushed a little.

"Thank you, sir! I have enough for that. I'll wait for my money till I've earned it! Now I'll show you the way out."

There was a gate at the far end of the enclosure. He led them through this, and by a (line) of narrow lanes into a broad street.

"You'll be all right now," he said, and with a bow that would have done credit to a duke, took his departure.

Reggie watched him hurrying away.

"I think you have a find there, Joe," he said quietly, as he opened his umbrella.

"I'm right down sure of it," replied Fosdyke heartily.

Luke Carney said nothing, but the expression on his hard face augured ill for the newest recruit to the Golden Apple Film Company.

Twenty minutes after Phil had left them, the three were safe back in Paster's Hotel, and Carney went straight to his room.

Lounging in a lounge chair by the open window, was a youth of sixteen, a cub, with just the same narrow and blue eyes and thin lips as Fosdyke himself.

He looked up as Luke entered, and his eyes widened slightly.

"What's up, father?" he asked.

"The matter!" snarled Luke. Then suddenly he quieted down, and, taking a chair opposite his son, lit a cigar, and began to talk.

The boy listened, and though now and then his dull eyes glistened oddly, he said nothing.

"So you see, Paul," ended the eider man, "the first thing to do is to get rid of that brat. He's not to come with us. Somehow or other we've got to stop it."

Paul nodded.

"We'll do that," he said, "but remember you can't stop Dacre."

Luke's lips curled.

"Don't worry about that dude. I'll find my chance to handle him, and when I've done with him his own mother won't know him. For the present it's this fellow, Fernie, we've got to think of. Something tells me he's dangerous to us, and to our plans."

"To our plans?" repeated Paul, sitting up straight. "What can he know about them?"

"Didn't I tell you his name was Fernie?" demanded Luke.

Paul whistled softly.

"It didn't strike me at first. But you're right. Of course you're right!"

The dinner-gong, warning brazenly below, cut short their conversation. They got up and went down together.

Next morning dawned brilliant and cloudless, as usual, and it was not yet seven when the Golden Apple Company sat at breakfast in the big, cool dining-room of the hotel.

Joe was hurrying them up. It was their last day in Cairo, and they had a scene to do that morning in the hotel courtyard.

As the company trooped out to their dressing-rooms, Joe called a waiter.

"Send O'Hara to me!" he told him.

A minute later steps pattered along the veranda, and a boy came hurrying in. A boy so short he was almost a dwarf, yet sturdily and compactly built. He had the reddest hair, the widest grin, and the broadest brogue that ever came out of Ireland, and his name was Leslie O'Hara.

"Les," said the manager, "I'm expecting a new hand this morning, and I want you to look out for him. His name is—"

"Phil Fernie, sorr," cut in Les, with a twinkle in his eyes.

"How do you know that, you scamp?"

"Haven't I ears, sorr, and other folk has tongues?"

"Your ears are too long," said Joe, tweaking one of them. "Well, go ahead and meet him. If he hasn't had breakfast, give him some. Be good to him, for he's a smart fellow, and I like him."

"It's more than some do!" remarked Les, but he spoke below his breath, and the manager, who was on his way out, did not hear.

Half an hour later work was in full swing outside. A party of explorers, mounted on donkeys, were filing before the camera, and Joe, up to his neck in it, had forgotten everything else under the sun except his play.

Of course there was a hitch. There always is just, at the critical moment. This one was caused by a camel.

The play, to film which Joe Fosdyke had brought his whole company to Egypt, was called "The Witch of the Desert," and at great expense Joe had secured the services of the great French film-actress, Zolie de Chartres, to take the star part of the witch. In the first act Zolie had to appear mounted on a camel, and meeting the travellers from the hotel, warn them solemnly against the treasure-hunting expedition in which they were supposed to be engaged.

A special camel had been procured—a beautiful, white creature of the true Bedouin strain—but the Egyptian who had brought it did not seem able to manage it, and the brute refused to kneel for the lady to mount.

Luke Carney was not on the spot, but Paul, who fancied himself as a handler of animals, was there. In his hand he carried a handsome, silver mounted riding-whip.

"Get down, you brute!" he cried angrily, flicking his whip at the tall beast's legs. "Get down, I tell you!"

"'Ee vill not lie down. 'Ee was naughty!" exclaimed mademoiselle in her high-pitched, broken English. "Eet is no good, I tell you. Ve vill 'ave to get anozzer camel!"

"Nonsense!" exclaimed Joe impatiently. "We couldn't find a finer beast in Egypt. The trouble is these fellows don't understand how to manage the brute. You don't seem able to do much, Paul."

Paul's dull eyes flashed. He was furious at the slight on his powers. And all the more because he caught the amused smile on Reggie's good-looking face. He made a dive at the camel, caught hold of one of its front legs, and tried to lift it.

Now, a camel at best is a queer-tempered beast, and these one-humped, racing camels are notoriously ugly. Without the slightest warning the brute bared its teeth and struck downwards like a snake.

But instead of getting hold of Paul, its yellow teeth closed upon the shoulder of Mademoiselle de Chartres, and plucked her clean off her feet.

The scream of terror rang out high and sharp, echoing back from the walls of the courtyard, and in an instant all was confusion.

In a flash Reggie was off his donkey, and had dashed forward. Joe, too, made a rush but the trouble was that neither of them had the faintest idea of what to do.

Like a shot from a gun, a slim, active figure, dressed in native costume, came racing through the terrified crowd, and Paul Carney, who had staggered back, as much at a loss as the rest of them, felt, his whip snatched from his hand.

Quick as thought the new-comer leaped at the camel, and brought the whip across its nose with stinging force.

With a bubbling cry of rage the camel opened its mouth, dropping mademoiselle, and Joe, catching her as she fell, whirled her aside.

Only just in time, for down darted the long, snake-like neck, and some of the women screamed again as they saw it strike straight at mademoiselle's rescuer.

Before those great, yellow fangs reached him. Phil had leaped back out of reach, and down came the whip again across the camel's face, with a crack like a pistol-shot.

So fierce was the blow that the whip snapped clean in half, but it had done its work. The camel, completely dazed, was swaying its head stupidly from one side to another.

Phil never moved. He stood in front of it, and spoke to it in fluent Egyptian. Then, the utter amazement of the entire company, the creature dropped quietly down on its knees, and remained there patient and motionless.

"Bravo, Fernie!" cried Reggie Dacre. "Bravo, youngster!" echoed the others.

"Is the lady hurt?" asked Phil anxiously.

Mademoiselle answered for herself.

"I am not hurt, any zing to seegnify," she announced bravely. "It ees my cloak that ze camel did catch viz his teeth. Keep 'im on ze knees, mon brave garcon, and I vill show him I do not fear him."

Joe begged her to wait and rest, but she would not hear of it, so he helped her into the saddle.

Phil spoke to the camel again, and the creature rose obediently, and with Phil leading it, walked quietly round the yard.

"He won't give any more trouble now," said Phil calmly.

"H'm! I wouldn't trust him unless you were here to handle him," growled Joe. "This will be your job, Phil, and you'll get three quid a week, and all found. That suit you?"

Phil's eyes were full of gratitude.

"It's most frightfully good of you, Mr. Fosdyke," he answered. "I only hope I can make myself worth it!"

