RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

"The Vamp" ("Messenger's Million"), T.A. & E. Pemberton, Manchester, 1948

THE eyes of the plump, pink-faced manager of the Great Southern Bank widened as they fell upon the figures on the cheque which young Gilbert Stratton had pushed across the counter.

"ONE hundred and eighty-seven pounds and ten shillings!" he said. "Shelcott's doing well, Gilbert. Has he raised your screw yet?"

"Not he!" returned Gilbert, with a smile that made his square, brown face very attractive. "I'm still drawing three quid a week—and likely to." Tom Horner's lip curled.

"He's a stingy swine." Then a shocked look crossed his genial face, and he looked round quickly to be sure no one else was within hearing. "I oughtn't to have said that," he added quickly. "Especially as Shelcott is one of the bank's best customers."

"Don't worry," grinned Gilbert. "I shan't give you away. But some day I shall probably tell him so myself."

"I shouldn't blame you if you did," said Horner. "Why don't you chuck it, and try for something else?"

"Because I don't want to starve," said Gilbert curtly. "There aren't half a dozen clay pits in the county, and you can bet your boots that Shelcott would take precious good care I didn't get into one of them if I left him." He shrugged his shoulders. "I've just got to carry on, Mr. Horner."

While they talked the manager's fingers were busy counting notes and silver. Most of it was silver, for that was what Shelcott needed for paying his men in the clay works. The money was packed in a canvas bag, and when the whole amount was settled and checked Gilbert picked up the bag. Horner came round the counter and accompanied him to the door.

"Fog on Mist Tor, Gilbert," he said. "You'll have a bad journey, I'm afraid." Gilbert glanced at the thick grey cloud that shrouded the top of the moor.

"I've been in too many fogs to worry about 'em, Mr. Horner. But I'll get on before it grows worse. Good-bye."

"Good-bye. See you next Friday, I suppose?"

"I hope so," smiled Gilbert, as he got on the saddle of his ancient motor bicycle and dumped the bag of money in the side- car. He started up the engine and roared away. Horner watched him go.

"A real good lad," he observed. "And always cheerful. Never seems to realise what a rotten life he leads up there on top of the moor. No society, no amusement, and practically seven days' work a week." He shivered in the raw air of the November afternoon and went back into the bank.

Stout Mr. Horner might have changed his mind had he been able to watch Gilbert's face as he drove his rattling old motor bicycle over the bridge and up the steep hill beyond. The young man's lips were set and his eyes hard. These weekly trips to Taverton were the only break in the deadly monotony of life up at the Carnaby Clay works and he hated going back there as a boy hates going back to school.

In spite of the noise it made, the old bike travelled well, and presently Gilbert was entering the mist cloud, the grey fingers of which were reaching further and further down into the valleys. Here he had to switch on his headlight and drop to lower gear. He came to Slipper Hill and crawled slowly upwards. The road was cut along the side of the steep tor, and above it the hillside was strewn with boulders.

A dark lump loomed up in the misty glare of his headlight. It was a big stone lying in the very middle of the road, and Gilbert stopped at once, and got off. Though he could have passed it easily enough the stone was a death trap for any car or lorry, and in common decency it was up to him to move it. Gilbert was tough as wire; but the rock weighed at least a hundred-weight, and took a deal of shifting. He was breathless by the time he had rolled it into the gutter.

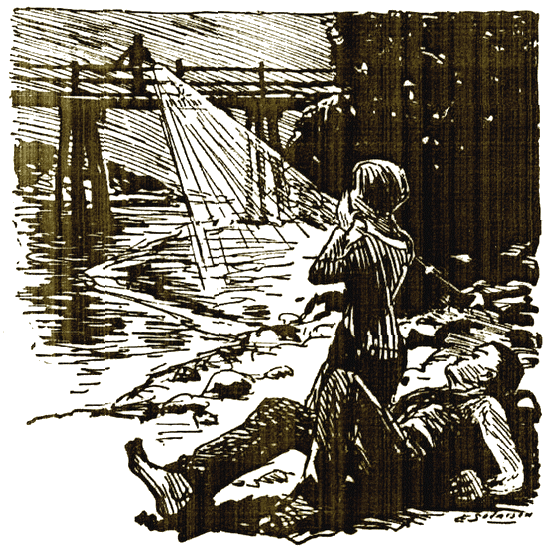

A sound behind him caught his ear, and turning he saw a man bending over the side-car. With a shout he rushed at him, but before he could reach him the man had grabbed the bag and was racing away down hill.

He saw a man bending over the side-car.

The mist was so thick that Gilbert could barely see the flying figure ahead; but he kept hard after him, and began to gain. Suddenly the man stopped, swung round, and his right hand flashed out. A small bag of pepper struck Gilbert full in the face and burst, filling his eyes and mouth. As he staggered back half choked and completely blinded, he heard a mocking laugh, then the quick rattle of boot soles on the hard road as the thief raced away.

While Gilbert stood gasping, trying in vain to clear the stinging powder from his eyes, he became aware of another sound, a quick click of shod hoofs.

"Hullo, what's up?" came a man's voice.

"A thief. He's got my bag of money," Gilbert managed to answer.

"Where did he go?"

"Straight down the hill."

"What's he done to you? What's the matter with your face?"

"Pepper—but don't mind me. Catch him if you can. He's got nearly two hundred pounds."

"Pepper—what a swine! There's water by the roadside. Here, let me lead you."

"Don't bother about me," said Gilbert sharply. "Get the thief."

"Don't worry. I'll get him safe enough," the other answered. He was already off his horse, and leading Gilbert across the road, made him kneel down and dip his hands in a little rill which ran down the gutter.

"Now you'll be all right," he said. "Stay where you are. I'll collar the blighter." Next moment he was riding hard down hill.

Gilbert, in such pain he could hardly think, splashed the ice- cold water into his burning eyes, and presently found himself able to see again. But now he was all alone. Dusk was closing down, and the raw fog hung round him like a shroud. He got to his feet and stood listening hard, but not a sound broke the clammy stillness.

"A nice mess-up!" groaned poor Gilbert. "What will Shelcott say? Odds are he'll accuse me of stealing his pay roll. He'll sack me anyhow—that's a cert." The more he thought the more unhappy he felt. Losing the sort of job Gilbert had would not worry the average young man, but, as Gilbert had told Horner, it was the only work he knew, the only thing that stood between him and the Labor Exchange. He was perfectly certain that Paul Shelcott would send him packing the minute he told him he had lost the pay roll. As for getting it back, the odds against it were a thousand to one, for in a fog like this the thief would have all the chances in the world of getting clear away.

Minutes dragged by, each seeming like an hour, and still nothing happened. Gilbert went back to his machine. He decided that he had best go straight back to Taverton and tell the police what had happened. He was in the act of turning the bicycle when he heard the klop-klop of a trotting horse, and next moment horse and rider loomed out of the smother. For a moment Gilbert's hopes soared, then when he saw the rider was alone they fell again with a bump.

"You didn't get him," he said.

"I didn't get him, but I got this." The other dropped the heavy bag with a clank into the side-car.

"You got the money?" gasped Gilbert, hardly able to believe his senses.

"Yes, and I think it's all there. The chap hadn't time to open the bag. Have a look, will you?" Gilbert picked up the bag.

"It's still sealed," he said joyfully. "I say, I'm most awfully grateful to you." The other laughed. Poor as the light was Gilbert saw him for a tall, powerfully-built young man, with a big clean-shaven face, a beaky nose, and large, prominent eyes.

"Then, that's all right." he said. "I'm only sorry I couldn't catch the blighter himself. When I got close he dropped the bag and took to the heather; and that's where I chucked it. I wasn't going to risk Belle's legs—to say nothing of my own neck," he added with a laugh.

"I'm glad you didn't," said Gilbert. "And I can't tell you how grateful I am to you for getting back the money. Shelcott well—I don't know what he'd have said."

"Shelcott—you mean the man who owns the Carnaby Clay Works? Do you work for him?"

"I've worked there all my life," Gilbert told him. "My name is Stratton. Mr. Carnaby adopted me when I was six."

"And you've lived up there ever since! Good Lord!—how do you stick it?"

"No choice," said Gilbert. "It's the only job I know."

"A pretty rotten one, it seems to me," said the other. "What do you do in your spare time?"

"Fish—and shoot."

"But don't you ever get a game of bridge or billiards?"

"I've never had the chance."

"Why, you poor devil! Forgive me. I oughtn't to have said that."

Gilbert laughed a trifle bitterly. "You can say it if you like. It's perfectly true."

The horseman looked down at him.

"Come and see me some time. My name is Merrill—James Merrill. I live at Woodend."

"I'd like to," said Gilbert gratefully.

