RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

Dust Jacket

"Martin Crusoe," C.A. Pearson Ltd., London, 1923

Book Cover

"Martin Crusoe," C.A. Pearson Ltd., London, 1923

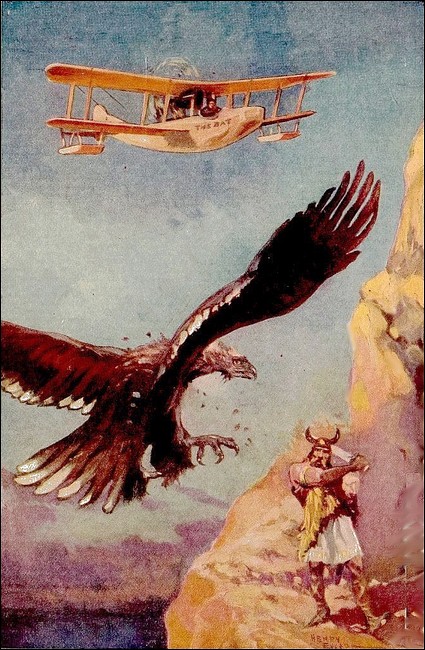

Frontispiece.

The Eagle's Attack.

WITH the telephones of his wireless fixed over his ears, a pencil in his hand, and a writing-pad before him, Martin Vaile sat listening to the signals that came through.

Some minutes passed, and Martin, tapping idly on the paper with his pencil, seemed little interested in the sounds. Then suddenly his attitude changed, his back straightened, and a look of eager interest lit his keen gray eyes.

His pencil began to work, and he rapidly jotted down a series of figures and letters on the paper.

Then he stopped writing and sat waiting, but nothing more came, and, glancing at his watch, he noted the time, slipped off the receiver, and ran his fingers through his close, curly hair.

The door of the big room opened, and a boy came quickly in, a boy about Martin's age, but as dark and slight as Martin was tall and fair.

"That you, Basil?" said Martin quickly. "I'm glad you've come."

Basil Loring gave the other a quick glance.

"What's the matter, old man?" he asked lightly. "Why this frown on your marble brow? What horrible news have you been absorbing out of space?"

"Nothing horrible, Basil, but something most unthinkably baffling. I've just had the sixth message from the unknown sender."

"The sixth message?" repeated Basil, looking puzzled. "What in the name of sense are you talking about?"

"Oh, I forgot. You've not been here for a week, and don't know anything about it. Well, every night for six nights past I have had a message from this unknown station. It gives the latitude and longitude, and says 'Help! Come to me!'"

"Sounds like an S.O.S., Martin. Is it a ship in trouble?"

"Bless you, no. Nothing of the sort. This is from a much more powerful installation than any ship has. Besides, it isn't a ship. The tuning is different."

"That's Greek to me," said Basil. "Explain."

"Well, you know we use different length waves for wireless work, and ships use comparatively short waves. By adjusting my apparatus, I can cut those out completely, so that all I catch is from the giant land stations such as the Eiffel Tower or Washington. Their wavelengths are much greater, and cannot be heard with the ordinary adjustment. The other night, as an experiment, I tried an even wider adjustment, and then came this mysterious message, or, rather, the duplicate of it; and each night since, just at the same hour, it has come again. As I told you, this is the sixth."

Basil stared. "I understand about the waves," he said. "But surely, Martin, if this is a big station that you are hearing from, it's easy enough to find where it is! All the big stations are known, aren't they?"

"This one isn't," Martin answered. "I can tell you this much: if the sender states his position correctly, it's right in the middle of the sea."

This time Basil was startled.

"If that's the case, it must be from a ship. And yet you say that it's from a big installation."

Suddenly his face cleared. "Tell you what, Martin, it's someone having a joke with you—some fellow in one of the other big stations playing a game."

Martin shook his head decidedly.

"It's not that, Basil. The message does come from the spot it is supposed to come from, or from that neighborhood. You see, nowadays, we are able to tell pretty accurately the direction of wireless signals. I have made experiments during the past week, and, as far as I can gather, the station is exactly where the sender says it is."

"Then there must be an island there," said Basil.

"If there is, it is not on my map, and, mind you, I have looked up the best government charts."

Basil shook his head helplessly.

"It's beyond me, Martin," he said. "Show me the spot on the map."

Martin took a chart out of a drawer and unrolled it. It represented that vast tract of the North Atlantic Ocean between the Canary Islands and the Bermudas, between twenty and thirty degrees north. Near the center of this, but a little to the west, Martin had made a tiny cross in pencil.

"There's the spot," he said.

Basil looked at it for some moments. "Why," he said slowly, "that's in the Sargasso Sea."

Martin nodded.

"Exactly. It is right in the center of that tremendous plain of weed which is drifted by circling currents into that dead water, and covers more than a million square miles. That is where the mysterious island must be, and that is the spot from which these queerly-tuned messages must be reaching me."

Basil stared first at the map and then at Martin.

"If the island is not charted, the only reason can be that the weed has prevented ships from getting to it," he said. "And if ships can't get to it, how in the name of sense has this fellow got there? And if he has got there, how did he ever get his wireless there, or put it up?"

"Just the questions I have been asking myself, Basil, and just the questions I mean to solve before I am very much older. I hope to be on that island within a month."

"You're going there?" cried Basil. "But how? Of course, you have the yacht, but she can't travel through the weed any more than any other ship."

"True, my boy. But if one can't travel through the weed the other way is to travel over it."

Basil's eyes shone.

"A 'plane!" he said breathlessly.

"I shall take the Bat, Basil. She will do the trick if anything will. A flying boat ought to be the very thing for the Sargasso."

Basil drew a long breath.

"Bully!" he said. "Oh, Martin, I wish I could come with you!"

"I wish you could, Basil," replied Martin gravely; "but I'm afraid it's out of the question. You've got to go back for your last term at 'prep.' school. In any case, your father would not hear of it."

"What about yours?" questioned Basil, quickly.

"I am wiring him tomorrow," Martin answered.

Twenty-four hours later Martin stood on the wide-stretching lawn. The stately house lay behind him; in front the Atlantic sparkled under the spring sun, and in the cove below lay the Flying Fox, a magnificent ocean-going craft of twelve hundred tons, in which Martin and his father had traveled thousands of miles across the seas of all the world. Martin's father was a very rich man, whose business interests lay in many countries.

The boy's eyes were on the drive. He was expecting the telegraph boy, with the answer to the message he had sent the previous day to his father, who was in Florida attending to one of the great land settlement projects he and his partner, Morton Willard, had started there.

A boy on a bicycle came up the distant drive, and Martin walked quickly down the slope to meet him.

"Telegram for you, sir," said the lad.

"Thanks," answered Martin with a smile.

"Dad is prompt," he said. "I hardly hoped to hear today."

He tore the envelope open, unfolded the flimsy sheet, and read the message.

The color faded from his face; his eyes went blank; he staggered and fell on the grassy bank. The slip fell from his shaking fingers.

Then, with a big effort, he pulled himself together, and, picking up the telegram, forced himself to read it again. This was the message:

DEEPLY REGRET TO INFORM YOU YOUR FATHER DIED SUDDENLY TODAY RESULT OF HEART FAILURE. AM MAKING ALL ARRANGEMENTS FOR FUNERAL AND WRITING BY THIS MAIL. WILLARD, SEMINOLE HOTEL, LACOOCHEE, FLORIDA.

"Dead! My father dead!" groaned poor Martin.

The shock was terrible, for Martin's mother had died when he was only a baby, and he and his father had been the greatest chums imaginable.

And now his father had died, hundreds of miles from home, without a last word!

For many minutes Martin sat there, staring blankly in front of him, but with his mind's eyes fixed on his father's face as he had last seen him, barely a month before. When at last he rose and went to the house he looked five years older than when he had left it.

How the next days passed Martin hardly knew. Everyone was as kind as could be, but he was in a dazed state and hardly knew what was happening around him.

What roused him at last was a visit from the family lawyer, Mr. Vincent Meldrum. He arrived with a bag full of papers and a very grave face. They met in the library, an oak-paneled room full of Mr. Harrington Vaile's books.

"Martin," began Mr. Meldrum, "I am going to tell you at once that I have bad news for you."

