RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on an old print (ca. 1800)

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on an old print (ca. 1800)

N the heart of the gloomy coast ranges of Oregon, among the burning foot-hills of New Mexico, in craggy gorges of the mighty Andes, and among the bare granite ranges which fringe the spinifex desert of Central Australia wander the hunters of lost mines.

There are never very many of them, and they are scattered thinly over enormous stretches or territories, but their numbers are fairly constant, for when one dies his precious secret, or well-thumbed plans are bequeathed to a successor, and one more human being plunges into the wilderness, there to continue the endless search. The hardships are terrific. It is amazing how men can be found to endure them willingly. But it is faith that sustains the seekers--faith in the existence of that which they seek, and in the enormous wealth of gold, silver, or precious stones which the lost mine contains.

There is not a mining district in the world, from Alaska to Australia, which has not its tales of lost mines. Ophir, whence David and Solomon drew over twenty-three million pounds' worth of virgin gold, has been lost for more than thirty centuries; the Phantom Mine of Routh County, Colorado, has been sought for less than thirty years.

The region where lost mines are most plentiful is the western part of the United States. All the gold-bearing States, from Oregon in the north to New Mexico in the south, teem with legends of deposits of gold or silver once located but now lost. Though different in detail, there is one point of sameness in most stories of lost mines. In almost every case the prospector, having located one of Nature's treasure-houses and brought back glittering samples to civilisation, was making a second journey out to his bonanza when sudden death overtook him. Indians--Apaches particularly--are responsible for many lost mines; grizzles and panthers for some; avalanche, storm, or flood for others.

For instance, there is the Marryat Mine, which lies upon the eastern edge of California. Marryat was an old prospector who one day rode into the town of Clayton with his saddle bags full of samples of gold ore so rich that they fairly sparkled. Having been assured by an analyst of the wealth of his specimens, Marryat rode away on his rough bronco. Somehow the news leaked out, and two men, Temple and Boyce by name, followed on his trail. They camped next night a mile or two behind him. In the morning they rode on. A shocking sight awaited them. There by the ashes of his camp fire lay Marryat's body, scalped and terribly mutilated. That was 1887. The Marryat Mine has never yet been refound.

The most famous of lost gold-mines is the Pegleg. So much is known of this vanished treasure that it seems incredible that its position is still a mystery. Briefly, here is its story. In the year 1853 a wooden-legged tramp named Smith, on his way from Yuma to Los Angeles, took a short cut across the desert. Not unnaturally he lost himself, and was forced to climb a toilsome hill in order to see if he could get his bearings. The hill was the highest of three which lay all together in a little clump. Arrived at last on its bare, rounded summit, Smith succeeded in finding a landmark, and was just going to descend again when he noticed that the ground was strewn with numbers of small, rounded pebbles of a curious dull bronzy colour. Smith had a little collection of frontier curios, and he picked up a pocketful of the odd pebbles to add to it.

Eventually he reached Los Angeles in safety and placed the pebbles in his collection. Some three years later a friend who was a prospector happened to see these specimens.

He picked one up, weighed it in his hand, scratched it, His eyes gleamed. "Where did you get these?" he asked, in tones that shook with excitement.

Smith stared at him suspiciously, "Why do you ask?"

"They're gold, man--pure gold!" roared the other.

Smith's eyes opened wide. His jaw dropped. "Gold!" he muttered, thickly. "An' there was tons of it!" Then he slipped fainting to the ground.

When he came to he was mad as a March hare. He raved of gold. After weeks of illness he got a little better, and in semi-lucid intervals told various people all he could remember of his marvellous find.

Scores went out and searched high and low. But they found nothing. Some died of thirst and hardships, some came home. But Smith was dead.

Years passed. The Pegleg Mine was almost forgotten, when suddenly San Bernardino was thrown into a state of the maddest excitement by the arrival of a prospector with a bagful of rusty-looking rounded nuggets. He had never heard of the Pegleg, but he told of his discovery of the gold on the top of a rounded hill, the highest of a clump of three. Two men got hold of him, questioned him closely, and before dawn next morning the three had disappeared from the town. Others attempted to trail them, but a sand-storm obliterated their footsteps. They never came back. What became of them no one knows.