"Well, come next Sunday. Come to lunch at one." He stretched out his hand. "All right, then. We'll expect you on Sunday. Good night."

"Good night," said Gilbert, "and—and thanks most awfully for what you've done." Merrill only laughed and rode away, and Gilbert once more in the saddle drove up hill through the fog.

"YOU'RE late," growled Shelcott, as Gilbert entered the office, and handed over the bag.

"There's a pretty heavy fog," said Gilbert quietly. Shelcott was a thick-necked, heavy-set man of thirty, handsome in a coarse way, but mean, and a bully.

"First time I knew you were afraid of a fog," he sneered.

"Only when I have other people's money to think of," replied Gilbert as calmly as before.

"Then you ought to have started earlier," snapped his employer.

"You are forgetting your order to the bank—that I'm to have the money at five minutes to four. And don't swear at me," added Gilbert, looking the other very straight between the eyes. Shelcott knew he had gone too far.

"Oh, don't be so infernally touchy," he muttered; and Gilbert, after a moment's pause, went out and up the hill to the cottage, which was all the home he knew.

The clay works lay on a bare hillside nearly fourteen hundred feet above sea level. The ugliest, barest place imaginable. A huge pit, an even huger dump, and everything whitened with chalk- like china clay. The cottages were of raw, grey granite. The country was too high and cold for gardens, and not a tree, not even a bush, broke its hideous monotony. At present the ugliness was shrouded by darkness and fog, and the kitchen of Clamp's house was at any rate warm and bright.

Clamp himself sat staring into the fire. He had a pipe in his mouth, but it was out. He was a big, powerfully-built man of fifty, and had been famous for his great strength, but had aged sadly since his son Joe had got into trouble.

Joe, a wild youngster, though with no real harm in him, had got in with a gang of poachers who had fallen foul of one of Sir John Cotter's keepers, and shot him. Joe and one other man had been caught, and though there was no proof that Joe had had anything to do with the killing, he had been sentenced to five years' penal servitude. Now, though Clamp was only fifty, his hair had gone grey and his giant frame was shrunken. Yet he smiled as Gilbert came in.

"So you'm back. Muster Gilbert." Then a look of dismay crossed his face. "But whatever has come to your eyes. Looks like ee'd caught a terrible cold."

"It's pepper I've caught, not cold," said Gilbert, and while he warmed himself he told Clamp of his experience on the way home. Clamp was horrified.

"I've heard tell of things like that in Plymouth and Lunnon, but I never reckoned no one would try it up here on the Moor. But 'ee saved the money."

"Mr. Merrill saved it for me. Who is he, Clamp? Do you know anything about him?"

"Not a deal. They do say he'm a sporting sort o' gentleman. And he'm got a proper pretty sister."

"A sister," repeated Gilbert blankly. "I didn't know that."

Clamp looked surprised.

"What difference do it make to 'ee, Muster Gilbert?"

"He asked me to lunch."

"'E'll go?" said Clamp. Gilbert shook his head.

"Not if he's got a sister."

"And why for not?" demanded Clamp, looking straight at the younger man.

"How can I?" asked Gilbert bitterly. "I don't know how to talk to girls. I've never met any—never had anything to do with them." Clamp stiffened.

"You'm talking moonshine, Muster Gilbert. You'm just as good as they. You'm a gentleman born, even if you was raised up here on the Moor. Now you'm a chance to mix it with your own kind, you go on and take it." It was the first time Gilbert had ever heard Clamp take this tone, and he was so astonished that he could find nothing to say.

"Now you go and bath your eyes," Clamp said, "and then come to supper. It's nigh ready."

Gilbert went meekly to his room, and came back presently to a meal of boiled bacon and greens, followed by an apple pasty and cheese. There was strong black tea to drink. He helped Mr. Champ to wash the dishes, then sat and smoked a pipe with Champ, and at nine he went off to bed. In summer he would go fishing, but all through the winter his evenings were spent in exactly the same way.

There followed another day's work. Even on Saturday Gilbert got little time to himself, for there were always accounts and letters. Sunday came at last, and Gilbert put on his one decent suit, a rather worn blue serge, which Mr. Champ had pressed and brushed for him. At twelve, he set off to walk to Woodend, which lay in the Valley of the Awne, about three miles from the quarry.

It was true enough, what he had told Clamp. At twenty-three he had hardly ever spoken to a girl of his own class. His parents had been killed in a railway accident when he was six. They had both been only children, so there was not an aunt or an uncle to take the lonely child; and if it had not been for Gilbert's godfather, old Mark Carnaby, Gilbert himself must have gone to the workhouse. Carnaby had taken him in, brought him up, and sent him to the Taverton Grammar School, where he had stayed till he was fifteen, and got a very fair education. Then the old man had gone down with pneumonia, and died within forty-eight hours; and when he was dead it was found that he had left no will, and that the pit and everything went to his unpleasant nephew, Paul Shelcott.

Paul had disliked Gilbert from the first, and would have sent him about his business only that he knew how unpopular this would make him. He did the next worse thing, took him away from school and turned him into an office drudge; and for seven long years Gilbert had done two men's work for less than one man's pay. Paul still disliked him. In fact, his feeling had grown to hate because he no longer dared bully him. Yet he would not dismiss him, because he knew he would have to pay double the money to get anyone half as good.

All these years Gilbert's life had been no better than that of a quarry man—worse in fact, for none of them were as lonely as he. There were girls of course at the clay pit, and more than one would have been kind to Gilbert if he had given them a chance. But there was something in Gilbert's make-up which saved him from that sort of thing.

And now, at last, Gilbert was going to meet a woman of his own class, and who can wonder that he fairly shivered with shyness and nervousness as he found himself walking up the drive to Woodend? Woodend was a small place, but with its trim flower- beds, its greenhouse and stables, it looked imposing in Gilbert's eyes. Merrill met him at the door. He was wearing a plus-four suit of red-brown tweed. His stockings matched his knitted waistcoat, and his tie and handkerchief were both of dull green silk. He looked big, sleek, and prosperous.

"Come in, Stratton. Very glad to see you," was his cordial greeting. "What about a cocktail? You must need one after your walk." He drew Gilbert into what he called his study, a snug room with very few books, but a quantity of sporting prints. Fishing rods were in racks on one wall, and a pair of fine hammerless guns in a glass-fronted case. Decanters and glasses stood ready on a small table, and presently Gilbert found himself drinking a pleasant but potent mixture—the very first cocktail of his life.

"Well, of all the selfish people—haven't you mixed one for me, James?" The rich, deep voice brought Gilbert sharply to his feet, and he stood gazing, almost staring at the girl who had entered the room.

Ida Merrill was tall, but not too tall, and exquisitely slim. Her skin was cream, her hair dark copper, beautifully waved. Her eyes—Gilbert thought they were green, but could not be quite sure. She brought with her into the room an atmosphere of intense femininity. Small wonder that Gilbert stood amazed.

"My sister," said Merrill, and Gilbert found himself holding the slim hand of this vision, blushing like a schoolboy and quite unable to say anything coherent.

"So you are Mr. Stratton," he heard her say. "James told me about your adventure the other evening. How perfectly thrilling!"

"The thrill was a perfectly beastly one—for me," Gilbert managed to say. "If I'd lost the pay roll I should have been in a most awful hole. I'm frightfully grateful to your brother."

"And so am I," said Ida, with a laugh, "for adding a young man to my visiting list. Most of the people about here are old and stodgy beyond belief. But there's the gong. Come to lunch. I'm sure you're hungry." She led the way into the dining-room, small, but, like all the rest of the house, extremely comfortable. The table was of old black oak polished like a mirror, so that the silver was reflected in it.

Such food Gilbert had never seen, let alone eaten. Clear soup, grouse, with chipped potatoes and stewed celery, an ice pudding and a dainty savoury. For drink, hock, and afterwards a glass of excellent port. Thinking of it later, Gilbert was full of wonder, for somehow his shyness was forgotten and he found himself talking quite easily, telling his host and hostess of his work at the clay pit, of his shooting and fishing and fifty other things. He did not realise that Ida had set herself to draw him out; nor her tact in avoiding all talk of things such as theatres and music, of which he was quite ignorant.

After lunch James went to his study, but Ida took Gilbert into her own sitting-room, where a fire of logs kept out the chill of the autumn day, and gave him cigarettes of a quality hitherto unknown to him. Time simply flew, and Gilbert was quite startled when the pretty silver clock on the mantel chimed four.

He jumped up.

"I must go," he said. Ida did not move.

"Trying to be polite?" she mocked. Gilbert did not know what to say. She laughed.

"Sit down, you silly boy," and when he still hesitated, she stretched out her arm and pulled him down beside her. "I can't help it if you're bored."

