RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

THREE people sat together in the small, neat cabin of the stout little salvage steamer Camel. They were David Tremayne, her captain and owner, a fine type of Cornish seaman, his younger brother, Bob Tremayne, while the third was a grizzled, hard-bitten salt of middle age. His face was lined and grave. He looked as though his life had been none too easy a one.

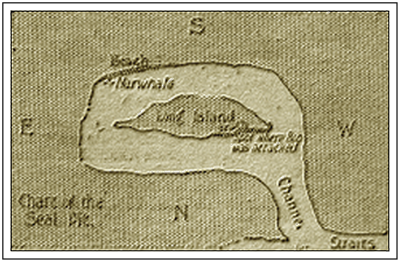

Before him, on the cabin table was a sheet of paper, and on it he had drawn a rough chart.

"Aye, it's a rum place," he said, "and there isn't many as have ever been in there. There ain't nothing to take anyone there except the seals, and 'twas nosing around after them as led me into it.

"Ugh!" he shivered. "I wish I'd never seen it."

David Tremayne took the chart and examined it.

"Yes," he said, "it is a curiously shaped bay. It reminds me of the head of a big snake."

John Harter, the old skipper, lifted his gnarled hand.

"Don't say that," he exclaimed, and there was fear in his pale blue eyes.

The other two stared at him. They were naturally puzzled.

"See here," said Captain Harter, recovering himself. "I ain't going to let you folk go in there without knowing. It wouldn't be fair like. I'll tell you the whole thing, and then you can take the job or not, as you've a mind to."

He drew a long breath, and went on.

"As I told you, we went in there after seal. There's a beach under the cliffs on the south side of the bay and seal lies there in plenty. We got a matter of forty the first day, but the second it came on foggy. Still it wasn't anything to stop work, and I sent the men ashore early in two boats. I stayed aboard myself. The Narwhale weren't lying very far from the shore, and I could hear the chaps working after the seals among the rocks.

"I should tell you that it was a dead calm day, and in that there pond the water was like glass. You can judge my surprise then, when all of a sudden I felt the ship lift like a big wave had took her. I was on deck in two jumps, and sure enough there was a swell sweeping by like an ocean liner was passing at full speed.

"Well, I knowed as well as you know there couldn't be no ship in that inlet, and anyway, we couldn't hear nothing. There was four of us left in the ship and we all stood quiet, listening till our ears ached.

"Suddenly one of them—it was Jake Atkins, the cook—let out a yell like a steam whistle and pointed. There right over the starboard bow was something sticking up out of the sea that looked like a factory chimney. 'Twas too foggy to see it plain, but as I'm a living man, it was something alive."

He paused again. Sweat drops stood out on his forehead. There was no doubt whatever but that he believed every word that he had said. The two Tremaynes listened in silence.

"It hung there for may be half a minute—it seemed like half an hour. Then down it sank, and a moment later the ship was swinging to a fresh wave."

"I lost my head. I don't mind saying it. I've been hove-to three days off the Horn, expecting every hour to be our last, but I wasn't half so scared that time as I was when I saw that awful thing hanging up there in the fog above us. My one notion was to get away. We slipped our cable, started up the motor engine, and ran in towards the shore to pick our other chaps up."

"Next thing we knowed we'd hit a reef, and there we were hard and fast."

Once more he stopped and wiped the sweat from his face.

"What happened then?" asked young Bob Tremayne.

"We provisioned the boats and cleared as fast as we knew how. I'm fond o' my ship as any man, but no money would have paid me to stay in that place for another day. Now I've told you the whole story, and if, after hearing it, you say you won't take the job, I'll be the last to blame you."

There was silence for a moment or two. Then David Tremayne spoke quietly.

"There are queer beasts in these little known waters around the Straits of Magellan," he said. "I should be the last to deny it. Still, with a stout craft like this, I should not be afraid of anything of the kind. I will take the job, Captain Harter, and, if we can come to terms, will do my best to salve the Narwhale."

Harter drew a long breath. "You're a brave man, Captain Tremayne, and I wish you all luck. No one will be more pleased than me to see my old craft again. But this I'll tell you. If I was you, I'd take a gun along. A cannon I mean. There's nothing else fit to tackle the thing I saw, and that's the living truth."