"It can't be any worse than I have had already," said poor Martin. "You needn't be afraid to tell me."

The lawyer looked at Martin and sighed.

"Martin," he said, "I have known you from a child, and I believe you have plenty of pluck. You will need it all, I fear. Having said that, I will not keep you in suspense. The big land scheme at Cleansand Bay has come to utter smash and the papers are saying it was a swindle from the beginning."

Martin leaped to his feet.

"A swindle! Who accuses my father of having anything to do with a swindle?"

"Steady, Martin—steady!" begged the lawyer. "You and I know better, but others do not. I fear there is no doubt about the swindle; but your father did not know this. He took Mr. Willard's word that the scheme was sound. Willard ran the whole thing, and, as you will remember, kept your father away from Florida on one excuse or another until quite lately."

Again Martin sprang to his feet.

"Then he murdered my father!" he cried fiercely.

Mr. Meldrum raised his hand.

"You must not make rash accusations, Martin," he said gravely. "There is no suspicion, let alone proof, that Mr. Willard did anything of the kind: in any case your father's heart was said to be weak."

"Then it was the shock that killed him," declared Martin; "the shock of finding that he was mixed up in a swindle."

"That is possible," replied the lawyer. "Now listen, Martin. This is a bad business. The loss to the investors runs into an enormous sum. I fear that all your father's property will be seized to pay the debt. There is this much comfort. The courts cannot touch the money you have under your mother's will, so you will have a small but sufficient income to—"

Martin broke in with a quick question.

"Is my father's money enough to satisfy the creditors?"

"I doubt it, Martin."

"Then you will take every penny, Mr. Meldrum—every penny, do you hear? Sell the house, the yacht—everything. Do you think I would let anyone say that my dad had swindled them?"

"YOU'RE going to the island, Martin?"

"I'm going, Basil."

"But—but what does old Meldrum say?"

"He doesn't know, Basil. He thinks I am going to Florida. So I am, for the matter of that, but I mean to visit the island first. You see, it all fits in perfectly. The people who have bought the Flying Fox want her delivered at Havana. So I may just as well go in her as not. And the Bat is my own. I paid for her out of my own allowance, and I feel justified in keeping her. I have told Captain Anson, of the Flying Fox, just what I want to do, and he has agreed. You are the only other person who knows about it."

Basil looked worried.

"I almost wish you hadn't told me. Suppose you come to grief?"

"If I do there's no one to miss me except you, old friend," said Martin, gently. "But don't be upset. There's no reason why I should come to harm. The island is not more than two hundred and fifty miles from the edge of the weed, and the Bat will cover that distance in two hours."

"Yes; but suppose you get there and can't get away again?"

"I don't see how that can be, unless I smash up the Bat, and if I do there's always the wireless with which I can call for help."

"I'd forgotten the wireless," said Basil. "Yes, you can do that."

He paused.

"But I say, Martin," he went on, rather doubtfully. "I thought your idea was to get square with Willard!"

Martin's face hardened.

"That is exactly what I do mean to do," he said sternly. "I shall never rest until he is punished—until all those poor people who have lost their money through him have been repaid to the last penny. But don't you see that this delay may help? At present Willard is on his guard. He will be looking out for me, and is sure to know that I am starting for Florida. If I disappear on the way he will think the danger is over. He won't worry. Then, when he has forgotten, I shall swoop down on him."

Martin's eyes were shining. Basil stared at him in wonder.

"You'll get him all right, I feel sure of that," he declared. "Besides, I daresay you'll make a fortune on the island. A man who has a great wireless like that must be awfully rich."

"I had thought of that," said Martin. "And I shall want money to tackle this swindler Willard. The messages make it quite plain that someone is wanted there, on the island, and if whoever is there will pay for my help, why, I sha'n't refuse the money. And now, good-by, Basil. Keep a still tongue, and I will promise you shall hear from me as soon as possible."

"Good-by, Martin!" said Basil, in a voice not very steady. "And just remember, if you are in a hole, I'll do anything on earth that I can!"

"I know you will," Martin answered, as he wrung his friend's hand. "Good-by again. I go aboard to-night, and we sail first thing in the morning."

Basil left, and Martin finished his packing. Two hours later he went aboard the yacht. At five next morning he was on deck. He stood alone in the stern, taking his last look at the beautiful old house with its wide, smooth lawns, and the tall trees behind with the rooks cawing in the branches.

The yacht swung southward around a tall headland, cutting off the view.

The Flying Fox traveling at a steady seventeen knots ran rapidly into the tropics and a week later lay rolling idly on the silken swells of mid-Atlantic. It was a heavenly day, the warm air soaked with sun.

To the north the sea lay open to the farthest horizon, but the view to the south was bounded by a dark line which at first sight resembled a low-lying shoal, but which was actually the edge of the monstrous mass of weed covering the Sargasso Sea.

Alongside the yacht, attached to a long spar which projected well beyond her side, lay Martin Vaile's big flying boat, the Bat, and on the deck of the ship Martin himself, in the thick overalls of a pilot, stood exchanging a last few words with bluff old Captain Anson.

"This is for Mr. Meldrum, captain," said Martin, handing him a letter. "But mind, I don't want him to have it until you get home again. Long before then you will have heard from me."

"I hope so, I'm sure, Martin," replied the captain, who was frowning uncomfortably.

"Oh, you'll hear all right," declared Martin with a smile. "I have told you there is wireless on the island."

"Ay, if there is an island at all," grumbled the skipper.

"There must be an island, or there wouldn't be wireless," insisted Martin.

"And suppose there is an island?" burst out the captain. "And suppose you reach it, what are you going to do when you get there? How do you know this fellow that has sent the message will let you get away again? Suppose you tumble into trouble, how are we going to help you? Just remember this is as close as any ship can get to this unknown land. Let me tell you, Martin, if your good father was still alive he'd never have let you go off on a wild-goose chase like this."

"But he is not alive," said Martin, sadly. "And even if he were I don't think he would forbid me, captain. Remember this, my only objects in life are to clear his memory and to punish this man Willard. As I have told you already, I must have money for both these purposes. I firmly believe that what I am going to do will be my quickest and best way to make the necessary money. And, quite apart from all that, the man on the island wants help, and I feel that it's up to me to bring it. Now, don't try to discourage me," he went on quietly. "My mind is made up. Let me feel that I have your good wishes, captain. I'm sure I shall need them."

"Certainly you have them, my lad," said the captain warmly, "and the good wishes of all aboard. Well, I'll say no more, except to wish you the best of luck. I hope you'll come out of it safely, with all the cash you want, and I for one will be uncommon glad to see you safe back again."

The two shook hands, then Martin went over the side and took his seat in the slim hull of the flying boat. The men above cast off, Martin pressed the button of the self-starter, the engines roared, and the Bat shot away from the side of the yacht. Sweeping up the side of one of the long, slow swells, she reached the smooth top, and, taking off like a sea-bird, rose bodily into the air.

Martin kept driving up and up, and as the needle of his barograph sank so did the mercury in the tube of the thermometer beside it. Above the instruments was his chart with the mark showing the exact position of the unknown island. He steered by compass, and kept the bows of his machine pointed almost precisely south.

Martin was a skilled pilot. He had been mad on aircraft even before he first went to school; and his father, realizing this, had started his training when he was only ten years old. His wealth had made it easy for him to give the boy the best teachers, and at seventeen. Martin was not only a first-class pilot and a certificated wireless operator, but he had a wider knowledge of general science, of electricity and of chemistry, than most men of double his age.

Having made sure that all was running right, Martin settled himself comfortably in his seat. Once in the air, a 'plane is far easier to handle than a motor-car. He was able to take it easy and to look about him.

Glancing downwards, he saw that he was already far from the open sea. Beneath him spread the brown mat of weed, stretching mile after mile in tangled masses.

Yet it was not all weed, for it was broken by lagoons of blue water. And, even at the height at which he sailed, he could see that these lagoons were full of life; the tropic sea seemed clear as blue glass, and he could see, far down in the depths, strange forms gliding at great speed. Once he noticed a huge whale, looking as if carved out of black rubber, in the act of broaching. In another pool he caught a glimpse of a monstrous tangle of twisted antennae, which he realized, with a shudder, must be one of the tremendous cuttles which are known to infest the tideless depths of the Sargasso.

