RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

Dust Jacket of "Luck or Pluck,"

F. Warne & Co., London & New York, 1930

Cover of "Luck or Pluck,"

F. Warne & Co., London & New York, 1930

Title page of "Luck or Pluck,"

F. Warne & Co., London & New York, 1930

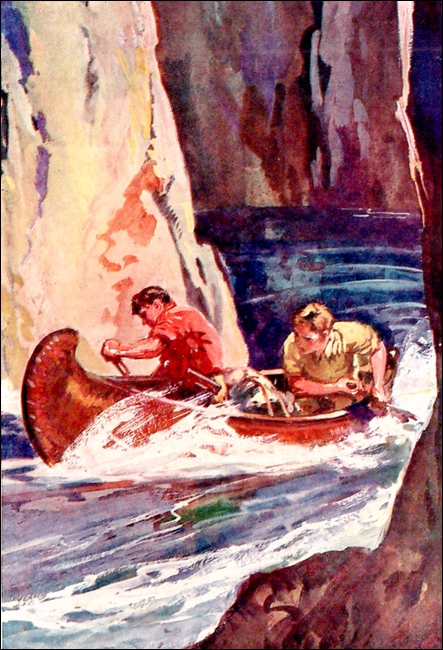

Frontispiece.

They had the canoe travelling at full speed

before they reached the foot of the rapid.

"DASHED unfair, I call it," complained Clive Winslow, as he looked at the letters lying on his cousin's plate. "Two for you, Bruce, and not a blamed thing for me."

Big Bruce Lyndall looked up with a twinkle in his grey eyes.

"Don't be an ass, Clive. Here, read Mother Morell, while I see what dad's got to say."

The long table was packed with boys of Overton School, all busy with their breakfast and talking sixteen to the dozen. It was only two days to the end of the summer term, and every one was wildly excited at the idea of getting home for the long eight weeks' vacation. Bruce, by reason of being a dormitory captain, sat at the head of the table, and Clive next to him, so they were able to read their letters in peace.

Bruce's letter bore a Canadian stamp, and the contents interested him so much that he never noticed the queer look which spread across Clive's thin, clever face as he read the other letter. Presently Clive looked at Bruce and seemed on the point of speaking. Then he changed his mind, folded the letter, put it back in its envelope, and started quietly on his bacon and bread and butter. But, if Bruce had been watching him, which he was not, he would have seen that Clive was not eating with much appetite.

At last Bruce finished his letter.

"Lots of news, Clive," he said, in his deep voice. "And dad's sent two fivers, one for me, the other from Uncle Quentin for you. We shall be able to do ourselves proud these hols." He broke off. "Hallo, what's up?"

"Tell you afterwards," said Clive in his quiet way, and Bruce merely nodded.

The two cousins understood one another remarkably well. Both finished their food as quickly as possible and went out together. They made straight for the small study they shared, and nothing was said until Clive had closed the door. Then he looked Bruce straight in the face.

"Masters is dead," he said.

Bruce's big powerful frame stiffened.

"Dead!" he repeated.

"Yes, Mrs. Morell says he had a heart attack on Monday and died quite suddenly. Read it."

Bruce took the letter and glanced through it thoughtfully.

"This is a nice mess-up, Clive. To be quite honest, I'm not thinking of the poor old boy, for after all he didn't enjoy life much, and I dare say he's glad to get out of it. But it's left us in a hole."

Clive nodded. "I see what you mean. We can't go back to Chilton. Mrs. Morell says the house will be sold. I suppose it means we shall have to stick here at Overton for the hols."

Bruce's lips tightened. "I'm not going to do that," he said flatly.

"There's no choice, old man. Even if we cabled to our people we shouldn't hear for ages. It takes two weeks for a letter to reach Last Chance from rail-head. The hols, would be half over before we could hear."

"I know that as well as you do," said Bruce. "We must just shove along on our own."

Clive stared. "You mean go out to Canada?"

"That's the notion," replied Bruce calmly.

"But how are we to get the money? We should want about fifty quid, and the Head will never run to that."

Bruce grinned. "I'd like to see his face if I asked for it. No, we won't say a word to Doodle. Why should we? We've got this ten quid and about five more saved up. That's fifteen. Then there's all our stuff at Chilton—guns and golf clubs and the rest. My notion is to sell what we don't want. We ought to get twenty pounds easily, and thirty-five pounds will be plenty to get us across, steerage, and pay our rail fare the other end."

Clive's eyes widened as he listened. Clive was a slim youngster, much more lightly built than his big muscular cousin, but much more highly strung. He had more brains than Bruce and beat him easily in class, but Bruce had a way of going straight to the heart of things which sometimes made Clive gasp. There was a twinkle in Bruce's eyes as he watched his cousin.

"Any objections, Clive?" he asked presently.

"A lot," said Clive gravely. "Even if we do get enough money to reach rail-head at Tequam, we don't know the way from there to Last Chance."

"We'll find that easily enough," declared Bruce.

"Suppose we do, that trip alone takes a fortnight. By the time we get to Last Chance half the hols will be gone, and we shall have to turn straight back if we want to be here in time for next term."

"We don't," Bruce answered. "I don't anyhow. I wrote to dad weeks ago that I wanted to leave at the end of next term, and he said I could if I liked. One term doesn't make much odds, does it?"

"N-no, I suppose not," agreed Clive. "And of course if you leave I shall. All the same I'm rather wondering what your dad and mine will say when we turn up at Last Chance."

"That's the last thing you need worry about," said Bruce promptly. "They'll be jolly glad to see us."

"Why?"

"Because they're in a hole of some kind. No"—as he saw the anxious look on Clive's face—"dad doesn't say it in so many words, but I know from his letter there's something wrong."

Clive's lips tightened. "All right, Bruce," he said quickly, "I'm with you."

Bruce's big hand dropped on his cousin's shoulder.

"I knew you'd say that, old man. Then not a word to anyone until we're safe on our way."

THE late Michael Masters had been the Lyndalls' family solicitor, and, when Mr. John Lyndall and his cousin, Quentin Winslow, had plunged into the wilds of Northern Ontario to work the gold mine which John Lyndall had discovered, he had taken charge of their sons. Masters was a grim old man, not the sort to make friends with a couple of schoolboys, but Redlands, his house at Chilton, was in open country, with plenty of fishing and boating, so that Bruce and Clive had managed to amuse themselves pretty well in the holidays.

They had also done very well at Overton School, where they had been for nearly four years, but for all that they never ceased longing to get back to Canada where they had been born. In all those four years they had only once seen their fathers, who had each been over for a short visit. Perhaps because they had lost their mothers when they were very small, they were both devoted to their fathers. The two were tremendous chums, more like brothers than cousins. Bruce was the brawn, Clive the brains of the pair, and between them they made a pretty useful team.

Once they had made up their minds to go to Canada their only fear was that Doodle, as they affectionately called Dr. Macdonald, might get wind of their plan and stop them. But evidently the Head had no suspicions, for he handed them over their tickets for Chilton, and wished them good-bye just as he had done every other term.

Chilton was a long way from Overton, and it was nearly tea- time when they reached it. They left their luggage at the station and walked, each carrying a handbag. When they reached the house the blinds were down, and the place had a gloomy, deserted air. The front door was locked, and at first there was no answer to their ring. At last they heard some one unbarring the door, and both got a shock when, instead of Mrs. Morell, a large, sour- faced, unshaven man looked out.

"What do you want?" he asked gruffly.

"Where's Mrs. Morell?" asked Bruce.

"She don't live here," returned the other.

"Of course she lives here," retorted Bruce. "She's Mr. Masters's housekeeper."

"He's dead, and she's left," was the curt answer.

"Where has she gone?" inquired Bruce.

"I don't know, and I don't care. And I don't want you boys bothering me."

He made to shut the door, but Bruce pushed in.

"Steady on," he said. "We lived with Mr. Masters, and we've come for our things."

"I don't know nothing about your things," replied the man doggedly. "I'm put here by Mr. Claude Masters to see as nothing is took from the house. If you wants anything you got to get a written order from him."

"Claude Masters!" exclaimed Bruce. "That's old Mr. Masters's nephew? Where is he?"

"In London," replied the caretaker, and then he suddenly gave Bruce a sharp push and slammed the door in his face.

Bruce was furious, but Clive caught him by the arm.

"It's no use making a fuss," he said, in his quiet sensible way. "The man's got the law on his side, and we must get the order before we can touch our stuff. Best thing we can do is to try to find Mrs. Morell. Let's go and see old Sladen at The Swan."