"I'll see what I can get hold of in that way," replied David Tremayne quietly. "Still the creature did not actually attack you, and perhaps we shall be equally as fortunate."

"THERE'S the mouth of the channel," said young Robert Tremayne as he pointed to a break in the cliffs on the southern side of the Straits.

His brother, with whom Bob was standing on the bridge of the stout little Camel, looked in the direction in which Bob was pointing. Then he took from his pocket the small chart drawn by Captain Harter.

"That's it, Bob. And as the tide is just beginning to run we ought to get up without any trouble."

"Wonder if the sea serpent is at home," said Bob with a laugh.

David did not smile, and Bob looked at him in surprise.

"You don't mean to say you believe in the thing, David?"

"I'm older than you, Bob, and not so sceptical," David answered quietly. "And I believe that there are many creatures in the sea which are not yet catalogued by naturalists. And you might remember that these waters are almost unexplored."

Bob stared. "Then you think there really might be a sea serpent?"

"I don't know about a sea serpent. But it wasn't many years ago that the hide of a mylodon, that is a giant sloth, was found in a cave not far from here. Yet naturalists said the big sloth had been extinct for tens of thousands of years. We have the fossilised skeletons of huge fish-lizards in our museums. Why should not some of them have survived? There's plenty of room for them in waters like these."

Bob whistled softly. "Then you believe that old Harter really did see something?"

"I certainly do. He's not the sort to have made imagination. But I don't say it was a sea serpent. It might have been a big whale. Whales play odd tricks at times when they are broaching. I've seen a seventy foot sperm jump out of the sea water like a trout at a fly.

"That's what he saw. That's it, of course," answered Bob.

And then the Camel was headed for the opening, and David had to give all his attention to navigating his ship through the narrow place.

It was a weird and desolate spot. Black cliffs towered on either side and cast heavy shadows across the enormously deep water which lay beneath. The pale Antarctic sun could not cast a ray into the gloomy passageway.

But the passage was of no great length, and soon the Camel emerged from the dark fiord into a wide-spreading expanse of water. It was, as Harter had said, a most curious shape, being almost a perfect oval seven or eight miles long, while the centre was occupied by a long narrow island. The Seal Pit, as Harter had called it, was surrounded by cliffs which in most places ran sheer down into the unfathomable depths of the lough. The island, too, was all bare rock, but at the rear—that is the western end—the cliffs were fringed by a narrow stony beach.

"Let me see," said David, "the wreck is down at the south-eastern end of the place. We shan't sight it until we have rounded the island."

With her powerful engines pumping steadily, the sturdy Camel drove onwards across the dark surface of the water. Looking down into it over the rail, it seemed almost black and gave Bob the impression that it must be of terrific depth.

As they skirted the western point of the island Bob stared at the beach below its cliffs.

"David," he said, "those rocks are simply stiff with oysters, we must have some of 'em."

"All in good time," replied David indulgently. "First, we must find the wreck, and see where we can anchor."

As the Camel turned her blunt nose to the south the wrecked Narwhale came at once into view. There she lay, cocked drunkenly on a reef, quite close to the shore. At this point the cliffs were low and broken, and there was quite a wide beach. David picked up his glasses and focused them.

"Not so bad," he said in a tone of some relief. "If she is not badly holed we ought to have her off without much trouble."

"Is it 'no cure no pay' David?" asked Bob.

David smiled. "That's it lad. Two hundred pounds if we bring her safe back to Punta Arena. And it looks good to me."

The evening was fine and clear. They found good anchorage close to the stranded ship, and presently David was in his dinghy, pulling across to the wreck.

He was aboard about half an hour, and when he returned Bob saw by his face that all was well.

"There's one small piece of rock through her side close up to the bows," he said. "That's all that's holding her. For the rest, she's sound as a bell. We ought to have her off her perch in a couple of days."

"Topping!" declared Bob. "If we go on like this you'll be able to buy back the old place in a year or two, David."