Then he saw a ship. A sailing ship of large size she must have been, but her masts had gone overboard, leaving only the stumps; the cordage had rotted away, and she lay mouldering, lifeless, waiting until slow decay should cause her to sink into the hidden depths under the tangle which surrounded her.

He looked back. Very far to the north lay the blue line of open sea, and a tiny trail of smoke told where the Flying Fox steamed onwards to her destination. Martin shivered. After all, he was only seventeen, and he felt terribly alone.

This feeling soon passed. The interest of the scene enthralled him. For now he saw more ships, and he noticed that, the farther he got into the heart of the ocean jungle, the more ancient the type of vessel that lay within its festering tangles. Here was a galleon with a high poop-castle and quaintly curved bow, and a mile away a strange-looking ship which was like a picture he had seen of the Great Harry, a famous war vessel of the sixteenth century. It seemed clear that either the weed area had been steadily increasing during the centuries or that some hidden current sucked the trapped ships deeper and deeper into the heart of the weed sea.

An hour had passed. It had seemed like five minutes. But he did not yet begin to strain his eyes for sight of the island, for he knew that he had still fully two hundred miles to go. And even the towering peak of Teneriffe is not visible more than a hundred miles out to sea.

Now he passed across a wide belt of open water which fairly teemed with marine life. Here was a school of cachalots, led by an old bull that must, Martin thought, be over a hundred feet in length. It came to him that this was where the whales had sought refuge from man's age-long persecution.

Another hour. Still the breeze held, still the sky was unsullied by a single cloud, and still his engines thundered in perfect rhythm.

Martin began to glance ahead. His heart was beating rapidly. At any minute he might sight the goal of his adventurous journey.

What was that? Was it a white cloud, or was it the gleam of a snow-capped peak hung high against the southern sky? Five minutes more, and Martin, half choked with excitement, knew that it was indeed a mountain. The island was no dream.

FIFTY minutes later, and the Bat was shooting like a meteor towards a vast dark mass of land surrounded by a wide belt of shining sea. Martin was near enough to see plainly the enormous cliffs and frowning precipices which bounded it.

The island was about twenty miles long and nearly as wide. In the centre rose a mountain with twin peaks white with snow, and from one of which a thin coil of smoke drifting lazily across the blue proclaimed it to be a volcano not yet extinct.

Here and there were patches of vivid green, but whether forest or bush, or merely grassland he was not yet near enough to see. To the west, so far away as to be merely a blur on the horizon, was what appeared to be another island.

As Martin drew nearer he was more and more impressed by the savage grandeur of the scenery. This was no coral island, but a great volcanic mass, clearly a survival of some continent long since whelmed in the depths of the sea.

He stared hard, but could see no sign of life upon the land. The only smoke was the faint curl from the tall peak. There was no sign of house or building nor, as far as he could see, of any cultivated land.

The next thing that struck him—and struck him very unpleasantly—was that there did not seem to be any place to make a landing. There was the sea, of course, but if he alighted on the sea he was faced with those enormous cliffs, up which there appeared to be no way of climbing. There was not a yard of beach anywhere. Even the deepest inlets seemed to be mere fiords faced with grim precipices.

Rising again, he circled higher, the roar of his engine coming back in rattling echoes from the wilderness of crags below. The higher he rose the less he liked the look of things. It seemed certain that he must either land upon the sea, or else turn and fly back to where he had come from.

Martin was one of those lucky people whose brains always work most quickly in an emergency, and like a flash it came to him that, even if he could not see the nameless inhabitant of this mysterious island, it was probable that the other was aware of his approach. He remembered his wireless.

While it is still rare for any 'plane to carry a wireless sending installation, all the larger types of aircraft are fitted with receiving apparatus. It was the work of a moment to clap the telephones to ears and release the wire.

Instantly came the whistling notes in sequence, and presently he was reading out a message repeated time and time again:

"Pass twin peak to north. Land on lake beyond!"

Instantly obeying the order, he opened his throttle to its widest and went rushing round the shoulder of the northern peak. He gave it a wide berth. As it was, the hot air from below, mingling with the cold breath from the snow-capped heights, made wild eddies which swung his big 'plane giddily. But the giant power of his engines carried him safely through this peril and, sure enough, beyond and beneath lay the lake that the message had told of.

It was a mountain tarn, perhaps three miles long and a mile wide, and rimmed with precipices looking every bit as savage and inaccessible as the sea-cliffs themselves.

Yet Martin did not hesitate. He had every confidence in the mysterious guidance which had brought him so far, and, besides, he had no choice in the matter. Cutting out his engines, he glided down in a long, silent volplane, to land, light as a homing sea-bird, upon the dark surface of the lonely lake.

He had now been flying for more than four hours, and it was a relief to his tired nerves to release the controls and lie back a moment and look around him. The lake, as he had observed already, was long and narrow. It was evidently of enormous depth, and, from the black basalt cliffs which bordered it, he gathered that its bed must be the crater of an old fissure eruption.

Martin was not left long to consider his surroundings. All of a sudden the quick beat of a motor engine reached his ears, and, looking behind him, he saw a small launch shooting towards him at great speed. Where it came from he had not the slightest idea, for so far he had seen no possible landing-place. Yet there it was, and in the stern sat a man who steered his smart craft straight towards the flying boat.

Martin's heart throbbed with excitement. Here was the stranger who had called to him across all those thousands of miles of ocean.

Soon the launch was near enough for Martin to see the face and figure of the solitary steersman. The first thing of which Martin was conscious was that the stranger was a man of great height and magnificent physique, the second that he was old beyond belief.

His hair, still thick, was white as the ice-cap of the peak above, and so were his beard and mustache. The skin of his face was brown as parchment and seamed with a million wrinkles, and his cheekbones stood out prominent like those of a mummy. Yet his eyes were dark and piercing and there was still an air of power and strength about him, which was intensely impressive. Martin stared at him as though fascinated. He felt himself in the presence of an unusual personality.

The launch came alongside, and Martin found himself waiting breathlessly for the other to speak.

He had not long to wait. The white-haired giant raised his soft hat courteously.

"Welcome to Lost Island," he said in a deep voice. "My name is Julius Distin, and I wish to assure you that I am very grateful to you for coming to my help."

"I am Martin Vaile," Martin answered simply. "I consider myself very lucky to have been the one to pick up your message."

Julius Distin looked at Martin thoughtfully.

"You took it yourself?" he questioned quietly.

"Yes," replied Martin. "I was trying some extra wavelengths, and I just chanced on your signals."

Distin nodded. "The true spirit," he said. "You are young to have it. You are young, too, to have made such a flight unaided. So that is an aeroplane? I have never seen one."

Martin gasped. He could not say a word. The idea that this wonderful old man had never so much as set eyes upon an aeroplane struck him as the most amazing thing he had ever heard.

Distin smiled. "Yes, I have no doubt you are surprised. But it is nineteen years since I last visited the outer world. Still, the shape is familiar to me. I know of all the latest experiments, from the Wrights onwards."

"By your wireless, sir?"

"No, I have books."

Again Martin could only stare, and again the old man smiled. It was a pleasing smile, Martin thought.

"Wait a while," went on Distin. "I will tell you all about these things a little later on. But first we must get in. We have sharp storms here sometimes, and it would never do to risk this beautiful machine of yours. Give me your tow-rope."

"I can taxi in," said Martin.

"No, you must not waste your gasoline. I can tow you easily."

He took the rope, made it fast, restarted his engine, and turned back. As they neared the cliff on the north side of the lake, Martin saw a great rift open, a sort of fiord only a few yards wide, but very deep. The towering cliffs nearly met overhead. They passed straight down it, and as they went it grew narrower, until at last they were moving in deep gloom under an arch of rock resembling the aisle of a giant cathedral.

Distin stopped the launch.

"Here we are," he said; and Martin realized that they were floating in deep water at the foot of a low quay of rock. The old man rose to his feet and stepped out. There was the click of a switch, and Martin blinked in the dazzle of huge arc-lamps which shed a glare of white light over a monstrous staircase hewn in the living rock and stretching away up into the heart of the mountain.