The rehearsal went on then the scene played and photographed. In a little more than hour it was all finished.

Joe beckoned to Les O'Hara.

"Les, take Fernie round to Mrs. Merry, the wardrobe-keeper, and ask her if she can fit him up in a suit of reach-me-downs. He must have some English clothes."

"Right, sorr!" replied Les, with his cheery grin.

But when he looked Phil was no longer in the courtyard.

"He'll be taking the ould camel round," said Les to himself, and made through an archway for the stables.

Sure enough, there was Phil in the yard. He was sponging the blood from the camel's cut nose.

Before Les could hail him another figure appeared. It was Paul Carney.

He walked straight up to Phil.

"You think yourself clever," he said, with a sneer. "You've got round old Joe all right, but let me tell you, you won't get round me so easily."

Phil looked up.

"I shouldn't dream of trying to," he answered gently.

Les stood where he was.

"Sure, this fellow knows how to take care of himself," he chuckled. "I'll just be waiting and see what'll happen!"

Paul glared. He did not quite know what Phil meant, or how to take his remark. He changed his tactics.

"What are you going to do about my whip," he blustered.

"The one I broke over the camel? Oh, I dare say that Mr. Fosdyke will pay you for that. If not, I shall be happy to buy you a new one out of my first week's salary."

Phil's voice and manner were perfectly quiet and self-possessed. His refusal to take offence made Paul simply furious.

"If you think that a pauper brat like you is coming butting in here, doing the high and mighty, let me tell you you're precious well mistaken!" he burst out.

Phil stared at the other a moment, then broke into a merry peal of laughter.

This put the hat on it. Paul rushed him, slogging violently.

PAUL was three inches taller than Phil, and a stone heavier. The grin faded from the face of Les, and he dashed forward.

Before he could reach the scene of the combat he had stopped again.

"It's a fool I am!" he said softly. "Phil's a match for him. Wait now!"

He had not long to wait. A boy like Phil, who had spent years in a place like Cairo, was up to every known trick of rough-and-tumble, and to a good many quite unknown in England. Never in his life had that young bully—Paul Carney—made a worse blunder than in his wanton attack on Phil Fernie.

It was all so quick that Les's astonished eyes could hardly follow what was happening. He saw Phil duck, and Paul's flashing fists pass harmlessly over his head. Next, he saw Phil's arms clasped around Paul's knees. Then, in some mysterious way, Paul was going up into the air as if shot off the end of a spring-board.

An Egyptian stable-yard is not like an English. It resembles an old type of farmyard, only is much dirtier. Paul came down, head foremost, into a pile of wet, ill-smelling filth, and lay there floundering helplessly. His whole head and shoulders were actually buried in the gruesome mess, and he would quite likely have suffocated if Phil had not caught him by the legs, and hauled him out.

Paul lay gasping like a fish out of water. Phil stood over him.

"I'm sorry," he said calmly, "but really you brought it on yourself."

Paul rose slowly to his feet. Under the filth that covered it, his face was white as paper. He was quivering all over. For a few seconds he stood glaring balefully at Phil, then, without a word, he turned and walked away.

"Sorry, is it?" exclaimed Les, coming up. "Sorry, begad! Sure, I niver was more plazed in the whole of me life!"

Phil shrugged his shoulders.

"I hate making enemies," he said.

"Ye needn't trouble," said Les dryly. "That fellow was your enemy before iver he set eyes on ye! He's the son of his father, and now ye'll understand. Now, come on wid ye," he added. "The boss says ye are to have new clothes."

At lunch-time the order went forth that the party were to pack, ready for an early start next day.

A cinema film company has to carry a lot of props, and all the junior members are expected to make themselves useful in the way of getting things together.

Les took Phil in hand, and led him down to a big store-room in the basement, where he set him to work, and showed him what to do.

"Meself, I've to go down to the river, and see if the boat's ready," he said. "I'll be finding ye here when I come back."

It was fairly cool down, here in this underground place, and Phil, who was very happy is his new job, whistled softly as he stowed away packages of all sorts in big wicker baskets.

He had been at it for about half an hour when some footsteps on the bare stone floor made him look up. Paul Carney was coming in.

Instinctively Phil stiffened, and stood watching his enemy in silence.

Imagine his amazement when Paul came across with outstretched hand.

"Fernie," he said, "I lost my temper this morning, and behaved like a brute. I want to say that I am very sorry."

Phil was so flabbergasted he could find no words.

Of anything that could happen this seemed the most wildly unlikely.

"Will you let bygones be bygones," continued Paul, "and shake hands?"

Phil pulled himself together.

"Why, of course I will," he replied cordially, as he took Paul's hand. "There's nothing I hate more than rows, and particularly with people in the same show. I'm only sorry I threw you so badly this morning."

That queer gleam showed for a fleeting instant in Paul Carney's curious, dull-blue eyes, but he grasped Phil's hand firmly, and shook it hard.

"That's the way I feel about it," he said. "And, anyhow, I deserved all I got. Now, I'll give you a hand if you'll let me."

He set to work with a will, and very soon all the packages were safe in their baskets.

But the baskets were not full.

"There's more stuff in the inner cellar," said Paul. "We'd best get that."

He led the way. This inner cellar was a great, dark, echoing place, and as Paul switched on the light, Phil saw that all sorts of rubbish was piled there.

They collected and packed the rest of the stuff. Paul talked all the time, asking questions about the country, and Phil, pleased to find him so interested, told him a story or two of some of the queer places in Cairo.

"You have seen a lot," said Paul enviously, as they strapped up the last of the baskets. "Before we go up I must have a look round that inner cellar. There might be a trapdoor or something."

He went back, and Phil stood waiting for him. Phil was really pleased that Paul had turned out decent after all. He had spoken quite truly when he said that he hated rows.

"Fernie, the floor sounds hollow!" came Paul's voice from within. "I say, have you got any matches? I do believe there's a trap or something here."

"Yes, I've got some matches," Phil answered, as he followed Paul.

He found him standing near the far side of the big underground place, almost beyond the ring of light flung by the single electric-globe.

As Phil went across, it struck him that the air had a sort of damp, chilly feeling, in curious contrast to the blazing heat up above.

"It's hollow all right," declared Paul, stamping on the floor. "I say, I wonder if it's true that there really are other cellars below this."

"It's likely enough," said Phil, as he struck a match. "Yes, you're right, Carney. There's a hollow of some sort below. Ah, and here's a trap! See, this stone has a ring in it. Can you see it? It's almost hidden by dust!"

"I can see it all right," declared Paul. "I say, do you think it would come up?"

He stooped, got hold of the ring with both hands, and tugged.

"It's shifting," he panted. "Lend us a hand, Fernie!"

Phil was mildly amused at the other's excitement. He could not see much point in prizing the big flagstone, but he wanted to be friendly so laid hold of the ring.

With a creak, and a groan the big flagstone came out of its bed, and a black chasm yawned in the floor.

"Another match—quick!" said Paul. He was so excited that his fingers shook as he struck it. He held it over the hole.

"What luck! There's a ladder! I say, Fernie, let's go down."

"Thanks," said Phil, with a laugh. "You don't catch me risking my neck on the rungs of a rotten old thing like that!"