David sighed. "I hope so, Bob," he said. "I hope so. But not in two years. I shall be satisfied if I can do it in ten. There are risks, Bob, remember. And not the least of them is that unpleasant person, Pedro Juarez."

Bob looked a little grave. "Yes he is a brute," he admitted. "Still, we've done him down pretty thoroughly both times we've run against him."

"All the more reason that he will try for another chance," replied David. "So don't count your chickens before they are hatched."

BOB TREMAYNE threw his dinghy into the wind, lowered the sail, got out the oars, and set to pull around the western point of the long island which lay all down the centre of the lough.

It was the next day after their arrival, and he had obtained leave from his brother to go in search of some of the oysters which he had noticed, in passing, on the island beach.

"It's a rum-looking place," said Bob to himself. "Criminy! but I might be the only person on earth by the look of it."

Certainly the loneliness was intense. There was not even a sea bird visible, and the silence was equally complete. But Bob Tremayne was not troubled with an imagination, and he was keen about oysters. He pulled quickly ashore, beached the boat, and fastened her securely, then taking a bag began scrambling among the rocks.

The tide was right out, and along low water mark oysters were plentiful. They were great chaps, four times the size of an ordinary English native. Bob licked his lips. Oyster stew was a dish he was very fond of, and the cook, old Durrit, made it splendidly. Supper that night was going to be a meal worth eating.

The bag was half full, and Bob, with his back to the sea, was prising a specially fine specimen off a rock when, quite suddenly, a wave washed up hissing around him, rising nearly to his knees.

He jumped as if he had been shot. Remember it was almost dead calm and there was not enough wind to raise a two-inch ripple in this land-locked place. Yet the wave that was even now sobbing among the boulders of the rocky beach was at least a foot high.

Bob stared out at the water. It was quite misty now, and he could not see very far. But this he could see—a snowy white foam ring expanding on the surface of the deep, dark water and smooth swells coursing out all around it. It was as though a great rock had been dropped suddenly into the water, yet without making any sound.

Bob's heart was thumping with excitement. It must be a whale. He felt sure that it was a whale. Would it come up again? He waited breathlessly.

It did. A moment later the water broke again, and this time nearer to the shore, and from the centre of the broken surface shot up—no whale, but a something so amazing, so terrible that Bob was literally unable to believe his eyes.

It was a head that had appeared out of the depths; a head resembling that of a snake, but of a size beyond all belief. It was as large as a three hundred pound sugar barrel. Up it shot, swaying horribly. Behind it rose a body as dreadful and incredible as the head itself, a thick, snake-like body, covered with dark scales and coated with barnacles like an old bull whale.

Up and up it went. Would it never stop? It towered, just as Harter had said, like a factory chimney, while Bob, absolutely frozen with terror, stood gaping at the gigantic horror.

At last it stopped, and as it did so, something seemed to snap inside the boy's head, the paralysis left him, and spinning round he shot up the beach like a scared rabbit. Instinctively, he felt that the thing had seen him, and he went from rock to rock in great flying leaps until, reaching the base of the cliff, he hurled himself into a narrow space between two great jagged rocks and dropped panting to the cold, damp shingle below.

There he lay flat on his face, and it is no discredit to him to say that he was almost sobbing with sheer fright. Bob had faced savage animals and men no less savage without his heart missing a beat, but about this thing there was something so abominable, so horridly unnatural, that it took the pluck out of him as a strong hand squeezes water from a sponge.

It was a long time before he could force himself to move, but at last he got control of his muscles, turned round, and looked up at the opening through which he had leaped.

Then every muscle stiffened rigid as stone, his heart seemed to stop beating and abject, awful terror gripped at his very vitals. For there, right across the gap lay the head of the fearful sea beast.

Nothing more repulsive could have been conceived in the wildest dream than that head. It was of a horrible, vivid hue, like that of a long drowned body. The mouth, gaping a yard wide, showed teeth like those of a gar-fish, long and pointed, while from each side of it hung long tentacles of a purplish hue. But the eyes—the eyes were the worst of it. Each as large as a dinner plate, they were as completely void of expression as those of the monster cuttlefish of the great deep.