Before Martin could recover from his astonishment, Distin stepped to one side and pulled over a lever. There came a sound like the fireproof curtain dropping in a theatre, and Martin saw a real curtain of metal bars descending behind them from the roof of the cave. It dropped to the water and below it.

Martin turned amazed eyes upon his guide.

"W-hat—" he began.

"We have our enemies," said the old man, gravely. "It is as well to be on the safe side."

Martin stared at his companion.

"Then you are not alone on the island," he said quickly. "There are natives?"

Professor Distin smiled.

"I am quite alone except for my servant Scipio and yourself," he answered. "The enemies I speak of come from that other island which you must have seen from your plane."

"The one to the west?"

"Yes. It is called Lemuria; it is much larger than this, and has a good many people upon it."

"Who are they?" inquired Martin eagerly. "Caribs?"

"Oh, no! A much older race. To the best of my belief they are the survivors of the ancient Atlanteans, but they are not of pure blood. There is a Norse strain in them. I discovered this island from an old Norse chart."

"A Norse chart?" repeated Martin, in astonishment.

"Yes; but, Mr. Vaile, I must not keep you standing here. We have very much to talk over, you and I, and I am sure you are tired and hungry. Come with me, and over supper I will tell you my story and hear yours."

HE led the way up the broad stone stairs. As Martin followed he was struck by the magnificent proportions of the great flight of stone steps, and the splendid arch of the rock overhead. It was clear that the whole was the work of man's hands. As for its age, that was incalculable. The steps were worn smooth as glass by the passage of thousands upon thousands of bare feet.

The staircase swung in a grand curve, and, reaching the top, Martin suddenly found himself in a vast pillared hall, hewn, like the stairs, in the living rock, and flooded with electric light. The walls, the pillars, the roof itself, were covered with an intricate mass of carvings representing birds, beasts and reptiles, many of them unknown to Martin. And these all glowed in wonderful colors as brilliant, apparently, as the day they were laid on.

Martin was struck dumb. He could do nothing but stand stock still and stare around him.

"Very wonderful, is it not?" said the old Professor. "The people from the Smithsonian Museum would give something to see this. See, here is the ichthyosaurus, the great fish lizard, and here is a dinosaur. Up on the roof above us are a flight of pterodactyls, the terrible flying lizard of the ancient days. You will find here representations of most of those giant animals which we know only from the fossilized bones we dig up; and here is proof positive that man—highly civilized man—lived cheek by jowl with all these marvellous beasts of earth's earlier days."

"It is wonderful," said Martin, in a whisper, "almost too wonderful."

"I shall show you even more wonderful things than this tomorrow," replied the Professor, in his quiet way. "But we do not live among these monsters, I am glad to say. Follow me."

Passing through the vast pillared hall, he took Martin through a curtain doorway into another cave. This was a spacious rock chamber with great windows facing on the lake—windows which were set with panes of plate glass, through which the afternoon sun shone pleasantly.

Martin was getting used to marvels. Yet the contrast between this room and the sculptured extravagance of the pillared hall was as startling as anything he had yet seen. White matting covered the floor, and the walls were hung with soft draperies. Here were big cane chairs, photographs, pictures, English furniture and quantities of books.

On the far side was a door leading into a second room furnished as a bedroom, and beyond were still more rooms.

"This was a rock gallery," explained Professor Distin. "We partitioned it off into rooms. Yours is the third; and when you are ready, come back to the sitting-room for supper."

Martin found sweet-smelling soap, warm water and clean towels. It was like his bedroom at home. When he came back a table was set, and a man of color in neat drill was just bringing a hot dish.

"Mr. Vaile," said the Professor, "this is Scipio Mack, the one survivor of those who came with me to Lost Island."

Scipio laid down his dishes.

"I'se mighty glad to see you, Marse Vaile," he said, showing his white teeth in a cheery grin. "As I done told de marster, he and me was getting plumb tired of one anoder's company. We're right pleased to welcome you, sah."

"Thank you very much, Scipio," replied Martin cordially.

He liked the look of the man as much as the master, and for the first time since the sudden death of his father began to feel a little less lonely and unhappy.

He soon found that the negro was a wonderful cook. Supper began with excellent grilled fish. It was pompano, the Professor explained. With it was served cassava, sweet potatoes and maize bread. Then came a salad made of avocado pears, the most delicious thing of the kind that Martin had ever tasted. Dessert was stewed guavas, custard apples, huge Bahia oranges and luscious mangosteens. They finished up with a cup of fragrant black coffee.

The Professor watched Martin eat, and smiled at his good appetite.

"Yes," he said. "We grow all this fruit ourselves. You shall see our garden to-morrow. It is in a hollow on the mountain side. I can get oranges into full bearing in three years."

Martin stared.

"How on earth do you do that, sir?"

"Electricity," replied the Professor quietly. "I have made a study of electro-culture. Indeed, we do everything by electricity, including our cooking."

"Where do you get your power?"

"Water—a glacier stream, fed by the snows above. It works my wireless also."

"Then you have turbines," said Martin, as he sipped his coffee.

"Oh, yes! We brought those with us."

"But how?" began Martin, in fresh amazement.

"Quite simple, my boy. We came here in a submarine. There were two of us. Dr. Olaf Krieger, a Danish man of science, and myself were anxious to carry out certain experiments, and we wished to be quite undisturbed. Krieger it was who happened on the old Norse chart of which I have spoken. It seems clear that, in those days, the currents in the Atlantic were different, and that these islands were not so completely surrounded by weed as they are to- day. We resolved to come here. The question was how. Twenty years ago the submarine was still in its infancy; but I knew something of Mr. Holland's experiments, and we built a submersible craft of about five hundred tons, called the Saga, which proved to be very successful. We collected seven good men, and, diving under the weed, reached the island successfully."

He paused and a look of sadness clouded his fine old face.

"Of the original nine who set sail nineteen years ago, Scipio and myself are the only survivors."

Martin waited breathlessly. The Professor went on:

"Two of us, Norton and Philips, were killed when the Lemurians first attacked us. Then Krieger, with three men, went back for fresh men and machinery. He returned in safety with a cargo of necessaries and two new men. They were good fellows, and we lived here very happily together, busy all day and every day, and keeping in touch with the outer world by means of our wireless. It is true we were attacked more than once, but with modern devices were able to keep even the fierce Lemurians at bay. All went well until, in 1914, the great war broke out. We heard the news with horror, for we foresaw the terrible nature of the struggle."

"Doctor Krieger, believing that Denmark would be brought in, and aware that his scientific knowledge would be of great value to his country, decided to return and offer his services. He sailed, leaving Scipio, myself, and a man named Caunter in charge. With our electric devices we were safe from the Lemurians, and he promised to send the Saga back at once."

"Alas, he never reached Denmark! From that day to this I have never heard a word of him or of the Saga. There is no doubt that they struck a mine or got entangled in one of the great steel nets set to catch under-water craft."

The Professor sighed again heavily. "For a long time I waited, hoping against hope for news. When at last I realized that it was hopeless, I realized also that we were completely cut off unless I called outside help. This I hesitated to do, for I could not, of course, tell who would answer, and I was afraid of the Germans catching my messages. Then came a new disaster. Caunter, fishing on the lake, was attacked by some monster of the depths; and, before we could help him, the boat was smashed and he was dragged down."

"What sort of beast?" asked Martin breathlessly.

"A manta—one of the great rays. The lake, I may tell you, is salt, and communicates with the sea by a narrow, winding passage, and strange creatures come in at times from the outer ocean."

"And so," continued the Professor, "I waited only until I knew the Germans were beaten, then I began to send out my messages, timing them so that only some experimentalist like yourself would be likely to catch them. And so you have come, and once more I beg to tell you how grateful I am."

Martin grew red.

"I don't deserve your thanks, sir," he answered bluntly. "I came as much for my own sake as yours."

"It's this way," he went on. "I have lost my father and everything else through the villainy of his partner, a man called Morton Willard. I want money to clear my father's name."

"Tell me," said the Professor.

Martin explained. He told the whole story of the Cleansand Bay swindle, and of how Morton Willard, himself the real culprit, had thrown the blame on Mr. Vaile, and after his death cleared out with the spoil of which he had robbed the unfortunate settlers.