"It looks all right," declared Paul, holding the match down at arm's length. "Wait! I've got a bit of candle in my pocket."

He pulled out a candle end, and lit it, and examined the ladder more carefully.

"I'm sure it's sound," he vowed. "Hold the candle, Fernie. I'm going to try.

"There, I told you so. Sound as a bell," he continued. "I'm going down."

He took the candle and went slowly downwards.

"Look out for bad air," Phil warned him. "There's a queer, musty smell comes up from below."

"All right," said Paul, "I'll watch out."

Step by step he went down, while Phil watched rather anxiously.

"The fellow's crazy about this cellar," he grumbled. "I only hope the ladder holds."

All in a moment his worst fears were realised. There was a sharp snapping sound, a yell, a thud. The light went out.

"Are you hurt?" cried Phil sharply.

There was no reply.

"The idiot! I ought to have stopped him," he muttered, and, lighting a match, started downwards.

The ladder seemed sound enough, and Phil tested each rung carefully before he put his weight on it. Presently he found a gap where two rungs had broken clean away. But those below were firm, and in another minute he was at the bottom.

His match had gone out. He paused an instant to strike another. As he did so, he thought he heard a slight rustle. He turned quickly.

The movement saved his life, for a vicious blow from a life-preserver missed his head, yet fell upon his shoulder with such force as numbed his whole arm, and sent him reeling to the floor.

Next instant a figure leapt across him, and went rattling up the ladder towards the square of light overhead.

Dazed and sick, Phil struggled to his feet, and started after. But his right arm was useless. He could only crawl slowly upwards.

From above came an ugly laugh.

"Too easy!" sneered Paul.

Down crashed the great stone into its bed, and Phil was left alone in pitch darkness, and in a silence that was like that of a tomb.

Trapped as he was, most boys would have lost their heads, and raved and shrieked. Some would even have gone mad with sheer terror.

Phil was the exception. Short as his life had been, this was by no means the first time he had been in a tight place, and he kept his head.

"I might have known," he said under his breath. Then he paused a while. "But it was clever," he added, "infernally clever. Paul Carney is a good actor. I'll say that for him."

He stood clinging to the ladder with his sound arm, and listening intently. But not the slightest sound penetrated the recesses of this deep vault.

The pain in his bruised shoulder was dying away a little, but the whole arm was still numb. Phil went cautiously back to the foot of the ladder. Then he felt for his match-box.

Thank goodness, it was nearly full. He struck a match and held it up. Its small flame was not sufficient to show him the walls of his prison. What it did show was the stump of candle which Paul Carney had dropped.

"That's a bit of luck!" said Phil gratefully, as he picked it up and lit it, "Now for a search."

Holding the candle well up, he started towards the nearest wall. The air was musty, but quite breathable. The floor, he noticed, was covered with a thin film of what seemed to be dried mud. The wall, too, when he reached it, had a similar coating.

Phil touched it with his finger, and it crumbled away in flakes.

"There's been water here," he said. "That's odd! It looks as if the river did reach it at high Nile. Yet I'd have thought the hotel was a long way above the reach of even the biggest flood."

He went on and made a circle of the place. It, was not so large as he had thought, not nearly so big as the cellar overhead. Walls and floor alike were of solid stone, covered with a sort of cement. One thing was very sure. There was no door or passage leading out of it. The same blank wall surrounded him on all four sides.

Apparently the only way out was the trap overhead, yet Phil was certain there must be some other opening, for it was quite clear that fresh air got in somewhere. The trouble was that he could not find the opening. No doubt it was somewhere close under the roof, and that was a good ten feet overhead.

He thought of the ladder, and went back to it. But the ladder was a hugely, massive affair. Two men could hardly have moved it. For himself, especially with his damaged arm, any attempt of the sort was simply foolishness.

The candle was burning down. He felt he must not waste it. He blew it out, and sat down on the floor in the utter darkness. Then, by way of doing something, he took off his shirt, and set to rubbing his bruised shoulder. It was abominably painful, but he knew that the one cure was to keep the circulation going, and he stuck to it.

Quite suddenly he stopped, and sat up in an attitude of eager attention. A sound had reached his ears, and, slight as it was, it was startlingly loud in the intense silence of the subterranean place.

It was a trickle and splash of water.

Very quickly he got up, and, sacrificing another of his precious matches, relit the candle, and started to investigate.

It did not take long to find out what was up. From somewhere in the roof a stream of water was pouring steadily downwards, splashing on the dry floor and spreading in a widening pool across the muddy cement.

Phil watched it with wide eyes.

"It's a cistern!" he said in a hoarse whisper. "A cistern! And like a fool I never suspected it! It's fed from the rain-water tanks on the roof, and Paul or his father had turned the water on!"

There was dumb despair on his face as he looked upwards to where the single jet sparkled blackly in the candle-light as it spurted remorselessly downwards.

Down it came. The flow was increasing as the long-disused pipe cleared slowly of the dust which choked it. The dark pool spread faster across the floor.

LES O'HARA, coming back into the cellar at sunset, found everything neatly packed, and all the baskets strapped and finished.

"It's a good worker he is," he remarked, with a satisfied air. "And a nice fellow, too. The thrip will be a dale nicer, wid a chap like that along wid us."

A gong, thumped above, sent faint echoes clanging down into the vault.

"Supper, bedad, and it's meself that's ready for it," he remarked, and went back up the stairs.

He was surprised to see no sign of Phil at the supper table, and, finishing his meal quickly, went up to the room which had been assigned to Phil and was next to his own.

Phil was not there. Instead of rushing off to Joe Fosdyke, and telling him that Fernie was missing, Les set himself to a quiet but thorough search of the whole big building. It was not until he was quite certain that Phil was nowhere about that he allowed his suspicions full play.

In his way Les O'Hara was quite as much a character as Phil himself. He was older than he looked, he had knocked about a lot, and he was very well able to put two and two together.

Knowing what he did know, and remembering the scene of the morning, he at once made up his mind that Phil's disappearance was somehow due to the Carneys.

Les, back in his room, which was on the top floor, sat on the edge of his bed, kicking his short legs, and frowning. For quite five minutes he remained there, then his brow cleared a little, and he got up briskly.

A broad veranda runs along every floor of Paster's Hotel, and French windows open on to it from each room. Les went out on to the veranda and looked down.

There was no moon, and though the stars burnt like lamps in the clear vault above, the night was dark.

Les craned over the railing till it almost looked as though he were going to take a header into the depths beneath.

"'Tis aisy," he said, in a satisfied tone—"dead aisy!"

Going back into his room he slipped off his boots and put on a pair of sand-shoes. Then he took a coil of rope from a drawer and went out again.

The one end of the rope he fastened firmly to the veranda rail, the other he dropped softly over. He took hold of the rope, swung his leg over the rail, and began to climb downwards.

Les had the wiry strength of a monkey, and was as good for heights as any mountaineer. In a very short space of time he was safe on the veranda, immediately beneath the one from which he had started. Here he paused, listened a moment, then, in his rubber-soled shoes, went creeping onwards quietly as a cat.

He passed half a dozen windows, all dark and quiet, and at last reached one which was covered by a drawn venetian blind. Through the slats leaked the rays of an electric light, making bars of light and shade on the boarded floor of the veranda.