For many moments Bob crouched upon the floor of his narrow refuge, so paralysed that he could not move a finger. There was only one thought in his mind, a dull gratitude that the opening of his prison was too narrow for that monstrous head to pass through and reach him. Slowly the power to reason came back to him and he began to wonder as to his chances of escape. The beast was hungry, the beast meant to devour him. Of that there was no doubt whatever.

Still he was safe for the moment, and so it would become a contest of patience. He lay very still, hoping the monster would tire and move away. But the creature showed no intention of doing anything of the sort, it lay like a vast log, with its terrible unwinking eyes fastened on Bob.

Bob's patience ebbed away. He grew angry. He stooped, picked up a large stone and flung it with all his force at the huge head. The rook rebounded as from a wall. The serpent never stirred. A thrill of horror sent a chill to Bob's heart as he realised that the brute felt it no more than a fly lighting upon its scales. He must wait—wait till help came. David would miss him at last.

His feet felt very cold and damp. He glanced down. A film of water half an inch deep covered the floor of his refuge. His heart thumped as he suddenly remembered the tide. He glanced at the rock behind him. It was all weeds and shells. The tide then must rise high above his head. If help did not come he would drown.

AN hour had passed. The water was nearly up to Bob's shoulders, The deathly chill of it bit into his bones. Another ten or fifteen minutes at most would see the end. A sound came to his ears through the stillness. It was a low thudding. A ship's engine!

A dark object loomed up. The fog lifted again, and Bob's hopes dropped again to zero. It was a ship, indeed, but not the Camel. This was a large schooner with auxiliary motor, and one glance was sufficient to show him that she was El Capitan, the ill-omened craft owned and commanded by that black-hearted scoundrel, Pedro Juarez! So far from coming to his help, Bob had no doubt but that this pirate was on the track of the Camel. Juarez had vowed vengeance against the Tremaynes, and as he carried a couple of guns aboard his schooner, the chances were ill for the Camel if he could catch her unprepared.

And that, it seemed, was what he now succeeded in doing. Anchored as the Camel would be and with some of her men aboard the wreck, there was little hope for her.

The schooner came straight towards the western point of the island. Soon she way close enough for Bob to see the figures on the deck. Yet they did not seem to see the snake. Probably that was because most of its body was under water, and its head was just the colour of the rocks.

Suddenly a shout came pealing through the still air. They had seen it. Yet, no, for the schooner came straight on. A moment later and Bob knew. They had seen his boat. They took it he was hiding.

The schooner's pace increased. She came rapidly up. She stopped, lay to, and Bob saw a boat lowered.

The boat approached briskly. She was within fifty yards of the beach, when the steersman seemed to notice something out of the common. Next moment he gave a yell, and tugged at his tiller so that the boat swung round within her own length.

But the sea serpent did not move, and now the creeping tide was up to Bob's chin. He knew that he must die, yet swore it should be by drowning and not within the jaws of the monster.

The men in the boat were pulling for dear life. They splashed violently. Perhaps it was this that attracted the serpent's attention. All of a sudden his head rose.

Bob, hardly able to believe his eyes, saw the great column of neck swing upwards.

Came a sudden thunderous crash which boomed in great echoes across the desolate loch. Followed a roar as if ten thousand devils had been turned loose. A great surge of water washed over Bob's head. He was flung about like a cork. Blinded and deafened by the cyclone-like clamour that raged around him, he felt himself suddenly hurled clear of the cliffs, and found himself fighting for life in foaming, tumbling waves.

His outstretched arms grasped something solid, and as the spray cleared from his eyes, he found himself clinging to an upright slab of rock, facing the water, and gazing at such a scene as perhaps no human eyes ever looked upon before.

The serpent, mortally wounded by an explosive shell from one of the four inch guns of the schooner, was thrashing out its life on the surface of the loch.

Bob could not take his eyes off the fearful scene. It was not until at last the frightful struggles ceased and the horror sank slowly out of sight that he was able to give a thought to the other danger—that of the black pirate who meant to destroy them.

He looked towards her. She was in the act of vanishing into the channel leading out into the Straits. There was panic in every line of her.

Bob shook his fist feebly after her, and walked stiffly down to where his boat still rode safely at the end of the long rope by which he had tied her.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.