But the story of the Pegleg is not yet finished. In the seventies, when the Southern Pacific Railway was pushing its way across the desert, two surveyors picked up an Indian squaw nearly dead with thirst. In her handkerchief were knotted half a dozen of the familiar bronzed nuggets.

They gave the woman water, but not a word would she say about the locality of her find, the value of which she evidently knew full well. In the night she disappeared, went back, no doubt, to her own people, and she has never been seen again. But two nuggets which she left with the railway men were afterwards compared with some of Smith's original find, and that they came from the same source could hardly be doubted.

Since then scores of prospectors have tried to re-locate the Pegleg, but if any have ever succeed they have never come back to tell the tale. Yet that the mine is there in a space no larger than the county of Berkshire, and that it is perhaps, the richest deposit of native gold in the whole world, there can be hardly any doubt. There are no Indians there now and few wild beasts. But neither is there any water. That is, perhaps, the true cause why the Pegleg yet remains a lost mine.

The Phantom Mine, mentioned at the beginning of this article, takes its name from the fact that, while it was found three times between 1880 and 1900, not one of its finders ever lived to return to it a second time. This wonderful gold ledge lies somewhere near a creek amid a tangle of ragged hills, in the north-western corner of Colorado.

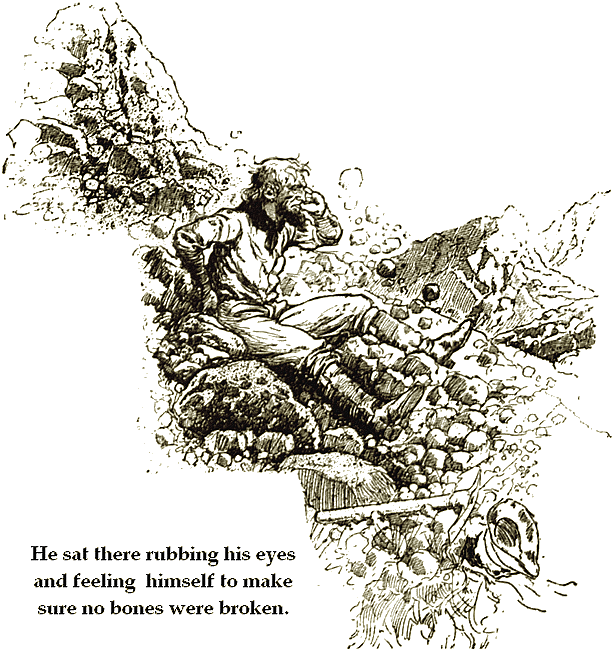

One evening in October 1881, an old prospector named John 08:13 03.02.2022 Boyle was crossing the head of a ravine among these hills when he slipped and went rolling down a steep slope, bringing with him a small avalanche of gravel and earth. He fetched up, half-dazed, on a ledge many feet below, and sat there rubbing his eyes and feeling himself to make sure no bones were broken. Then his glance fell on the rock which he was sitting upon, and he started so violently that he nearly fell the rest of the way. The whole ledge was seamed with streaks and veins of virgin gold. For many minutes Boyle remained there motionless, lost in that maze of happy wonder which comes to a man when chance raises him in a moment from poverty to the command of millions. Never had he seen such a find, never even dreamed of one.

The sun had set before he at last got up and began chipping some specimens from the wonderful ledge. It grew dark rapidly. Boyle had a hard climb before him. He made up his mind to go back to his camp and return in the morning to stake out his claim.

His camp was not more than a mile away. He reached it safely, cooked his supper, and, exhausted with excitement, fell into a heavy sleep. When he awoke next morning six inches of soft snow covered everything, and the thick flakes were still falling. Boyle knew that delay meant death. He would be cut off in the mountains without food. He made straight for Denver, and succeeded in reaching that town in safety.

Next spring, as soon as the snow melted, he was off again. He found his old camping ground without difficulty, but search as he might he could not retrace his way to the golden ravine. All the summer long he toiled, till winter drove him home again. But the disappointment had been too great. Before a second spring came poor Boyle was dead.

Twelve years passed, and Boyle's story had become a camp-fire legend, when a man named Pollock, out on a shooting expedition in the same hills, wounded a wild cat and trailed it to a ledge at the head of a ravine. There the brute turned at bay, and Pollock climbed up and killed it. He was tired and out of breath, and sat down to rest.