Here he paused, and, crouching down, came close to the blind, and lay almost flat on the floor, listening intently.

For some time there was no sound whatever, and the slats of the blind were so tilted that it was impossible for him to see into the room.

Les waited patiently, and at last his patience was rewarded. He heard the door of the room open, and someone came in.

A chair creaked.

"That you, Paul?" came the harsh voice of Luke Carney.

"You've got a nerve, father!" replied Paul Carney, "I'm hanged if I could sleep."

Paul's voice was hoarse. Les stiffened. He felt his nervousness behind it.

"Nerve?" repeated the elder Carney. "What's there to worry about, you fool?"

"Nothing—nothing, I suppose. Yes, it's all right. No one suspects anything."

"They don't seem to have missed the brat yet," said Luke.

"They're too busy. But they will in the morning. There'll be trouble then."

"Trouble—bah! What's it matter to us? The brat's fed up with work. He's gone back to his slum. That's what Joe is to hear."

Les hardly breathed. His whole body was stiff with the strain of listening. So he was right, after all. It was the Carneys who had got rid of Phil. But how? Would they betray the secret?

"Fosdyke won't believe that," said Paul, "There'll be a search. You can bet on that."

"Let them search!" snarled his father. "Let 'em search till they're black in the face. I don't suppose there's a soul in the place who knows of that hiding-place."

"The manager might, or some of the servants."

"You make me tired! I know for a fact it hasn't been used for years. The only reason I knew of it as that when I stayed here, six years ago, they were doing repairs to the roof, and I saw the tanks."

Paul cut in:

"Did you turn on the water?"

"Of course I did!" Luke Carney laughed hideously. "I'll lay the brat's enjoying himself. Teach him to poke his nose into our concerns."

"Or to make a fool of me before the whole crowd!" added Paul as viciously. "But see here, father," he went on, "are you sure old Fosdyke is going to this place you talked of?"

"T'zin? Yes, he says so. He wants the local colour. You know he cribbed the story from Fernie's first book."

"Professor Fernie's, you mean?"

"Of course! The cub's father."

"What happened to him? Is he alive?"

"Not likely. The Touaregs, the masked horsemen, collared the lot. There wasn't one left of the whole expedition, so far as I know."

"Then who's to show us where the stuff is hid?"

"That's the rub," replied the elder Carney. "I can't tell for certain, though I have a suspicion. It's in the vases, anyhow."

"How are we to get it?" demanded Paul bluntly.

"Wait and see! This is our chance to get to T'zin. Once we're there we can spend our time in the search."

Lee waited no longer. True, this talk of treasure was interesting enough, but it had nothing to do with Phil. So far as Phil was concerned, he had learned all he was likely to learn. As he crept silently away he was putting his information together in his quick, active brain.

These two ruffians had put Phil away. It was in some place connected with the hotel, yet one the existence of which no one about the hotel was likely to be aware. The one clue he had to it was that it was some receptacle into which water could be turned.

A tank.

Les was a boy who used his eyes. Short as had been his stay in Egypt, he knew that many of the larger houses in Cairo have rain-water tanks in the roof.

Without delay he made his way down into the kitchen regions. Though it was getting late, there were people still about, and presently he found the man of whom he was in search. This was Abdullah, the swarthy hall-porter, who, having finished his supper, was seated, cross-legged, on a wooden bench in the courtyard, smoking a long-stemmed chibouque.

Abdullah, Les knew, had been at Paster's for years, and was more likely to know the secrets of the old building than anyone else. But Les also knew that the last thing any Easterner will do is to give a straight reply to a quick question.

He sat down beside the man and waited for a few moments.

"Does it ever rain in these parts, Abdullah?" he asked presently.

Abdullah, who spoke quite good English, admitted that it did sometimes, and by degrees Les got the conversation round to tanks, and heard that there was a big rainwater tank on the roof of the hotel; but since water had been laid on by the English from an artesian well it had never been used. The porter, however, allowed that it was probably full, and could be used in case of fire.

Les suggested that he would like to see it, and Abdullah was persuaded, by the offer of some small coins, to climb to the roof and show the tank.

It was a big concrete cistern and very much like any other of its kind, and Les, after opening the trap, soon discovered that there was certainly no one in it. Besides, he remembered what Carney had said about turning on the tap, and, again putting two and two together some suspicion of the real truth began to dawn upon him.

"Where does the water run away when the tank is full?" he inquired.

"There is a great cistern below," answered Abdullah. "It is to that the pipes descend."

"Where is that cistern?" inquired Les; and it was with an effort he kept his voice level.

"It is beneath the cellars," Abdullah told him. "In the morning I will show you."

"But we are off first thing in the morning," objected Les. "Show me now, Abdullah, and I will give you five more piastres."

Abdullah shrugged his shoulders.

"Truly the ways of the English are strange," he said. "Thou should be in thy bed, and so should I."

He sighed.

"Still, I will go," he added.

Les' heart-beats quickened as Abdullah led him into the wine-cellar and switched on the light.

"It is beneath our feet," he said.

"How do you get down to it?" demanded Les.

"I know not. There is doubtless a trap leading into it. But not within memory hath it been used, and I know not even where the flag lieth!"

Les paused a moment. His first impulse was to urge the man to help him to hunt, his second to let him go. If the trap had been recently used he could find it himself. In any case, he could get help from Joe or Reggie, if the need arose, and this was a matter much better kept from the wagging tongues of natives.

He yawned quite naturally.

"Well, I'm much obliged to you, Abdullah!" he said. "It's all very interesting. But, as you said just now, it's time for us to be in bed."

He turned away, and Abdullah, only too glad that the "Ingreezi" was satisfied, flopped away in his loose slippers.

Les followed him upstairs, bade him good-night, then, watching him out of sight, secured a candle, and hurried back into the cellar.

The floor of the cellar was covered with a thin film of dust, and at once Les' quick eyes noticed two pairs of footsteps running across into the inner part of the vault. Then he began to search for the flag.

With his usual cunning, Paul had worked dust well into the cracks after closing down the trap, and it was some time before Les discovered it. But once he had found it, all his suspicions crystallised. Here was Phil's prison; not a doubt of it!

He stooped, got hold of the ring, and began to pull. But the weight of the stone was too great for him. He could not move it.

He paused. It was quite clear that he must fetch someone to help. The question was, who should it be? First he thought, of Joe. But Joe Fosdyke, good fellow as he was, had a quick temper. He might flare up, make an awful row, call in the police, and have the Carneys arrested at once.

Les was not the least averse to having the Carneys arrested but what stuck in his mind was this matter of the treasure at T'zin, of which the Carneys had spoken. They seemed to have some notion of where it was, and Les had already made up his mind that Phil and he were going to have a share of it.

He was off like a flash, and went racing upstairs. Luckily he knew Reggie's room. He knocked, heard a lazy voice say, "Come in!" and found Reggie, in a suit of blue silk pyjamas, lounging in a long chair, with a cigarette in his mouth and a novel in his hands.

His sleepy eyes widened at sight of Les.

"You're a bit late in the day, laddie—or is it early?" he drawled. "Don't tell me that Joe means to start at midnight!"

"It's not Joe that wants ye, Mr. Dacre. It's mesilf. Phil Fernie's in the cistern below, and I want ye to help me get him out."

