RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

"The People of the Chasm," C.A. Pearson Ltd., London, 1923

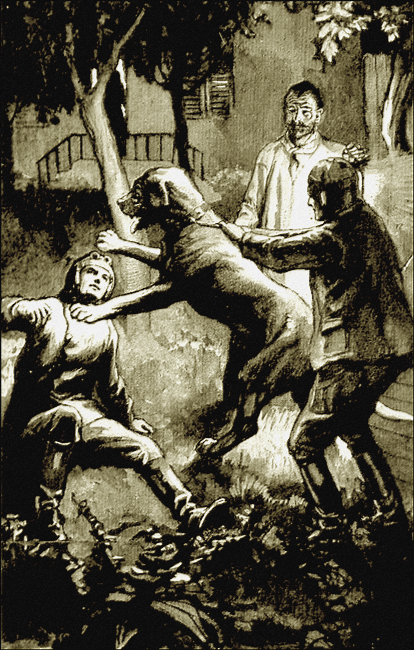

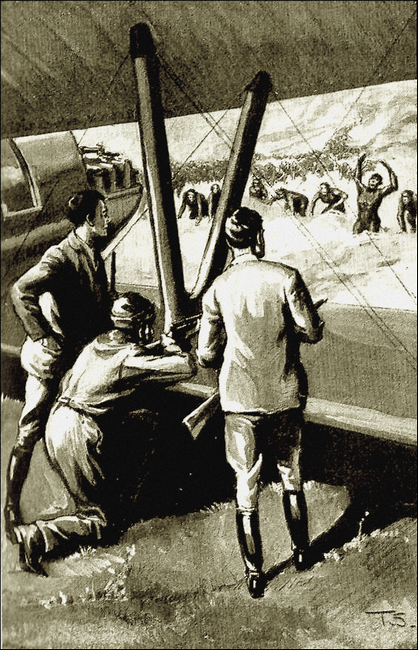

Frontispiece.

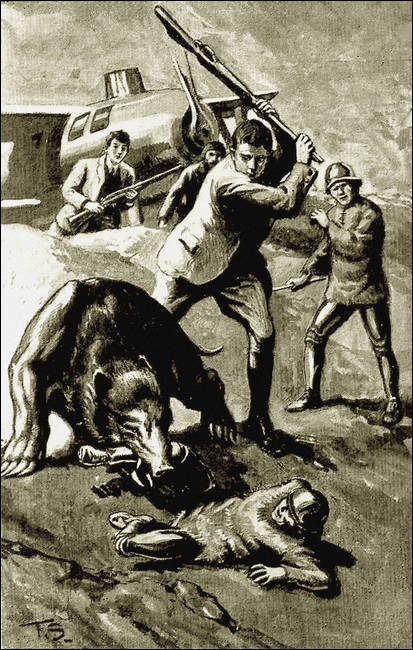

But for Dick, the mastiff's teeth would have met in Monty's throat.

AS the great 'plane roared through the upper air, young Monty Vince sat with his eyes glued to the thick glass window of her enclosed body, and watched the sea of clouds lying like a pearly floor far below. Every nerve in his body tingled with excitement and triumph, for even he, small as was his experience, knew that this first flight of his brother's new machine was a magnificent success.

On and on she flew, and the cloud floor seeming to sink away told Monty that the great machine was still rising. Earth had long since been lost sight of, even the topmost clouds were far below, and they winged their way in solitary splendour, bathed in the cold sunlight of the upper levels.

Presently Monty noticed something new. The deep, steady roar of the enormously powerful engines seemed to be dropping in tone. It was steady as ever, yet certainly not so loud. Yes, there was no doubt about it, and with a sudden feeling of uneasiness, Monty rose from his seat and went forward to where his brother sat in the pilot seat, his long flexible fingers resting lightly on the delicate controls. Beautiful hands Dick Vince had, almost as fine as any woman's, but the left was curiously marred by a long white scar which ran back from the second knuckle, disappearing under the sleeve of his pilot's jacket.

Monty leant over until his lips almost touched the other's ear. "Dick," he said, "Dick, what is the matter? Is anything wrong with the engines?"

Dick Vince looked up with a slight, look of surprise. "Why, Monty—why do you think that?"

"Can't you hear? Don't you notice there's not half so much noise?"

Dick smiled, and the smile lit up very pleasantly his keen, clever face and clear, dark eyes. "Yes, I hear it. But that's only natural, Monty."

"Why?"

"Because of the height, old chap," and as he spoke Dick Vince pointed to the barograph, the height-recording instrument which was fixed on the instrument board in front of him.

Monty looked, and his eyes widened. "Good heavens, Dick, you don't mean to say that we are thirty thousand feet up?" he exclaimed.

"Not quite that, but we soon shall be. Twenty-nine thousand seven hundred is the exact figure."

"B-but isn't that a record?"

"If it isn't it soon will be," replied Dick, with quiet confidence.

For a minute or so Monty said nothing. The marvels of this wonderful aeroplane rendered him speechless. When at last he spoke again his voice had a note of awe in it. "But I thought that no one could breathe at such a height, Dick. There's so little air."

Dick smiled again. "There's none under water, Monty, yet people go down three hundred feet in submarines."

Monty considered a little. "Then this is a sort of submarine of the air."

"Yes. The body is air-tight and almost cold proof. And when we need fresh air I simply turn on a little oxygen."

Again there was silence for a time, and again it was Monty who broke it. "But, Dick, if there is so little air up here how do the wings get a grip? How does the machine manage to fly at all?"

"That is a matter of construction, Monty. For her power, the Falcon is, I believe, the lightest machine ever built. This new alloy of mine saved a deal of weight, and then, these extension wings make a big difference. I get a lot more bearing surface, which makes up for the lesser density of the air."

Monty gazed at his brother with whole-hearted admiration. "Dick, I think you're an absolute marvel," he declared.

Dick turned to his brother. "The Falcon is a success, Monty," he said gravely. "There is no boasting in saying that. But I want you to remember that, but for you, she could never have been built.

"No, don't interrupt me," he went on quickly, as he saw Monty's lips move. "I mean what I say. The credit is due to you just as much as to me. If you had not trusted me, if you had not put up the money, it could never have been done."

Monty shook his head impatiently. "Nonsense, Dick! It's no credit to me. You see I knew you'd make a go of it."

"You could not know that," answered Dick, as gravely as before. "That was impossible. Yet you handed over to me the whole of the legacy that Uncle John left you. As I said before, the Falcon owes her existence as much to you as to me, for if you had not put up the money she would never have been built. People don't trust a youngster like me with money for new inventions."

Monty brushed aside his brother's gratitude with a laugh. "Well, anyhow, she's a howling success, and since you have made me your partner, we're both going to make a fortune. What are you going to do with yours, Dick?"

"Explore," said Dick, quickly. "See parts of the world that no one knows anything about. Fly over the Himalayas and up across the Andes of Bolivia."

Monty's eyes shone. "Me, too!" he cried.

"That's what I'd like best."

A sudden thought struck Monty, and he came back to Dick. "I say, Dick, where are you coming down?"

"How do you mean? I shall return to the aerodrome at Boltham."

"But you can't tell where it is. There is no sign of the earth—nothing but clouds."

"Yes, but when we dip back through the clouds we shall see the earth again."

Monty was silent, but somehow not quite easy in his mind. It was his first big ascent, and the loneliness up here oppressed him. It seemed to him that they were cut off completely from everything human.

And still the Falcon's nose was cocked upwards, and still she rose and rose. The cold outside must have been frightful, for even within the perfectly insulated and electrically heated interior Monty was beginning to shiver. Then quite suddenly the Falcon began to quiver in an odd way.

"What's the matter?" asked Monty, hastily.

"Wind," replied Dick, curtly. "We must have run into something pretty stiff. I've never struck anything like this before, Monty. It's a regular hurricane. I shall have to drop out of it. No machine that ever was built could fight it."

As he spoke he turned the 'plane completely round, and let her nose point downwards. The difference was amazing. All the fearful stress and strain ceased, and the sense of peace was a delightful change.

There was silence for a little while, then Monty spoke again. "Any idea which way we are travelling?" he asked.

"East, I am thankful to say," replied his brother.

"We must be a longish way from Boltham," said Monty.

"We are, I'm afraid, but anyhow, we are not being blown out into the Atlantic."

"But what price the North Sea, Dick?"

"We have petrol enough to cross that at a pinch," Dick told him, "but I hope we shan't have to do anything of the sort. All the same, I wish the clouds would break."

It was now getting late in the day, and although at this height the sun was still visible, yet the big golden globe was not far from setting.