Bruce allowed himself to be persuaded, and they went off to the little hotel where George Sladen received them kindly and offered to put them up. But the news he gave them was bad. Mrs. Morell had left for her old home in Westmorland, and he did not know the address of Claude Masters.

"And, if I did know it, I don't reckon it would be much good to you," he said. "He come down for the funeral, and never did I see a harder-faced chap. Why, the old gent who died was a angel compared with him."

"Sounds healthy," said Bruce bitterly, as he and Clive sat together in the stuffy little parlour after supper. "It may take a week to find this Claude person, and by that time we shall have spent all our cash. I've a jolly good mind to go out to Redlands to-night and collar our things."

"Don't be an ass, Bruce," said Clive gently. "If you try any game of that sort we shall spend our holidays in prison."

"Then what are we to do? Go and beg Doodle to take us back?"

"Nothing of that sort. I vote we go straight to Liverpool."

"What's the use?" asked Bruce despondently. "Even a steerage ticket costs ten quid."

Clive remained calm.

"Carruthers lives in Liverpool," he said, and Bruce fairly jumped.

"I'd clean forgotten that. And his dad owns ships. You mean we might get a cheap passage?"

"No, but a chance to work our passage," replied Clive.

"A jolly good notion," agreed Bruce warmly. "We'll be off first thing in the morning."

They caught an early train, got to Lime Street Station about eleven, and, leaving their things in the cloak-room, made their way to Sefton Park where their school friend, Geoffrey Carruthers, lived. The house, big and comfortable-looking, stood in fine grounds, and their spirits rose as they walked up the drive.

"Give old Geoff a bit of a shock, when he sees us," chuckled Bruce, as he rang the bell.

The door was opened by a butler who looked at the two boys in some surprise.

"We are from Overton School," Clive explained. "We want to see Mr. Geoffrey Carruthers."

"He's not at home, sir," replied the man politely.

"Not at home!" repeated Clive. "When will he be in?"

"Not for some weeks, sir. The family left for Scotland last evening." Then, seeing the dismay on Clive's face: "Is there anything I can do?" he asked kindly. "Any message I could send on?"

Clive pulled himself together.

"Thanks very much, but I'm afraid not. Come on, Bruce."

"Now we're properly in the soup," said Bruce grimly, as they reached the road.

But Clive refused to be discouraged.

"There's still a chance we might pick up a job. Let's go to the docks and look round. A lot of ships sail to-morrow."

The dirty yellow river was crowded with shipping; the narrow streets were packed with vans and trolleys. Everything was noise and confusion, and the boys had no idea where to go or what to do. They stopped by a little eating-shop, and the smell of frying sausages reminded them that they had had nothing to eat since an early breakfast.

"Let's get some grub," suggested Bruce.

Clive nodded, and they went in and ordered sausages and mashed. While they ate they talked.

"The best thing would be to find Carruthers's office," said Bruce. "They'd tell us what ships are sailing. What's the name of his line?"

"I think it's the Blue Funnel," said Clive, "but I'm not sure."

A man sitting opposite spoke.

"'Scuse me butting in," he said politely, "but was you asking for Carruthers's office?"

Clive looked at the man, who was youngish and wore a cheap blue serge suit with a muffler round his neck. He had a sharp, narrow face and hard, pale blue eyes. Clive didn't quite like the look of him and hesitated in replying, but Bruce spoke quickly.

"Yes. Do you know where it is?"

"Pity if I didn't. I works for 'em," said the man, with a grin. "You come along with me arter you've finished your grub, and I'll show you."

They finished quickly, and Bruce paid the bill. Then their new friend led the way down the street and up an alley—a dingy, dirty place, the heavy air thick with unpleasant smells.

"It's a short cut," explained the man, as he took them through a dark tunnel under some buildings. "Takes you in the back way. Who was you wanting to see?"

"We wanted to see Mr. Carruthers," said Bruce, "but he's away."

"You better see Mr. Beatty," said the man, as he stopped opposite to a door. "I'll find out if he's in."

He went in, leaving the boys standing in the narrow street. They waited for a long time, and at last Clive spoke.

"I don't believe this is the office at all," he said. "What's more, I've a notion that chap's a fraud?"

"What rot, Clive!" retorted Bruce. "It isn't as if he had anything to gain by leaving us here. What are you looking so worried about?" he added.

"The money. Is the money all right?" asked Clive sharply.

"Of course it's all right," said Bruce, as he put his hand into his breast pocket. Then an expression of almost ludicrous surprise crossed his face. "Why—why—where the mischief is it?" He began feeling in all his pockets violently. "I must have left it in that feeding place," he cried.

Clive shook his head. "No, Bruce. You didn't leave it anywhere. That fellow picked your pocket as we went through that tunnel."

Bruce stared at Clive stupidly.

"B-but it's all we had. We—we haven't a bob left, Clive!"

CLIVE felt in his pockets.

"Not even a penny left," he answered, and suddenly Bruce woke up and made a rush for the door through which the thief had disappeared. It was locked, but, though Bruce hammered and pounded on it till the place echoed, there was no answer. A roughly dressed man came out of a door opposite.

"What do you think you're doing of?" he demanded. "You stop that row, or there'll be trouble."

Clive caught Bruce by the arm.

"You may just as well chuck it, Bruce. That chap's far enough by now."

Bruce's grey eyes were blazing.

"But he's got our money," he exclaimed.

"And there's not one chance in a million of getting it back," said Clive, in his quietest voice.

"But what are we going to do?" For once Bruce was almost beside himself.

"Go back to the station and get our luggage. We can get a bed somewhere if we have luggage with us; then we'll start hunting for a passage on some ship."

Bruce looked at Clive. "We can't get our luggage," he told him. "The cloak-room ticket was in the wallet with the money."

Clive whistled. "That's awkward," he remarked.

"And it's all my fault," said Bruce bitterly.

"Don't talk rot," said Clive. "And don't get the wind up. This is the time we've got to keep our heads. The best thing we can do is to try to find Carruthers's office. If we tell them who we are we may be able to fix up something."

Clive's calmness had a good effect on Bruce.

"Anything you say, Clive," he agreed, with unusual mildness.

So Clive led the way back down the alley, and presently they found themselves again on the wharves. Suddenly Clive pointed to a big steamer lying in a basin just opposite.

"There's a Blue Funnel, Bruce. She's one of Carruthers's ships. The Ibis. I know they've all got names like that."

"And nearly ready to sail," added Bruce eagerly. "Suppose we go aboard."

"Right you are," said Clive.

He spoke quietly as usual, yet his heart was beating with excitement. They crossed a gangway and were met at the head by a quartermaster.

"Can we see the Captain?" Clive asked.

"He's not aboard," was the reply. "But there's Mr. Baring, the first officer."

The officer saw the boys and came up. "Anything I can do for you?" he asked kindly enough.

Clive hesitated. "We—we wanted to work our passage to America, sir," he said, with an effort.

Mr. Baring's eyebrows rose. "What's the trouble—run away from school?"

"No, sir," replied Clive. "Nothing of that sort. We were going out to our people in Canada, but we've been robbed. A man picked our pockets. Mr. Carruthers's son was at Overton School with us, and we thought perhaps that we might get a chance to work our passage on this ship."

Mr. Baring looked hard at the boys. He shook his head.

"We've no opening for anything of that sort, son," he said. "And, even if we had, you couldn't land without passports and money." Then seeing Clive's face fall, he went on: "But I'm sorry for your trouble. You'd better go round to the office and tell them who you are, and I dare say they'll lend you enough to pay your tickets back to Overton. The office is in Milton Street."

Some one called him, and he turned away. Clive looked at Bruce.

"Come on," said Bruce curtly.

But just as they reached the gangway a huge box van backed up blocking the way. The end was dropped, and a magnificent short- horn bull was led out. The great animal was very nervous and flatly refused to climb the gangway. At this moment a second van which was being started up back-fired with a sound like a pistol shot.

The bull, terrified, jerked back so sharply that the man who held the halter was pulled off his feet, and the animal, swinging round, rushed blindly along the wharf. The bystanders ran in every direction. Of them all Bruce was the only one to keep his head. In two jumps he was down the gangway and racing after the bull.

Bruce played three-quarters for Overton and for a big fellow was very fast. The bull was slipping and stumbling on the cobbles, but even so was travelling at a great rate. He was perilously near the edge of the wharf, but Bruce, spurting for all he was worth, managed to cut in between him and the edge. The bull was haltered, but unluckily the rope was trailing on the far side.