"In the cistern!" repeated Reggie. "But, my dear old top, what a place to choose for his ablutions! And what an hour!"

"'Tis, no choice of his," said Les rapidly. "And it's drowned he'll be if we don't hurry!"

Reggie roused, and got up quickly.

"Lead on, my son! Let us to the rescue! But ought we not first to call the good Brander? it appears to me that we are wasting a valuable opportunity for a scene. 'Snatched from the Cistern!' How does that strike you for a headline?"

"'Tis no joke!" said Les earnestly. "Come along wid ye, Mr. Dacre!"

Les' manner sobered Reggie, and he followed him quickly through the long corridors and down the stairs. There was not a soul about, and they reached the cellar unseen.

Les led the way straight to the trap of the cistern.

"You don't mean to say he's down there?" demanded Reggie. "How in sense did he get into such a place?"

"Sure, he'll tell you himself! Take a hand now wid that stone!"

Reggie stooped, and got hold of the iron ring. For all his effeminate appearance, there was plenty of strength in those white hands of his, and with a crunch and a creak up came the flag.

"Are you there, Phil?" asked Les.

But almost before the words were out of his mouth Phil Fernie's head appeared out of the black depths. Les gave him a hand, and he scrambled rapidly up off the ladder. In the light of the candle his face was wan and lined. Those terrible hours had left a mark upon him, which would not easily disappear.

"How did you find me, Les?" was his first question.

"I'll be telling ye when we get upstairs," replied Les. "Sure, this is no place to be talking!"

"A most sensible remark, O'Hara," said Reggie. "This abominable vault gives me chills all down the spine!"

Back in Reggie's room Reggie put Phil in his long chair, and, going to a cupboard, mixed a dose of brandy-and-water.

"A nip of this will do you a power of good, young fellow!" he said, in his quiet drawl. "Not a word, but just put it away. Then you can spin us the yarn."

Phil choked a bit over the unaccustomed spirit, but it was really just what he needed. Then quite quietly he told them what had happened.

"My only aunt!" remarked Reggie. "I never liked Carney, but this beats the band! I never realised that we had a real heavy villain in the cast."

"And how did you find him, O'Hara?" he asked.

Les told him of his descent over the balustrade.

"Joe will break his heart when he hears," said Reggie. "This beats the 'Witch of the Desert' to a frazzle!"

"Wait now," said Les, "there's more to it yet!"

He went on to describe what the Carneys had said about the treasure.

"'Tis at this place, T'zin, where—"

"T'zin!" broke in Phil sharply. "You don't mean we are going there?"

"Sure we are," answered Les. "Didn't ye know it?"

"Never dreamed of it," cried Phil. "That's the place where my father disappeared. He was looking for this treasure. It's supposed to be under what they call the Lost Pyramid."

"D'ye know where that is?" demanded Les eagerly.

"No. I was there once with my father, but T'zin is a big oasis out in the desert, and the old pyramid, he said, was most likely hidden by drifting sand. We hadn't the stores to make any long stay, so he came back to Cairo, refilled, and that time went without me. Then I heard Touaregos had raided the expedition and killed him."

"It all fits in," said Reggie quietly. "My young friends, I have a notion that it's up to us to see that the gentle Carneys do not handle this ancient oof. It occurs to me that we could make better use of it ourselves?"

"Isn't it what I've been saying to mesilf iver since I heard?" exclaimed Les. "Sure, that's why I came to yourself, Mister Dacre, instead of going to the boss."

"A wise precaution," drawled Reggie. "I take it, then, that your idea is to allow these two gentlemen to remain under the impression that our friend Fernie is down and out? Am I correct?"

"Sure, you're correct," answered Les. "If we lave them to be thinking that, they'd be off their guard. Sure, we'll let them do the work, and we'll scoop the goods."

"An excellent division of labour," agreed Reggie, "and one which I only wish hold good in all departments of life."

"But I don't understand," broke in Phil, frowning. "How can we manage without their knowing—the Carneys, I mean? They're bound to see me to-morrow."

"But we have already agreed that they must not see you," replied Reggie.

"Must I give up my job and stay in Cairo?" asked Phil in dismay.

"Not at all," said Reggie quietly. "You do not understand the arrangements, my son. The party travels in two divisions. One, including all of the actors who will be engaged in making the film, go down the river in a dahabeah. Joe has hired one of Cook's boats for the trip. The rest, including the camels and donkeys, are going by train as far as Feronan, and from that point will travel by the caravan route to the oasis. The Carneys, though nominally in charge of the animals, have insisted on going by boat, and rather than have a fuss, Joe has allowed their claim. You, Fernie, will be handling the white dromedary, and will therefore go by train. Now do you understand?"

Phil drew a long sigh of relief.

"Splendid!" he said! "Now it's all as plain as paint. Which party starts first?"

"The boat party leave first. The train does not start till about ten."

He went to a drawer, took out some money, and handed Phil a couple of notes.

"Take this," he said. "You can repay me when you like. You must leave the hotel, spend the rest of the night in Cairo, and be at the station in good time in the morning. Les, here, will tell our good friend Joe that you have gone on to look after your charge."

Phil jumped up quickly.

"That's all settled, then," he said. "I'll do exactly what you say, Mr. Dacre, and I'm tremendously obliged to you!"

Reggie laughed.

"The boot's on the other leg," he said. "I'm in with you two for a share in the treasure of the lost Pyramid, and don't you forget it. Now, good-night, and good luck!"

Five minutes later Phil was slipping quietly away down a dark street of the town. He was making for his old quarters at the house of Achmed, the saddler.

Achmed and his household were asleep, but Phil had no difficulty in reaching the little room where his rug was spread. In spite of what he had gone through—perhaps because of it—he was asleep in five minutes, nor did he wake until the sun, shining through the narrow window, roused him.

He got up, washed, went down and found the old saddler drinking his morning coffee. Phil did not explain what had happened; merely said that he had wished to sleep for his last night under the old roof. He shared Achmed's breakfast, said a last good-bye, and was off.

He was at the station an hour before the train was due to leave, but knowing the officials and language as he did, had no trouble in finding the vans set apart for the Golden Apple Company. The animals, he found, were in the charge of an Egyptian named Selim, and he walked up the platform looking for this man.

Suddenly he stopped short; then, quick as a flash, dodged into the shelter of an open doorway and stood tense and watchful.

Two people were walking down the platform just ahead. They were a white man and a white boy, and it did not need more than one glance to assure Phil that they were none other than Luke Carney and his hopeful son.

Phil's brain was in a whirl. What was he to do? It was quite clear that at the last minute arrangements had been altered, and that, after all, they were going to travel by train and not by boat.

PHIL fully realised how short his shrift would be if he fell into the hands of the precious pair, and it must be confessed that his first idea was simply to bolt and clear out altogether.

Second thoughts were wiser. The boat had left at least an hour earlier, and if he bolted he would not only lose his job, but also his friends, and his chance of a share in the Pyramid treasure.

He drew back farther into the shadow, while his brain worked nineteen to the dozen, trying to devise some way of getting out of the difficulty.

His first idea was to wait in hiding until the train left, then go on by a later one. But the money which Reggie Dacre had lent him was not enough to take him so far as Kerouan, so that was out of the question.