Then, as Monty watched eagerly, suddenly the clouds broke, and they were beneath the thick canopy and flying through the gloom of a late evening. He looked down. "Dick—Dick!" he cried, "we're over the sea!"

"I WAS afraid of it," was Dick's reply, but though his tone was grave he did not seem unduly disturbed. "Keep your eyes open, Monty. I think you will soon see land."

Some minutes passed, then Monty, watching with straining eyes, gave a sudden shout. "A light—a big light. It's away down to the right—south-east I should reckon."

"A lighthouse," responded Dick. "Somewhere on the Belgian or French coast, I expect. Give me the direction. I'll try and make it."

"But aren't you going back to England?"

"I doubt if I've got petrol. Besides, we should have to fight every inch of the way. Even down here there is a heavy westerly gale."

Monty was silent, but inwardly he was much excited. Never in his life before had he been out of England. This was a new adventure with a vengeance.

Dick spoke again. "We're almost over the lighthouse. I believe it's Griz Nez—south of Calais—but I can't be quite sure. I'm going to carry on and look for a landing. We mustn't risk damaging the Falcon."

Almost as he spoke everything was blurred again. A violent rainstorm filled the air. Monty saw that Dick, for the first time since starting, was now really worried. He himself knew that it was no joke to land in unknown country in such weather as this.

"I'm going up higher," Dick told Monty presently. "No good trying to land till it's a bit clearer."

But the rain did not stop, and though they knew that they were now far over the land, they were forced to keep going. It began to grow dark, and plainly Dick was becoming really worried.

"It's petrol," he said, pointing to the gauge.

"The tanks will be empty in another twenty minutes."

"The wind isn't quite so strong, is it?" said Monty, presently.

"No, but the weather is still as thick as ever."

"Not quite," replied Monty. "I can see lights below."

"Yes, a village, but I dare not go down yet. I can't see the ground."

The minutes passed all too quickly, and the petrol gauge sank and sank. Monty, watching it, felt desperate. Suppose they came down in a forest, and smashed their beautiful Falcon all to pieces. He had no more money to give his brother to build a new machine. It would be ruin—sheer ruin.

"Another five minutes will see us out of spirit," said Dick, frowning.

"I see lights again," replied Monty. "It's a bit clearer. Yes, and I can see big, open fields, too. Dick, it's now or never."

Dick merely nodded, and suddenly cut off the engine. The silence after the constant roar had a curiously numbing effect.

The Falcon was planing downwards and Monty breathlessly watched the dim ground which seemed to rise towards them.

Suddenly he gave a shout. "Trees just below. Look out, Dick!"

Dick switched on again, the Falcon lifted and narrowly cleared a line of tall poplars. "And a house!" cried Monty, as he caught a gleam of light. "That's better," he added. "Now there's a field. Bring her right down."

Another few seconds of tense anxiety, then the wheels touched the ground, and the big 'plane shot forward, bumping over rough grass. There was a bellowing as a herd of frightened cattle galloped away from the huge intruder. Then the pace slowed, and the Falcon came to rest.

"Splendid, Dick!" cried Monty delightedly.

But Dick was on his feet like a flash. "Quick, Monty! It's still blowing. We must anchor her firmly."

It was work they both understood well, and since the wind down here was not so strong as above, they had soon made a good job of it. The next question was to find out where they were.

"There's the house," said Monty, "the one we just missed. Let's go and see who lives there. Luckily we can both talk a bit of French."

Dick agreed, and leaving the 'plane, they made their way through the darkness across the field, and presently arrived at a tall wall. "Must be' a regular château," said Monty. "I wonder where the gate is."

They groped along the wall for some distance, and struck a big iron-studded door. There was an old-fashioned bell with a chain, which, as Monty pulled, gave a hoarse jangle. Instantly came a tremendous deep-mouthed baying.

"Sounds like a mastiff," said Monty. "I say, Dick, what have we struck?"

"Something out of the Middle Ages," replied Dick. "I only hope the brute is tied up."

There was a long delay before at last they heard bolts being pulled back. The big door swung open, and the light of an old- fashioned candle lantern showed them a tall, skinny-looking man of between forty and fifty, who wore a rusty black suit, and peered at them suspiciously with beady eyes deep-set under shaggy brows.

"What do you want?" he demanded in French.

"We are English airmen," responded Dick, in the same language. "We have been driven down here by bad weather, and we should be glad to know where we are, and where we can get a night's lodging."

"You are boys—children," retorted the other. "You are not airmen."

Monty got red, but Dick kept his temper. "If you don't believe us, perhaps you will walk with us across the field and see our 'plane," he replied courteously.

The man scowled. "You wish to trap me," he snarled.

"Oh, don't be silly," snapped Monty, now really cross.

It was at this moment that another voice was hoard. "Who are they, André? What is the trouble?"

The speaker had just come to the door of the tall, old- fashioned house, which the boys could dimly see at the end of a paved walk about thirty yards from the gate. He was a bigger man than André, but was lame, and propped himself with crutches.

André turned. "They say they are English airmen driven here by storm, Henri. But I think they are thieves."

"Bring them here that I may see," ordered the other.

The other grumbled beneath his breath, but obeyed. As the boys came up the path, suddenly an enormous mastiff sprang up and hurled itself on Monty. It was chained, but the chain was long enough for the brute to reach the path.

The force of the huge dog's leap knocked Monty down, and but for Dick next moment its teeth would have met in his throat. Quick as a flash Dick caught hold of the chain and gave it such a terrific jerk that it turned the dog right over on its back. Before it could recover, he had seized Monty and dragged him out of reach.

The elderly man, who seemed to be the master of the house, came hobbling forward on his crutches.

"That was well done. I trust the boy is not hurt." Then he turned on André and rated him well. "It is your doing that the kennel is placed so close to the path. How often have I told you to keep it out of reach?"

André did not answer, but his ugly, skinny face was one scowl.

"You must forgive my brother," said the other to Dick, speaking with a pleasant courtesy. "He is always afraid of burglars. My name is Javelot, and I am glad to see you. Now come in, both of you, and tell me what I can do to serve you."

Inside, the house was much more pleasant than out. The old gentleman took the brothers into a big, handsomely-furnished, high-ceilinged room, where a log fire was burning, and a table ready laid for supper. He made them sit down, and listened with the greatest interest to their story, which Dick told in plain and simple words. Luckily his French was good enough for this purpose. When Dick spoke of the immense height to which the new Falcon had risen, Monsieur Javelot's eyes fairly glowed with excitement.

"But how did you breathe at such a height?" he asked.

Dick told him of the enclosed body of the Falcon, and of the peculiar construction which enabled those within the body to withstand the rarefied air and intense cold of the upper levels.

Monsieur Javelot leant forward, breathing quickly. It was clear that he was not only interested, but also intensely excited. Monty wondered inwardly what the reason could be.

"But this is wonderful," exclaimed the old Frenchman—"most wonderful! And for mere boys to invent and fly such a marvel! It amazes me!"

He was evidently going to say something else when the door opened and a hard-featured woman came in with a large tray loaded with dishes.

"Supper," said Monsieur Javelot. "You will be hungry, my young friends. Let us eat. Afterwards we will continue our conversation."

The supper was excellent. There were soup, roast chicken, with exquisitely-cooked vegetables, and dishes of stewed fruit, with rich yellow custard. The boys, who were both very hungry, did justice to the good things. The man called André, who, the boys discovered, was Monsieur Javelot's half-brother, ate with them, but never said a word. He looked sulky and upset. Afterwards he helped the woman, who was his wife, to clear the table.

Then Monsieur Javelot made the boys sit over the fire, and began to talk again. He asked them about their plans, whether they meant to put the new 'plane on the market, and showed that he knew a good deal about aircraft.

His keen eyes fell upon the curious scar on Dick's hand.

"Pardon me," he said, "but that must have been a bad injury."

Dick shrugged his shoulders. "All in the way of business, monsieur. I got that the first time I ever handled a 'plane. She was an old war 'bus and went wrong, and started to nose-dive. The other chap and I had a pretty nasty half minute, and were lucky to get off with our lives."

Monty broke in quickly. "He's not telling you half of it, monsieur. One wing crumpled and the 'plane nose-dived right down upon a lake covered with skaters. It looked as if the machine would smash the ice and drown half of them. And Dick was handling her for the first time in his life. Dick kept his head, and somehow managed to flatten her out a bit and swing her into the trees on the right bank. Frank Saunders, who was with Dick, told me it was the quickest, cleverest bit of work he had ever seen in his life."

"Oh, that's all rot, Monty," said Dick, colouring. "It was the only thing to do."

"It was fine—splendid!" declared M. Javelot.

"But tell me, Monsieur Vince, what do you mean to do with this wonderful new machine of yours?"