Bruce snatched off his hat and coming level with the bull slapped him with it across the nose. In sheer surprise the bull halted, and this gave Bruce the chance to get hold of the rope. The bull started again, and of course Bruce alone could not stop him, but the delay had given Clive a chance to come up, and he, too, grabbed the rope. Both were pulled off their feet, but they hung on like grim death and held the bull away from the wharf edge. More men ran up, but the bull dragged them all.

"Chuck a sack over his head," shouted Bruce, and one of them snatched a sack from a lorry and did so, and at once the great beast stood quiet.

"Now let go," said Bruce. "I'll take him back. And don't shout or make a row."

He spoke soothingly to the bull, and the creature quickly quieted down and allowed Bruce to lead him back. Bruce took him straight up the gangway on to the ship where a red-faced man with side-whiskers was waiting.

"Good for you, boy!" he said, in warm approval. "Lead him in here."

He showed the way to a big loose box on deck, the floor deep in straw, and Bruce took the bull in and fastened him up.

The red-faced man was waiting.

"Good work, son!" he exclaimed. "If old Trump had gone over the wharf it would have been fifteen hundred pounds out of my pocket, and he'd have gone, surely, if you hadn't been as quick as you were. Are you sailing in this ship?"

"No," said Bruce. "I wish we were."

The other looked hard at him.

"What's the trouble?" he asked straight out.

Bruce hesitated. He was getting tired of snubs, but the red- faced man seemed to understand.

"This isn't the right place to talk. That's what you'd like to say. If you and your friend will take a cup of tea with me we can have a yarn."

"Thanks," said Bruce briefly. "We'll be glad to."

The red-faced man, whose name, he told them, was George Gaunt, took them to a tea-shop and ordered a first-class tea, hot buttered toast, cake, and jam, and waited until the boys had got well to work before he began to ask questions. Then Clive told him the whole story. When he had finished Gaunt nodded.

"Your money's gone," he said. "You'll have to make up your mind to that. But we'll get your stuff from the station."

"The cloak-room ticket—" began Clive.

But Gaunt stopped him.

"I'm pretty well known here. I ship twenty thousand pounds' worth of prize stock yearly from this port. If I guarantee the Railway Company against loss it'll be all right. And there's plenty of time. The Ibis don't sail before nine to- night."

He called the waiter and told him to fetch a taxi. All three got into the cab and started for Lime Street. The driver took a short cut through a narrow side street, and suddenly Bruce gave a gasp and rapped the glass hard. Before the driver could stop Bruce was out and running like the wind.

"What's the matter? Has he gone crazy?" demanded Gaunt angrily.

But he found himself alone, for Clive, too, had leapt out and was helping Bruce to chase a mean-looking fellow who was running like mad, yet not fast enough to get away from Bruce who caught him from behind, wrapped his big arms round him, and fell on top of him.

"It's the thief," cried Clive, as Gaunt came up.

"And here's our money," said Bruce cheerfully, as he extracted a wallet from his prisoner's pocket—"most of it anyhow."

Gaunt burst into a delighted chuckle.

"You're the lads," he cried. "Keep your money, but let the wretched little pick-pocket go. He's had his lesson, and we haven't time to prosecute. Now get back into the cab before a crowd collects."

As the cab drove away they saw the thief pick himself up and go limping away. Gaunt laughed again.

"That settles it," he said. "You two are coming along with me. No, don't thank me. I'm a rich man, and your company will be worth anything I spend on you. A pair of lads like you will keep me happy all the way across."

BRUCE sat gazing out of window as the train rumbled northwards from Quebec. Clive beside him was studying a map. Some hours earlier the two had said goodbye to their kind friend, Gaunt, and to Trump, the big bull. Gaunt had seen them off from Quebec and before they left had made them a present of a hundred dollars. Not only that, but he had paid their railway fare to Tequam.

"You've got a long trip before you after you leave rail-head," he had said. "I shouldn't feel happy if you hadn't money for outfit." Then he added a word of warning. "You won't run into pick-pockets up there in the woods, but there are worse thieves and more dangerous. So keep your eyes open."

They had promised and were now fairly on their way. Presently Clive looked up.

"Bruce," he said, "when you got that letter from Uncle John you said there was something wrong at Last Chance. Any idea what it is?"

Bruce withdrew his eyes from the towering hill-side they were passing.

"No, Clive. It was just the way he wrote. I could feel he was out of spirits. It might be just that he wasn't well, or else he was anxious about something." He felt in his pocket. "You can read the letter if you like."

Clive read it carefully.

"I think he's ill," he said at last. "That's the notion I get." Then, seeing Bruce's worried look: "But it may not be much. You know how rotten one feels if one has just a toothache or a bilious attack. It can't be the mine, for he says the clean-up promises to be good."

"I hope you're right," said Bruce. "But I shall be jolly glad to get there and make sure all's well."

All day the train travelled first north, then north-west. At dawn the next morning the conductor told the boys that the next stop was Tequam, and the sun was just rising above the dark spruce forest when they found themselves standing on a little wooden platform while the train roared away in the distance.

"Here's the jumping-off place anyhow," said Bruce.

"Jumping-off place," came a drawling voice behind them. "I guess not. This here's a metropolis compared with Last Chance."

Both boys turned to find themselves facing a tall, spare man who wore a black flannel shirt and trousers tucked into heavy knee boots. His face was so weather-burned and seamed with wrinkles that it was hard to guess his age, and his hair was the colour of sand. But his grey-blue eyes had a glint of fun which made both boys feel happy.

"How do you know we're bound for Last Chance?" demanded Clive at once.

The tall man took a telegram from a pocket.

"This here says as two Britishers bound for Last Chance is to land up on the 17th. Seeing as there ain't but one train a day and you two is the only passengers as got off, it seems a good bet that you're the chaps mentioned."

Clive laughed. "Guilty," he said. "But it was jolly good of Mr. Gaunt to wire. Do you know our people at Last Chance?"

"You bet I knows 'em. I'm the postman. I reckon you're Clive, ain't you?"

"Right again," said Clive. "And this is Bruce. And you are—"

"Ricard, Bleak Ricard. You fellers better come along to my place and have some grub. We got to start in a hour."

"Are you coming with us?" cried Clive.

"That's right. Canoe's packed and ready. Arter breakfast we'll push right along."

He took them to his house built of squared logs and shingled. There was a store in front which was also the post office. In all there were only seven houses in the settlement. Mrs. Ricard, a bright-eyed French Canadian, had breakfast ready—hot corn bread, girdle cakes, fried pork, and coffee, solid fare but just what the boys needed in this keen northern air. Then Ricard showed them how to make up their stuff in waterproof packs; he provided them with blankets, and within an hour they were in the big canoe and driving away up the Vallier River.

The weather was perfect. Ricard knew every rock and rapid, and the boys soon learned to handle their paddles. Everything went well, and after ten delightful days they drove out quite suddenly into a long narrow lake of exquisitely blue water surrounded by low hills, and Bleak pointed to a landing on the right with a clearing behind, in which stood a solid-looking range of log buildings. The boys did not say anything, but the way the canoe leaped forward was good proof of their feelings. In almost no time they reached the landing and jumped out.

"Why, where's the folk?" asked Bleak, in a puzzled tone. "There ain't a soul in sight."

The boys exchanged startled glances and springing ashore raced up the slope. As they neared the house a tall Chinaman in a blue blouse came out and gazed at them in puzzled fashion. Bruce reached him first.

"Where's dad?" he demanded.

The man's eyes widened. "You Mister Lyndall?" he questioned.

"I'm Bruce Lyndall. Is my father at home?"

"Him home. No can go out."

Bruce did not wait. He tore into the house.

"Dad!" he shouted.

"Who's that?" came in a voice from a room to the right, and Bruce rushed in.

His father, looking white and thin, sat in a long chair with one leg straight out on a rest. He stared at his son as if he could not believe his eyes.

"You, Bruce! How did you come here?"

"That'll keep, dad. What's the matter with you?"

"I broke my leg a month ago."

"Then Clive was right. He said you were ill. Where's Uncle Quentin?"

A troubled look crossed Mr. Lyndall's face.

"I—I don't know, Bruce. He—he left three days ago."

"But you must know where he went," said Bruce, in amazement.

His father looked round. "Is Clive here?" he asked.

"Yes."

"Close the door. He mustn't hear what I have to tell you."

Bruce's heart sank. He had a sudden feeling that something was terribly wrong.