"Bored!" cried Gilbert horrified. "I—I've never enjoyed myself so much in my life."

"Then stay where you are and don't be silly," said Ida. "I shall be horribly bored if you go."

"Do—do you mean that?" Gilbert asked, stammering a little in his earnestness.

"Of course I mean it." She laid her I hand on his, and he thrilled at the touch. And just then the door opened.

"Mr. Shelcott," said the neat maid. Gilbert was so amazed he sat stock still. Ida rose leisurely to her feet.

"So it's you, Paul?" she said languidly. "You didn't tell me you were coming to-day. You know Mr. Stratton."

"I ought to, seeing he's my clerk," replied Shelcott, glaring unpleasantly at Gilbert.

"Well, I'm sure he's a very good clerk," replied Ida, "and he's been telling me all sorts of interesting things about the Moor and your workpeople."

"He knows them better than I do. He lives with them," sneered Shelcott. Gilbert realised the man was jealous, and the knowledge gave him a curious feeling of confidence.

"I have to, you see," he said quietly. "I can't do anything else on three pounds a week."

"Three pounds a week!" repeated Ida. "Paul, you ought to be ashamed of yourself." There was a nasty gleam in Paul Shelcott's eyes as he glanced at Gilbert. But he managed to smile.

"We shall have to see about a rise—especially since e's got into society," he added, in a tone that brought the blood to Gilbert's cheek.

Before anything more could be said the maid brought in tea, and an awkward situation was saved. James Merrill came in and talked business to Paul. So for the next hour matters were smooth enough on the surface, then Gilbert got up and said good-bye. Ida went with him to the door.

"You'll come again," she said. "Come next Sunday," she added, in a voice too low for Shelcott to hear. "Will you?"

"I shall love to," said Gilbert fervently.

As he tramped back up hill through the chill dusk of the autumn afternoon, he felt extraordinarily elated, yet at the same time a little puzzled. Gilbert Stratton was no fool, and he could not help wondering a little why these people had been so kind to a youngster like himself without money or prospects, or even a decent suit of clothes. And while he considered this point he heard a car coming up behind, and suddenly there was Shelcott's smart two-seater stopping alongside.

"Get in," said Paul harshly.

"Thanks," said Gilbert easily, "but I'd rather walk."

"Get in. I want to talk to you."

Gilbert smiled.

"I know you've nothing nice to say to me. Suppose we wait till Monday."

Shelcott got out, and came across.

"We'll talk now," he said ominously. "How did you get to know the Merrills?"

Gilbert kept his temper. "Is it any business of yours?" he asked quietly.

"Curse your cheek! Is that the way to talk to your employer?"

"You're my employer six days in the week, but not on Sunday," returned Gilbert briefly. Two spots of red showed on Shelcott's thick cheeks, his eyes had a nasty glitter.

"If you're not jolly careful you won't be in my employ much longer. Are you going to tell me how you came to know the Merrills?"

"No," said Gilbert curtly. Shelcott's temper went to the winds.

"Then you're sacked. You're sacked. You hear me?"

"I can't well help it when you shout like that," replied Gilbert. "And don't make faces at me. I don't like it."

"Make faces!" bellowed Shelcott. "Why, curse you, you dirty little charity boy—" That was as far as he got, for anything further he had to say was stopped by Gilbert's fist, which caught him neatly, between the eyes, and sent him staggering back against his car. Gilbert stood ready, but all the fight was out of Shelcott. He leaned against the car with his handkerchief pressed to his bleeding nose, and glared savagely at Gilbert.

"You shall sweat for this," he said in a voice of concentrated venom. "If I've any influence in the clay trade, you shall never get another job in it. And since it's the only work you know, you'll starve. And I'll watch you starve."

Gilbert's anger passed, and he shivered slightly. He knew that Shelcott was right, and that he could make good his ugly threat.

"HE'VE sacked you?" Old Clamp's voice and face both showed the dismay he felt at Gilbert's news.

"He's sacked me all right," said Gilbert. Then he grinned. "But he'll have a sweet pair of black eyes tomorrow."

"Did 'ee hit him?" asked Clamp eagerly.

"Only once," replied Gilbert regretfully. "He wouldn't fight."

Champ chuckled.

"I wish I ha' been there to see," he said; but Gilbert shook his head.

"Jolly good thing you weren't, Champ, or you'd have got the push as well."

Champ sat back in his wooden chair and put his clay pipe between his lips.

"He'm a fule," he said. "He'll never get no one to do your job for twice the money."

"I'm not worrying about him," Gilbert answered. "My worry is a new job for myself, and I'm hanged if I see where I'm going to find one. China clay's the only thing I know about; and Shelcott wasn't boasting when he said he could stop me getting in with any of the other firms. He has a lot of influence in the trade."

Clamp shook his grey head.

"You'm right, Muster Gilbert. And he'm venomous as a twoad. Like as not he'm writing round to 'em this minute." Gilbert gave a short laugh.

"You're a bit of a job's comforter, Clamp. All the same I'm not going to starve just to please Paul Shelcott. I'm fairly fit, and if nothing else turns up I'll take on as a roadman. I can crack stones with the next." Clamp looked shocked.

"Don't 'ee talk that way, Muster Gilbert. Your father's son can't do work like that. Tell 'ee what—you go and see Muster Horner. He'm a nice gentleman, and can give 'ee better advice than I can." Gilbert's eyes brightened.

"That's not half a bad notion, Clamp. Tom Horner is just the one man I can go to for advice. I'll push off first thing In the morning and see what he has to say."

Just then Mrs. Clamp came in to say that supper was ready, and in spite of all his excitement and his good luncheon Gilbert ate his share of a cold pasty with good appetite. But when bedtime came it was a long time before he could sleep, and when he did at last drop off his rest was disturbed by queer dreams. Ida's beautiful face and Shelcott's angry one drifted through his subconscious mind. He was glad when dawn came and he could turn out and sluice himself in icy cold water and wash out these queer, unpleasant visions. Mrs. Clamp stared at him when he came down to breakfast in his better suit.

"I'd forgot," she said soberly. "It don't seem possible as 'ee ain't going to work to-day, Mr. Gilbert."

"Don't worry about me, Mrs. Clamp, I won't be out of work very long. I'm off this morning to find a new job."

"But it won't be here, Mr. Gilbert," she answered sadly. "And father and I—we'll miss 'ee terrible."

Gilbert put his hands on her shoulders said kissed her lined face, and for a moment or two the poor thing broke down and sobbed.

"You'm almost like a son to us, Mr. Gilbert," she said. "I don't know what we'll do without 'ee—now Joe's gone."

"Joe will come back," Gilbert told her. "And Joe will do well, and be a credit to you. And as for me, you haven't seen the last of me. Don't think it." She smiled through her tears.

"You'm not one to desert your friends, Mr. Gilbert, I know. Now come and have your breakfast."

It was a fine morning, and Gilbert decided to walk to Taverton. There was a short cut across the Moor, and he felt like exercise. There is nothing more perfect than a fine autumn day on Dartmoor. The heather bloom was over, but the gorse was still golden. Tit larks sang, and snipe rose twisting from bits of boggy ground. The pale blue sky was dappled with soft clouds, and the great hills were rich with color, brown, gold, and purple.

Gilbert came down into the valley of the Thane, where the clear amber water poured in long rushing trickles from the high hills. He made for the stepping-stones which crossed the stream above the thick coppice called Hanging Wood, and had almost reached them when, in the long pool just above the wood, a great salmon leaped high and fell back with a resounding splash. Gilbert saw it for only the half of a second, but that was enough for him to notice the gut cast flash in the sun. The big fish was hooked.

The fisherman he could not see, for he was still in the wood; but next instant out he came, a shortish man wearing rubber waders—heavy things—yet in spite of their weight he was coming at top speed. He had to, for the hooked fish was fairly racing up stream, and the speed of a salmon in the water is faster than most things on dry land.

Gilbert, keen fisherman himself, pulled up short to watch the struggle. But as if this in itself was not sufficiently exciting, all of a sudden another man came charging down out of the bushes on the steep bank opposite. He was older than the first, but bigger, much bigger. A great, gaunt-looking fellow, very roughly dressed, and Gilbert recognized him instantly as Seth Grimble, owner of Stonelake Farm, a typically old moorman, long-headed and short-tempered as any of these hillmen. He had a stiff beard, and clean-shaven upper lip, his hair was grizzled, his face was angry.

"Hi!" he roared. "What yer doin' on my land? Stop—drat ye!" Gilbert sized up the situation in an instant. All this land on the upper side of Hanging Wood was Grimble's, and no man stood more keenly on his rights than the old farmer.

As for the younger man, he did not appear to hear, or if he heard paid no attention. All his energies were concentrated on keeping up with his capture, which was still going up-stream like a torpedo-boat, and had already taken most of the line off his reel.