Laughingly, Dick told him that he and Monty hoped to make money, and then go exploring.

All the old gentleman's excitement returned. "You would explore? Ah, but of course, for you are English!" He paused, gazing at them, and they noticed that, in spite of his age, which must have boon about sixty, his eyes were bright as a boy's.

"Tell me," he said, "would you explore a country less known than any other in the world?"

"Why, of course," replied Dick. "That is just what we want to do."

"But it would be dangerous—very dangerous."

"We'd take our chances," answered Dick, in his quiet way. "But what country do you mean?"

The other looked at him as if he would read his very soul.

"The Unknown Continent," he said. "The great Antarctica."

Dick started slightly. Monty's eyes widened.

"Could we do it?" asked Dick, doubtfully.

"Yes—in that marvellous machine of yours which laughs at cold or rare air."

Dick nodded. "It might be possible," he said, slowly.

"But of course it would be possible," replied the other. "And no other test could so perfectly prove the powers of your machine. Listen to me. The one who is dearest to me in all the world, my only son, he is lost in that vast desert of ice." His voice shook slightly, but he went on. "Lost, yet something tells me he is not dead. And you—you two will find him for me. Is it not so?"

Dick and Monty stared. The proposal seemed crazy—impossible. Before either could think of a suitable reply the door opened, and André put his sour face round the corner. "It is your bed-time, brother."

Monsieur Javelot turned upon him and spoke with a curt anger which was in startling contrast to his recent mood. "I am busy, André. When I want you I will call you. Meantime, leave me alone."

André did not obey at once, but stood scowling fiercely. Then, growling something under his breath, he withdrew. Monty whispered to Dick, "Mark my words, Dick. That chap means mischief."

"HE is a little troublesome, that brother of mine," said Monsieur Javelot to the boys as André retired growling like an angry dog. "But he is devoted to me. He and his wife take care of me since the accident which lamed me. You will excuse him."

The old gentleman was so charming that Dick and Monty would have done more than that to please him, and said so.

He smiled at them, then suddenly turned serious. "And now, my friends, to go back to what I was saying. This venture—this search—will you undertake it?"

"We should like to hear more about it, first, monsieur," said Dick, frankly.

"But, certainly. I will tell you. My son, Anton, is a doctor and a clever scientist. It was as doctor that he was engaged to go with the Delange Scientific Expedition to the Antarctic. That was in the year 1914, just before the Great War. It was in 1916 that the party returned to France, but Anton—alas!—was not with them."

The dear old gentleman paused, and choked a little. The two boys waited silently till he could continue.

"It was the Count Delange himself who came to me and told me the whole story. Anton, he said, volunteered for an expedition across the great ice-cap which, as you know, covers the whole of that vast continent. He went with three companions, and their object, so the Count told me, was to investigate a volcano of which the smoke had been seen from a high peak near the coast.

"Three weeks later, Anton's three companions returned and told their chief that Anton was lost. It appears that the party gained a point within a few miles of the spot from which the smoke rose. But the curious point is that there was no mountain. The smoke or vapour rose from a crevice or valley in the ice itself. They had encountered very severe weather, and were all exhausted.

"But Anton, being the strongest of them, volunteered to go forward, alone, and investigate. Through their glasses they watched him tramp across the ice until he became a mere black dot in the distance. It seemed to them that he actually reached the edge of the rift and disappeared over it.

"Then suddenly one of the terrible storms which are called blizzards swept down from the south and instantly all sight of him, the smoke and everything was lost in the whirl of ice flakes. The storm lasted three whole days, at the end of which the three survivors struggled back more dead than alive. After that the weather prevented any further attempts to discover the mystery of the smoke or to search for my son."

Again Monsieur Javelot stopped, unable to say more, and for a time the silence was broken only by the snapping of the flames of the wood fire.

It was Monty who spoke at last. "But, monsieur," he said, softly, "do you think there is any hope of Anton, your son, being still alive?"

The old gentleman fixed his eyes on the boy.

"Yes," he said, emphatically. "Yes. You may think me crazy, but in my dreams I have seen him again and again. And always he seems to be looking for me and for his old home."

"But there is no food in that Antarctic Continent," insisted Monty. "It is not like the Far North, where there are Eskimo and seals and musk oxen. Explorers say that there is no life at all on the Antarctic ice-cap."

"That is true. They all say so. Yet who knows? Not the thousandth part of that great waste has ever been explored. Smoke or vapour means heat, and with heat there might be herbage—animals—anything."

Monsieur Javelot paused. "And even if Anton is dead," he went on, presently, "I wish to know it definitely. I wish his body to be found."

Dick spoke up. "We will help you if we can, monsieur," he said, quietly.

Monsieur Javelot's bright eyes shone. "I thank you, my boy. That is all I ask."

Again there was silence for a time in the big warm room.

Monsieur Javelot moved and stretched his thin hands to the fire. "Messieurs," he said, quietly, "I am a rich man. I can afford to hire a ship and crew fit to take you and your aeroplane to the edge of the eternal ice. I shall also wish to pay you fairly for your trouble. If I am able, and my doctor will allow, I shall accompany you. You agree to my plan?"

"Certainly we do," replied Dick, "but don't you think that you are taking us rather on trust? You know nothing about us except what we have told you. You have not even seen our machine."

Monsieur Javelot smiled his very pleasant smile. "That troubles me not at all. I have eyes, and I know men. I can see that you are English gentlemen, and that satisfies me.

"But it grows late," he continued, "and you are tired. I shall now take you to the room which I have had prepared for you. To- morrow you will show me your flying machine, and we shall make further arrangements, and you shall communicate with your friends in England."

Dick shook his head. "There will be no need for that, monsieur. My brother and I are alone in the world. Our parents are dead, and we are entirely at your service."

"Alone, just as I am," said the old gentleman, softly, and rose from his chair. Monty hastened to hand him his crutches, and he led the way out of the room.

"But our machine," said Dick, rather anxiously. "It is out in the field, monsieur. Can we not house it somewhere?"

"I had forgotten," said their host. "No, I have no building large enough for it. But the wind has quite fallen, the barometer is rising, and no one will meddle with it. Is it not safe where it is?"

Dick nodded. "In that case it will be all right, monsieur. We will leave it where it is."

Lame as he was, Monsieur Javelot insisted on showing them their room, and very comfortable it was.

Then he bade them sleep well, and left them.

"A dear old chap," said Dick, warmly.

"One of the best," agreed Monty, "but I can't say I like that fellow André."

"He is rather a queer fish," allowed Dick; "but I say, Monty, aren't we in luck? Fancy, what a chance to try out the Falcon. And such a splendid trip, and costing us nothing."

"On the contrary, we get paid," said Monty. "But it's a funny business altogether."

The two turned in, but it was a long time before either got to sleep.

Once Monty got to sleep, he usually slept for a good eight hours, so it was with rather a shock that he suddenly found himself sitting bolt upright in pitch darkness. He glanced at his wrist watch, which had a luminous dial, and saw that it was not quite three o'clock.

"Now what on earth woke me up like that?" he wondered, and next instant he knew. Some one had passed the door of his room. A board had creaked. He listened hard. Another creaked. Some one was moving cautiously down the passage.

Like a flash Monty was out of bed. The room was not quite dark, for the blind was up, the window open, and there was enough starlight to see objects dimly. Silently Monty gained the door, and cautiously opened it a crack.

There was a light outside. A man carrying a small lantern was creeping downstairs. It was André, and he was fully dressed.

Suspicion flared up in Monty's brain, and on the instant he made up his mind to follow. It was the work of a few seconds only to pull on his trousers and coat. Then in his slippered feet he left the room and crept down the stairs. He heard the key turn in the lock of the front door, and reached the hall just in time to see André open the door.

MONTY waited till André was well outside before following. Luckily the door opened quietly, and leaving it on the latch he got out in time to see André passing out through the gate in the wall.

Monty's heart beat hard as he followed. He had not the faintest idea what André was after, yet instinctively felt that there was something wrong. He was in a horrid fright that the big clog might hear and start barking, but seemingly the kennel had been moved, for there was no sign of the ugly brute. A minute later Monty was outside, and cautiously following the glimmer of the lantern across the field.

The barometer had not lied. All sign of the storm was gone, and the stars shone clearly in a cloudless sky. There was a breeze, but a very light one.

And now as he saw the direction in which André was going Monty's heart began to thump. For the man was making straight for the spot where the Falcon was moored.

What could he be after? As Monty tiptoed onwards his brain was busy with this problem, but could find no answer to it.

