RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

"The Quests of Paul Beck,"

with "Driven Home"

M. McDonnell Bodkin

Irish barrister and author of detective and mystery stories Bodkin was appointed a judge in County Clare and also served as a Nationalist member of Parliament. His native country and years in the courtroom are recalled in the autobiographical Recollections of an Irish Judge (1914).

Bodkin's witty stories, collected in Dora Myrl, the Lady Detective (1900) and Paul Beck, the Rule of Thumb Detective (1898), have been unjustly neglected.

Beck, his first detective (when he first appeared in print in Pearson's Magazine in 1897, he was named "Alfred Juggins"), claims to be not very bright, saying, "I just go by the rule of thumb, and muddle and puzzle out my cases as best I can."

...In The Capture of Paul Beck (1909) he and Dora begin on opposite sides in a case, but in the end they are married. They have a son who solves a crime at his university in Young Beck, a Chip Off the Old Block (1911).

Other Bodkin books are The Quests of Paul Beck (1908), Pigeon Blood Rubies (1915), and Guilty or Not Guilty? (1929).

— Encyclopedia of Mystery and Detection, Steinbrunner & Penzler, 1976.

"IT was his luck," so Mr Beck always said. "The whole thing might have happened to any man." But no person who had heard the story quite agreed with him.

It was luck, of course, that he found the silver spoon in the hansom cab. Prying about keenly, as was his wont, he saw the thin white edge shining behind one of the cushions and fished out a curious-looking teaspoon and put it in his pocket.

He had a good look at the number of the hansom and the driver when he got out. The hansom was one of the neatest in London, with a sweet little twelve-mile-an-hour mare between the shafts. The driver was a stoutly-built, jaunty fellow, with mottled face and big red nose. He was smartly dressed, with a nosegay in his button-hole and cigar between his teeth.

Mr Beck dismissed his cab and walked to Mr Ophir, the famous jeweller and silversmith, whose name was on the spoon.

He was received by Mr Ophir himself—a mark of special distinction—in the little glass pavilion in the centre of the glittering warehouse.

Yes, Mr Ophir knew the spoon very well. It was one of a set made by his house in imitation of the old apostle pattern. Very creditable imitation; he should say it would need a skilled eye to tell the difference.

"Who got them?" asked Mr Beck, going straight to the point.

"Who got them! Let me see; just one moment. It is in the books, of course, but I ought to be able——" He tapped his forehead, that was smooth and round and polished as an ostrich egg. "Oh, yes, of course, they were part of a tea-set made as a wedding present for the Merediths. Now I remember, they were stolen about a month ago."

"The suburban burglaries," interrupted Mr Beck, and he slapped his big thigh excitedly with his broad palm—an unusual lapse on the part of the most stolid of men.

But his excitement was surely pardonable.

THE London police had for the last few months been startled,

amazed, bewildered by a rapid series of brilliant burglaries, all

within a fifteen to twenty-mile radius of London.

"The cribs had been cracked" in the highest style of art, and the artists with their rich booty had vanished into space, leaving as little trail as a fish through the water. They were gentlemen who did not stick at trifles. Three times, it would appear, they had been interrupted at their work, and three people had been left for dead behind them, and one—a woman—had died.

No wonder then that Mr Beck was excited for a moment at the hope that his "luck" had put him on the track of the suburban burglaries at last. But his excitement was quenched instantly like a spark fallen in water. It was the good-humoured, easygoing, imperturbable Mr Beck who walked home to his cosy lodgings to puzzle his plan out.

He plunged into a great easy-chair, with a pipe stem between his teeth and the spoon before him on the table, as a saint sets a skull to concentrate his meditations. It would be worse than useless, he determined, to arrest or even question the driver. If he knew anything he wouldn't tell it, and plainly he could not be responsible for a silver spoon dropped behind the cushion of his hansom.

If the man were guilty—and Mr Beck fondly hoped he was guilty—a hint of suspicion would ruin all. So Mr Beck sat and smoked and thought, and as the smoke grew denser his thoughts cleared.

"If I could only get quietly inside that fellow's skin," he thought, and with the thought came his plan of campaign. Then he put by the little silver spoon and smoked his pipe out in vacuous enjoyment.

THE result of his meditations was that Mr Beck—this time

a simple-looking farmer up for the cattle show—had a drive

in the same hansom next day and found the cab neater and the mare

faster than he imagined.

He got in talk with the driver, whose name he discovered was Jim Blunt. The Cockney cabby made game of the simple-minded yokel. They had several drinks together, and Mr Beck noted that the spirited little mare was trained to stand quietly as a lamb when the driver was away.