"Come closer," said Mr. Lyndall, and Bruce obeyed. "Listen," said the other, in a low voice. "Three days ago the whole of our clean-up of gold for the past six months disappeared, and—and your uncle went with it."

A LOOK of horror grew upon Bruce's face as he stood gazing down at his father.

"Dad," he said, "you're not telling me that Uncle Quentin stole the gold?"

Mr. Lyndall looked equally distressed.

"It seems impossible," he said despondently. "Yet I don't know what else to think. Hour after hour I have been lying here helpless, pondering over the business, until I have sometimes felt I should go crazy, yet for the life of me I can see no other explanation."

Bruce's lips tightened. "You'll have to tell me more. I'm not going to believe such a thing of Uncle Quen until I have to."

"You're sure Clive can't hear?" asked his father apprehensively.

Bruce glanced out of the window.

"No. He's talking to the cook. I say, that Chinaman won't tell him anything, will he?"

"That is not likely. Ching believes in your uncle as firmly as you do. There's no risk of his saying anything of my suspicions to Clive. In any case I've kept them to myself."

"That's good," said Bruce, in a relieved tone. "Now tell me."

"It begins a fortnight ago," replied his father, "when I took a tumble on the hill behind the house. I had been out after fresh meat and had killed a deer. I was carrying a quarter on my back when I slipped and fell and broke my right leg. Luckily I was within shouting distance of the house, and your uncle and Ching came out and brought me in. They put me to bed here and set my leg, and as it was only a simple fracture there was no need to fetch a doctor. I did not worry much, for Quentin could look after the mine, and Ching is a first-class nurse. We were just getting ready for the clean-up. You know from my letters that, once in six months, we melt up the gold we have mined into bricks and send it down to rail-head. Bleak takes it, and one of us goes with him to act as guard.

"This time the clean-up was the best we've ever had. There were five bricks each weighing twenty pounds. Since gold is worth a little over four pounds an ounce each of these bricks was valued at very nearly a thousand pounds. The clean-up was finished five days ago, and the bricks loaded up in the safe which is in the opposite room, to wait for Bleak's next visit. It is the room your uncle sleeps in, and when there is gold in the safe he keeps a loaded gun by his bed."

"Have you ever had any thieves about?" put in Bruce.

"Never. This country isn't like the West which is infested with bandits and hold-up men. We have only Indians and trappers about us, and very few of them, but at the same time we have always been careful and taken all precautions against theft."

"Are your men all right?" put in Bruce shrewdly.

"Absolutely. Peter Diggs, the foreman, and the other three have been with us from the start. You shall see them yourself. Now let me go on. Three nights ago I woke up suddenly. It was raining, but it wasn't the rain that had roused me. It was a sound inside the house. I listened a while, then called for Quentin. There was no answer. Then I rang the hand bell for Ching. No one came. I rang again; then I shouted, but nothing happened. I couldn't move, and there I had to lie till morning. Even then no one came, and I was just about frantic when Peter Diggs came hurrying into the house and wanted to know what was up. I told him and asked him to find Ching. Ching sleeps at the back in a little room over the kitchen. Diggs found him on his bed tied and gagged."

"Who'd done that?" asked Bruce sharply.

"Ching doesn't know. He says he found himself that way when he woke up. It seems plain that some one had given him a sleeping draught overnight."

"Perhaps he takes opium," suggested Bruce. "Chinese do, don't they?"

"Not Ching. He's as straight as they make them. But let me finish. Diggs and Ching went into your uncle's room and found the safe open and empty. It had been unlocked, not forced. And your uncle had gone. What is more, his hat, heavy coat, and rifle had also gone, and his canoe—the special one he always uses—was missing." He paused. "What can I think except that he took the gold?" he added, in a tone of despair.

Bruce's answer was prompt. "I don't think that, dad. I don't believe it for a moment. My notion is that the thieves seized him and took him along with them so as to throw suspicion on him."

His father shook his head. "I've thought of that, but it doesn't explain Ching being tied up."

Bruce stuck to his point. "That was done by the thieves. They might have chloroformed Ching."

"Chloroformed him," repeated Mr. Lyndall. "Yes, that is possible." Then his face fell. "But that does not explain your uncle's rifle and canoe disappearing."

"The robbers took them so as to make you think he was the thief," declared Bruce stoutly. "Very likely they had it all planned out beforehand."

The elder man's face relaxed a little.

"I only wish I could believe you were right, Bruce. I—"

Bruce held up his hand.

"Here's Clive," he whispered, and then the door opened, and Clive came in.

"What's all this, Uncle John?" he asked anxiously, as he grasped Mr. Lyndall's hand. "Ching says you've been robbed and that dad has gone."

"Yes," said Bruce quickly. "The thieves collared him and took him away with them as well as the gold."

"But why didn't you send your men after them, Uncle John?" Clive demanded.

"They are miners from the South," replied Mr. Lyndall. "Not one of them is any good in the woods. I sent one of them, Kerry, to the police post at Cross River, but he missed his way and came back this morning worn out and scared stiff. There is no one here who is fit to handle a canoe."

"Then it's up to us," said Bruce calmly. "We'll get Bleak to come along and run the thieves down in no time."

Mr. Lyndall stared at his son in blank amazement.

"Two boys like you!" he exclaimed.

Bruce smiled. "Dad," he said quietly, "we're not kids any longer. And we've had ten days' hard paddling. Of course we are still green to the woods, but with Bleak to help us we'll manage all right."

His father's eyes took in the big powerful figure of his son and the steady confident look on his face. Then he glanced at Clive's smaller, yet well-knit frame, and drew a long breath.

"Yes," he said slowly. "I do see that you are not children any longer, but as for your following the thieves that is a different thing altogether. You have no idea of the dangers and difficulties of our northern forests."

"You say your men are no good," said Bruce quietly. "If we don't go, who else is there to go?"

"We'll do it all right," added Clive confidently. "I'll go and talk to Bleak at once."

He went straight out, met Bleak coming up from the lake, and told him quickly what had happened.

"We're going after the fellows," he said, "and we want you to come too."

Bleak shook his head. "I'm mighty sorry, Clive. There ain't nothing I'd like better than to help you and your folk, but I ain't got the time for a long trip like this."

Clive looked dreadfully disappointed but pulled himself together.

"Then we'll have to go by ourselves," he said firmly.

"You can't do that, son," Bleak told him. "You can't read signs, and unless you can do that and follow a trail it would be easier to find a pea on a beach full of pebbles than a man in a wilderness nigh as big as all Europe."

BLEAK RICARD'S words hit Clive like a blow. He realised that they were true and that if he and Bruce started alone they would be helpless. The ground was knocked from under his feet, and he could find nothing to say.

Bleak saw the misery in the boy's eyes and felt intensely sorry for him. During their trip together the tall frontiersman had grown very fond of these two plucky, cheerful youngsters, and he hated to let them down.

"See here, Clive," he said, "I kin spare a month. Thet means two weeks out from here and two back. Now I don't reckon to catch these here thieves in a week and maybe not in a month, but I'll start ye on the job. I'll teach ye all I can of trails and signs, and arter I leaves you you'll hev to carry on alone. That's the best I kin do."

Clive's face lit up.

"It's splendid of you, Bleak," he said gratefully. "Just start us, and that's all we'll ask. When do we leave—now?"

"No," said Bleak. "There's a heap to do afore we kin start on a job like this. We'll hev our hands full to git away by sun-up to-morrow. Now I'll go and hev a talk with your uncle and get the lay of things as far as he knows 'em."

Bleak went into the house, and just as Bruce came out Ching called the boys to come in to dinner. Ching was a first-class cook and gave them broiled venison with fresh vegetables grown by himself and as a second course tinned peaches with custard. Bleak came in and joined them.

"I got it all fixed up with Mr. Lyndall," he said. "He's treating me real white. Paying me full wages and offering a reward of five hundred pounds if I gets the gold. I'd surely like to hev three months to spare instead of one. Soon as I've fed, I'm a-going down to the lake to look fer sign. Then I'll get the stuff together fer our trip. You boys don't need to worry. You better go and hev a good talk with the boss and cheer him up. He ain't heard yet how you come out here."

The way Bleak worked was wonderful. Before nightfall he had everything ready for a long trip—food, blankets, matches, rifles, and ammunition. Everything was done up in small packages and wrapped so as to be proof against the weather.

"They got to be like that so you can carry 'em easy over the portages," he explained. "And there'll be plenty of them afore we get to the top of the river."

"And what about sign?" Clive asked.