Through the starlit darkness Monty saw the Falcon looming up like a white ghost. André had almost reached the machine. Monty, suspecting he hardly knew what, watched him keenly. André was there, he was climbing up into the body. Monty grinned. The air-tight door was, he knew, not only closed but locked, and the key in his own trouser pocket. André would have a job to get in, if that was what he was after.

By this time Monty had pretty well come to the conclusion that André was simply inquisitive. He probably wanted to see what the 'plane looked like. Perhaps, too, he was anxious to find out all he could about the visitors, and thought there might be papers or letters inside the body.

Still watching, Monty saw the man try the door, but, fading to open it, come climbing back down to the ground. He crouched low, and Monty could not make out what he was at.

All of a sudden the light of his lantern seemed to grow brighter. There was a sudden flare which showed André's face up clearly. And its expression was so ugly and savage that for the moment Monty was badly startled.

The blaze shot up so suddenly that Monty saw it had nothing to do with the lamp. It was a mass of oily rag or paper which the man had lighted. Next moment he had flung it right upon the 'plane.

With a yell of horror and amazement, Monty hurled himself forward, and racing for the spot leapt upon the framework, and seized the blazing mass. Heedless of burns, he flung it aside and it fell, flaming, to the ground. So quickly had he acted that the woodwork on which the torch had fallen was only scorched. No real harm was done.

Panting, Monty dropped back, and turned to tackle André. But the man was gone. There was not a sign of him. It was as if he had vanished into thin air.

"The brute!" gasped Monty. "So he was trying to burn the Falcon." He stamped the fire out as he spoke, then as the last spark was extinguished felt that he had been a fool. If André was still about, the man might creep upon him out of the darkness, and attack him. Then he remembered the key, and climbing up, unlocked the door and went inside. He found a big spanner and crouched there, ready for anything that might happen.

But nothing did happen, and the quiet night was unbroken by any sound.

At last Monty ventured to move and make himself more comfortable. The night air was chilly, and he put on a heavy pilot coat. "And now I'll jolly well stay here till morning," he said to himself.

Suddenly his nerves went tense, and his grasp tightened on the wrench.

Some one was coming. He crept to the door and looked out. Sure enough, there were footsteps coming hurriedly across the grass towards the 'plane. The night was so quiet, he could hear them plainly. "Surely the beggar can't be coming back?" he exclaimed to himself.

"Monty, Monty! Are you there?" It was Dick's voice in a sharp whisper.

"You, Dick?" exclaimed Monty, in astonishment.

"Yes. Who was it who was playing the fool with the 'plane?"

"It was that pig, André," replied Monty, as Dick came up.

"André!" Dick's tone showed that he was simply flabbergasted. "You're crazy, Monty. It was André told me."

It was Monty's turn to be amazed. "Of course it was André," he replied, sharply. "Why, I followed him out of the house, all the way here, J and was just in time to stop him from setting fire to the 'plane."

"But it was André who woke me not five minutes ago, and told me that you were out here after some chap who, he believed, was interfering with the machine."

By this time Dick was with Monty in the enclosed body of the 'plane. He had switched on an electric lamp, and in its white light the two brothers stood, gazing at one another. For the moment Monty was too amazed to answer, but it did not take him long to recover.

"I've got it," he cried, sharply. "It was a dodge to get you out of the house. Having failed to burn the 'plane, that was his next idea. My word, the old scoundrel is smart."

Dick's eyes were still wide. He looked hopelessly perplexed. "I'm still all at sea, Monty. What's the fellow after?"

"It's as plain as a pikestaff, Dick. André, for some reason of his own, is jealous of us. He doesn't want his brother to have anything to do with us. Tell you what—I'll bet you a bob that, if we go back, we shall find the outer door shut and locked against us."

Dick was silent. He was evidently trying to sort things out. "But Monsieur Javelot is the owner of the place," he objected. "He can do as he likes with his own house and money."

"You've hit it at once," replied Monty, quickly. "It's the money that André is after. By Jove, I see it all. Now that the old man's son is dead, André is, most likely, the next heir. The idea that his brother might use all his fortune in trying to find his son is what's upsetting André. That's why he's trying to get rid of us."

"But it's so futile," objected Dick. "Even if he has locked the door against us, as you say, we've only to wait until morning, and then Monsieur Javelot himself will let us in."

"Will he?" said Monty. "I don't know so much about that. Remember the poor old boy is lame, and I very much doubt if they'll let him out of the house at all."

"Well, let's go and try the gate," said Dick.

"You can. I'm going to stay here."

"For that matter, André is in the house, and probably in bed," said Dick. "All the same, perhaps you'd better stay here. I'll go back."

He went off and disappeared in the darkness. Monty had not long to wait, for in about five minutes his brother was back.

"You are perfectly right, old man. The door is locked, and though I rang for all I was worth, there was no answer."

Monty merely nodded. "I think we know just about where we are now. Well, I suppose we'd best wait till morning, then find the nearest town, get some petrol, and fly back to Boltham."

Dick stared at his brother. "You're not serious, Monty?"

Monty laughed. "Of course I'm not. I was only pulling your leg, Dick. If friend André thinks he's got the better of us he's precious well mistaken. Why, bless you, I'd camp here a month rather than let him score off us in that silly way."

Dick laughed at his brother's speech, but then turned serious. "We mustn't despise the fellow, Monty. A chap like that can make himself horribly unpleasant. Now, since we can't get back into the house, let's get some sleep here. We can be quite comfy for the rest of the night."

Monty agreed, and rolling themselves up in their coats they lay down.

Dick was almost asleep when Monty sat up sharply. "I say, Dick, here's a go. I'd quite forgotten till this minute, but all my clothes, except my trousers, and coat and my slippers are still in the house."

MORNING dawned fine, but decidedly cool, and though inside the closed body of the Falcon the boys were snug enough, Monty found, when outside, that his costume was far too cool for comfort.

They washed in a pond, made breakfast off some remains of food which they had brought with them from England, and at about seven sallied out.

Just as Monty had predicted, the gate in the garden wall was locked, and pulling the bell brought no reply. "Bet old André's cut the wire," said Monty.

"Quite likely, I should think," said Dick, in his serious way. "We'd better walk round the wall, and see if there is any other way in."

Monty glanced at his brother. "I say, haven't you brought a stick or anything?" he asked.

"What—to tackle André?" said Dick, with some scorn.

"No, you juggins, to tackle the dog."

"I'd forgotten the dog," confessed Dick.

"Well, I haven't. And I've got a dose for him all right."

Dick asked no questions, and the two went on round the wall. The place was bigger than they had thought. The wall enclosed more than an acre of ground. It was eight or nine feet high, and topped everywhere with broken glass. A nasty thing even to try to climb.

"There might be a tree," said Dick.

But there was no tree, and the job seemed hopeless.

Monty set his teeth. "I'm going to get over, if it takes a week," he vowed. Then suddenly he gave a sharp exclamation. "What's this? A ditch. No, a little brook, and look, Dick! It comes right out from under the wall."

Dick's eyes brightened, and he jumped quickly down into the narrow channel, which was half hidden by tall grass and weeds. Bending double, he pushed forward.

"Good egg, Monty!" he said presently, in a low, quick whisper. "We can get through."

It took a bit of squeezing, but they did it, and presently Monty put his head up, to find himself inside the wall. The ditch drained a good-sized pond, which was evidently used to water the garden. He looked carefully round.

"It's all right, Dick. No sign of André," he said. "We'd best make straight for the front door. If we go to the back we might run into Mrs. André."

Dick nodded, and both climbed up out of the ditch. As they did so there was a sudden rush, and out of the bushes near by the big mastiff came with, a silent fury that was most alarming.

"All right, Dick!" sang out Monty, and leapt between Dick and the dog.

As he did so, he thrust his hand into his pocket, and brought it out filled with black dust, which he flung full in the brute's face.

The result was amazing. The dog went up in the air as if it had been shot, and coming down began running round in circles, howling, and every now and then digging its nose into the earth.

"Heavens, Monty, what have you done?" gasped Dick.

"All right, only a little pepper," chuckled Monty. "Do him no real harm—just teach him to keep his teeth to himself."

"Arrêtez!"

The voice came from just behind the boys, and both jumped round to find themselves face to face with André. The man's mean face was twisted with rage, his deep-set eyes glowed, and his lips, drawn back, showed his jagged teeth. He was not a pretty sight. But what was much worse than his looks, he was carrying a gun. A dreadful, rusty-looking old blunderbuss, probably fifty years old, but still a gun, and as both triggers were cocked, evidently loaded.

The two obeyed the order, and stopped very short indeed. André stormed at them in rapid French, yet not loudly. It seemed as though he were afraid of being overheard. Still there was no mistaking his meaning, which was that they were to make themselves scarce at once, if not sooner.