"So you see, sir," ended Martin, "my chief object in life is to make sufficient to pay off every claim against my dear father and clear his name. After that"—his face hardened as he spoke—"I propose to go after Willard."

Professor Distin nodded.

"Your feelings do you credit, my boy, and, as far as in me lies, I will help you. I am not a rich man, for I spent most of my capital on the Saga, and though there are valuable minerals on this island, there is no gold. Yet there is gold in plenty not far away. Lemuria is full of it."

Martin's eyes glowed.

"How do you know?" he asked.

"From the Lemurians who invaded us. Wait. I will show you."

He went across the room, and took down from the wall a heavy shield made of the hide of some unknown animal, and studded with great bosses of yellow metal.

"There is at least a couple of pounds' weight of gold on that alone," he said. "Their helmets, too, were covered with gold. It seems to be the only metal they have, except bronze. But they have pearls, too, for some of the men wore strings of them. The trouble will be, of course, to get hold of some of these valuables."

Martin's face fell.

"I had forgotten. No, of course we can't," he said dolefully.

"I am not so sure of that," answered the Professor. "I am as anxious as you to visit Lemuria, for there must be much there of immense interest. These Lemurians, remember, belong to a race long extinct on the rest of the planet. I have of late made a plan for getting into communication with them."

"My idea is," continued the Professor, "to capture some of them, and to teach them by kindness. Once we master their language I believe we might make friends."

"That is a splendid idea, sir!" cried Martin. "The one thing I don't see is how we are going to catch them."

"Wait till they visit us again. They come here about once a year. My own belief is that the painted cave is a sacred place to them, a sort of shrine of pilgrimage, and that they attack us simply because we keep them out of it." The two sat chatting together until past ten o'clock. Martin could have talked all night. He was too intensely interested to feel sleepy. It was the Professor who at last sent him off to bed.

The bed had a spring mattress and snowy sheets. Martin had hardly laid his head on the pillow before he was sound asleep. The next thing he knew someone was shaking him by the shoulder, and, opening his eyes drowsily, he saw the black face of Scipio bending over him. The man had a lighted candle in his hand.

"Yo' get up quick, Marse Vaile," he said, in a low voice. "Dar's trouble brewing."

"What's the matter?" inquired Martin sleepily.

"Dem fellers from de oder island. Dat's what de trouble is."

"An attack, you mean?"

"Dat's so, boss. I reckon dey seen yo' airyplane, an' dey come to find out what sort o' hoodoo yo' come to make. Dar dey are."

Martin sat up, broad awake now.

Through the breathless hush of the warm, dark night there came a strange low chanting, accompanied by the steady splash of oars.

"THERE ain't no need to break your neck a- hurrying, Marse Martin," suggested Scipio mildly. "Them folk ain't a-going to git through the water gate, not in any sort of quick time."

"There is no other way of getting in that I know of, Mr. Vaile," said Professor Distin, who had just come into the room.

"Please don't call me Mr. Vaile," broke in Martin quickly.

"Very well, Martin," answered the old gentleman, with a smile. "Now, if you are dressed, come with me. I will warrant you a sight such as few men have seen, something that will take you back a thousand years and more."

He led the way into the big living-room. Here all was dark, and Martin stumbled against a chair.

"No lights," explained the Professor. "It would not do. Although these windows are sixty feet above the lake, I would not give much for my glass if even a gleam of light were seen behind it."

"What—they haven't guns?"

"Hardly. They do not know what powder is. But they have slings and long bows. The slings are, no doubt, the old Atlantean weapons, and the bows they must have got from the Norsemen."

"Now follow me," he added. "Keep close, and do not on any account move away from me."

"But don't we want weapons?" asked Martin, in surprise.

"I have a pistol in my pocket, in case of emergency," replied the other. "But the last thing I wish to do is to kill, or even injure, any of these people. We never have done so unless absolutely driven to it."

"But you had a fight once. You told me you lost men."

"Morton and Philips," answered the Professor sadly. "The Lemurians got into the Painted Hall through a passage of which we did not know the existence. We had to kill seven of them in all."

"But here is a weapon, if you want one," continued the Professor, and he took down from the wall a great bronze battle- ax of which the handle was banded with gold. "We took that from one of the dead men."

Martin took it, and followed his guide out into the Painted Hall. Flashing his little light upon the bare rock floor, the Professor picked his way among the pillars to the head of the great stairway, but on reaching this he switched off the torch again, and took Martin by the hand.

"Not a sound," he whispered. "Not a sound now, if you value your life."

With the warning he led Martin down the broad, smooth steps. From below came a confused splashing and the booming sound of deep voices. A smoky glare of light was reflected upwards from the tunnel.

Half-way down the Professor drew Martin into a deep niche in the rock wall. There was the snap of a switch, and all of a sudden the whole scene leapt out under the glare of the powerful electrics. At the same moment a shower of arrows came whizzing through the air.

Martin drew a long breath. The Professor had promised that he should see a strange sight, but this—this was beyond anything he could have dreamed of. For there, in the black rock tunnel, just outside the steel bars of the water gate, lay a craft that brought back memory with a flash to the picture-books of his childhood. With its high-beaked prow and raised stern, the shields lining its bulwarks, and the long oars protruding from port-holes in the sides, it was a Norse long-ship, one of those wonderful open craft in which the Vikings crossed the whole width of the stormy Atlantic from Denmark to Greenland and Vineland.

If the craft was wonderful, her crew were more wonderful still. There were about thirty of them. Not one was less than six feet high or forty inches round the chest. Most had skins of a pale golden brown, but two or three were quite fair under their coat of sun tan, and had long, yellow hair. Their splendid appearance was made more splendid by their dress—a sort of close-fitting tunic reaching to the knees, and made of a white fabric blended with gold thread. They wore helmets ornamented with gold, and their shields, too, were studded with great golden bosses.

Sandals were on their feet, bound with leather thongs which criss-crossed their sinewy legs; and for weapons they had not only bows, but short swords and battle-axes, the blades of which were of bronze, heavy and sharp as tempered steel.

"Fine specimens, eh, Martin?" said the Professor in Martin's ear.

"Splendid," whispered Martin. "But surely the gate will never hold against them."

"They know too much to touch it," answered the Professor dryly. "I shouldn't like to say how many volts it is charged with."

"Then what are they doing there at all?" demanded Martin.

"That is what I am here to find out," replied the Professor. "They know as well as I that the gate forms an impassable barrier."

There was a pause, but behind a barricade of shields in the bow of the ship something was happening. Martin waited in breathless suspense. All of a sudden two splendid figures, stripped stark naked, dived like otters into the dark water.

"They're going to dive under the gate," Martin said in a whisper.

Nearly a minute passed while Martin watched breathlessly the space of water lying between the gate and the wharf where lay the launch. It was clear that the invaders were going down to a great depth so as to avoid the electric barrier.

The dark water broke, and the two heads appeared side by side. The white glare of the electrics showed up every feature plainly; and Martin saw no look of fear in the eyes of either of them. Treading water a minute, they looked all round, then both swam towards the launch and caught hold of the stem.

"They'll wreck her!" breathed Martin in alarm.

"I don't think so. Besides—." And Martin saw a smile on the wise old face beside him.

The two giants pulled themselves aboard the launch. They stepped gingerly, glancing around in evident discomfort. A boat with no oars or sails was something they could not comprehend.

The launch rocked a little under the weight of the two Lemurians, who must each have weighed at least fifteen stone, and every ounce of it solid bone and muscle.

Still the Professor did not move. Well hidden in the deep recess, he watched the curious scene beneath.

One of the Lemurians stooped and ventured to lift the hatch over the engine. As he did so, the Professor raised his hand and pulled over a switch. The result was almost as startling to Martin as to the Lemurians. A blast of trumpets sent the echoes crashing up and down the tunnel, and out into the rocky fiord beyond. The sound came from somewhere inside the launch. It was followed by a voice, a thundering voice which roared out something in a language which Martin could not understand, but which sounded like a very vigorous command.

If Martin did not understand it, the Lemurians did, or, at any rate, they seemed to. They leaped overboard and disappeared into the depths of the channel. A few moments later they bobbed up on the far side of the water-gate, and were hauled aboard the long- ship. The ship instantly cast off. Oars were shoved out, the water boiled under the thrash of the long, heavy blades, and the beautifully designed craft went sweeping away towards the open lake, pursued by demoniacal shouts and trumpet blasts from the empty launch.