Bleak shook his head. "The rain's washed everything plumb away."

"Then how do we know which way to go?" asked Bruce, in dismay.

"They didn't come down the river, or we'd have seen 'em. So it stands to reason they went up. We must follow and take our chance of hitting the trail."

"Where do you think they're making for?" Bruce asked.

"Hard to say, but I'd make a guess it's Fort Nelson. That's a big port on Hudson Bay. They've got to get outside with their loot, and if they've gone north that's the only way out."

"But can't we send word there and have them stopped?"

A faint smile crossed Bleak's face.

"You're forgetting as we don't know who they are or what they looks like."

"But we can describe Uncle Quentin." Bleak shook his head. "They won't take him that far."

"What will they do with him?" Clive asked anxiously.

"Maybe they'll turn him loose when they think they're safe, or maybe they'll leave him in some Injun village. I don't reckon as any harm will come to him."

Clive looked happier, but later when Bruce went to say good- night to his father and told him what Bleak had said, Mr. Lyndall was troubled.

"I'd give anything to think Bleak was right," he said. "But if the thieves did carry away your uncle I don't see them letting him go. They would be afraid he might get in touch with the Mounted."

"Don't worry, dad," said Bruce. "With Bleak's help we'll catch them."

"I hope you will, my boy," replied the other earnestly. "I do trust you will. I only wish I were able to come with you. It troubles me to think of you two boys plunging into the unknown."

"We'll be careful," Bruce promised. "You sit tight, dad, and by the time you're ready to walk again you'll see us back here with Uncle Quentin, the gold and all. Now I'm going to turn in, for Bleak says we've got to start at sun-up!"

But the sun was not yet up when Bleak, already dressed, roused the two boys.

"I want to be away before light," he said. "Git your clothes on and come right away."

The clearing, the woods, and the lake were bathed in soft moonlight as the three slipped silently down to the water's edge. The canoe was ready, and within a few minutes they were paddling steadily towards the lake's head. The banks closed in, and they found themselves breasting the strong current of the river. Dawn came, then sunrise, and a thin mist rose from the river as the sun blazed down on the dancing stream, but they kept on until a distant thunder of sound warned them that they were approaching a rapid.

"It's the Goose Neck," Bleak told them. "Mighty bad place, but not very long. Arter we've carried our stuff to the head we'll stop and have dinner."

There were six packs in all, so this meant two journeys, and after that they would have to carry the canoe. They shouldered the first three packs and started. The trail was steep and narrow, and the three went slowly, stooping under their loads. Bleak led.

Without warning the ground gave way beneath them. The trail opened at their feet. It was all so sudden they had not even time to cry out before all three had toppled down helplessly into the bottom of a deep pit. Their breath was knocked out of them; their loads fell thudding into the muddy bottom of the great hole. A moment of gasping silence, then Bleak scrambled to his feet.

"A trap!" he cried, as he looked round at the walls which surrounded them. "Say, we don't need to ask which way them thieves went!"

"You—you think they made this to catch us?" panted Bruce, as he clambered up.

Bleak did not answer. He was looking down at Clive who lay unpleasantly still, stretched out on the floor of the pit.

"Clive's hurt!" he said sharply.

BRUCE dropped beside Clive, who was lying face downwards in the mud which covered the bottom of the pit, and lifted his head.

"Hurt, old man?" he asked anxiously.

"N-no," gasped Clive. "Wind knocked out of me. T-that's all. B-but what's happened?"

"Why, we jest walked slap into a trap as them thieves set fer us," replied Bleak. "Only they didn't reckon as there'd be more than one feller on the trail," he added, with a grim chuckle.

"That's funny," said Bruce sharply.

"Why do you say that?" asked Clive.

Bruce went rather red. He was thinking of what his father had said about Clive's father being the thief. Although he had so stoutly denied his belief in anything of the kind, it was a tremendous relief to get proof like this that there really was a gang, for it must have taken several men some time to dig this pitfall.

"Well, it is funny," he said lamely. "I don't see why they should think only one man would be following."

"It would have been mighty awkward fer that one man," said Bleak, "for I don't reckon he'd ever hev got out o' this here pit by hisself. But, being as there's three on us, we didn't ought to hev much trouble. You climb on my shoulders, Bruce, and spring up. You ought to be able to catch hold. Then you can let a rope down, and we'll soon be out. But take off your boots first."

Bruce did as he was bid, and Bleak, leaning against the wall, hoisted him as high as he could. Bruce jumped and caught the edge, but the loose stuff broke away, and he dropped back.

"Try the other side," said Clive. "There's stone there."

The second attempt was successful. Bruce lugged himself up; then he helped Clive out, and between them they pulled up Bleak. Bleak looked back into the pit.

"We come out of that mighty well, boys. After this I guess we keep our eyes skinned. Likely them skunks hev set out a few more little surprises fer us along the road."

"Then it's plain they thought some one would be after them," said Bruce.

"I reckon so," agreed Bleak.

"Yes, but who were they afraid of?" questioned Bruce. "If they had Uncle Quen with them I don't see who they thought was coming after them. They must have known dad was laid up."

"I'll allow it's funny," said Bleak. "Anyway, they wasn't taking no chances," he added, with a grin. "But we'll hev time to talk it over while we eat. Let's get the stuff to the head of the rapids and have dinner."

After dinner the boys were glad to rest, but Bleak went prowling about, examining the ground.

"There ain't a lot of sign left," he grumbled, when he came back. "The rain's washed out most of it. But there was three on 'em. I'm sure of that much, and one's a big feller. I reckon he weighs all of two hundred pound. And it looks to me like another man has passed since they three went on."

"Another man," said Bruce. "Then why didn't he fall into the pit trap?"

"Now you're asking something as I can't tell you; he may hev spotted it," replied Bleak. "But I'm willing to gamble there was two canoes."

Clive looked interested. "Perhaps my dad wasn't taken away by them. Perhaps he followed them."

Bleak shook his head. "If he'd been going to do that he would surely have let Mr. Lyndall know."

"Or left a note," added Bruce.

"Yes, I suppose so," agreed Clive unhappily. "The only thing is to catch them as soon as possible."

"That's good sense, son," said Bleak. "Ef you're rested, let's be moving."

They moved. They kept on moving. Two paddled, the third relieving at regular intervals, and the pace they travelled was surprising. But the boys learned more than merely how to drive a canoe, for wherever they landed or when they made a portage Bleak had their noses to the ground, hunting sign. He showed them how one track differs from another, how to tell when a man is carrying a load by the way his heels sink in soft ground, and by the length of the steps. He pointed out good camping grounds. He showed them how to make a fire when the woods are sopping wet with rain and how to build a brush shelter against the wind. He instructed them in the art of tagging or towing a canoe up a rapid without damaging it. There was much more than this, for he pointed out the trails of various animals, bear, wolf, moose, carcajou, beaver, and many other denizens of the great northern forest, and showed them how to trail these creatures. He gave them lessons in shooting. Luckily they had both been well grounded in this in their school rifle corps, and Clive rapidly became a really good shot. Another important lesson was how to catch fish.

"The bacon we got along with us ain't going to last very long, and we got to live on the country. There's plenty to eat in the woods if you knows how to find it, birds, squirrels, rabbits, and fish. Give me a knife and some string and a few fish-hooks, and even if I didn't have no gun I reckon I wouldn't starve."

"What would you do—make a bow and arrows?" asked Clive.

Bleak laughed. "I might if I had to kill a deer, but traps pays best. I'm a-going to show you boys a heap o' snares and traps afore I'm finished with training you."

As they pushed up the river it grew narrower and more swift. Rapids became more frequent, and it was real hard work portaging the packs and canoe up the steep bush trails. On the fourth morning they came to something that was not a rapid but a fall where the whole river came thundering down over a thirty-foot ledge of limestone. They drove the canoe into the right-hand bank, landed, and began to unload. By this time the boys knew their job so well there was no need for orders. Clive shouldered his load and started; then all of a sudden he stopped, dropped it, and turned to Bleak.

"No sign," he said.

Bleak went forward and examined the ground. When he turned there was a light of real admiration in his eyes.

"You can sure use your eyes, Clive. You're plumb right. They ain't been this way at all."

Clive flushed a little at the praise, but before he could ask any questions Bleak went on:

"They're smarter than I reckoned, but I guess I know just what they've done. They must hev left the river about two mile back and crossed the Height o' Land." He began stowing the packs back into the canoe. "In you get. Thanks to Clive here, we ain't lost more'n an hour, and I reckon to make that up afore sundown."