Grimble came leaping down on to the fisherman's path which bordered the river, and turned up it in pursuit.

"Stop, I tell yer!" he bellowed, in a voice which roused the echoes from the distant rocks. "Stop, ye derned poacher, or I'll break your blame neck."

Still the angler seemed unconscious of these awful threats; but Gilbert saw that he would soon be overtaken, and that it was time to interfere. He ran hard for the stepping stones which were just at the bottom of the pool, and crossed them in a series of bounds that would have been impossible to any one less active. Then gaining the path on the far side he raced in pursuit of Grimble.

Quick as he was, he was too late, for before he could reach Grimble the farmer had caught up with the fisherman and clamped a heavy hand on his shoulder. The fisherman, small as he was, showed that he had plenty of pluck. Pausing for the merest fraction of a moment, he swung his left leg backwards; the heel of his wader caught Grimble in the shin, and with a howl of pain the big man relaxed his bold and fell backwards into a tangle of brambles, amid which he lay, struggling frantically and roaring like a penned bull. The fisherman, without even glancing at him, continued up the bank.

The big man relaxed his bold and fell backwards into a tangle of brambles.

Gilbert reached the spot just as Grimble struggled out of the thorny tangle and regained his feet. He was badly scratched, his coat was torn; and if he had been angry before he was now in a state of dangerous rage.

"I'll skin ye for that. I'll put ye in the river. I'll see ye in Taverton Gaol." He said other things which would not look well in cold print. Then as he started afresh after the fisherman he found Gilbert between him and his prey.

"What yer doin' here, Mr. Stratton? Get out o' my light, I tell yer."

"Steady, Mr. Grimble." Gilbert's tone was quiet but very firm.

"What d' yer mean—steady? Ain't I got a right to stop a poacher on my own land? Get out, I tell yer, afore I hurts yer." He clenched his big fists, but Gilbert did not budge.

"He's not a trespasser. He's followed a fish from his own water into yours. That's allowable in sport and in law. It's you who'll see Taverton Gaol if you assault him." Grimble towered over Gilbert, but Gilbert's shoulders were broad and his eyes were steady. His cool front made the big bully pause, but he was still raging.

"Me assault him!" he roared. "Didn't he knock me into that there thorn bush? Look at my coat a-ripped to ribbands. Out o' my way, and let me get at him." Gilbert kept his place and his temper.

"You tackled him first, Mr. Grimble, and if the case does come to court I've got to say so."

"I don't care what you says. Clear out now, afore there's trouble."

"You've had trouble before," said Gilbert significantly. "What about John Betts? Grimble's arms dropped to his sides. A startled look came into his little angry eyes. Gilbert had hit him in a very tender spot, for only a year ago the farmer had been fined five pounds for beating up his pet aversion, John Betts, whom he had found on his land, but who was able to prove that he had been on the footpath.

"Tell the old josser I'll buy him a new coat," came a voice behind Gilbert. "Tell him I'm sorry I pushed him into the bush. And for any sake; lend me a hand to gaff this brute of a fish."

"There," said Gilbert; "you're going to get a new coat for nothing, Mr. Grimble. And you've got an apology into the bargain." Without waiting for Grimble to answer he swung round, grabbed the gaff which hung at the back of the fisherman's belt, and leaped lightly down the bank. The salmon, beat with its rush, was circling on the surface close in and Gilbert, waiting his chance, slipped the gaff under it, and, with one quick jerk, dragged it ashore and up the bank. One sharp crack on the head finished its struggles, and it lay on the grass, a shining bar of silver.

"Twelve pounds, if he's an ounce," said Gilbert. "And a nice clean fish. Congratulations!"

"You're a darn fine hand with the gaff," said the other admiringly, and turned to Grimble.

"Sorry I shoved you in the bush. What about that old coat of yours? A quid any use to you?"

"A new coat'll cost me two," replied Grimble sourly. The other fished out a pocket book and extracted two pound notes.

"You're a sinful old robber," he said with a grin. "But you shall have these if you'll clear out and say no more about it." Grimble grabbed the money.

"All right." he growled, and stalked off. The fisherman chuckled again. He had a round, brown, good natured face, a little tooth-brush moustache, very fair hair, and very bright blue eyes.

"You're a darn good Samaritan," he said to Gilbert; then a puzzled look crossed his face. "Don't I know you?" he asked doubtfully.

"You ought to, Bobby," said Gilbert, "We were in the same form at Taverton."

Bobby's eyes widened.

"Good gosh, it's Gilbert Stratton! Well, of all the rum chances! Put her there, old son!" The two shook hands cordially.

"What brings you here, Bobby?" asked Gilbert. "I thought you'd gone into business somewhere up North."

"So I had. So I did, and, lord, how I hated it! I was clerk to my uncle in Doncaster for four years. Then the poor old josser departed this life, and when his will was read I found he'd left me thirty thousand pounds, I nearly fainted. When I recovered I couldn't pack up quick enough. I was back in Devonshire Inside 24 hours, and here, by gum, I mean to stay."

"Where are you living?"

"At Randlestone. I've bought a jolly old cottage. I've got a retired marine called Chard, as batman, and his wife as cook. I fish, and I shoot, and I'm as happy as the day is long."

"Sounds ideal," said Gilbert quietly. Bobby fixed his blue eyes on the other.

"It don't look to me like you've had quite the same sort of luck, old son." Gilbert laughed.

"I've no kind uncle to leave me thirty thousand pounds, or even thirty thousand pence. However, I've scraped along up to date."

Bobby looked at him again. Those blue eyes of his were sharper than Gilbert knew.

"We're going to celebrate, Gilbert. You're coming home to lunch with me."

Gilbert shook his head.

"I must go to Taverton, Bobby."

"All on the way home. My little 'bus is in the lane. Come along."

"You've got your fishing, Bobby."

"I'm no hog. I've got a fish. You come and help me eat it." Gilbert hesitated.

"I must see this man in Taverton," he urged.

"You can see him. I don't suppose you want to spend the day with him."

"No, I'm asking him to find me a job." Bobby stared.

"Out of work, are you?" He grinned suddenly. "Don't worry about the gent in Taverton. I've got a job for you. Come on." He picked up his fish, and led the way to the road.

A TWO-SEATER, a sports model of a well-known make, stood on the turf at the roadside, and Robert Hilary Barr dumped his salmon into the boot, reeled up his line, unjointed his rod, put these with the salmon, and slipped into the driving seat.

"In you get, Gilbert," he ordered, but Gilbert paused.

"This job, Bobby. You'd better tell me before we start."

"I won't," said Bobby flatly. "Crawl in."

Gilbert shrugged and took his seat, Bobby let in the clutch, and the car glided away. In a moment it was flashing down the long white road with the speedometer needle steady at 40.

"Nice little 'bus, ain't she?" said Bobby. "You drive, Gilbert?"

"I can handle a bike or a lorry."

"Good egg. Then a car would be play to you. I say, it's fine to run into you again, old man. Just the one thing I wanted, to meet up with an old pal. He was so cordial, so evidently delighted at the meeting that Gilbert felt a little thrill of pleasure. His had been such a very lonely life.

"Now, tell me all about yourself," Bobby went on, and presently Gilbert found himself talking more freely than he had for years. Bobby slackened speed as he listened.

"I've heard of Shelcott," he said presently, "So you pasted him. Gosh, I wish I'd been there to see. The fellow's a rotter, Gilbert. You're well quit of him."

"Trouble is I'm not quit of him. He has a lot of influence in the clay trade, and he'll take precious good care I don't get another job in it."

"Hang the clay trade. You can do better than that, old son."

"How? It's the only work I know."

"You know office work. You can handle cars and men. Bless you, you can take a job anywhere."

"But I've no references, Shelcott won't give me any."

"Blow Shelcott. I'll give you a character. But here's the shanty. What do you think of it?"

"Topping!" declared Gilbert as he looked at the granite front of a charming old cottage which had been carefully modernised without in the least spoiling its original beauty. "And an orchard and a trout stream. My word, what a place to live in!" Bobby chuckled.

"Just what I want you to do, Gilbert. I need a pal. Take you on as my secretary. Two hundred a year and all found. What do you say?"

Gilbert stared at Bobby, He could hardly believe his ears. Then he shook his head. Bobby's face fell.

"Not enough? I'll make it two-fifty." Gilbert flung out his hand.

"Don't talk rot. Two hundred's too much—far too much. But I can't take it. Bobby."

"Why not?"

"It'd be play, not work. Don't think I'm ungrateful, but it would never do. I'd go all to pieces."

Bobby opened his mouth to protest again, but the look on Gilbert's face stopped him, He shrugged.