A native boy, about his own age, came loitering up the platform past Phil's hiding-place, and in a flash a new and daring idea darted through his brain. He himself was more accustomed to native than to English dress, and he talked Egyptian as well as any native.

He felt certain that he could disguise himself well enough to take in any white man, even Carney.

The question was whether he would have time to do it before the train started. At any rate, he would try.

Waiting only until the Carneys were out of sight, he hurried swiftly back down the platform. Having been in Cairo so long, he knew heaps of people, and among them two of the porters at the station.

Luck was with him. Darting into the porters' room, there was one of these men, Ismail by name, seated on the floor smoking.

He greeted Phil in the grave way common in the East, but for once Phil threw aside all his manners, and fairly dashed at the astonished man.

"How long will it be before that freight-train starts, Ismail?" he demanded.

Ismail looked rather startled, and said it was due out in half an hour.

"Half an hour! Then there's no time!" exclaimed Phil, in such despair that Ismail's heart was touched, and he inquired what troubled the heart of his "Ingreezi" friend.

"I've got to go by that train," Phil told him. "But not in these clothes. I must be in native dress, you understand. The white men must not know that I, too, am white."

Ismail's dark eyes tightened. Anything in the way of a plot appeals tremendously to the native. The porter scented some deep conspiracy.

"As a spy?" he demanded eagerly.

"It is so," agreed Phil.

"Then, by Allah, it shall be done!" declared Ismail scrambling to his feet. "Wait for me here, Ernie Effendi; I will return soon."

A quarter of an hour passed. It seemed like four hours. Then, to Phil's intense relief, there came Ismail with a bundle over his arm. It was a complete suit of native dress, fez and all. More than that, he had secured from somewhere a bottle of hair-dye of a dark-brown colour.

"You're a brick, Ismail!" cried Phil, in delight. Then, seeing the man's puzzled face, he thanked him heartily in his own language, and at the same time began to strip with amazing speed.

Ismail helped, and, in spite of his anxiety, Phil chuckled inwardly to see how keen the man was.

It was about the quickest change on record—change not only of clothes, mind you, but complexion as well. It was an English boy in English clothes who had entered the porters' room: it was a brown skinned, bare-legged Egyptian who came out, and Phil flattered himself that it would take sharper eyes than Carney's to penetrate his disguise.

Leaving his English clothes with Ismail, Phil bolted down the platform, arriving at the siding just as the bell began to ring for the train to start.

He spotted Selim at once, and went straight up to him.

"Fosdyke Effendi has sent me to help thee with the beasts," he told the man in fluent Egyptian.

Selim, a tall, fine-looking man looked at him doubtfully.

"It is true," he said, "that I was told that another was to be here to help upon the journey, but, he was a white lad."

"That is the truth, Selim," agreed Phil. "His name was Fernie, and he it was who lived at the house of Achmed the saddler. He hath, however been sent by the dahabeah, and the order is that I take his place."

An inspector came striding up—an Englishman.

"Hurry up!" he said curtly. "Quite time this train was off!"

Selim realised there was no time to make inquiries. He was short-handed, and only too glad of extra help.

"Enter then," he said to Phil; "but if thy words are lies, on thy own head be it!"

Next moment Phil found himself in a box-car, in company with Selim and two Egyptian drivers and almost at once, the train moved slowly out of the station.

It gathered speed, and soon was rattling and clanking through the suburbs. Houses faded, and were replaced by fields of cane and cotton.

Phil heaved a sigh of deepest relief. He had accomplished his object, and was safely started on the first step of his adventurous journey.

It was an hour before sunset on the second day after leaving Cairo that the trucks with the animals were shunted at the siding at Kerouan.

The place was on the bank of the Nile, the broad waters of which glowed red in the light of the low sun.

The station stood upon the east bank, and a barge was waiting to ferry the contents of the trucks across the river. On the west side was a small native village, surrounded by fields of millet and cane and a few palm-trees. Beyond the enormous desert stretched golden to the sky line.

Phil stood staring out across the vast, bare expanse, noting the caravan-truck which wound away over the sand-hills. His heart beat hard as he thought of what might lie beyond that far horizon.

"Get to it, you lazy scum!"

It was the harsh voice of Luke Carney that roused him from his musing. A whip-lash whistled and cut him sorely across the shoulders.

For the moment he forgot his assumed character, and spun round angrily. He saw the look of surprise on Carney's face, and instantly turned humble again.

"I go, Effendi!" he said quickly in Egyptian, and hurried away to help Selim. But he was conscious that Carney was staring after him, and inwardly he cursed his carelessness, which had come so near betraying him.

It was a job to get the animals on to the barge. The camels were particularly troublesome, and when the job at last was done the barge was very low in the water and almost dangerously crowded.

Selim gave the word to cast off, the native boatmen swung their wide-bladed oars, and the clumsy craft moved slowly across the stream. The Carneys meantime got into a small boat, and were rowed quickly across.

Phil, keeping carefully out of their sight, was relieved when the barge came safely under the far bank. But this bank, he saw, was high and steep, and the landing was not going to be easy.

The mules were got ashore without much trouble. Mules climb like cats, and these made no trouble about going up the bank.

It was different with the camels. Still, by dint of patience, three were got up all right, including the big white dromedary. The fourth refused to budge.

Selim, who had kept his temper very well up to now, at last grew angry.

"Son of Eblis!" he roared, and struck the brute fiercely.

The sulky brute still refusing to move, Selim got hold of its head-rope, and tried to drag it along. Stupidly, he had taken a turn of the rope around his wrist.

Suddenly the camel whirled round. The action was so unexpected that Selim was swung clean off his feet. Phil heard a yell of terror, and saw the unfortunate man flying through the air. Next moment he had let go of the rope and gone smack into the river.

Phil picked up a rope, and sprang to the side of the barge. The Egyptian had gone under, and for the moment was out of sight beneath the dark, muddy water. When he rose again he was yards out. The current had hold of him, and he was being swept rapidly downstream.

"Catch!" shouted Phil, and flung the rope.

Selim made a feeble grasp at it, and missed it.

"Help!" he cried hoarsely. "Help! I drown!"

He could not swim a stroke, and next moment was under again. Phil saw that something had got to be done, and quickly, too, if the unlucky man's life were to be saved. He did not hesitate, but jumped straight in.

Phil swam well, and, with the current helping him, reached Selim before he had gone down again. The man was mad with terror, and it was all Phil could do to avoid his clutching hands.

"Keep still!" he snapped. "Keep still, or I leave you!"

Seizing his chance, he got behind the man, and, catching him by the back of his coarse skirt, set to pushing him in towards the bank.

The current was far too strong to fight, and Phil saw that the only chance was to work with it. The two were carried down for a hundred yards or more before a lucky eddy swung them in towards the bank.

The other Egyptians were making no effort to help. As Phil well knew, they were one and all convinced that the man who saves another from drowning is himself doomed to die within a year.

By this time the Carneys had realised what was happening, and just as Phil felt ground under his feet he saw Paul Carney scrambling down the bank with a rope over his arm.

"Here, catch this!" he shouted harshly, as he flung the coil to Phil.

Phil himself was all right, but he was badly blown, and just as pleased to have help in getting Selim up the bank.