Next day Mr Beck was a portly clergyman on a shopping expedition. He took Mr Blunt's hansom here, there and everywhere, and acquired a multitude of parcels. A most genial and cheerful clergyman was Mr Beck and most affable with his driver, with whom he talked a good deal and whom he talked into the best of good humour. That was at first.

Towards evening the zealous clergyman broached the Temperance question with a distinct personal application, and Mr Blunt got sullen. In parting, the Rev. Mr Beck presented his driver with his exact legal fare, and Mr Blunt was furious. He spoke his views fully and freely, and the other looked and listened, sorting up every trick of face and voice in his retentive memory. Then when a policeman loomed in sight at last the meek Mr Beck turned away with a Christian benediction and meditatively mounted the steps of his lodgings. He had seen and heard enough of his model.

For two days after this Mr Beck was a shop messenger in uniform, with a light tricycle parcel cart, quite empty; and wherever Mr Blunt drove his hansom the tricycle cart unobtrusively followed, faithful as the little lamb to Mary in the nursery rhyme.

In this way the patient Mr Beck found out many things. He found that Mr Blunt was not keen on fares and was keen on sport and drink. He spent his leisure moments—often all day—in the sanctum of a certain sporting public-house in the East End called the "Ram's Horn." There he met a convivial commercial traveller named Fulham and a bookmaker named Grimes, and the three drank and played cards, while a tricycle cart with a heavy, stupid-looking rider went past the door occasionally.

THERE was another change; a startling one this time.

Mr Paul Beck became Mr James Blunt. In clothes and figure and face and voice, in all his tricks and ways, the counterfeit was perfect. Mr Blunt's wife or mother could not have found a difference.

The translated Mr Beck took to dropping into the "Ram's Horn" on his own account at odd times when he had reason to believe Mr Blunt was elsewhere with a fare. He was made free of the sanctum, and the unsophisticated commercial traveller Fulham and the genial bookmaker Grimes received him as "Jim" with rough but unsuspecting cordiality.

They were both big, strong men, active and sleek, who spent money freely. They were full of sly, chuckling jokes about "business" when the three were drinking together. A very little time was needed to convince Mr Beck by a hundred trivial hints that he was on the straight track of the suburban burglars. A dozen times in an hour he seemed on the point of surprising some definite proof. But lead the talk as cunningly as he might he could get no further. For the others assumed he knew as much as themselves, and he dared not appear too curious.

It was a dangerous game. An indiscreet question might arouse suspicion, and suspicion meant death. Besides, it was a ticklish thing playing Box and Cox with the real Mr Blunt, who had a knack of throwing up his engagements and turning up at unexpected times. Twice Mr Beck had barely time to slip away quietly before his double appeared.

It was in truth a difficult and dangerous game, but he played it out coolly and warily to the close. Instinctively he felt that things were growing rapidly to a climax. A new burglary was on foot; so much he could gather from stray hints. Unfortunately the coup had been planned with the real Jim Blunt, and so the knowledge of the false Jim Blunt was taken for granted. He only learnt that a crib was to be cracked some distance outside London, and that the three were to take part in the cracking. Even the night he could not make quite sure of.

He determined on a final effort at any cost to get hold of the secret.

AN appointment was made with the real Mr Blunt to call for an

old lady at the theatre. At eleven precisely the mock Mr Blunt

strolled into the inner parlour of the "Ram's Horn" with his

driving whip under his arm, as though he had just stepped down

from the driver's seat of his hansom. He had a ball of whipcord

in his hand and was platting a new cracker for his whip thong, as

was the habit of the real Mr Blunt.

Both his friends were there smoking cigars and drinking champagne out of pewter.

"Hello! Jim," cried Fulham, "up to time and before it. Want that for to-night?"—pointing to the whipcord. "Susie must put her best leg foremost." "Susie" was the sweet little mare.

"Have a touch of the whipcord yourself," he added, pushing towards him a bright tankard crowned with foam, "that will put spunk in you."

Mr Beck blew off the foam and had a deep pull of the liquor that shone golden in the glass-bottomed tankard.

"Luck!" he said, as he put the vessel down half empty. Mr Blunt was inclined to be laconic, not to say sullen, in his cups.

"Got the tools all right?" he added, pointing to the pocket of Mr Grimes, which bulged and dragged a little as with a hidden weight.

"You bet," said Mr Grimes, and he exhibited with pardonable professional pride a jemmy, a revolver, and an electric dark lantern, all of the latest and neatest pattern.

"Nasty job and nasty night," Mr Blunt's understudy grumbled hoarsely in the recesses of his pewter.

"You be d——d, Jim," retorted Mr Fulham, cheerily; "are you afraid the draught will give you a cold in your blooming nut, my rosebud? Want a big, yellow moon and a nightingale, you do. It's a picked night for our little picnic. Hark to the wind screaming like a drunken fishwife."