"Well, you'll stay a few days anyhow—as a favour, Gilbert. Hang it all, you've earned a holiday."

"The favour's mine. I'd love to."

"All right. We'll drive over and get your kit this afternoon. Now what about a spot of lunch?"

Lunch was cold roast duck and salad and a plum tart. Mrs. Chard was a first rate cook, Chard a perfect valet. Everything was nice as could be, and Gilbert thoroughly enjoyed it all. That afternoon they fetched Gilbert's suit case from the clay works, and on the way back Gilbert called at the bank and saw Mr. Horner who readily promised to do what he could to find Gilbert work.

Next day Bobby took Gilbert shooting, and on the following day, which was wet, motored him into Plymouth gave him lunch at the Grand, and afterwards they went to a matinee at the Royal.

"You're ruining me, Bobby," said Gilbert on the way home. "If I stay with you any longer I shall never be fit for work again."

"Rats!" remarked Bobby. "If a chap can't take a week's holiday after seven years' work he ought to be shot."

"I'd enjoy the holiday all the more if I knew I'd a job to go to when it was over," said Gilbert with a sigh. But Bobby only grunted. The car pulled up at Bobby's front door, and Chard came out.

"Gentleman's been ringing you up from the bank at Taverton, Mr. Stratton. Asked that you should ring him as soon as you got home."

"It's Horner," cried Gilbert, jumping out "He must have found something for me."

"Any one would think the feller actually liked work," said Bobby mournfully; but Gilbert was already at the 'phone. When he came back his eyes were bright.

"Homer's got me a job, I believe, Bobby. A man called Cowling has bought the Elford granite quarry and wants a sort of clerk- of-the-works. I'm to go up and see him to-morrow."

"Sounds pretty grim," said Bobby. "Still if you must have a job I hope you get it, for you'll only be eight miles away, and there'll be some hope of seeing you now and then. All right, I'll drive you there in the morning."

"No, I'll go on my old bike, Bobby. I don't want Mr. Cowling to take me for one of the idle rich."

Bobby knew it was no use to protest when Gilbert took that tone, and next morning Gilbert went off on his ancient, noisy, but still efficient machine, and within half an hour was climbing Elford Tor, in the side of which gaped the great raw chasm which was the Elford Quarry. Along the roadside were strung the cottages of the men, and below ran the little river Strane bubbling in the autumn sun. A workman directed him to the office, and there at a plain desk, sat the strangest, grimmest-looking man whom Gilbert had ever met. Judging by his wrinkled, parchment-like skin he was old, yet his hair was still dark and his tall, gaunt frame gave an impression of almost youthful vigor. He had a long, clean-shaven face, a thin, tight-lipped mouth, and grey eyes that were wonderfully bright and keen. As Gilbert stood in front of him he felt as if those grey eyes were fairly boring into his brain, and it seemed an age before the old fellow spoke.

"You are Gilbert Stratton?" he said in a harsh, croaking voice.

"You are Gilbert Stratton?" he said.

"That is my name, sir," replied Gilbert.

"How old are you?"

"Twenty-three, sir."

"H'm, young for the work I want. How much experience have you had?" Gilbert told him.

"What sort of character have you from your last employer?" Gilbert's heart sank.

"None, sir," he answered steadily.

Mr. Cowling's bushy eyebrows rose.

"I understand from Mr. Horner that you were dismissed."

"That is true," replied Gilbert simply.

"What was the reason?"

"Mr. Shelcott and I didn't get on, sir."

"That's not much of an answer," said the other gruffly.

"It is all I can give you," replied Gilbert.

"You can give me no explanation at all?"

Gilbert felt it was all up. He picked up his cap. The other frowned.

"What's the matter?" he asked testily. "Don't you want the job?"

"I want it very badly, sir, but of course I know that my lack of testimonials is a bar."

"That's for me to say—not you," retorted Cowling. "What money do you want?"

"I've had three pounds a week, sir."

"H'm, I give five pounds, and you can come on three months' trial. Don't stand and stare. When can you begin?"

"To-morrow—to-day if you wish, sir."

"Be here at nine to-morrow morning There are two furnished rooms over the office. You had better settle in this evening." Somehow Gilbert found himself outside.

"Well, of all the queer old beggars!" he found himself saying, and then he discovered that he badly wanted to sing. He leaped on his old bike and went roaring down the road at a reckless pace. Clamp—he must tell Clamp first. How pleased the old fellow would be! And perhaps he might meet Shelcott. He chuckled as he thought of Shelcott's face when he learned that his ex-clerk had got a new job at nearly double his old salary.

His thoughts turned to the Merrills They, too, would be pleased. And another thing, now he could afford some decent clothes. He hardly realised that it was only since this meeting with Ida that he had begun to wish to make a better appearance. After all he had sixty pounds saved up.

"I'll go to Taverton this very afternoon and order a suit," he vowed to himself.

The great mound of tailings above the Carnaby works stood up glaring white in front, and he slackened speed before turning into the side road leading to the pit. The main road and the train line were on the far side of the hill, and this was only a rough cart track cutting across the newtake, the big stone-fenced field where Shelcott's stock grazed.

As he got off to open the gate Gilbert saw a girl walking up the track ahead of him. At first he thought it was one of the pit men's daughters, but a second glance showed that she was nothing of the sort. No Carnaby girl would wear such a smart brown tweed suit, or carry a stick, or swing along so briskly as this girl was doing. Some friend of Shelcott, he supposed, as he closed the gate behind him and started to push his machine up the track. The road was too rough and rutty to risk his rather worn tyres.

At any other time a stranger to the pits, and especially one so smart, would have interested Gilbert immensely, but now he was so engrossed in his own affairs he hardly gave her a second thought. He was thinking of old Clamp's pleasure, of Shelcott's rage, while in the back of his mind he was wondering what Ida would think of his new job.

A sound roused him, a sort of explosive grunt; and glancing round in the direction of the sound he saw a great animal heaving itself up off the ground on the upper side of the field. With a feeling of acute dismay he recognised it as Shelcott's bull, Vindex, an animal of notoriously bad temper.

"The fool!" he said to himself. "What the deuce did he put it here for?"

The big brute stood for a moment with its eyes fixed on the girl. Then it began to paw the ground, flinging up great lumps of turf.

"Look out!" Gilbert shouted; but the girl had already seen the bull and had paused uncertainly. "Back—get back to the gate," Gilbert cried. But it was too late. Lowering its shaggy head the savage beast charged.

REGINALD ASPLAND'S flat in Knightsbridge was small, but charmingly furnished and extremely comfortable. Reginald Aspland was one of those big, stout, genial, selfish men who make a god of comfort. Tea was over, the curtains were drawn, and Nance Aspland, who had spent the afternoon playing golf at Ranelagh, sat in a deep chair toasting her dainty toes before a cosy fire.

Nance was rather small, but beautifully made. Her hair was brown, with a glint of gold, her face something better than pretty, for the firm chin gave hint of a character very different from that of her ease-loving father, and her eyes, very deep blue in color, were level as those of a boy. Tired with her hard game, she was lying very quiet when a queer sound from her father roused her. It was half a snort, half a swear. She looked up.

"Bills, Dad?" she asked, in a voice which proved that bills were a not unusual source of annoyance in this household.

"Bills," groaned Aspland, who was seated at his writing-table with a whole sheaf of suspicious-looking documents in front of him. "Worse than that, Nance—writs." Nance shrugged.

"You shouldn't be so extravagant."

"Me—extravagant! My dear Nance. What are you talking about?"

"Your extravagance. You went to Brighton last week-end and that didn't cost less than ten pounds. You bought two new suits and a lot of new silk shirts last week; you asked the Gunters to lunch at the Savoy when you might just as well have had them here; you—"

"Oh, stop it!" cried Aspland. "A man must live." Nance straightened.

"A man must live according to his income, and yours isn't a bad one," she stated firmly.

"What! A thousand a year. You call that a decent income?"

"It's more than ninety per cent, of people get, and it's paid you free of income tax, so it's nearly thirteen hundred."

"It's nothing to John Messenger. He has forty thousand a year, and I doubt if he spends four hundred. And I'm his heir."

"I know, and you've been living on your prospects for years," went on Nance remorselessly. "Suppose he disinherited you?" Aspland's ruddy face paled.

"For Heaven's sake, don't suggest anything so dreadful, Nance."

"Well, he might if he heard you were in debt. A man like that, who has made his own money, hates debt, and I'm quite sure he will be very angry if you get into the Bankruptcy Court, and, perhaps, stop your allowance." She changed her tone.

"Dad, you really might brace up and economise." she said earnestly. He groaned again.

"I'll try. I really will try. But everything's so infernally expensive nowadays, and these confounded tradesmen pester one's life out." He went back to his bills, and Nance, glancing at the clock, got up and turned on the wireless.