It was not until the long-ship was out of sight that Martin at last turned a wondering face to the Professor.

The latter smiled indulgently.

"Quite simple," he said. "A gramophone with a megaphone attachment. As for the order, those were the only few words of the Lemurian language which we knew. They mean something like 'Run for your lives.' I had arranged it so as to be able to switch it on from here, and I may add that if it had not worked, I had a few more surprises up my sleeve."

Martin burst out laughing.

"Bully!" he exclaimed. "The poor devils! They must have thought that the most awful magic they had ever run across. I'll bet they'll never come back."

"Don't be too sure about that," replied the Professor gravely. "Remember, Martin, these men are not savages. They have enormous pluck, and although their superstitious fears have got the better of them for the moment, I will warrant they will try again."

He stopped short, raising his hand for silence.

"What's that?" he said sharply.

Before Martin could reply there came a loud and desperate shout from above. "Help, Marse Distin! Help, boss!"

"It's Scipio," muttered the Professor, and was off up the great staircase with a speed surprising for a man of his years.

AS Martin raced up the smooth steps he heard a heavy thud and a ringing clatter of metal. He passed the Professor, and ran at full speed between the tall, sculptured columns in the direction of the sound. The Professor having switched on all the electrics, the great hall was as light as day.

"Dis way, Marse Vaile!" came a shout from Scipio; and, as he rounded a great columned pillar, Martin saw in front of him the negro battling desperately with one of the golden giants. Scipio, who was a burly man still in the prime of life, was armed with a tremendous club. That he had used it well was proved by the fact that one of the enemy lay flat upon the rock floor of the hall. The second, however, was pressing him hard, driving at him with his short but deadly-looking sword.

How the Lemurians had got there, or what had happened, there was no time to inquire. All that Martin saw was that Scipio could not last another moment. Swinging his battle ax high in the air, he dashed recklessly into the fray. The great Lemurian, busy with Scipio, did not see the boy coming. When he turned, to see him, it was too late, for Martin had him at his mercy. Yet even in that moment Martin did not forget what the Professor had said about not killing the Lemurians, and it was the blunt back of his ax which smote the tall foeman on the top of his head, and sent him rattling in his armor to the floor.

"Quick, boss!" panted Scipio. "Dere's more a-coming. See dat hole under de pillar? Dat's where dey's coming up. Yo' help me to shut de door."

Martin saw in a flash. At the base of the great carven columns gaped a dark opening which had been covered with a slab of stone. This was now leaning against the pillar. Together he and Scipio flung themselves upon the slab. It was desperately heavy, and took all their strength to move it.

Martin had hardly got hold of it before he felt his left leg grasped by a huge hand. He yelled to Scipio, and kicked out desperately. It was useless. He was plucked away as a lion might seize a dog, and the next instant was dragged down into the depths of the pit.

For a moment Martin had a horrible sensation of falling, dropping into unknown depths. Then he was caught—caught as easily as a child might catch a kitten—in a pair of giant arms. He heard a hoarse cry of triumph, and looking up saw, red in the smoky glare of torches, a face more terrible than any he had ever pictured in his wildest dreams.

It was the face of a giant with a nose resembling an eagle's beak, and fierce eyes gleaming like pale steel. The golden heard was turning gray, and the hair was long and gray under the heavy helmet. But it was the mouth that was the worst feature of all. Wide, with thin lips, it showed teeth like those of a wild animal, and by some curious malformation of the upper jaw the eyeteeth on each side projected outside the lower lip, like the tusks of a walrus.

The owner of the face was nearly seven feet high, and had a chest like the gnarled trunk of an old oak.

For a moment he held Martin in both hands, glaring at him with a look of such malice and savagery in those evil gray eyes as made the boy cold to the bone. Then, with a deep laugh, the monster swung him lightly over his shoulder and went striding away down a long, sloping tunnel. Martin had little time to think. His captor went on at a tremendous pace, and he, hanging like a sack over the giant's shoulders, was bumped and swung till his head swam. A few moments only, and they came out on to a narrow ledge of rock just above the level of the lake.

For a moment he held Martin in both hands.

Lying tied to the ledge was a boat, a sort of shallop, broad and solid, but with low sides. Into this the big man stepped, dumping Martin down in the bottom as unceremoniously as a sack of coals. The next thing that he knew was that the boat was bumping alongside the longship in the open lake.

The tusked giant stooped, grasped him, and, as he swung him up into view of the crew of the longship, the crew burst into a long-drawn shout of "Haro! Haro, Odan!"

Next moment he was pitched into the longship, and found himself lying on the bottom boards between the two benches on which sat the rowers. A fresh roar of triumph from every throat. Then a stern command from Odan, who was evidently the captain of the Lemurians, and the strangely shaped craft sped away towards the mouth of the sea loch.

Left to himself for the moment, Martin tried to pull himself together, and think what was best to be done. For the life of him he could not see any way out. True, the Lemurians had not tied him, but that did not help. Even if he could seize a chance to spring overboard, they would have him again at once. In any case, the ship was by now a long way from shore, and he had no notion whether he could reach it.

The more he considered matters, the more helpless seemed his position. He knew, of course, that the Professor and Scipio would do all in their power to rescue him, but he could not see how one frail old man and a negro could do very much. They had nothing but the little launch, which would crack like an egg-shell under the driving weight of the Lemurian ship.

Even if Professor Distin were to resort to firearms it would be next to impossible to pick off enough of these many rowers, protected as they were by their thick shields, to cripple the longship.

His heart sank, and with every stroke of the oars he came nearer to despair.

After a while Martin tried cautiously to raise himself so as to see where they were going. His movement was noticed, and a rough hand seized him, shook him, and flung him down again. His blood boiled, but, knowing the utter uselessness of resistance, he lay still.

The sound of the oars changed. The beat was echoed back from cliffs, and Martin knew that the ship must be fast approaching the narrow channel leading to the sea. At the same time he noticed something else. A slight mist was dimming the stars overhead. It thickened so rapidly that even the mast-head of the longship was scarcely visible. He heard an angry growl from Odan, the oar beats slackened, and the longship moved more slowly.

Martin was amazed. Fog on a night like this, and on a warm, almost tropical sea, was a very strange phenomenon. Every moment it grew more dense, and now Martin realized that this was no ordinary mist. It was smoke! He could smell it.

His thoughts flew at once to the volcano. Was this smoke beating down from its lofty crest? or was some fresh eruption beginning? He knew that the great cone was far from extinct; and the Professor had spoken of earthquakes from time to time.

The smoke became so thick that Martin could hardly see a yard before him. It reeked of sulphur. His eyes were streaming, the foul stuff was in his lungs, and he was choking for breath.

Suddenly the gloom was lit by a dull glare of light which seemed to be dead ahead. A moment later came a heavy thudding explosion, the water boiled, and the longship pitched heavily on a series of great, swelling waves. Now Martin was sure that he was right. A volcanic eruption had begun.

Another bump! Then all of a sudden the men around Martin tried to scramble to their feet, and he heard hoarse cries of terror. He himself made an effort to scramble up, and this time no one stopped him. Then, through the reek, appeared a face so hideous that Martin stopped, appalled. With its vast snout, from which hung down a curious tube, it was like nothing human.

It made no sound; but a pair of hands stretched out towards Martin, and, to his utter amazement, they and the arms above them were black!

In a flash he understood. This was Scipio!

He could have shouted with sheer delight, but had no breath. He could only choke. But he knew now, and scrambled up. The hands grasped him firmly, and drew him to his feet.

Half-choked and poisoned as they were, the Lemurians had no intention of parting so easily with their prey. With a hoarse cry of rage the great Odan lunged forward, seized Martin's arm with his monstrous hand, and began to drag him away. Then, from behind Scipio, another hand shot forward. It did not touch Odan, but in an instant he gave a choking bellow of pain and rage, his hold on Martin relaxed, and he staggered back flinging both hands up to his face.

Before he could recover, Scipio had dragged Martin clear, and the two were over the gunwale of the longship and in the launch. Like a flash the light little craft spun round in her own length, and darted away in the opposite direction.