He intimated that they were to go out the same way they had come.

"No, we will go by the gate," retorted Dick, speaking in French.

Monty spoke up. "No, Dick, we'll go by the ditch."

Dick glanced at him quickly, caught the slightest possible wink, and realized that his resourceful young brother had something up his sleeve.

"You go first," said Monty, very quietly. "I'll follow."

Dick began getting down into the ditch. He went slowly as if he was stiff and lame, and when he got down into the ditch paused, and began to remonstrate, vowing that it was a very difficult place to get through and that he could not do it unless André turned his gun away.

Just as Monty had hoped, the Frenchman grew more and more angry. He stamped, shouted, and threatened, and finally, turned his back on Monty in order to try and force Dick into the passage under the wall.

It was exactly what Monty had been waiting for. One spring, and he was upon the man. Flinging all his weight against him, he forced him right over the edge of the ditch, and down he went, head foremost, into the mud and water at the bottom. By the mercy of Providence, the dreadful old gun failed to go off, and next instant it was buried in the mud, with its owner on top of it.

Dick could move quickly enough when necessary, and this time he did not waste a second. Almost before André was down he was on him. Down came Monty, too, and between them the wretched André never had a chance.

"I've got his hands," said Monty. "Your handkerchief, Dick. Tie him!"

"Look out! You'll drown the fellow."

"Good job if I did, but don't you worry about that. Tie his hands behind him. Then we'll lift him out."

It was done, and André, completely helpless, was lifted out of the ditch. He was soaked, and was covered with mud from head to foot, especially his face, which was so plastered with black slime that there wasn't much of it visible.

"Pretty picture, isn't he?" remarked Monty, scornfully.

"I hope it will be a lesson to him," said Dick, in his grave way.

"Bah, you'll never teach a chap like that anything!" replied Monty. "Now, what are we to do with him?"

"There's a garden house over there. We can put him inside and leave him till we've seen Monsieur Javelot."

Monty nodded. "That's the ticket. We mustn't let his wife get on to it. She's liable to make trouble."

Between them they dragged the man to the garden house and dumped him in among the rakes and hoes. He glared at them, but remained silent.

"What a man!" said Monty, as they locked the door and left him. "Bet I was right, Dick,and that he and his precious wife are after the old man's money."

"I shouldn't wonder," allowed Dick, quietly.

The two moved towards the house. They were careful not to show themselves, for as Monty had said, André's wife was likely to be on the look-out. They made for the front door, and got there without interruption.

The door was closed and locked, and the boys exchanged glances. Then Monty signed to Dick and moved on towards the sitting-room windows, which were to the left. Monty's quick eyes had spotted that one of these was open. He peeped in, and pointed.

There was Monsieur Javelot sitting by a small fire. His head was sunk between his shoulders, and he looked sad, old, and dejected.

Monty whistled softly. Monsieur Javelot looked round, and an expression of utter amazement widened his eyes.

"You!" he said, breathlessly. "But no, I am dreaming."

"Not much, monsieur," replied Monty quickly. "May we come in?"

Without waiting for a reply, he pushed up the sash, and scrambled in, and Dick followed.

By this time Monsieur Javelot had his sticks and was on his feet.

"Good morning, monsieur," said Monty, cheerfully.

"Mais—mais je ne comprends pas—I do not understand," gasped the Frenchman. "I—I was told that you had run away in the night."

"By André Tissot, I presume, monsieur," said Monty.

"Y-yes—by André."

Monty paused a moment. It seemed brutal to destroy the old man's trust in his half-brother, yet it had to be done. And perhaps the sooner, the better.

The boy turned suddenly grave. "Monsieur Javelot," he said, "last night I heard a sound, and, getting up, saw your brother leaving the house. I followed him. He went straight to our 'plane and tried to burn it. Luckily I was in time to stop him. He ran back to the house, told my brother a lying story, and got him out of the place. Then he locked the gate against us. This morning we got in under the wall. He set the dog on us and faced us with a gun. Luckily we were able to trick him, and at present he is tied up in your garden house."

MONSIEUR JAVELOT had listened in a state bordering on stupefaction. As Monty ceased speaking, the old man's knees gave way under him and he dropped back into his chair.

"But it is incredible!" he gasped. "It is beyond belief. Why should André behave in such a fashion?"

Monty took him up quickly. "Monsieur," he said, "to whom does your property go at your death?"

Monsieur Javelot's jaw dropped. "I—I—to my son, of course," he answered.

"But suppose—suppose that your son is no longer alive?" said Monty, quietly.

A new light seemed to drawn on the old man. "Then—then—it is André."

Monty nodded. "And if you spend your money on finding Anton, André gets so much the less. Is that not so, monsieur?"

Poor Monsieur Javelot was quite overcome. He could only nod. But there was lots of pluck in the old chap, and presently he pulled himself together and sat up straight. "You are right, Monsieur Vince. I see it all now. I have been living in a fool's paradise. Without doubt André has been grinding his own axe. But now you have opened my eyes, and I give you my word I shall not close them again easily." He paused, then went on: "André shall leave. He and his wife, both, they shall leave at once. I will tell them so."

He struggled to his feet again.

"Then I think we will accompany you, monsieur," said Dick, with sudden briskness. "André, it is true, is in no condition to make trouble, but his wife will most certainly do so."

The words were hardly out of Dick's mouth before the door burst open, and in bounced Madame Tissot. She was fairly flaming, and poured out a perfect torrent of abuse upon the boys. They were good-for-nothing vagabonds. They had robbed the house, broken into it, assaulted her husband, killed him. They were trying to steal Monsieur Javelot's money. There was nothing too bad for her to say.

Monsieur Javelot waited with admirable patience until the angry woman paused, literally breathless.

Then he spoke, and his voice had a ring in it which the boys had not heard before. "The boot is on the other foot, Amélie," he said. "It is you and your husband who are trying to rob me. No, do not deny it, for it is useless. I have proofs. You and André will leave this house to-day—at once! Go and pack your things. You hear me!"

Madame Tissot opened her mouth again, but only to gasp. She was literally beyond speech. For a moment she glared furiously at Monsieur Javelot and the boys, then, whirling round, rushed out of the room.

After breakfast Monsieur Javelot was quite himself again, and full of ideas for the expedition. He said he would hire a ship at Marseilles and sail straight for the Antarctic. He intended, he declared, to try to find an English ship, with a captain accustomed to navigate among ice.

When breakfast was over—not before—the boys sallied out and released André. The man knew he was beaten, and said nothing. But his face was that of a panther behind bars. After they had seen him and his wife off the premises, Dick turned to Monty. "That man means mischief," he said, quietly.

Monty nodded. "Yes, but his teeth are drawn, Dick. I don't think he can do us any harm now."

"I don't know. I hope not," responded Dick. "But I can tell you this, I'm not going to take any chances."

Monty glanced in the direction where the Falcon lay like a great yellow bird with wings asprawl across the grass. "You mean about the Falcon?"

"Just so. I'm going to get her under cover just as quick as ever I can."

"You'd best stay and watch her," said Monty. "I'll go and get petrol. Monsieur has a pony and trap, and he has told me the way to the village. I'll go off at once and bring back enough to take her under cover."

"Find out where the nearest shed is, big enough to hold her," said Dick. "If there isn't one near, we shall have to get her inside the garden wall. But that would be a precious awkward job, and we should probably smash up monsieur's garden."

Monty nodded. "I'll fix it up," he declared.

Presently Dick saw him jogging off. The gate was locked behind him, so even if André should come back, Monsieur Javelot was safe for the present. All the same, Dick had an anxious time, waiting, and was only too grateful when at last he saw Monty driving back, with the trap loaded up with petrol tins.

He drove right across the field to where the Falcon lay, and jumped down quickly. "Great luck, Dick," he exclaimed. "There's an old aircraft camp left over from the war, at Joinville, only eight miles away, and the préfet of the town says we can use one of the hangars. Monsieur Javelot had given me a note to him, and he was civil as pie."

Dick smiled. "Well, the war did us some good," he observed. "I think I'll take her over there at once."

But Monty shook his head. "Not yet, Dick. You've got to give monsieur a trial flight. He's mad to go."

Dick whistled softly. "All right," he said. "You'd better fetch him in the cart, while I fill up."

Monty nodded and turned the pony. Dick had barely got his tank filled before his brother was back, and with him Monsieur Javelot, wearing a thick coat, and with his bright eyes shining with excitement.

"Have you ever been up before, monsieur?" asked Dick, as he helped the other up into the car.

"Not I! But it is never too late to mend, or to ascend," smiled Monsieur Javelot.