"I won't keep it on," she said. "I just want the weather forecast and the news. I'm helping Mrs. Sutton with her children's party to-morrow, and it makes all the difference if it's fine."

After a moment's silence the time-signal came through, then the voice of the announcer. "This is the National programme from London. Before the news I have two S.O.S.'s."

"Confound the S.O.S.!" growled Aspland irritably. "Why can't they put them on at some other time?"

Nance did not speak, and the announcer's voice sounded clearly through the cosy little room.

"The police are anxious to trace John Messenger, missing from his home at Formby House, Filey, Yorkshire, since October 3 last." Aspland sprang from his chair.

"Messenger!" he gasped. "Good God!"

"Hush," said Nance swiftly, and the voice went on:

"The missing man, who is well known in Yorkshire as the owner of the Messenger steel-rolling mills, is 72 years of age, six feet one inch in height, has white hair, white moustache, and a short, stiff white beard. He was wearing a suit of dark-grey cloth, a black overcoat, black square-toed boots, and an old- fashioned square-crowned hat of hard black felt. He is possibly suffering from loss of memory. Will anyone who can throw light on his whereabouts communicate with the Chief Constable, Filey, Yorkshire, telephone—or with any police station."

The voice began on the second S.O.S., and Nance cut off. He father had dropped back into his chair. All his ruddy color was gone, and his plump hands were shaking.

"What does it mean?" he asked hoarsely "And why wasn't I told? As the heir they ought to have communicated with me before issuing an S.O.S."

"I expect that was done by his lawyer Mr. Martyn, Dad; and the police have left him to tell you."

"But he hasn't done so."

As Nance spoke the telephone bell rang and Mr. Aspland took off the receiver.

"Yes," Nance heard him say sharply "Yes, I've just heard the S.O.S. Mr. Martyn called away, you say. When can I see him?" A pause, then: "All right. I will be at the office at ten to-morrow morning." He turned to Nance.

"You're right. The police phoned Martyn, and he authorised the S.O.S. I'm to see him in the morning. But what can have happened?"

"I should think they are right," replied Nance, "and that he has lost his memory."

"But a man like that—so well known—some one must have seen him." Nance frowned a little.

"You would think so. I—I'm afraid he must be dead."

"Suicide, you mean, Nance?"

"Yes, or perhaps accident. Anything may happen to an old man who has lost his memory."

For the rest of that evening Aspland was unusually silent. Nor did he go out to his club after dinner as was his custom. He was up early next morning, and at a quarter to ten was on his way to the Bedford Row office of Martyn, Martyn and Sons, who were Messenger's solicitors. Nance waited in for him, but it was nearly twelve o'clock before he returned, looking very worried.

"Martyn knows little more than we do, Nance," he told her. "He only got the news the day before yesterday. Mrs. Knight, Messenger's housekeeper, had written him and he went straight up to Yorkshire. But no one seems to have the faintest idea of what has happened. Messenger went off on the morning of Tuesday, the 3rd, saying he would be away for a day or two, and she was to carry on as usual. He didn't say where he was going, but he seemed just as usual. She did carry on until the following Monday, when, as she had heard nothing, she grew anxious and wrote to Vivian Martyn. Martyn has put the local police on the track, but the only thing that has come to light is that an old chap, who looked like Cousin John, was seen at Harwich getting on the Dutch steamer. Martyn has sent a man over to Holland, and the police are doing all they can, but so far there is absolutely no news." Nance looked troubled.

"There's nothing we can do, Dad?"

"Not a thing. But I haven't told you the worst of it, Nance," he said ruefully. "My quarter's allowance is due next week, but, as you know, old John signs the cheques himself. If he doesn't turn up I'm broke to the world."

"But you're his heir," protested Nance. "If he's dead you get everything."

"Ah, if he's dead; but that's the question. And if he isn't, but has simply wandered away, I'm done. In a case of this sort, Martyn tells me, the Courts wait something like seven years before they allow death to be presumed." His plump face lengthened. "What the deuce shall we do if we have to wait seven years before we touch a penny?" Nance considered a moment.

"There's only one thing to do, Dad," she said presently. "We must leave London and go down to The Roost. I don't suppose your creditors can touch my money, can they?"

"No, of course not, but—" His face was more eloquent than words.

"Oh, I know you'll hate it," said Nance with a little smile, "but it will be very good for you. Fresh air and plain living. It will make a new man of you.

"It will make a mummy of me in a month," groaned her father, who was miserable if he was more than a mile away from Pall Mall and his club.

"Well, ask Mr. Martyn if he doesn't think I'm right," said Nance. "Ring him up now."

"No need for that," grumbled Reginald Aspland. "Martyn always backs you. All right, I'll come. But you'd better go down first and open the house." Nance nodded.

"I'll go this afternoon," she continued. "And I'll see if I can get Mrs. Betts. She cooks quite nicely, so you won't starve. And perhaps we'll find someone to play bridge with you. Cheer up, Dad. It won't be as bad as you expect."

"It couldn't be," said Mr. Aspland in a hollow tone; and Nance left him and went to her room to pack.

Nance Aspland's mother, who had died when Nance was ten, had left her three hundred pounds a year and a cottage at Brimmacombe known as The Roost. The poor lady had had a good deal more money than that when she first married Reginald Aspland, but Nance was grateful for small mercies, and down in Devonshire three hundred pounds would at any rate keep the wolf from the door.

For a young woman whose father was up to his neck in debt, and was also in danger of losing every penny of his income, Nance Aspland was remarkably cheerful. The fact was that she infinitely preferred the country to the town. Gardening, riding, fishing, and golf were her favourite occupations, and she was never so happy as on the rare occasions when she could get away to The Roost and live an open-air life. It was but very rarely that she could ever drag her father down to Devonshire, and nearly the whole of her life had been spent in London. So, perhaps, she may be excused for thinking it only right that she should have her turn, and for wasting comparatively little sympathy on her father.

She caught the two-thirty from Waterloo, arrived safely at Taverton at seven-ten, spent the night at sedate Bedford Arms Hotel, and early next morning drove out to The Roost.

That afternoon she went in search of Mrs. Betts, only to hear that she had moved to Carnaby, where she was keeping house for her uncle. So early next morning, Nance, who was a great walker, started out afoot for Carnaby. And the walk went very well indeed until she took the short cut across the newtake road and—met the bull.

GILBERT saw the girl start running towards him. She ran like a boy, head up, hands clenched, her small feet fairly scudding across the rough grass.

But she had not a chance. Gilbert saw that the bull would catch her before she even reached him—let alone gained the gate. He jumped on to his machine, gave the starter a kick, and the engine burst into noisy life.

His first idea was to pick her up and race with her to safety; but he had hardly started before he saw that even this was impossible. There would be no time to take her up and turn before the bull caught them both. The only thing that remained was to try to draw off the racing beast.

"The gate!" he shouted as he passed her. "Make for the gate. I'll keep him busy." He spoke with a confidence that he did not in the least feel; but there was not much time for thought, for here was Vindex almost on top of him. The great beast weighed nearly a ton, and the ground fairly shook under his thudding hoofs. His shaggy head was low, and his little eyes were red with rage. With the usual single-minded devotion of his kind, he was hunting the girl, paying not the least attention to anything or anybody else.

In order to draw him off Gilbert had to get right in front of him, a risky business on such rough ground. It was all he could do to keep his battered old machine from skidding, and he had the unpleasant knowledge that his back tyre was distinctly shaky. It was worn right down to the canvas.

It was not until he had roared up almost in front of the bull's nose that the big, stupid brute paid him any attention. Then the clatter of the exhaust caused him to pause slightly. Gilbert yelled at him, and the trick was done. Turning at an angle so sharp that his great hoofs skidded, he swung, and, bellowing vengefully, was off on the track of his new enemy.

Gilbert made for the opposite gate. If only the ground had been good his anxiety would have been at an end, but it was not. This was no meadow turf, but a newtake full of heather and clumps of rush and—what was far worse—the native granite, which underlay it, thrust ugly knobs of lichen-clad rock above the surface. It took the cleverest kind of riding to dodge them; but Gilbert had ridden for years on all sorts of rough roads, and probably few professional dirt-track riders could have bested him on this sort of ground. But he had to dodge the rocks while the bull was able to go straight. The pace at which the great brute travelled was simply amazing, and it was all Gilbert could do to keep ahead.

In spite of all his care Gilbert hit a rock and his machine jumped into the air landing half a dozen feet away and nearly flinging him out of his saddle. Somehow he regained his balance and sped on towards the gate. He had almost gained it when the end came. The back tyre blew up with a bang like a pistol shot, the bike skidded and Gilbert went sprawling on hands and knees.