The launch was in the cove harbor and safe inside the water gate before Martin was well enough to speak. Even then the Professor would not let him talk, and Scipio had to help him up the stairs and through the Painted Hall.

Lying in a long chair in the rock-roofed living room, the boy rested and drank a draught which the Professor prepared for him.

"I thought it was the volcano starting up," was the first thing he said.

"I don't wonder," replied the Professor, with his dry little smile. "As a matter of fact, I was taking a leaf out of Admiral Roger Keye's book, and using a mixture of phosphorus and sulphur which produced a dense artificial fog similar to what the motor launches spread in the attacks on Ostend and Zeebrugge."

"It was jolly smart of you," said Martin heartily.

"It was the only thing to do, Martin. Perhaps, after such a lesson, the Lemurians will leave us alone for a time."

"They'll be fools if they don't," replied Martin, laughing.

Then he started up. "But I say, Professor, what about the prisoners?"

The Professor got up quickly. He looked grave. "Upon my word, Martin, I had completely forgotten them."

"Scipio!" he called.

There was no answer.

"Ah, Scipio has remembered," continued the Professor. "No doubt he has gone to tie them up. Let us go and see."

They hurried into the Painted Hall; but before they had gone many steps, Scipio himself was seen hurrying to meet them.

"What about the prisoners, Scipio?" asked the Professor quickly.

"Dat's jest what I was coming to tell you about, sah. One of dem is dere whar Marse Martin laid him out wid dat battle ax, and I've tied him jest to make sure. But de oder, de one I knocked down, he's done gone. I can't see him no whar."

The Professor looked at Martin; Martin looked at the Professor. Both faces were grave.

"This is a bad job, sir," said Martin. "Where can he have got to?"

"Dar ain't no doubt about dat, boss. He's gone down dat dar tunnel hole. Me and de Professor, we put de stone back, but he's done lifted it again, for it's a-lying dar on its side."

"Then he has taken to the lake and probably swum after the longship," said the Professor. "But we must make sure. Let us arm ourselves, and take lights, and go down the tunnel." A few minutes later Martin stood once more in the gloomy tunnel through which he had been carried as prisoner little more than an hour earlier. Scipio was with him; but the Professor had remained behind in the Painted Hall.

The two went quickly out on to the ledge by the water's edge, and Martin looked round in every direction. There was not a sign of any living thing to be seen.

Martin turned to Scipio. "The man can't have swum very far, Scipio," he said. "And, personally, I don't believe he would have been fool enough to try to follow his friends that way. If he did swim out, he has probably landed again in some little cleft near by."

"I don't know as he's been swimming at all, Marse Martin," responded the negro.

"How do you mean, Scipio?"

"Why, sah, I mean be might hab climbed up dem dar rocks. Yo' look whar I'm a-pointing."

Martin looked. Sure enough, there was a sort of cleft—what Alpine climbers call a chimney—up which the Lemurian might very well have forced his way.

"Yes," said Martin slowly. "It's quite likely you're right, Scipio."

As he spoke he moved forward along a narrow ledge which led to the foot of this curious cleft.

"I wouldn't go out dar, Marse Martin," came Scipio's voice from behind him.

"Why not?" asked Martin, turning.

The movement saved his life, for at that very instant there was a loud rumbling sound overhead, and with a rattle of loose stones an enormous boulder, flung from some unseen height above, came whizzing down. It missed Martin by a mere matter of inches, and plunged into the inlet, flinging up a fountain of foam ten feet into the air.

NEVER in his life had Martin moved so quickly as in the next few seconds after the fall of the stone. He was back beside Scipio in three jumps, but, quick as he was, a second rock was on its way down before he was actually in safety.

"Dat fellow sure want to kill us mighty bad, Marse Martin," Scipio remarked.

"If you hadn't called to me when you did, he would have killed me, Scipio," replied Martin. "I only just turned in time."

"Well, he didn't git you, sah, and I reckon he won't now," he added quietly. "All de same, it ain't no fun to hab one o' dese here wild men a fossicking round loose all ober dis old island ob ours."

"You 're right there, Scipio, it's no fun at all. And it's not going to be fun for any of us until we've got him safely boxed. Strikes me we'd best go back and ask the Professor what we are to do."

The Professor was very much disturbed at the tidings which Martin brought him.

"I don't know what we are to do," he said, shaking his head. "The garden and orchard will be at the Lemurian's mercy. This island is full of hiding-places of which he can take every advantage."

"Don't worry, sir," said Martin. "I'm sure we shall find some way of tackling him. The great thing is to make sure that he can't get in here."

"Quite so. Scipio knows all the entrances. Go round with him and see that all are closed. As for this trap-door in the Painted Hall, we can make it safe by rolling a rock upon it."

"Hadn't we better tie up this other Lemurian before I go?" suggested Martin, anxiously.

The Professor smiled.

"No need for that. The unfortunate man is still insensible. You must have hit him pretty hard, Martin."

"Not too hard, I hope, sir."

"Oh, no! His skull is fairly solid, and he will pull round. But he has concussion, and is not likely to be troublesome for some days to come. Now go and see to the doors."

Ten minutes later Martin was able to report to the Professor that it was quite impossible for anyone to get in.

"Very good," said the Professor. "Now you and Scipio can help me to put this man to bed, and after that you had better get some sleep. I foresee a busy day tomorrow."

The Lemurian was young and not so huge as most of his fellows, yet even so it was as much as the three of them could do to carry him to a room, and put him to bed.

This done, the Professor ordered Martin to bed again, and Martin was not sorry. He was sore all over from the handling he had had that night, and, once he got off to sleep again, never moved until he woke, with the sun blazing through the long window of his room, full in his eyes, and Scipio standing beside him, with a cup of delicious hot chocolate on a tray.

"Bath ready, sah," announced the good fellow. "Yo come wid me. I show you whar he is."

The bath was in a rock chamber behind the bedrooms. A stream of water came pouring through the roof into a great rock basin. It was crystal clear and icy cold. Martin fairly revelled in it, and came out with a keen appetite.

"And now, Martin," said the Professor, when they had finished a hearty breakfast, "the next thing is to devise some plan for capturing our enemy. But how it is to be done I confess I have not the faintest idea. If we start out afoot the chances are we shall find ourselves the hunted instead of the hunters."

"I should think we should, sir," Martin answered. "The chap is as strong as all three of us put together. He can move like a cat, jump like a goat, and swim like an otter. Into the bargain, I expect his senses are a lot keener than ours."

"I agree with every word you say, Martin," said the Professor. "Yet I do not see any alternative. Do you?"

"Yes," replied Martin, "I do. I've been thinking it over, and it seems to me that our best plan will be to hunt him from the air."

The other looked up quickly. "Your aeroplane, you mean? I never thought of that. Undoubtedly you are right." Martin lost no time in getting aboard his plane.

The great twin engines roared, and the echoes thrown back from the rocky roof were deafening as the graceful machine taxied swiftly down the tunnel, through the fiord, and so into the open lake.

Once outside, Martin opened the throttle to its widest, and, tearing across the smooth surface, pushed over the control, and found himself lifting lightly into the sunny air.

Turning his head he caught a glimpse of the Professor and Scipio just shooting out from the fiord in the launch. In a moment it had dwindled to the size of a toy, and Martin was wheeling upwards in steep circles.

His idea was to cruise about at a moderate height, and endeavor to get sight of the Lemurian.

Very soon he was above the tall cliffs, and sailing over the lower slopes of the great peak in the foot of which were the caves. Above him the snow-clad mountain towered against the blue, like a cone of icing sugar. On the far side of the lake the twin mountain stood up steeper and darker, with its trail of volcanic smoke drifting lazily before the wind.

Martin flew back over the range of caves, and presently caught sight of a long shallow valley down the center of which a stream poured in little waterfalls. The ground on either side was terraced and vividly green.

"Ah, that's the garden," he said to himself. "Now, I wonder if the man is there?"

Twice he circled over it, dropping lower. But there was no moving thing, to be seen, and, rising again, he began to search the whole mountain side, quartering to and fro just as a kestrel hawk hunts across a meadow for field-mice or voles.