Glancing idly at the rock on which he sat, it seemed to him of curious colour. He knocked some pieces of with the heel of his boot and put them into his pocket. Pollock knew nothing whatever about minerals, and it was only by chance that he happened, weeks afterwards, to show his specimens to a friend in Denver. This man declared that the yellow streaks were free gold. Pollock rushed off to an assayer, who at once confirmed the opinion.

Next morning found Pollock on his way back to Routh County. But, like poor Boyle, he could not for the life of him find again the mysterious ledge.

Once more since then has the Phantom Mine been seen by human eyes. Its third finder was what is called a "lunger" an invalid stricken with phthisis, who had come from the East to Colorado in the hope of regaining his health. He was a poor man, but friends in Denver helped him to buy a waggon and sent him out into the hills to prospect. About three weeks later one of these friends received by post from a Routh County village a cigar box full of specimens. They were taken to the assayer who had tested Pollock's find. He declared them to be from the same source--the Phantom Mine.

The friend waited a week or two, then, as no more news came, he started in search of the invalid. He found the man's horse wandering in a valley, with some remnants of harness clinging to it, but the third finder of the Phantom Mine himself had vanished, and no one has ever found out what became of him.

There is seldom any trouble nowadays with the Indians of the United States. They are a degenerate race, who no longer take the war path in search of scalps. In Mexico the case is different, and scores of white men have fallen within the past few years to the rifles of the Yaqui Indians. The Yaqui reservation lies among the spurs of the Sierra Madre Mountains. It is said by those who have visited it that there is no wilder place on earth. Tall, gaunt mountains above, deep, gloomy gorges below, little vegetation and less game, there seems nothing to attract the visitor, even were the place without its human perils.

But, like a rich honeycomb in the midst of a nest of stinging bees, Nature has planted in these wild mountains gold veins of amazing richness, and the legend is that centuries ago the Aztecs worked a great mine in the heart of these hills and got from it masses of almost virgin gold. This mine, they say, still exists. One thing is certain--that the Indians themselves when not on the war-path are always ready to purchase rifles, cartridges, and whisky from the whites, paying for the same in coarse gold and nuggets. This lost mine is said to lie in a gorge about two hundred miles west of the town of Ortiz. Mr Alfred Thomas, an American from Kentucky, actually reached this gorge in the year 1897, and found a well-marked trail leading up to it. He pushed on, only to find the ravine barred by a monstrous hedge of thorny briers, and, as he and his friends tried to hack their way through, suddenly Indians appeared on the heights on either side, and the white men were forced to fly for their lives.

The most famous of lost Mexican mines is the Taiopa, supposed to be located in the Sahparipa district of the province of Sonora. This mine is said to have been worked by the Spaniards, but its position is now known only to a small tribe of Pima Indians, who absolutely refuse to betray the secret.

Yet there it one white person alive who has set eyes on the famous Taiopa. In the year 1898 an old Pima chief fell ill while at a valley farm, and was nursed back to health by a Mexican lady. He went home, and soon afterwards sent his nurse a gift of a lump of gold ore, which assayed something like a thousand ounces to the ton. The Mexican lady, convinced that the ore came from Taiopa, went to the chief and asked him to show her the lost mine. Eventually he agreed, and gave her into the hands of two Indian women for them to lead her to the spot. The women seemed in great fright and would only travel by night. After four nights' hard riding they came to a deep canyon half blocked by a monstrous spur of rock. In the dim moonlight a tunnel was seen leading into the heart of the mountain, and below it a great ore dump.

In the dim moonlight a tunnel was seen

leading into the heart of the mountain.

The visitor gathered samples of the ore, but the Indian women, declaring that they would he killed if they delayed, hurried her away again, and, travelling hard all the rest of the night, took her home by a circuitous route which completely baffled the visitor to recall. Yet she made the attempt. Accompanied by her son, a boy of fifteen, and taking three burros, or donkeys, she started in the following September in search of the elusive Taiopa. Heavy rain came on; in crossing a flooded torrent two burros were drowned, and the plucky woman was forced to return home. The Taiopa remains a lost mine.