All that saved him was the report which so startled Vindex that he paused for an instant, snorting in anger and terror. Before he could start again, Gilbert had regained his feet and was scudding for the gate now only 20 yards distant. He gained it, put both hands on the top, and vaulted over. A loud crash made him think that Vindex had charged the gate, but as he swung round he saw that this was not the case. The big beast, baulked of his human prey, had turned on the bicycle, and charged it with such fury that his horns had got wedged in the spokes. This annoyed him intensely, and the crash which Gilbert had heard was caused by his ramming the battered machine furiously against the wall in the effort to get rid of it.

The result was startling. The poor old bike went all to bits, and most of it fell in ruins at the foot of the wall; but the front wheel remained fixed on Vindex's horns, and off he started, galloping madly in a wide circle, tossing his head and bellowing frantically. Dismayed as he was at the loss of his machine, the sight was too much for Gilbert, who burst out laughing.

The front wheel remained fixed on Vindex's horns.

And just then Paul arrived on the scene.

"What are you doing here, you? What are you doing to my bull?" He was purple and hoarse with fury, and looked really dangerous. Gilbert swung on him.

"It would be more to the point to ask what your bull's doing with my bicycle. This is going to cost you the price of a new one." Gilbert's cool reply was like oil on the fire of Shelcott's fury. It made him so angry that for a moment he merely spluttered.

"Curse your cheek!" he got out at last. "You come trespassing on my land, abusing my animals. I'll have you in gaol for this!" Gilbert shrugged.

"Try it, Shelcott! Telephone for the police, and see which of us goes to gaol. I can tell you it's a pretty serious offence to leave a dangerous bull in a field through which there is a footpath. And I'll tell you something else—if I hadn't happened along when I did you'd be up at the next Exeter Assizes for manslaughter. That beast of yours was chasing that girl over at the far gate, and would most certainly have killed her if I had not interfered." Gilbert spoke with a cool certainty which impressed Shelcott in spite of his rage.

"The path isn't public," he snarled at last.

Gilbert's lip curled. "That's a lie—and you know it. This is going to cost you thirty pounds, Shelcott; and if I don't get a cheque to-morrow you'll get a lawyer's letter. I have a witness, and I'll go and make sure of her before you get at her."

He swung on his heel and walked away round the field, leaving Shelcott fairly flabbergasted. It was years since anyone had dared to speak to him in such a tone, and that his despised ex- clerk should do so made him feel as if he had been bitten by a rabbit.

Nance had come hurrying towards Gilbert, and the two met half- way. Gilbert, whose only idea had been to find a witness on his side, got a distinct shock when he came face to face with the prettiest girl he had ever seen—not even excepting Ida Merrill. And not only pretty, but with that indefinable stamp of breeding which so far Gilbert had hardly ever encountered.

"It was splendid!" she said, and her blue eyes shone. "Do you know, I—I really believe you saved my life." Gilbert felt suddenly bashful.

"It—it was the only thing I could do," he stammered.

"Save my life, you mean?" asked Nance demurely; and then they both laughed and the tension was snapped.

"You know I didn't mean it that way," said Gilbert. "I meant I had to draw the old beggar off."

"You did it wonderfully well," declared Nance. "But I had a bad moment when that tyre of yours blew up. I quite thought the nasty beast had got you."

"He only got the bike," said Gilbert.

"But he's smashed it all to bits," said Nance, suddenly grave. "You must let me make the damage good, Mr.—"

"Stratton is my name," put in Gilbert quickly, "but please don't speak of such a thing. It's all the fault of Shelcott, owner of the pit. He had no business to leave the bull in the newtake."

"Is he the man you ware talking to?"

"Yes. I used to work for him." Gilbert's voice was suddenly grim, and Nance gave him a quick glance.

"You don't like him," she said.

"We're not exactly bosom friends," remarked Gilbert. "I shall enjoy making him pay for a new bicycle."

"Well, I'll be your witness if he makes any trouble," vowed Nance. "My name is Nancy Aspland, and I live at Brimmacombe."

"I know—The Roost," said Gilbert quickly. "But what brings you up here on top of the moor?"

Nance explained about Mrs. Betts, and Gilbert nodded.

"I know her quite well. Widow of a poor fellow who was killed by an accident in the pit. A very nice woman, too. I'm going up to see my old foster-mother, Mrs. Clamp, so we may as well walk together."

"That will be very nice," said Nance, "especially if there are any more bulls about." Before they reached the row of cottages they were talking like old friends. Gilbert took her to the door of Betts' little house, and there she turned: "But how are you getting back?" she asked.

"Shank's mare," smiled Gilbert. "Perhaps you'll let me walk with you. Our roads lie together as far as Monk's Cross."

"That will be splendid." declared Nance.

"Splendid," agreed Gilbert happily. "I'll come back here for you in about half an hour." He went on to Clamp's. Mrs. Clamp was delighted to see him, and still more delighted when he told her of his new job. Her worn face shone.

"Five pounds a week! Why, you'm rich, Mr. Gilbert."

"I'll be richer still when I've collected that thirty pounds from Paul Shelcott," said Gilbert; but the good woman shook her head.

"You be careful. Mr. Gilbert. He'm a bad man, and I tell 'ee, he won't stop at much to get even with 'ee."

"He can't hurt me," said Gilbert confidently, and went on to make arrangements for having his goods hauled over to Elford that evening. Clamp would do it after supper. Then he went back cheerfully to meet Nancy, and found her equally cheerful, for Mrs. Betts had promised to come back to The Roost, so her domestic difficulties were solved.

The two walked off together across the moor, chatting as they went. Nance told something of her life in London, and was amazed to hear that Gilbert had never been there.

"But you seem to know so much about it," she said in a puzzled tone.

"I read," replied Gilbert modestly. "There isn't much else to do on winter evenings."

"I think it's wonderful," said Nance, and Gilbert glowed inwardly. The two were so interested in one another that they never saw or heard a man who rode up behind them.

"Hulloa, Stratton," he called, and Gilbert looked up to see James Merrill on his smart cob.

"Good morning, Merrill," he said brightly. "May I introduce you to Miss Aspland?" Merrill took off his hat with a flourish. Nance nodded.

"I hear you're staying with Barr," said James.

"Yes, but only until to-night. I've a job, Merrill."

"Have you, by Jove?"

"Yes, up at Elford."

"What—with Cowling?"

"Yes, I go there to-night."

"Congratulations! You won't forget Sunday."

"Not I," said Gilbert; and Merrill, raising his hat again with a smile, trotted off.

But he was not smiling when he reached home. On the contrary, there was a heavy frown on his face as he went into the house to look for his sister, whom he found arranging flowers in the dining-room. She looked up.

"What's the matter, James?" she asked lazily. "You look like a thundercloud."

"I've just seen young Stratton," he said. "He's got a job and a girl." Her lips tightened.

"Will you kindly tell me what you mean, James?"

"Exactly what I say. Gilbert Stratton was walking with a girl—a very pretty girl, and one years younger than you. This has got to be stopped, and it's up to you to stop it." He paused. "We're pretty near the end of our tether," he added significantly.

IDA'S whole face hardened. All its charm was gone, and she looked her full thirty years, or even more.

"What do you mean, James?" she asked, and her voice was as sharp as her looks.

"Just exactly what I say, my dear Ida. I've overdrawn at the bank; bills pile in every day, and if something isn't done we'll have to pack up and clear in a hurry."

"Clear—where to?"

"I shall go to America. You—well, I should suggest that you might find an opening in some seaside hotel where good- looking barmaids are still in request."

"You're a beast, James. You always were a beast."

He shrugged his shoulders.

"Abuse won't get you anywhere. The remedy is in your own hands. You have only to catch this boy, and we're in easy street for the rest of our lives." Ida's face was furious with scorn.

"So you think you'll share Messenger's millions?" she sneered.

"I'm quite sure I shall," replied James, calmly. Defiance shone in Ida's eyes.

"Suppose I turn the whole thing down. Paul Shelcott would marry me any day."

"You'll never marry Paul Shelcott," James stated.

"You mean, you'd tell him?"

"Exactly. I don't want my half-sister prosecuted for bigamy."

"It will be bigamy just the same if I marry young Stratton," cried Ida.

"Speak a little more quietly, my dear," advised James. "Maids have long ears. Yes, of course it will be bigamy in any case, if you marry again while your present husband is still alive; but if it's Stratton, that doesn't matter, for a small allowance paid quarterly will keep Master Purvis's mouth shut."

"I think you're a devil, James," said Ida very slowly and distinctly.

"Not a devil or an angel—merely a man," replied James. "Now let's have an end of these heroics. Stratton is coming again on Sunday, and it's a pity if you, with all your cleverness, can't catch a raw boy like that."