Half an hour passed, and Martin had seen nothing moving except birds, rock rabbits, and once a great snake trailing its shimmering coils across the rock. He turned north, and began searching that side of the peak.

Here the slope was steeper and wilder. There was little in the way of shrubs, and the only green he saw was strips of grass lining the banks of the many little torrents which came tumbling from the heights.

"Hardly likely that he's there," he said to himself; and banking steeply, came round again. As he came round he suddenly caught a glimpse of something moving far up against the steep mountain side. Mere dot as it was he realized that it was something living and something larger than he had yet seen.

Instantly he swung towards it, and his heart gave a great throb.

"It's he," he gasped—"the man himself! But what, in the name of all that's wonderful, is he doing up there?" It was the Lemurian. Of that there was no doubt whatever. As the plane flashed towards him, Martin could clearly see the sun's rays reflected from the gold on his helmet and corselet, and very soon he saw something else.

Every other moment the reflection from the golden armor was cut off by a great, dark shadow which passed to and fro.

Martin was puzzled.

"Something is attacking him," he said in a low voice. "But what can it be? What creature, except a goat or a mountain sheep, could live on these heights?"

The Bat devoured the distance at, the rate of a mile and a half a minute, and it was only a matter of seconds before the puzzle was solved. It was no wild beast that was attacking the Lemurian, but a bird; a bird of such monstrous size that it made Martin blink with amazement.

Standing on a ledge, with his back against the sheer rock, the golden giant defended himself bravely with his short sword against the attacks of his enemy. But, big as he was, the bird fairly dwarfed him. Judging roughly, Martin thought that the creature must be at least twelve feet across the wings, and the swift fury of its swoops made him see how fearless and formidable an enemy it was.

Martin wondered what on earth he could do. Naturally, it was impossible to land. It seemed to him that the only thing to do was to fly past as closely as possible, and endeavor to draw off or frighten the huge bird of prey.

He had not much time to consider. Traveling at such speed, he was on the scene of battle in a few seconds. Just as he came swirling up he saw the bird make a fresh dash, and this time its attack appeared to succeed. The Lemurian swayed, staggered, and, falling over sideways, lay motionless on the ledge.

"Poor fellow!" muttered Martin. In spite of the fact that the man had done his best to kill him on the previous evening Martin felt a pang of real sorrow.

Next moment Martin's own hands were full, for the bird, swinging past the fallen man, had sighted the plane, and turned upon it with fury.

"Takes me for another bird," Martin said aloud. "Well, he'll learn the difference." As he spoke he drew his pistol from its holster.

The eagle was coming for him straight as a bullet, and with a speed equal to his own. Martin realized that if the bird got mixed up in the plane, the results might be very serious indeed. Its weight and bulk were so great that it might easily break a blade of one of the tractors, in which case the Bat would be helpless as far as flying went.

In order to avoid this danger, he banked sharply and swung out widely from the mountain side. Quick as he was, his enemy was as quick. It struck the right hand upper plane, and Martin saw with dismay that a long strip of the canvas had been torn away.

"The brute!" he cried, and flung the plane into a swift dive.

For the moment he lost sight of the bird, but only for a moment. Then it was at him again. Pulling his control towards him, he shot up again. This brought him abreast of his adversary, and instantly he let fly with his pistol. The shooting seemed to drive the bird frantic with rage, and it came at him like a thunderbolt.

By the smartest possible manouevering he just managed to avoid its onslaught; but the next moment he got a fresh shock, for here was the bird attacking him from the other—that is, the left-hand—side. As he swerved once more to avoid it, he saw, to his horror, that it was not the same bird, but another, even larger than the first.

"A pair of them!" he gasped. "This looks ugly!"

THE odds were too great. In a flash Martin saw that his only chance of safety lay in flight. Pushing over the control he let the nose of the Bat dip sharply, and, at the same moment opened his throttle to the widest. Instantly he was swooping lakewards at terrific speed.

In an ordinary volplane, or dipping flight, the pilot shuts off his engine completely. Even then the pace is tremendous. Imagine, then, what happens when you are not only dropping, but driving at the same time with the whole of your engine power.

Never since he had first handled a plane had Martin traveled so fast. The air howled past him like a hurricane; beneath, the rugged mountainside shot away like a cinema film. The strain on the Bat's planes was terrific. Martin knew well the heavy risk he was taking, yet, aware of the eagles' powers of flight, he realized that this was his only chance to get away. He ventured to glance back, and there were the two giant birds hurtling in pursuit. But even their marvellous wing power did not equal those of the Bat. He was escaping rapidly.

But he was getting dangerously close to the surface of the lake. To hit it at anything like this speed meant certain destruction. He switched off his engine, flattened out, and alighted.

Once more switching on his engine, he started "taxying" across the lake towards the mouth of the Tunnel Cove.

He had had some sort of hope that, once he was on the water, the eagles would leave him. Nothing of the sort. Almost before he had started they came swooping down at him.

But now Martin was in a better position to deal with them. For the moment he could leave the plane to take care of itself. Snatching up his automatic, he opened fire upon the first of the great birds of prey, which was close upon him. One of the bullets struck it full in the breast, and down it came upon the water, thrashing the calm surface into foam with its wings.

An automatic is like a machine gun. It goes on firing as long as the finger is pressed on the trigger. As Martin swung round to fire at his second assailant the rapid explosions ceased, and he realized with a thrill of horror that the magazine was exhausted.

The second eagle—the female, and the larger of the two—seemed roused to fresh fury by the downfall of her mate, and came at Martin like a bolt shot from a catapult. He did the only thing possible—flung himself down at the bottom of the "nacelle," or hull, of the flying boat, and lay flat, while he feverishly strove to thrust fresh cartridges into his pistol.

He felt the wind of the vast pinions as the bird swung just above him, heard a rending tear as her hooked talons ripped the canvas of the plane just overhead, and knew that her first swoop had missed.

Then came a fresh misfortune. In his hurry he jammed the pistol. A cartridge stuck half in and half out. The weapon was useless. It was hardly likely that the eagle would fail a second time.

Nothing happened, however—at least, nothing happened to Martin, yet he could still hear the beating of the great bird's wings. He could also hear a splashing sound, and at the same time was conscious of a curious harsh, musky odor.

After a moment or two curiosity got the better of fright, and he ventured to raise his head and look round. The sight that met his eyes nearly paralyzed him.

Out of the deep water of the lake had risen something that looked like the head and neck of a great snake, and between this new horror and the eagle a battle royal was raging.

Petrified with amazement, Martin stared at this marvelous combat. The engine had stopped, the tractors had ceased to revolve, but Martin never thought of pressing the electric starter again. He utterly forgot his own danger in watching such a sight as perhaps no human being had seen since the dawn of man's history.

The first thing he realized was that the water beast was not a snake. The head and neck were more like those of one of the snapping turtles which are common in all tropical waters. The neck looked as if cased in loose leather, while the head was purely a turtle's with a wide mouth armed with jaws of solid bone. Then he saw, beneath the surface, the body of the monster shaped like a monstrous dish-cover and plated with a greenish shell.

The creature's head flashed this way and that in movements so quick that he could hardly follow them, while its beak-like jaws kept snapping together with a harsh clipping sound. Its eyes, with raised horny lids like those of an alligator, had an indescribably vicious gleam.

Quick as it was, the eagle was quicker. Martin could not help admiring the dauntless pluck with which she hurled herself against this fearful enemy, buffeting the monster with her powerful wings and slashing it with her great curved beak. Good blows, too, for dark red blood was already dripping from the head of the huge fish-lizard.

The lizard rose higher in the water, so that its vast domed shell came above the surface. Waves washed against the hull of the Bat, the reddened foam splashing right over the coaming. Its thick tail rose, lashing the surface of the lake; and Martin felt that a single stroke would be enough to smash his frail craft and sink it.

Then what chance would he stand, swimming for his life in water haunted by such terrors?

Martin jumped up and pressed the electric starter. There was a splitting sound, but nothing happened. For some reason unknown, the engine refused to fire.

He set to work with desperate energy to find out what was wrong, while the Bat heaved and swung upon the swells flung up by the titanic struggles of the water monster. At any moment the fight might swing down upon him. Or if either of the fighters won, the survivor would, he felt, be certain to turn upon him.