Getting firmly on his feet he made the rope fast around Selim's body, and motioned to Paul to haul away.

A minute later Phil and the Egyptian were both safe again on dry land.

Paul was annoyed.

"What the blazes are you two fools playing at?" he demanded angrily. "Can't you land a beggarly camel without—"

He stopped short, and Phil recognised that the fellow's dull blue eyes were fixed upon him with a strange look of suspicion.

Was it suspicion? It seemed to be almost more like fright.

"What's the matter with your face?" cried Paul in a queer, cracked voice. "Who are you?"

Instinctively Phil put up his hand to his face, and as he lifted it he saw that the brown dye was half washed off, and that the white, skin showed in patches. In a flash he realised that his face, too, must be in the same condition.

Paul's face was convulsed.

"It's—it's—" Then, with an oath, "You're Fernie!" he roared.

Phil saw it was all up. He dashed at Paul caught him round the waist, tripped him, and flung him heavily. Then he bolted for dear life.

IT was madness. In his heart Phil knew it. There was nowhere to run to, no place of refuge. Joe Fosdyke and the rest of the company were not due for two days yet. Besides himself, the Carneys were the only whites within miles.

He ducked down under the rim of the high bank. It was low Nile, and the shrunken river ran twenty feet beneath the level of the surrounding country.

It was in his mind to reach the boat which had brought the Carneys across, to get into it, and pull straight down the stream. Once round the big bend below, it seemed possible that he might find some hiding-place where he could lie up and wait till night.

Before he had gone fifty steps he heard Paul shouting furiously to his father.

"He's under the bank!" roared Paul. "It's Fernie! Stop him, father!"

Phil redoubled his pace. His heart was in his throat; his mouth was dry; he felt like one running in a nightmare.

There was the boat only just ahead. It lay on the near side of the barge where the one last camel still stood defying the other drivers. Hope rose within him, and he was beginning to believe that he might actually do it, when down the bank came plunging Luke Carney.

The tamer's face was livid with rage. His eyes held a dull glow ugly to see. His big hands were knotted.

Phil stopped. He tried to dodge, but he was completely blown. In an instant Carney was on him, and his iron fingers closed on Phil's throat. In savage silence the man gripped him, lifted him, and flung him, bruised and breathless, to the ground.

At that moment Paul came panting up.

"The young brute! Let me get at him!" he growled viciously.

"Stand back!" said Luke harshly. "You fool! Haven't you made fuss enough already? These niggers have tongues, and, remember, he's pulled one of them out of the water."

Paul looked a trifle abashed.

"What do you mean to do, then?" he asked sulkily. "You're not going to turn him loose, are you?"

Luke turned upon his hopeful son, with an unpleasant glare in his eyes.

"Can't you keep your infernal mouth shut?

"Go and find out from one of the men where our quarters are for the night," he continued.

Paul slunk off.

"Get, up, Fernie," said Luke, in a somewhat milder tone. "Don't try to bolt again. In any case, it will be of no use. There is no cover for miles; and, I give you my word, I'll hunt you down wherever you go!"

Phil had risen to his feet. He shrugged his shoulders.

"You mean you want to murder me on the quiet!" he said scornfully.

Luke ground his teeth, but still kept a hold on himself.

"Do you think that the life of a brat like you is going to stand in my way?" he sneered.

"All the same," he continued, "I'm inclined to give you a chance. I believe you can be useful to me. Anyhow, you'd best understand right now that this will be your only chance. If you play the fool I'll shoot you right off, and chuck your body into the river! Then I sha'n't wait for Fosdyke, but go on to T'zin at once."

Paul came back.

"There's a hut for us just outside the village," he said sulkily.

"Then you'll come there with us, Fernie," said Luke. "And if you know what's good for you, you'll make no bones about it."

Phil glanced at the man's face. It was hard as a stone, pitiless as a tiger's. He made the best of a bad job.

"All right," he said quietly. "I'll come."

The house reserved for the Carneys was the best in the village, but that was not saying much.

As soon as they were inside, Luke Carney shut the door, and, opening out a camp-chair, sat down. Paul did the same. Evidently Phil was to stand, but having no intention of doing any thing of the sort, he picked up a packing-case and sat upon it.

"Get up!" snarled Paul. "Get up, you scum!"

Phil looked at him.

"Dry up!" he said curly. "Just remember you're not my judge, and that I've licked you twice, and can do it again if need be!"

Paul leaped to his feet, foaming with rage. But his father caught him by the arm.

"Sit down, you fool!" he said, with a harsh laugh. "Let the bantam crow. He won't have too long to do it."

"I'll take precious good care he doesn't get off the hook a second time!" snarled Paul, livid with rage.

"Keep your mouth shut!" ordered his father roughly, and turned to Phil.

"See here, Fernie, in spite of what Paul says, I'm inclined to give you a chance. Are you game to take it?"

"Game? I don't know what you mean!" retorted Phil. "I don't particularly want to die, and I certainly don't want to be smothered. But since I've got nothing to buy my life with, I don't seem to stand much of a chance."

Luke bent his hard eyes on the boy.

"Don t you be too sure of that. I guess you're the son of Professor Fernie?"

"I am," Phil answered.

"Him as was down in T'zin, looking for that there lost pyramid?"

"That's him."

"You were with him, weren't you?"

Phil nodded.

"How much do you know about it?" demanded Luke bluntly.

It was on the tip of Phil's tongue to say "Nothing at all." But he checked himself. In the first place, it was not quite true; in the second, it struck him the silence was the best policy. So long as the Carneys fancied that he had any information to impart, so long would they keep him alive. From what Les O'Hara had said, he was aware that the Carneys had only the sketchiest information either as to the treasure or its location.

Luke saw his hesitation, but put it down to the wrong cause.

"See here," he said, and there was a touch of eagerness in his hard voice. "You tell me where this here pyramid is, and give me your word you won't say nothing about that little matter up to Cairo, and you can go about your business, safe and free.

"You must take me for several more sorts of a fool than I really am!" he answered scornfully. "Suppose I did tell you, what earthly guarantee have I got that you'll keep your word?"

"As much as I have that you're a-telling the truth retorted Carney angrily.

"There you are again. If I do tell you what I know, you might say it was all lies, and make that your excuse for knocking me on the head."

Luke Carney bit his thin lip. He was beginning to realise that this youngster was a sight smarter than he had imagined. At the same time, Phil had conveyed to him the impression that he knew more than he really did.

"If you don't tell me, I'll darned well make you!" he threatened.

"Don't be a fool," retorted Phil. "I know you're quite capable of torturing me, but even if you did wring something out of me, it wouldn't be the truth. There's only one way of doing it. You've got to take me to T'zin, and go shares."

Paul Carney sprang up in a rage.

"Don't listen to him, father! You leave him to me! I'll make him talk!"

Luke turned furiously to his son. His language was lurid. Paul, livid and actually trembling, shrank back, and Luke addressed himself again to Phil.

"Do you or don't you know where the stuff is hid?" he demanded.

Phil's face hardened.

"Do believe me when I say I'm not quite a fool. If I can't keep my life I can keep my counsel. I'm not going to say a word about it until I know that I'm safe, and that I get my proper share. Seeing that it was my father who was the first white man to get on the track of it, it ought to be all mine. But since, as he told me, it's worth more than a million, I can do with a part of it."