He turned and left the room, and Ida dropped upon a chair and sat biting her lip, trying hard to compose herself. She was old enough to know that scenes like this played the very devil with her looks. She wasn't left long in peace, for within three minutes James was back in the room with a newspaper in his hand, and a look of unusual excitement on his face.

"Here's a nice business," he said sharply. "Old Messenger is missing." He held the paper out to her, pointing to a headline.

"A Missing Millionaire." Ida took the paper and glanced quickly down the column. Presently she looked up.

"They seem to think he's dead," she said slowly.

"And the odds are they're right," responded James. "When a man of that age stays away from his home you may take it as certain that something has happened to him. He has either drowned himself or some one has knocked him on the head."

"Then—then—" said Ida, "it's too late."

"Too late—what do you mean?"

"They will find Gilbert Stratton and tell him that he is the heir." James gave a short laugh.

"Anyone would think you were thirteen instead of thirty," he sneered. "Haven't I told you a dozen times that you and I are the only people who know that Gilbert Stratton is old Messenger's nearest relative? The lawyers—everyone believes that fat fellow, Aspland, is the heir, but he's only a great-nephew," he added, "and Stratton is grandson. Stratton's mother was Messenger's own daughter." Ida thought a little.

"But won't Aspland claim the money?" she said at length.

"Probably he will, but he can't touch it till there's proof of the old man's death." He paused. "All the same, it doesn't leave us much time, and the sooner you get to work the better. You want to have him tight before a word gets out," he added cynically. Ida shuddered.

"A raw boy like that," she muttered.

"Better than an old lag," retorted James brutally. "And once you've landed him you needn't have any more to do with him than you like." He stood looking down at her with hard eyes.

"All right. I'll do it," she said, and with a laugh James again left the room.

Gilbert, meanwhile, had started work at Elford. He was a little nervous at first, but soon found that, though there was plenty to do, there was nothing beyond his powers. His new employer was amazingly competent, and worked, himself, a full eight-hour day. He lived in a small house close to the office where the wife of one of the quarry-men did his cooking. Each morning he had Gilbert into his office and gave him dry, precise directions as to what was to be done, directions which Gilbert had no difficulty in carrying out. Gilbert had the happy knack of getting on with the workmen, and before the week was out had come to know most of them.

Sharp at twelve on Saturday work ceased for the week, but Gilbert was so accustomed to carrying on that he automatically went back to the office after his midday meal. A few minutes later Mr. Cowling entered.

"Have you not finished your week's work?" he asked drily.

"I've pretty well cleaned up, sir," replied Gilbert.

"Then kindly leave the office, and go and take some exercise or amuse yourself. I do not care to have my employees damaging their health by working overtime, unless there is special need."

"Very good, sir," said Gilbert quietly, and retired. His spirits rose. He had money in his pocket, and the afternoon was fine. He made up his mind that he would walk into Taverton and see if the new bicycle he had ordered was ready. Shelcott had paid up all right.

To his delight he found the machine waiting for him, and he tried it out with great joy. It was a joyful contrast to the old rattle-trap which Vindex had destroyed. Then he went to the tailor from whom he had ordered his new suit on the previous Thursday. He had begged the man to try and get it finished by Saturday, but had hardly expected him to do so.

Here was another pleasant surprise. It was ready and it fitted well. Gilbert had it packed, he paid for it, then made a round of the shops and bought new shirts, socks, and ties. He even indulged in a new hat. After that he fell in with Tom Horner, who asked him to tea, and was anxious to hear about his work at Elford. Gilbert assured him that he got on capitally with Cowling.

"He's a queer old bird," he said. "Do you know anything about him, Mr. Horner?"

"Not much," admitted Horner. "When he opened his account with us he transferred from a Cornish bank, so he must have been in tin or clay down there."

"He knows granite," said Gilbert. "He'll make Elford quarry pay better than it's ever paid yet."

"So much the better for you, my son," smiled Horner; and then Gilbert said good-bye and went off with all the goods strapped on the carrier of his new machine, making him look as if he was a traveller in the drapery business. He had had a very good afternoon, and he spent a pleasant evening sorting out his purchases and putting his rooms to rights. It was jolly to have two rooms of his own after his one little bedroom at Clamp's, and he was very busy fixing up his sitting room. He wanted it to be fit to receive visitors.

Next day was fine again, and he shaved and dressed with unusual care.

The quarry woman who acted as his housekeeper smiled at him when she had laid his breakfast. "You'm proper smart this morning, Mr. Stratton," she said. "Looks like you be going coorting." Gilbert, to his disgust, got very red, which tickled the good woman immensely.

A little after twelve, he went off on his new machine, and as he ran easily down the long winding road he could not help thinking how much had happened in the one week. More than in any year of his life previously. He had met the Merrills, quarrelled with Shelcott, stayed with Bobby, got a new job, and—he felt an odd thrill as he remembered—made friends with Nance Aspland. He found himself wishing that he was going to lunch with Nance instead of Ida, and suddenly he was very cross with himself. "You're an ungrateful brute, Gilbert," he remarked emphatically, and, pushing over the lever, sent his machine whizzing down the slope.

The door of Woodend opened almost before his finger had left the bell push, and there was Ida, looking, so Gilbert thought perfectly lovely. She was indeed a handsome woman, but Gilbert, in his innocence was not to know how much her looks owed to art. She gave him both hands.

She gave him both hands.

"How smart you are, Gilbert!" she exclaimed. Then she looked a little confused, "Forgive me. I ought to have said 'Mr. Stratton.'"

"Please don't," begged Gilbert. "Gilbert sounds so nice from you." Her eyes widened a little. "He's not such a fool as he looks," was her thought, but what she said was:

"Then you'll have to call me Ida."

"I'll try," replied Gilbert, laughing. She took him round the garden, cut a late rose for his buttonhole, and they saw nothing of James until lunch-time.

Lunch was perfect as usual. There were partridges cooked as Gilbert had never seen them, a cream deliciously mixed with late autumn raspberries, and a savory of very delicate puff pastry just flavored with cheese. James sat and smoked a while with Gilbert, and talked of sport. It was one of the things James could talk about. Then he excused himself on the plea of having letters to write, and left Gilbert in the drawing-room with Ida. Ida made room for him on the sofa beside her. She laughed.

"It's absurd to think it's only a week since we first met," she said. "Tell me how you like your new work."

"I like it immensely," declared Gilbert. "Mr. Cowling gives me orders, but I have a free hand in carrying them out."

"Well," said Ida, "I'm glad you have found something not too far away. I was afraid, when you left the clay pits, that you might go out of this county altogether, and then we should have seen no more of you." Gilbert was flattered. What youngster of his age would not have been?

"Would you have minded?" he asked.

"Of course I should," said Ida softly. "Haven't I told you how lonely life is here on the moor?"

"But you and your brother must have plenty of friends."

"Acquaintances, yes, but friends are not so easy to find."

She looked up at him, and Gilbert saw that her eyes were not really green, but a curious hazel color, very soft and bright. They fascinated him, and all of a sudden he felt an intense desire to kiss her. And somehow he knew that she would not mind being kissed. He bent towards her.

Another instant and his lips would have been on hers, when all in a flash Nance's face rose between them. Nance, with her fresh, clear skin and bright, honest eyes. The illusion was so strong that Gilbert stiffened.

"I beg your pardon, Ida," he said gently.

"What for?" In spite of herself, Ida's voice was sharp. She had failed, and she had not the faintest notion why she had failed. She was furious.

JUST before dusk that afternoon Gilbert arrived at Bobby Barr's place at Randlestone, and Bobby welcomed him boisterously.

"Gosh, look at the man! I say, Gilbert, you didn't put on those togs to call on me." Gilbert tried to laugh, but made rather a poor job of it, and Bobby, who had a heap of good, sound common sense under his happy-go-lucky exterior, saw at once that something was wrong, and quickly changed the subject.

"I got another salmon yesterday, Gilbert. You must take a chunk of it home with you. But here's Mrs. Chard to say tea's ready. Come in and have a mug." He chattered away so cheerfully that Gilbert soon began to feel better. The tea was hot and strong, and there were Devonshire "tough cakes," light as feathers, with Devonshire cream and Devonshire strawberry jam. Bobby waited until he saw that his friend was in a better frame of mind, then began to angle artfully to get at the source of his depression.

"You been lunching with the Merrills, haven't you, old man?"

"Yes," said Gilbert rather shortly, and Bobby knew at once that he was on the track.

"Are you going there next Sunday?"

"No."

"Then come here. I want to fix up a picnic to Black Tor Gorge. You remember that girl you rescued from the bull, Miss Aspland?"

"Yes, of course."

"She and her father are coming. Is it a go?"