"It is a little alarming, the first time," Dick warned him, as he put him in a comfortable seat next the window.

Monty, having unharnessed the pony, and turned it loose to graze, followed them into the car. Dick started up the engine, and next minute the big machine was rushing across the field. She lifted just in time to escape the fence, and rose with amazing swiftness.

Dick glanced at Monsieur Javelot. So far from being frightened, he was gazing downwards, with an expression of absolute delight on his thin face.

Presently he turned to Monty. "Oh, it is magnificent!" he cried. "I can forget my lameness. I feel as if I had wings. I should like to fly all day."

Up and up Dick drove his wonderful machine until, within a few minutes, hundreds of square miles of the lovely country of France were in view beneath them. Monsieur Javelot sat entranced, and so delighted was he that Dick went higher than he had at first intended. He drove the Falcon right up through the fleecy clouds into the blaze of cold sunlight above them.

It was nearly an hour before he at last turned to descend, and by that time the frost was thick on the windows of the 'plane, yet inside the electric heaters kept her warm and comfortable. Then came the long silent swoop as the Falcon volplaned down from the heights. For a few minutes she was wrapped in dense mist as she swirled back through the clouds. Then with a cry of delight! Monsieur Javelot pointed downwards.

"There is my house!" he exclaimed. "Right beneath us. Monsieur Monty, how wonderful a pilot is your brother!"

Monty did not answer. There was a look of surprise, almost of alarm, on his small brown face.

"But there is a crowd at the gate," he said, sharply. "What are all those people doing there, monsieur?"

Monsieur Javelot stared downwards, and his expression, too, changed.

"I do not know. There must be something wrong. See, they are trying to break down the gate."

"Look out, Dick!" shouted Monty to his brother. "Switch her on again. There's something on down below, and I'll lay that scoundrel André has something to do with it."

"YES, it is André," declared Monsieur Javelot, gazing downwards. His face hardened as he spoke, and there was a curious glitter in his keen eyes.

"Tell you what, monsieur, we had better go off to the aerodrome at Joinville," said Dick.

"These people are in an ugly mood."

"No!" snapped back the old Frenchman. "I will not run away from my neighbours. Put me down among them. I will talk to them."

Monty glanced at him admiringly. "That's the ticket!" he cried. "Down with her, Dick!"

In a moment the big 'plane had reached the ground, landing so lightly that there was not the slightest jar. The moment she came to rest the crowd swung round, and came running towards her. There were some twenty men, most of them armed with sticks or pitchforks. André led them, and by their angry faces it was plain that he had been filling them with lies.

"There, I told you so! They have kidnapped my poor brother!" he shrieked.

"Death to the thieves! Death to the scoundrels!" roared the crowd.

There was a very ugly tone in their threats, but Monsieur Javelot did not seem to care a pin. He was up and out with wonderful quickness for a man as lame as he.

"Stop!" he cried, sharply, raising his hand with an arresting gesture. "Stop! You have heard André. Now hear me. Have I not as good a right to be heard as he?"

"No! The Englishmen have bewitched him!" shrieked André at the pitch of his voice. "Do not listen to him!"

But a big, bull-necked fellow stepped in front of André. "Be quiet, little man," he ordered. "As Monsieur Javelot says, it is but fair that we should hear what he has to say."

His great roaring voice smothered André's shrill scream, and for a moment there was silence.

Monsieur Javelot did not lose his chance. "My friends," he said, coolly. "Are you not a little ungrateful? It was English airmen who helped us to beat the Boche. Now it is English airmen who have promised to help me to find my dear son, Anton."

"To find Anton!" broke in the big man. "This is news to us."

"It would be," replied Monsieur Javelot, with quiet scorn. "It is not to André's interest to tell you the truth, which is that he desires to secure all my money, and is therefore angry that I spend some in the effort to find my boy."

The big man frowned. "This puts a new face on the matter," he said.

"The true one," replied Monsieur Javelot, quickly. "Am I not at liberty to do as I please with my own money? Must I ask André before I spend it? What say you, Jules Breguet?"

"No," said the big man. "That would be absurd."

"It is all a lie!" shrieked André. "I only wish to save my brother from being robbed by these good-for-nothing adventurers."

Monsieur Javelot swung round on him. "You are a good judge of truth, are you not, André?" he said, scornfully. "You who swore falsely that you were over age when you were called upon to fight for France against the Boche."

André went white. He staggered.

"Is this true?" growled big Breguet. "But yes, I can see by his face that it is true." Turning, he caught André by the collar of his coat. André lost his nerve, ducked, wrenched himself away, and ran for it. In a moment the whole crowd were after him.

"Stop!" cried Monsieur Javelot, but it was no use.

"They will kill him!" groaned Monsieur Javelot. Dick heard, and like a flash started up the plane again. He drove her along the ground, and in a moment had cut in between André and his pursuers.

"Get hold of him, Monty!" he shouted, and checked the speed a little. As the 'plane swept by, her wheels rushing over the close turf, Monty, clinging to the framework, managed to grasp André and pull him up.

"I've got him!" he yelled, and Dick, putting on speed, rose into the air. André shrieked with terror, but by this time Monty had dragged him into the body. Here the wretched man collapsed, and lay shivering, trembling with fright, while the Falcon fled through the air towards the Joinville aerodrome. There they came gently to ground again, but André was so terrified by his first flight that he could hardly stand.

His half-brother spoke sternly. "André, I am sadly disappointed in you. You have forfeited all right to share in any money of mine, but I remember that you are my relative, and I will not leave you and your wife to starve. I shall instruct my lawyer to pay you a hundred francs a month, but only on condition that you trouble me no more. You understand?"

"I agree," said André, sullenly, and the miserable man slunk away.

Monsieur Javelot spoke again. "And now I think we will go back," he said, quietly. "I shall have many letters to write. At my age one does not wish to waste time, and it is my desire to set out on our expedition as soon as possible."

Monty smiled. "Then why waste time writing letters, monsieur? Would it not be best to see the ship-owners and people personally?"

Monsieur Javelot gazed at Monty in surprise. Monty explained. "You could be in Paris in two hours if you wished," he remarked.

Monsieur Javelot gave a little gasp. "And they talk of English people being slow!" he exclaimed. "You take my breath away, Monsieur Monty." He paused. "It shall be as you say," he continued." But first I must go home and pack a few necessaries. Then this afternoon we will go to Paris."

"Right!" said Dick, in his quiet way, and started off.

It took but a few minutes to get back, and when they arrived at the house the crowd was gone. One man, however, was left. It was the big Jules Breguet, who was still chuckling over the way in which the boys had switched André out of trouble.

Monsieur Javelot was fond of the big, good-natured fellow, and asked him to stop to lunch. Since André and his wife were gone they had to cook for themselves. Breguet took a hand, and turned out a capital omelette which they all enjoyed. While they ate, they talked over their plans, and Breguet listened with interest.

"A ship!" he said. "You want a ship? But you have come to the right shop. I"—he smote himself on his great chest—"I can tell you of a ship. My son, Jean, is aboard the whaler Penguin, which has just arrived at Brest. She is an English ship, and her captain, Monsieur Bates, is an Englishman."

"That sounds good!" exclaimed Monty, eagerly. "But is she for charter?"

"I do not know," replied Breguet; "but my Jean, he has written to me that the whaling is a failure and that he is to be paid off. It seems likely that the owners would be glad to do business."

"It does, indeed," put in Monsieur Javelot, as eagerly as Monty himself. "Say, now, my friend, will you telegraph at once to your son and ask him?"

"But of course I will, and it may be that you will take him—Jean—with you?"

"If the ship suits, we certainly will," declared Monsieur Javelot. "Wait now, and I will write the telegram."

He did so, and Monty went off with it at once. Then they waited impatiently for the reply. It came before night:

PENGUIN IS FOR CHARTER. AM LEAVING FOR HOME TO-NIGHT TO GIVE ALL DETAILS. —JEAN BREGUET.

Monty gave a whoop of joy, and did a war dance round the

table. "Our luck's in!" he exclaimed. And Monsieur Javelot smiled

and said he really believed it was.

Next day Jean Breguet arrived. He was a stocky, dark-haired fellow with a straight look in his eyes which pleased the boys at first sight. He was second mate of the Penguin, and knew the ship "inside out." She was of six hundred tons, schooner rigged, with oil-driven engines. She was only about eight years old, staunch and seaworthy. Jean had got the terms of contract in his pocket, and they were not too high. In an hour the whole thing was settled, and a cable sent to the Penguin's owners at Hull, offering a definite charter.

"And now we have got to get busy," declared Monsieur Javelot. "Jean, you and I shall go and see Captain Bates, and between us arrange for fitting out the ship. Monsieur Dick and his brother will go to London, and there procure what matters they require for their part of the journey."