Phil saw the covetous glare in Luke Carney's eyes. He felt that he had gained his point, and with it a respite for the present, at least.

All the same, he was hardly prepared for the storm which burst, or the awful threats which Luke poured out. But he sat through it, unmoved, and at last, just as he had expected, the man gave in. Or, if he did not quite give in, at any rate, he compromised.

It was arranged that they should start first thing in the morning, Phil with them—that he should show them the pyramid, and take a third share of what was found.

"And if you don't find it for us," Luke ended. "Heaven have mercy on your soul, for you can bet I won't!"

With which grim threat Phil was bundled into the back room, given a mouthful of food and a drink of water, then tied neck and crop, and left in his wet clothes to spend the night as he best might.

"You ain't a-going to play no more tricks on us, you can take your oath to that!" was Paul Carney's last threat, as he closed the door and rammed the bolt home.

Relieved as he was to have escaped instant murder, it would not be fair to say Phil was happy. In addition to extreme bodily discomfort, he was only too well aware of the fact that he did not know where the lost pyramid was to be found. It is true he had some idea of the direction in which it lay, but that was about all.

In any case, he had not the faintest idea of letting these precious Carneys share even what little knowledge he had. He had been playing for time, and now that he had gained a little time, he had every intention of making good use of it. In other words, his one idea was to escape.

He could not hide from himself, however, that his chances looked anything but rosy. The room he was imprisoned in was small, bare, and, barring the moonlight, which shone in through the narrow, unglazed window, quite dark.

The doors were both locked and the window barred. Also, the partition wall was so thin that any sound would be easily heard by the Carneys in the larger room.

For all that, Phil did not give up hope. He believed that, if only his hands were free, he could find some way out.

There was the rub. Clearly the Carneys had had the same idea, for they had tied his wrists so firmly that there was no human possibility of wriggling free. Also, they have taken away his knife.

But even they had not quite realised the strength, activity, and, above all, will-power of their prisoner.

Phil waited patiently until he had heard his gaolers go to bed. Not till they were both snoring did he begin his operations.

By this time the moon was well up, and shining strongly through the barred windows, showed a pile of rubbish lying against one wall of the filthy little place.

Unable to rise to his feet, Phil rolled over to this and with numbed fingers began fumbling in it. It seemed to be nothing but old com husks, tobacco-leaves, and similar refuse, and his heart sank as he realised how useless this was.

But he stuck to it, and a thrill shot through him as at last his groping fingers touched something cold and hard.

With great difficulty he got it out, and found, to his delight, that it was an old husking-knife. It was broken, rusty, and the blade was gapped, but Phil was more pleased than if he had found a diamond.

The next thing was to wedge it, so that he could use it. This took a good half-hour, and, in spite of the cold of the desert night, he was sweating before he had accomplished this task.

Then at last he was able to begin sawing at the cords binding his wrists. They were of coir rope, new and hard, and for a long time it seemed as if he could make no impression upon them.

But gradually a little pile of fluff appeared, and hope, almost dead, began to dawn again within him.

By this time he was suffering from the most atrocious cramp, both in his arms and legs. The pain was so keen that he could have screamed.

The perspiration steaming into his eyes nearly blinded him, and his heart thumped like a hammer.

Still he went on, and after another hour there was a slight snap, and suddenly the cord dropped away. In a moment his wrists were free; in another his numbed fingers were wrestling with the rope around his ankles.

He got it off, only to find that he was too stiff to rise. He had to waste five more precious minutes in rubbing his legs to get back the circulation.

Now to get out. The moon shone coldly on the desert. In the distance he saw the tethered camels standing under the date-palms.

He went to the door and tried it. That was no good. He stepped to the window, and tested the bars. Of these there were two. The first seemed firm, but the other was loose in its socket.

He put his weight on it. Gently at first, then more strongly. It gave a little, then no more.

He tugged. Just when he least expected it, the bar gave. It came clean away, and so suddenly that he stumbled back, and fell heavily on the hard clay floor.

"What's that?"

It was Paul's sharp voice, sharp with suspicion. Phil heard him leap off his bed. Another moment and he would be in the room.

Phil did not hesitate. Springing to his feet, he flung himself into the narrow gap. He got his head through, and where he got his head through he knew that he could get his body.

But the space was so narrow he could not go fast. Before he was clear the inner door burst open.

"Your pistol—give me your pistol, father!" shouted Paul! "The beggar's got free. He's getting through the window!"

HOW he did it Phil never knew, but somehow he must have forced his way between the bars, for the next thing he realised was that he was sprawling on all-fours on the sand outside the window.

He struck the ground like a ball, and like a ball bounced again to his feet.

Instead of bolting straight towards the palms, he swerved to the right, and dashed along under the back wall of the house.

This saved his life, for the next instant a pistol was thrust between the bars, and two shots rang through the quiet night.

Both missed him, and he kept going at full speed. The house was surrounded by a low fence. He took this at a bound, and went racing across the sand towards the palms. His one chance was to reach a camel before be was caught.

Behind him he heard Paul Carney shouting furious threats. He did not hear Luke's voice, and knew from that that the man was not, like his son, wasting time. Luke was a brute, but a brute who had his wits about him.

As he had expected, the front door flew open with a crash, and glancing back over his shoulder, he saw Luke racing across the enclosure, and in his hand was something that gleamed in the moonlight. A pistol!

Luke did not utter a sound, but there was a deadly, purposeful earnestness about his rush which augured ill for Phil if he caught him. And Phil's heart sank, for he knew the man's great strength and activity, to say nothing of his ruthless brutality.

He glanced across at the camels. The nearest was two hundred yards away, and even if he reached it ahead of Luke, he had still to loosen the picket-rope before he could mount. He did not see the faintest hope of doing so, but still he kept on doggedly.

A snapping crack, a thud, a deep oath! Once more Phil looked back. Carney was sprawling on the sand. Clearly he had tried to jump the fence, had caught his foot on the top paling, and taken a heavy fall.

Phil's spirits bounded up again, and he spurted vigorously to take the best advantage of this heaven-sent chance.

Next instant he was under the ink-black shadow of the date-palms, and his fingers busy with the knot of the picket-rope.

Carney was coming again, but not so fast. The fall must have shaken him up, and knocked the wind out of him.

In spite of his desperate need for haste Phil knew too well to try to hurry the camel. From long experience of these queer-tempered brutes he was aware that anything of the kind was fatal.

He spoke quietly to the creature, and to his intense relief it knelt at once. Not till then did he realise another piece of good fortune. The busy Egyptians had left the saddle on its back. The difference this made was enormous, for it is next to impossible to ride a camel bare-backed.

Quick as a flash Phil was on the camel's back, and as he gave the word to start, it rose swaying to its feet.

He glanced back. Luke Carney was about fifty yards away. He was stopped, and, with pistol arm raised, was taking careful aim at the camel.

He was a thought too late. Before he could pull the trigger Phil drove his heels in, and the ungainly beast lurched forward, putting the trunk of the nearest palm between itself and Carney.

This saved Phil, for with the crack and the flash of the pistol came the thud of the heavy bullet, burying itself in the palm-trunk.