BLEAK was right, for when, after backtracking for a couple of miles, they landed again, he was able to show them the familiar tracks going straight up the bank into the woods. Two hundred yards back they came to a camp site with the ashes of a fire. A quantity of splinters and shavings lay around. Bleak pointed to these.

"What do ye make o' that, boys?"

Bruce and Clive started prowling round, but presently Clive began to push on up the hill. Bleak watched him with a faint smile on his weather-beaten face.

"I knowed he'd got brains," he whispered to himself.

Clive came back. He looked eager yet somewhat puzzled.

"Wal?" drawled Bleak. "Got anything ter tell me?"

"Yes," said Clive. "They've made some sort of sledge and dragged the canoe right up the hill. But what they've done that for fairly beats me."

Bleak nodded. "Right every time, Clive. That's jest what they hev done, and they got two reasons. One was to throw us off the trail; the other to git easier travelling inter the north."

Clive laughed. "Hauling a canoe up hill doesn't seem to me the easiest sort of travelling, but I suppose there's a river in the next valley."

"That's it, son. She's the Lizard Creek, and she runs due north. Ef you remember, I spoke of their crossing the Height o' Land. I reckon you Britishers 'ud call it the watershed. It means a bit of real hard work fer half a day, but arter that we're running pretty with the current."

"Then I suppose we'd better make a sledge and do the same," said Clive.

"Precisely," answered Bleak, as he picked up an axe and started on a convenient tree.

It took them about two hours to build a rough sledge on which the canoe and its load were cradled. Then they had dinner and a rest, after which they tailed on to the draw rope and started to haul the sledge up the long slope. The woods lay drowsy in the heat of the August afternoon, and perspiration poured down the faces of the three toilers as they made their slow way upwards. Luckily they had a plain trail to follow, and that saved a deal of time. Even so it was nearly sun-down before they reached the top of the ridge, where they stopped to take breath.

Clive, always eager, walked on a little way through the low- growing trees which covered the crest of the hill. All of a sudden he came running back.

"Bleak," he exclaimed, his eyes shining with excitement, "there's a town just ahead of us."

Bleak's eyes widened. As for Bruce he gazed suspiciously at his cousin.

"The sun's been a bit too much for him," he said, "or else he's pulling our legs."

"Nothing of the sort," snapped Clive. "If you don't believe me come and look."

He started back, and the other two followed. About a hundred paces on, the hill-side broke away in a steep slope which ran down half a mile or a little more to a stream. On the near side of the river was a level space ten or twelve acres in extent, and on it a town. Not much of a town, for there was only one street with perhaps a score of houses on either side. But they were real houses with glass windows reflecting the red light of the setting sun, and there appeared to be a couple of hotels and even a sort of town hall.

For a full minute the three stood gazing at this utterly unexpected sight. Bruce was the first to speak.

"Is it a mirage?" he asked. "Or have I got sunstroke too?"

Bleak laughed. "It's real enough, son. I guess it's one of these here mining settlements, but I ain't never been here before, and I never did know there was any kind of a town anywheres near."

"It's a bit of luck for us," said Bruce. "We can buy some fresh stores, and it wouldn't be a bad idea to have supper to- night at one of those hotels and save cooking."

Clive laughed. "You lazy beggar! You always did bar cooking. Still, it would be a bit of a change to try some one else's cooking." He turned to Bleak. "Would it be safe to leave our stuff up here and go down?"

"So long as we hang our grub packs up in a tree I guess the canoe will be safe enough. I ain't so sure whether we'll be as safe in that there place below."

The quick-witted Clive caught his thought.

"You mean the thieves might be in the town?"

Bleak pursed up his lips. "They might, but if they ain't there's others."

Bruce grinned. "Hotel-keepers? Yes, some of them are thieves, but we can keep our end up, can't we?"

"We'll try mighty hard," said Bleak dryly. "Let's put our grub safe and shift down."

The food packs were slung high enough to be out of reach of what Bleak called varmint—that is wolves and wolverines— and the three went down the hill towards the little town. By this time the sun had set, and the landscape was bathed in the soft yellow light of the afterglow. At some previous time the hill-side had been cleared of trees—probably for timbering the mine and for firewood—but a thick undergrowth had sprung up which covered their approach. Coming nearer, they were struck by the curious silence which brooded over the place. There was no sound of voices or traffic, and no smoke rose from the chimneys.

As they came out of the brush just above the end of the main street Bleak pulled up and gave a queer laugh.

"I reckon we'll hev to do our own cooking to-night same as usual," he said.

"What do you mean?" asked Bruce, puzzled.

"I mean there ain't no one here to do it for us."

Bruce stared, but Clive understood.

"The place is deserted," he said quickly.

"Jest that," agreed Bleak. "She's a dead town."

"That's the rummiest thing I ever heard of," said Bruce.

"Nothing rum about it, son. The west is full on 'em. The mine makes the place; then the lode peters out, and the folk shift out. Sometimes they don't even trouble to take their stuff along."

"Well, let's have a look at it anyhow," said Bruce eagerly.

"Sure, you can look if you wants to," Bleak told him, and the three walked on into the street.

The town was dead. There was no doubt about that. Grass was growing in the street, the paint was peeling from the wooden fronts of the houses, much of the glass was dropping from the rotting window-frames. They went into the first house they came to. It had been a store of some sort, for there was a counter, and the wall behind was lined with shelves. These, the counter and the floor, were thick with dust. Some barrels stood against the far wall, but they were empty. A stove red with rust was in the centre. The whole place had a most mournful appearance. Clive shivered slightly.

"It's beastly," he said. "I'd hate to spend the night here. I'd feel as if the ghosts of the people who lived here were flitting about."

Bruce laughed. "So long as there was nothing worse than ghosts I shouldn't worry. Let's go and look at the hotel."

"All right," said Clive, "only I'm jolly well going to clear out before it's dark."

As they turned towards the door all of a sudden there was a sharp splintering sound, and the barrels of a shot-gun were poked through the window.

"Put up your hands," came in a queer, quavery voice.

All three raised their hands quickly and stood staring at an old man who was regarding them from behind his gun. He was quite small, had a grey beard and whiskers, and was neatly dressed in funny, old-fashioned clothes. On the lapel of his coat was pinned the silver badge of a marshal or policeman.

"So I got you arter all," he said, with grim satisfaction. "Now march out, keeping your hands raised, and walk before me to the lock-up."

SINCE there was nothing else for it the three obeyed and, keeping their hands up, walked out into the open.

"Now, march," said the old fellow, motioning with his gun for them to go straight up the street.

But Bleak stood still.

"Say, friend, what do you take us for?" he asked.

"Don't you dare call me friend," retorted the other angrily. "The marshal of Sheba ain't friends with a pack o' scallywags like you three."

"Ain't you a bit hasty?" asked Bleak mildly. "I wouldn't call a feller a thief till I knowed he was one."

"I reckon I knows all I want to know about you," growled the other. "And I'm going to learn you that there's still law and order in the town of Sheba, even if there is only one man left to enforce it."

Bruce broke in. "But we haven't done anything to break the law, sir," he said sharply, and his crisp English voice seemed to startle the old man. "We are hunting thieves ourselves—men who stole the gold from the Last Chance mine."

The old fellow came a step nearer and stared at Bruce. It seemed plain that he was somewhat short-sighted.

"You mean to say you ain't the chaps as shot up this place two days ago?" he asked, with a shade of doubt in his tone.

"It's the first time we've ever seen the place or heard of it," Bruce told him. "My cousin here, Clive Winslow, and I are fresh from England. When we arrived at Last Chance we found my father laid up with a broken leg and all the six months' clean-up of gold gone. My uncle, Mr. Winslow, had gone after the thieves. So we asked Mr. Ricard here to come with us, and we've been trying to catch my uncle up and help him to run down the men. We hit their track where they dragged their canoe over the Divide, and that's how we found your town."

Bruce told his story in such a straight-forward way that the suspicions of the old gentleman were distinctly shaken.

"You certainly speaks like a Britisher," he said uncertainly. "And you ain't much more than a kid. But I ain't taking any chances after what happened two days ago. Keep your hands up while I sees if you got any guns in your clothes."

"I got a gun," Bleak told him. "You can take it if you've a mind to. But these here boys ain't armed."

"I told you I wasn't taking any chances," retorted the old chap, and after possessing himself of Bleak's small revolver carefully searched the boys.

Bleak laughed. "Now I hopes you're satisfied," he said. "If you ain't maybe you'd like to look in my wallet where you'll find my licence to shoot game with my name and my address at Tequam."