Though lame in body, there was nothing wrong with Monsieur Javelot's brain, and the energy which he displayed was simply amazing. Next day he found a caretaker for his house, and the whole party left, he and Jean by rail for Brest, and the boys in the Falcon for England.

Well supplied with money, they had no difficulty in getting all the spare parts and equipment they required. They worked like fury, and so apparently did Monsieur Javelot. Within a fortnight the Penguin was ready for sea, with the Falcon dismantled packed safely between decks.

"ICE! Ice in sight!" Monty came flying down the companion into the main cabin of the Penguin where Dick was sitting, deep in a book dealing with Antarctic exploration. "Ice, Dick!" he repeated, eagerly. "A thundering great berg! Come and see!"

Dick followed his excited brother.

"Ugh, it's cold enough, anyhow!" he grumbled, as they emerged on deck. The Penguin, with all sails set, was running before a brisk nor'-westerly breeze, with her bows pointed due south. They had passed Gough Island, and were in latitude 42 degrees south.

Dick stared at the great mass of ice which his brother pointed out—a huge berg with blunted pinnacles rising a hundred feet or more against the pale blue sky.

"A good bit of difference between south and north, eh, Monty?" he said.

"How do you mean, Dick?"

"Why, we're only about as far south as Madrid is north. Lucky for old England that ice doesn't swim in 42 degrees north."

Monty nodded. "I'd never thought of that."

"You will have plenty of time to think about it," broke in another voice, a deep, hearty one, and Captain Bates came up to where the two brothers were standing. The skipper was a short man, who looked even shorter than he was by reason of his tremendous breadth. He had a forty-two-inch chest, enormous physical strength, a square jaw, and a temper which it took a good deal to disturb. "From this on we shan't often be out of sight of ice," he continued. "Beastly stuff!" he added. "The more I see of it the less I like it."

Bates's prophecy proved a true one, and within three days after passing the first berg the Penguin was meshed in a tangle of ice-fields. Still, there were plenty of channels, and the skipper, who had had years of experience of ice, managed to keep the ship moving always towards the south.

They were a long way south of Bouvet Island before they got into real trouble, for here they found their way south blocked by an ice-field so gigantic that even from the crow's-nest they could see no end of it either east or west. Captain Bates turned eastward, and coasted slowly along the edge of the field, hoping to reach the end. Instead, he found that the field swung northwards, leaving them in a sort of bay with ice to the south and east.

It was beautiful weather, almost dead calm, and the sun's rays were reflected with dazzling brilliance from the endless fields of floe ice. The sea itself was a vivid green. Everything looked lovely, but Captain Bates did not enjoy these beauties. His question was whether to turn round and steam all the way back westwards, or wait where they were in the hope that a wind might come and break up the ice-fields.

Since it was necessary to economize in fuel, he eventually made up his mind to wait.

Monty, who was always as keen as mustard, made the suggestion that they should get out the Falcon and fly high enough to get some idea of the size of the ice-field, but Dick vowed that this was out of the question, because of the difficulty in rising and landing.

Monty's next discovery was that there were seals on the ice, and he begged Captain Bates that he and Dick might be allowed to go and shoot them.

The skipper smiled. "Well, I was going to send a boat to get some snow to melt down for fresh water. Yes, you and Dick can go. But you must take Jean Breguet with you. He knows the ice, and you don't."

Monty was full of excitement, and rushed off to get a rifle. A boat was lowered, and with Breguet and three other men and the boys in it, was pulled across to the floe. As they came near the ice Monty fell silent. The scene was really too wonderful for words—the barrier of glittering ice stretching mile upon mile in each direction, the water calm as glass except for the slight swell, lying there black under the shadow of the floe, the intense silence, the only sign of life being the beautiful little snow petrels flitting like snowflakes through the sun-bathed air.

It was a bit of a scramble to get on to the floe, for the edges were thin and rotten, and the boys would have got a ducking but for Jean, who first broke away the edges with an iron bar and then helped them up.

Once on the floe the going was good enough. Monty looked about eagerly for the seals. There they were, but so far off that they looked mere black dots on the gleaming surface. They lay about two hundred yards in from the edge of the floe.

"Why do they go so far from the water?" Monty asked of Jean.

"Zey are not so far as you sink," replied Jean, who spoke English with a strong French accent. "Zey 'ave zeir own blow 'ole in ze ice. Ve must be vair careful, or zey vill jump down 'im."

Monty nodded. "You lead the way, then," he said.

Jean went down on all fours, and the two boys copied his example. The stalk was long and difficult, for there were cracks here and there, which they had to cross or go round. In spite of the chill of the ice, the sun was hot, and they were soon, all three, dripping with perspiration. The only comfort was that the seals did not move, and Monty began to have pleasant visions of fresh seal liver fried with bacon for breakfast.

At last Jean stopped behind a small hummock. They were now within about a hundred yards of the seals, but between them and the animals the ice was all flat and open. "I sink you 'ave to shoot from here," he said. "If we go nearer, zey vill run away."

Monty hastily loaded his rifle, and so did Dick.

"Quick!" muttered Jean. "I give ze word. Zen you both shoot at once."

The two boys lay down and took careful aim, one at the left-, the other at the right-hand seal.

"Now!" said Jean, and the two rifles cracked as one. Dick's seal went over, quivered slightly, and lay still, but Monty's went off full pelt across the ice.

"Missed!" snapped Monty, firing again. But the second bullet went high, and they saw it cut the ice and ricochet out to sea. Next moment the seal had vanished—no doubt into its air hole.

"Well, you've got one anyhow, Dick," said Monty, concealing his disappointment, and he and the rest went hurrying across the ice towards the dead creature.

They had nearly reached the spot, when suddenly a seal, apparently the one that Monty had missed, shot out of the water at the edge of the ice, and, landing on the floe, came flapping towards them at amazing speed.

"What the mischief—" began Monty, then stopped, gasping.

For out of the water, just where the seal had made its jump, was suddenly thrust the most grim and terrible head ever seen outside a nightmare. Black as a boot, it looked as if carved out of solid rubber. Its front seemed square, but gashed with an enormous mouth armed with sharp, ivory-like teeth, each about four inches long.

"Did you ever see such a brute?" gasped Monty, and was starting forward again, when Jean's strong fingers closed on his arm. "Stop! It is ze killer!" he cried.

"Killer—what do you mean?"

"Ze killer whale. Ze wolf of ze sea. Keep vere you are!"

"Why, what's the matter? A whale can't walk on the ice."

"No, but ze whale can break ze ice."

The words were hardly out of his mouth before the whole floe quivered with a fresh shock, as the mighty killer leapt again, and, falling with all his giant weight on the edge of the pack, broke away a great mass of it. Then suddenly, close behind him, a second and a third monster rose out of the glassy sea, and after more—a dozen at least in all.

The mighty killer whale leapt again, falling

on the edge

of the ice, which gave way under its enormous

weight.

"Run, run!" cried Jean. "Back on ze thick part! Zey 'ave smelt us!"

Almost as he spoke, there was a crash right under their feet; the floe broke, and a spout of water dashed up. The shock flung them all to their knees, and through the turmoil of broken ice and spray they plainly saw the head of another killer bursting into view.

MONTY felt himself slipping forward into the hole made by the rush of the sea monster. He struggled desperately, but in vain. Then Jean's powerful hand gripped him, and in the very nick of time drew him back.

"Up! Get up quickly!" he heard him cry, and somehow he struggled to his feet, and he and Dick and Jean together went stumbling over the heaving ice.

Thundering blows crashed on the bottom of the floe beneath them, and the ice quivered and cracked as though an earthquake were shaking it. Monty felt as if it must all break into fragments under such a terrible bombardment. The whole thing was like a bad dream, and he did not believe it possible that they could escape alive.

"Further, a leetle further," Jean was calling in his ear. "Do not despair. Ve shall be safe soon."

Monty did not believe him for a moment, but the mere blind instinct to try and save his life drove him on. More than once he fell flat on the ice, bruising himself badly, but he stuck to it bravely, and somehow managed each time to regain his feet and struggle on.

A ridge lay in front of them. They scrambled over it, and all of a sudden the terrible racket seemed to die away and the swinging floe to steady under their feet.

"Zere, I did tell you. Ve are all right," said Jean, triumphantly.

"About time, too. I'm blessed if I could have gone much farther," panted Monty. "But where have the brutes gone?"

"Ze ice is too thick for zem 'ere," Jean answered. "Zey know zat zey break zeir 'eads if zey try to butt here."