One of the weirdest stories of a lost gold-strike comes from the far Arctic. Late one September, about forty years ago, an old whaler, Captain de Boise by name, was working his ship south amid rapidly-forming pack-ice when, through stress of weather, he was forced to anchor in a tiny bay somewhere near Cape Belcher, on the northern coast of Alaska. Two of the sailors took a boat and went ashore. Imagine their amazement when they found the sandy beach literally covered in places with patches of coarse gold and small nuggets which sparkled in the pale Arctic sunlight. But they had hardly begun to fill their pockets when a gun was fired to recall them. The pack-ice was coming in in a solid raft, and the ship had to move at once or risk being ice-bound for the whole winter.

They reached San Francisco in safety, and Captain de Boise endeavoured to get capitalists to back him to send a ship north the following summer. But most people looked upon the story as a sailor's yarn and poor de Boise, disappointed and discouraged, fell ill. He went to San Diego for his health and died there in the Bay View Hotel. During his last illnes he told his story to a newspaper reporter, and it was published not only in San Francisco, but in the East. The two sailors who found the gold were traced, and an expedition arranged. They found what the sailors declared to be the same cove, but, alas, all altered now! A great storm, or, perhaps, a great pack of shore-ice had carried away all the sand. Traces of gold there were, but nothing of the virgin wealth originally seen.

But some say that the real cove never was discovered, and since the opening of the great shore-diggings at Cape Nome many a vessel has spent the summer cruising along that barren coast seeking for de Boise's gold-strewn beach.

Chile has her lost mines, so have Bolivia, Ecuador, and all the Central American republics. It was the story of the gold which lay there that led Pizarro to Peru. We all know how Atahualpa ransomed himself with a roomful of gold, an amount equal to three and a half millions sterling, and how the Inca King was treacherously killed on August 29, 1533. The mines from which came this enormous treasure were lost. They have never been found again, though they have been sought diligently for three centuries and more. Yet of their existence there can be no doubt. No mine that has since been discovered, not even the Potosi of Bolivia, could have produced the precious metal in such lavish abundance as the Incas possessed it. Somewhere in the vast recesses of the lonely Andes those treasure-caverns exist, and one day some lucky prospector will stumble upon them and become rich beyond man's wildest dreams.

It must not be imagined that all lost mines are legends. Only six years ago a long-lost El Dorado was rediscovered. Its name is the "Wonderful" Silver Mine, and it may be seen by anyone who cares to travel to the spot, in the Slocan district of Southern British Columbia, just across the United States border. Its owner and worker is, or was, a few years ago, Mr. W.W. Warner. More than thirty years ago Warner was mining in Idaho, and a dying fellow-miner, to whom he had been kind, told him of a mother lode of enormous richness in the mountains to the north. Loose silver washed from it was to be found at the base of the mountain. Warner located and leased the mountain in which the lost ledge was said to exist.

In the gravel at the bottom he found plenty of loose silver, and he and his men washed out several thousand pounds' worth in the first two years. But, instead of satisfying him, this only made Warner the more eager to find the mother lode. The placer ground creased to yield, the sluice-boxes rotted but Warner would not give up. He built a cabin and spent all day and every day prospecting.

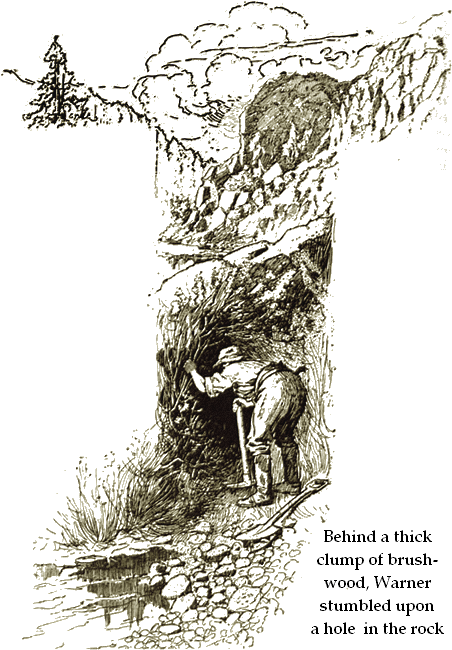

Nearly thirty years passed, and then one day, behind a thick clump of brushwood, Warner stumbled upon a hole in the rock evidently cut by human hands. It was choked with débris, but he soon cleared it. A few hours' work with pick and shovel. and there was the lode for which he had been searching for half a lifetime.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.