"You come from Tequam?" exclaimed the other sharply.

"That's my home," said Bleak.

"Do you know a gent, named Skinner as lives there?"

"I'd ought to. Joe Skinner fives next door to me with his wife and his two kids, Mally and Bud."

An extraordinary change came over the old man's face.

"He's my boy," he said eagerly. "I'm Ezra Skinner."

"Well, I'll be shot!" exclaimed Bleak. "I've heard him tell of you. He used to wonder if you was alive or dead. I reckon I can tell him you're a long ways off dead," added Bleak, with a faint chuckle.

"No, I ain't dead yet," agreed Ezra. "All right, boys. Put down your hands. I'm sure glad you're not the folk I thought you were, but ef you'd been through what I went through two days agone you'd be every bit as skeery as me. Those fellers fair tore the town up."

"Who were they?" asked Bruce eagerly. "I don't know as I can tell you much except that there was three of them," replied Ezra, scratching his head.

"One was a big chap," put in Bleak. "Weighed about two hundred pound. And one, I'd say, limps a little."

Ezra's eyes narrowed. "Thought you said you hadn't seen them."

"I've seen their tracks," Bleak answered. "You're right about one being big. And ugly as he's big. And one does limp a little. I'd reckon he'd had a wound in his thigh some time or other, which made the muscles shorter. Anyway, they're three bad fellers, and I'm mighty glad to be shot of them." He paused and looked at the boys. "Come on up to my place and eat. Arter that I'll tell you."

He led the way briskly up the grass-grown street. As they passed the big building he pointed to it.

"That's the Palace Hotel," he said. "Used to do a big trade years ago when the mine was running. I live in that little house up at the end."

Ezra Skinner's little house was neat and tidy except for two or three broken window-panes which he pointed out.

"Them fellers broke 'em," he said angrily. "They shot the whole place up, and it was mighty lucky they didn't shoot me too. Now sit yourselves down while I rustle some grub."

A fire was burning in a small iron stove. Skinner quickly put slices of venison into a frying pan and coffee into a coffee pot. He opened a couple of tins of peaches and one of condensed milk. From a cupboard he took biscuits, that is, small cakes of baking powder bread made by himself, very light and crisp.

"I got plenty of grub," he said, as they sat down to supper. "There's stuff here to last me a lifetime. You see, about eight year ago the diggings on the creek began to git worked out, and then came the news of the big strike over on the Porcupine. Every mother's son packed up and went out. You never saw such a rush. They jest took what they could carry and left the rest."

"But you stayed?" said Bleak.

"I had to stay," said Ezra gravely. "I was marshal of Sheba, and I reckoned it was up to me to stick by the town. Anyway, there's gold here yet, and some day I reckon to strike the mother lode, and then Sheba will be her old self again."

"Pretty lonely, isn't it?" asked Bruce.

Ezra nodded. "That's a fact. Specially in winter when the wolves come down out of the hills. But I got fire and grub and a gun, and I keeps pretty busy. I don't have much to worry me."

"Except when strangers turn up," suggested Clive, with a smile.

"I don't mind strangers if they behaves themselves. It's only folks like those three you're after."

"But what did they want?" asked Bruce.

"Grub. They tried the Palace first and tore the whole place up, looking. When they didn't find none they got mad and shot up the big mirrors and did a lot o' damage. Arter that they come up this way, but I reckon my old scatter gun discouraged 'em. I peppered 'em some and arter a bit they quit."

"You saw only three?" asked Clive.

"Three was enough," said Ezra dryly.

"I'm thinking of my father."

Ezra shook his head. "I didn't see nothing of him, but that ain't to say he didn't come by. I'm off prospecting most days."

"He's passed and gone on," said Bruce to Clive.

Clive looked worried. "What chance will he have against these three blackguards?" he asked, and for once Bruce could not find anything comforting to say.

THEY slept at Ezra's house and early the next morning went up to fetch the canoe. It was easier getting it down hill than up, and in a couple of hours they had launched it in the Lizard. Ezra came down to see them off.

"I reckon you've gained a day on them gold thieves already," he said, "and I'm going to tell you something which will maybe gain you another day. About twelve mile down from here you'll come to the Split Rock Rapids. They ain't very long, but they're steep, and I'll allow they look mighty bad. I guess pretty near every one who uses the river portages round 'em, and a mighty bad portage it is, because you got to carry everything up to the top of a bluff nigh two hundred feet high. But Split Rock ain't near as bad as it looks or sounds. I'll allow it's dangerous when the water's low, but there's plenty of stream coming down right now, and you won't find no difficulty in running 'em. There's only one bad place, and that's jest at the bottom where the big Split Rock stands. When you see that there rock, keep to the right—it's the narrower channel but a sight straighter than the one to the left. You get me, Ricard?"

"You bet, and I'm surely obliged to you, old-timer."

Ezra shook hands all round and stood watching as they pushed off.

"I hope you find your lode," cried Bruce, as he dipped his paddle.

"And you be sure to call in on your way back," Ezra answered.

Then the canoe swept round a bend, and the little lonely old man was lost to sight.

The boys soon found it was a different and much easier business going with the stream than against it. Yet even so they were amazed when, after only two hours' paddling, the river began to narrow between high rock walls and a low thunder came from the distance.

"Surely it can't be Split Rock Rapids already?" exclaimed Bruce.

"That's what it is, boy," said Bleak. "And here's where we make our big gain. Bruce, you git up in the bow with the pole. Clive, you set in the middle, but don't use your paddle onless I tells you. I'm a-going to take her through."

It was the first time the boys had run a rapid, and their breath came a little quicker as the murmur increased to a roar. The speed of the canoe increased, and suddenly they saw ahead of them leaping white breakers which dashed against dark rock masses. Clive gasped, for it did not appear to him to be possible that any craft made by man could pass through that tangle of rocks and roaring waters in safety. The canoe dipped slightly, then shot forward with the speed of a car. Fingers of ice seemed to grip Clive's heart, for before him was a sea of tumbling white water the end of which was hidden in a curtain of mist.

The light craft plunged down the long, smooth, swiftly running stretch that formed the upper part of the rapid. Right ahead a great black rock showed its ugly head above the surface; then, just as the canoe appeared to be about to charge it bow on, Bleak, with one sharp twist of the paddle, wrenched it aside, and the rock swished past like a dark phantom and was lost to sight. Another rock and another were passed in similar fashion. The canoe flew past them at dizzy speed. The roar of the water was deafening; spray dashed in sheets over the canoe and its occupants.

Suddenly the light craft struck a huge wave and seemed to leap bodily into the air; yet Bleak kept her head straight, and she plunged down the far side at an even more frantic pace. It seemed to Clive as if they were dropping over the face of a fall. Two smaller waves, great rolls of water, were passed in similar fashion, and for a moment the mad pace slackened slightly. But only for a moment, for then they came upon another slide where the whole mass of the river, penned in a breadth of barely thirty feet, shot downwards in one great spout. At the end of this spout the stream widened a little and was split by a tall double-headed rock. To the left the channel was broad and seemingly open; that to the right was a mere crack so narrow that it seemed as if there were barely room for the canoe to pass.

"To the right, Clive. Paddle!" Bleak shouted.

Clive's paddle flashed, but all the weight of the stream was carrying them to the left, and for a bad moment it seemed as if their efforts to turn the canoe would be useless. For an instant she was almost broadside to the current, and Bruce raised his pole to fend off from the great rock. But Bleak's strength was tremendous, and at the very last moment success rewarded his efforts. Passing the rock so close that Clive could have touched it with outstretched hand, they switched into the right-hand channel. Once they were in it, the stream did the rest, and it was only necessary for Bleak to steer. The swift current running smoothly bore them along, and in less time than it takes to tell they had shot into safety in a broader, slower reach where no rocks showed above the surface.

Bleak pulled out the old silver watch he always wore fastened to a leather strap which was twisted into a buttonhole of his flannel shirt.

"Jest under three minutes," he said with a faint smile.

"Gosh!" said Bruce. "It felt more like three hours to me. What about you, Clive?"

"I nearly had heart failure," said Clive, yet his grin contradicted his words. "But I say, Bruce, this is fine. We must have picked up miles on those gold thieves. Let's shove ahead and see if we can't catch them."

Here Bleak put his foot down.

"We'll shove ashore, son, and get some grub. No sense in playing ourselves out. We'll paddle a heap better after a good dinner."