Monty turned and stood gazing at the strip of floe which they had just crossed. The whole of it was simply in fragments. It was broken to pieces, and through the cracks the sea-water was gushing and heaving in fountains.

"They've got our seal," cried Monty, angrily.

"Don't grouse, Monty," said Dick, drily. "Just be thankful they haven't got us, too."

"It vas a close shave," said Jean, gravely. "I told you zey was ze wolves of ze sea."

"Wolves crossed with elephants," growled Monty. "Heavens, Dick, I've heard of killer whales, but I always thought they killed other whales. I never knew they came out of the sea after people."

"Zey vill go anyvere," replied Jean, gravely. "Lucky it ees for men zat zey 'ave not got legs."

"Or wings," added Dick. He paused. "They certainly are the most savage brutes I ever saw or heard of. I'm sorry for the poor seals."

"One of zem killers, he vill eat three seals for his breakfast," Jean told him. "But look! Zey 'ave seen us from ze ship. Zey send ze boat for us."

Sure enough a boat was coming off, but the man in charge was pulling for a spot on the edge of the ice-field, a long way off. Jean started towards it, and the boys followed him.

"I say, do they ever attack boats?" asked Monty, uncomfortably.

"I do not sink so," replied Jean. "I 'ave never 'eard of zat."

Apparently he was right. At any rate there was no more sign of the killers, and the party reached the ship in safety. Monty, for one, was very thankful to feel the firm planks of the Penguin's deck once more beneath his feet.

Monsieur Javelot came up full of excitement. "Ugh, but it was terrible!" he exclaimed. "My heart was in my mouth when I saw those monsters attacking you."

"It was entirely thanks to Jean that we got away from them, monsieur," replied Monty. "But all's well that ends well, and we're none the worse. I expect you got the biggest scare," he added, with his engaging grin.

"That is true. I was terribly frightened," replied Monsieur Javelot. "Do you know I actually ran across the deck."

"You couldn't have done that six weeks ago, monsieur."

"You are right. I am marvellously better. I do not know whether it is hope or whether it is the effects of the voyage and the change of air and scene, but I am mending. I am better than at any time since my accident. And I feel—" he paused and spoke more gravely—"I feel that the finding of Anton will make me quite well again."

Later Monty spoke to Dick. "Dick, the old gentleman really believes that he is going to get his son back."

Dick nodded gravely. "We must do our best."

"But do you think there is any chance? Honestly, Dick, do you?"

"I don't know, Monty. I don't know. But somehow Monsieur Javelot's faith makes me feel that it may be possible."

"I do hope so," said Monty. "If he is disappointed, if we don't find anything, I think it will kill the poor old dear."

Just then Jean came up to them. "Ze captain, 'e say ze glass fall," he announced. "If ze vind come, he break ze ice."

Monty whistled softly. "Let's hope the ice is the only thing it will break. I don't quite fancy the idea of a gale down in the middle of all this stuff."

But the barometer did not lie, and next morning, early, Monty was roused by a roar only to be compared with that of heavy guns. Dressing quickly, he and Dick hurried on deck to be met with a blast that nearly took their breath away.

Great waves were dashing on the floe which was cracking with a noise resembling vast peals of thunder. Already the sea was full of masses of broken ice, and the Penguin, with steam up, was holding away from the edge of the floe, awaiting her chance to proceed southwards.

Monty felt a trifle nervous, but Captain Bates was cool enough, and Monty was encouraged by his example. All day the gale blew furiously, and by ten at night, when the wind began to fall, the great ice sheet was broken everywhere, and the long lanes of open water pierced it in every direction.

The skipper lost no time in pushing the Penguin straight through the barrier. By morning they were in clear water again, and then were able to hoist sails and speed southwards before a favouring breeze.

Day after day they had fine weather and a favouring breeze, while, though they constantly saw huge icebergs, they met no more large sheets of floe ice.

"I never saw these seas so clear," Bates told them. "It's the biggest luck we've ever had. There must be a good fairy at our tow rope."

As they sailed farther and farther south the days grew longer, until at last there was no darkness at all, and at midnight the sun still showed red just above the southern horizon. But in spite of the long day, it grew very cold, and the boys were only too glad of the warm woollens which they had laid in when in London.

At last, three weeks after sighting the first berg, they came on deck one morning to see the horizon bounded by a tremendous wall of ice.

Captain Bates called them on to the bridge. "There," he said, as he pointed, "you're looking at what mighty few men in this world have ever seen. That is the great Ice Barrier, the edge of the Antarctic Continent."

Monty was breathless with excitement, and Dick, in his quiet way, was equally impressed.

"Where are we going to land?" demanded Monty, eagerly.

The skipper smiled and shook his head. "That I can't tell you. We are within twenty miles of the place where the Delange Expedition landed, but it does not follow that we can land at the same spot. The ice in the Antarctic, just as in the North, is shrinking, and a spot where you can land one year may be sheer cliff a year or two later. However, we shall know more about it before nightfall."

After a while Dick went down to breakfast, but nothing would induce Monty to leave the bridge.

Every minute the great ice wall grew clearer. It was a lovely day, with brilliant sun, and the rays reflected from the ice dazzled the eyes. As the ship came nearer the scene became fairy- like. The cliffs, sheer blue ice, towered in many places two hundred feet or more above the floe ice at their foot, and they were full of great hollows where the shadows lay azure and purple. Immense icicles hung from the cornices, sparkling like diamonds.

A few seals lay upon the floes, and skuas and snow petrels were seen. In the open water big whales rose, blowing spouts of vapour from their nostrils. These were what interested Captain Bates more than anything else.

"Never saw such a lot," he said, "or so tame. Why, bless me, there's a fortune in sight, in blubber alone!"

Picking their way through much floating ice, some of it towering bergs, about ten in the morning they reached a large semicircular bay which cut three miles or more into the Antarctic Continent. Behind it were blunt mountains rising two or three thousand feet against the pure cold blue of the sky.

"This is Delange Bay," announced the skipper, and putting his glasses to his eyes, carefully examined the shore.

Monty watched him with breathless interest.

"Yes," said the captain at last. "I think I see a possible landing-place."

"Hurray!" cried Monty. "Our luck holds." Just as he spoke Dick came up. He was dusty and dirty, and there was a very grave look on his good-looking face.

"I'm not so sure about that, Monty," he said gravely.

"Why, what's the matter?" cried Monty.

"I have been down in the hold," said Dick, "and I have just made the unpleasant discovery that some one has tampered with the petrol. I have opened a number of tins to find them filled, not with petrol, but water."

"HAVE you told any one?" demanded Captain Bates, curtly.

"Only Monsieur Javelot."

"Then tell nobody else," ordered the skipper. "And what does Monsieur Javelot think?" he added.

"That it is the work of that half-brother of his," replied Dick, gravely.

Bates nodded. He had, of course, already heard all about André Tissot, the scoundrelly half-brother of Monsieur Javelot, who had tried to stop the expedition. "It seems likely," he answered in a low voice, "though how he could have managed it is a bit hard to say."

"Do you think he could possibly have bribed any of the crew?" cut in Monty, quickly.

"You have put my thoughts into words," said the captain. "That is what we must find out. We must also find out whether all the petrol tins have been treated in the same way."

"We had better do that at once," said Monty. "If we have no petrol it is no use even landing. Come on, Dick!"

The two brothers hurried off, and with Jean's help set to ferreting out all the cases of petrol which were stored in the fore-hold. Case after case was opened, and their faces grew longer as they found that all had been treated in a similar fashion. They held water instead of petrol.

Just as they were beginning to despair they came upon some steel drums, and it was with shaking hands that Monty unscrewed the cap from the first of these. An unmistakable odour of petrol arose, and Monty quickly dipped out some of the contents into a tin, and carrying it to a safe spot, put a match to it.

To his intense relief it blazed up, and further tests showed that it was good petrol. Soon they were certain that the drums at least had not been tampered with, and both sighed with relief.

But Dick was not happy. "We have only enough for a flight of three or four hundred miles," he said, "instead of at least two thousand. It's a bad job, Monty."

But Monty refused to be downhearted. "The place isn't more than two hundred miles inland, and we shall spot it by the smoke. Don't you worry, Dick. We shall be all right."

They went and told Monsieur Javelot, and though he had been much upset by Dick's first discovery, he quickly regained his spirits. "We shall have enough," he declared. "It will be all right. Something tells me so." Then suddenly he stopped and frowned heavily.

"What's the matter?" asked Monty.

"I was thinking of André. I was regretting that I have no means of stopping his allowance," replied Monsieur Javelot.

Monty laughed outright. "Don't let that bother you, monsieur. Dick and I will square with him when we get home again. Now we will go and tell Captain Bates."