Bleak's word was law, so they paddled on until clear of the gorge and landed on a pleasant stretch of sandy beach with a grove of silver-barked birch trees behind it. It looked, Bruce said, as if it was made for camping. They pulled up the canoe, hauled out the grub pack, and got from it cold meat and bread. Plain fare, but they were hungry enough to enjoy it thoroughly.

After eating, Clive got up to have a walk round and stretch his muscles cramped with long hours in the canoe. He had not gone fifty paces before his shout brought the others hurrying after him. They found him pointing to the ashes of a small fire.

"They're warm," he said eagerly. "They're still warm."

Bleak felt them, and for once a little tinge of excitement showed on the leathery face.

"By gum, you're right, Clive! Those fellers ain't been gone more'n two to three hours. I reckon they spent most of yesterday portaging round them three rapids and were that tired they slept late this morning. Anyways, I'll lay they didn't leave afore ten."

"And it's not much after midday yet," said Bruce, glancing at his shadow. "Bleak, if we shove on at once we may run into them before night."

"We'll make a mighty good try at it," declared Bleak, as he started for the canoe.

Clive stopped him. "One moment, Bleak. Are you quite sure this fire was made by the fellows we're after?"

"What do you mean, boy?"

"I was thinking of dad," said Clive.

Bleak came back and made a quick examination of the ground around the fire. The ground was hard and dry, but what he saw seemed to satisfy him.

"No. The big fellow was here. I got his tracks. It's the gold thieves and no one else."

Clive's face fell.

"Then where's my dad?" he asked.

But this was a question to which he got no answer. Two minutes later the three were back in the canoe and driving full speed down the river.

FOUR hours later the canoe was still driving swiftly down the Lizard. Travelling with the current Bleak and the two boys had covered the better part of thirty miles during the afternoon, and now at every bend they checked and looked out cautiously, hoping to get a sight of the thieves whom they were chasing. But still there was no sign of them. Bleak ceased paddling.

"They been making better time than I reckoned," he said, with a puzzled frown. "I wonder if they got any notion that we're close onter them."

"I don't see how they possibly can," said Bruce. "If we haven't seen them how can they have seen us?"

"They don't need to have seed us, boy," Bleak answered. "Jest one puff of smoke arising above the trees would be plenty to warn a chap if he's a woodsman. And, if I'm not mistook, one of them chaps is a breed."

"What's a breed?" asked Bruce.

"A half-breed, part French, part Injun. Some on 'em is bad medicine, but nigh all is good woodsmen."

"But we were at Sheba last night," objected Clive. "So there was no smoke for them to see."

"Aye, but the night before we had a good fire," said Bleak. "And, now I think of it, it's mighty likely that they might have seed the smoke from that."

"Then they'd know we had escaped from their pit trap," suggested Clive.

Bleak nodded. "I ain't sure, but it looks that way to me. If they was just loafing I reckon we'd have seed 'em by now. We've done some tall travelling since dinner."

"It seems to me it's a case for strategy," said Clive.

"Strategy?" repeated Bleak, in a puzzled tone. "I don't get you, boy."

Clive laughed. "I only meant we might try the same sort of dodge. There's a big bluff up there to the left, and the top's quite bare. My notion would be to land and climb up and see if we can get a sight of them, either on the river or on their camping ground."

Bleak glanced at the bluff and turned the canoe inshore.

"Not a bad notion, Clive. You, can try it if you've a mind to. Only be mighty careful you don't show yourself against the sky- line. You better take the glasses."

"I'll be careful," Clive promised, and a minute later was ashore and scrambling up the steep.

It was a tough climb up across shelving ledges thick with heavy brushwood; yet to Clive it was a pleasant change after the long hours of monotonous paddling, and he went rapidly up. When he neared the top he moved more carefully and got down on hands and knees. Before he reached the ridge he was down on his stomach, crawling like a snake. He came to rest behind a loose boulder and raising his head carefully looked around.

From this height, a couple of hundred feet above the river, he could see over a great stretch of country with the river winding in wide curves towards the north. Far in the distance lay a big lake, its waters crimson under the setting sun, but Clive hardly glanced at it; his eyes were scanning the river, scanning it in vain, for he could see nothing moving on its surface. He noticed a short rapid about a mile away and followed the curves of the stream with his eyes, but without noticing any sign of life.

"That's odd," he said to himself. "Surely they can't have got as far as the lake."

Then all of a sudden a little dark object looking no bigger than a beetle crawled into sight around a curve, the high bank of which had so far hidden it, and Clive gave a little gasp as he realised that it was the canoe which they had chased so far and so long. He quickly took the glasses from their case and focused them. Like magic the dot grew into a canoe with three men in it. Though the distance was too great to get their faces plainly, Clive saw at once that one of them was a huge fellow, a great bull of a man, who sat in the stern and paddled with powerful strokes. He was white, and so was a second smaller man who sat amidships, but the third, the one in the bow, was dark skinned with black hair.

"The breed," whispered Clive. "Bleak was jolly well right."

Clive's first impulse was to case the glasses and hurry back downhill with his news, but then it occurred to him that it was very near sunset, and that, if he waited a little, he might see where the gold thieves camped. So he lay still. The canoe vanished behind a curve, to reappear a few minutes later in an open stretch beyond. Clive's glasses showed him a low shingle bar on the left of this stretch, which looked to be an ideal camping ground. And the gold thieves apparently were of the same opinion, for they paddled in and ran their canoe ashore. Clive waited long enough to watch them start unloading, then turned and hurried back down the bluff.

"I've seen them all right," he announced to the others. "They've just camped on a sand bank about two miles away."

Bruce sprang up excitedly.

"Topping! I say we'll get them inside an hour. Get in, Clive, and let's shove along."

A slight laugh from Bleak damped Bruce's ardour.

"What's the matter, Bleak?" he asked.

"How was you reckoning to get them fellers?" questioned the guide, with gentle sarcasm. "Do you reckon they'll come and hold out their hands to be tied or maybe offer to carry the gold home again?"

Bruce got rather red. "I wasn't thinking that, of course. My notion was to surround them and hold them up."

"You'd maybe find that a mite difficult seeing as one on 'em is a breed," said Bleak. "See here, Bruce, I don't want to preach, but catching up with these fellers is one thing and catching 'em another. You can take it they're every one of 'em armed, and mighty likely to shoot if anyone interferes with them. We wants to get your dad's gold back, but we don't want to get killed a-doing it."

Bruce looked half sulky for a moment, but almost at once his face cleared.

"Of course you're right, Bleak, and I'll obey orders. But what are your orders?"

"My notion is this. We goes on a piece, about a mile, say, and stops as close as we can without them seeing us. Then we lies low till one in the morning and arter that paddles very quietly up to their camp. Then we crawls on 'em like Injuns and jumps 'em while they're asleep. Looks to me that's the only way we kin do it without bad trouble."

"I see," said Bruce. "Then do we push on while it's daylight?"

Bleak nodded and dipped his paddle.

THE boys were very silent as they drove the canoe onwards. The prospect of getting to grips with the gold thieves was tremendously exciting, and the more so because of Bleak's words of warning. Clive was thinking, as he paddled, of that huge bulk of a man whom he had seen through the glass, and he realised that such a man might prove a very dangerous adversary. It came to him that, up here in the wilds, there was no one to help them if they got into trouble—that they had to depend entirely on themselves. There was no policeman round the corner, and they three had before them the task of arresting three grown men who would probably fight furiously in defence of their stolen gold.

He glanced at Bruce and saw that he was evidently thinking the same thoughts, but though Bruce's face was grave there was a light of battle in his eyes, for Bruce was a born fighter. Clive noticed for the first time how tremendously his cousin had developed in the past few weeks. He had broadened out, and his muscles had toughened. They rolled like cords in his bare brown arms as he swung his paddle. He looked to be a match for anyone, even a grown man.

The rumble of the rapid made itself heard, and the next minute they came to its head. It was steep, but short and straight, and since the other canoe had passed it none of them expected any difficulty. Another few seconds and the bow dipped, and the canoe went flying down the spout. Bleak kept her dead in the centre, and she shot forward at tremendous speed.

This place was not like the Split Rock Rapids, for there were very few rocks in sight, the only two which showed being close together at the lower end. But the passage between them was plenty wide enough for the canoe and looked to be of ample depth.

It was only a matter of moments before they reached this pass, but as the canoe drove through it there came a slight jar. For an instant the canoe seemed to check and to be on the point of spinning round, but with a powerful stroke Bleak righted her, and again she leaped forward.