"It was the job itself I was thinking of worse nor the weather," he grumbled, still sulky.

"The job!" cried Mr Fulham, indignantly, "why there never was a neater thing put up since we went into business. It is as easy as kiss hands. Hubby is away for a week's shooting; missis is young and timid. The butler—the only man in the house—is a heavy sleeper, told Grimes so himself, and he ought to know. He has got twenty quid down as a sleeping draught, and he is to get twenty more when the job is through. He's that forgetful I shouldn't be surprised if he were to leave the kitchen window open and the key in the plate closet before he went to bed. Eh! Grimes?" and the wink he gave was full of expression. "The place is chockfull of silver; a regular Peruvian mine. The wedding presents alone made a column in the Times, all waiting peacefully to be carried away. If that's a nasty job I'd feel obliged"—with elaborate politeness—"for your notion of a nice one?"

"It's a long way to get to," objected the grumbler, half apologetically.

"A long way! I don't know what's come to you to-night, Jim; a long way! it's fifteen mile, not an inch more."

"I make it better nor twenty."

"Do you think it's an old-lady fare you're jawing, Jim? It's under fifteen, if anything. You goes out by Kensington, you see, and then you turns round to the——"

Mr Beck was listening with both his ears, but at this moment the shock head of the potboy was thrust in at the door.

"Hansom's waiting, gents, and——"

Then he caught sight of the mock Mr Blunt, and stood with eyes and mouth extended to the uttermost—a grotesque statue of amazement. He had been honoured with a kick and a curse by the real Mr Blunt a moment before.

But Mr Beck gave him no time for thought or speech.

"Come along!" he shouted to the others, "time's up!"

He bundled the bewildered boy out before him into the street and discreetly disappeared in the black shadow beside the door.

The others only waited to polish off their pewter pints of champagne and came grumbling out after him, and climbed into their places in the hansom. Mr Blunt was in the driver's seat, with a huge portmanteau in front of him on the roof.

"Know the way now, Jim?" Mr Beck heard Mr Fulham say to the driver.

"Do you take me for a darn fool?" was the gruff response. The trap-door on the roof was slapped down hard, the driver's whip cracked, and the hansom sped away swiftly.

For a short second Mr Beck stood helpless.

But he had hardly time to say "d——n" once when his eye lit upon a bicycle that leant against the wall while the owner had gone into the "Ram's Horn" for a drink.

"'Set a thief to catch a thief,'" he muttered between his teeth. "I'll qualify."

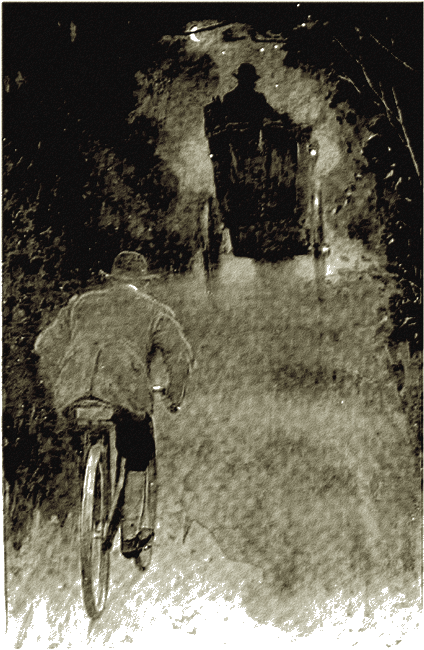

THE next second he was astride the machine, scorching down the

street in swift pursuit of the vanishing hansom.

For a while he kept pace with it easily enough, slipping in and out through the traffic like an eel. But gradually they drew clear of the town, the long road stretched open before them, and the mare flew.

Mr Beck settled himself on his hard saddle. The bicycle did not suit him. It was heavy and the stretch was too short, and the pedals brought his knees within an inch of the handle-bars as they rose. But he struggled on bravely, keeping the shadowy outline of the hansom well in view.

The road turned sharply, and the rush of the strong wind came straight against him like a broad hand on his chest holding him back. But he was a powerful rider, and he put his weight and strength into each drive of the pedal, shoving his way through the wind like a steamer through a current.

It was cruel work. The wind whistled and tore past him; his muscles ached, and the sweat fell from his bent face in big drops on the road, but he still kept the flying shadow of the hansom in view. The strain grew tenser still. He felt the pedals push back against his feet as he drove them down. The road sloped abruptly, and the vague outline of the hansom gradually merged in the darkness.

"The game is up," Mr Beck muttered through his clenched teeth, but at the same moment came the remembrance of that ball of whipcord in his pocket and a use for it.

Slacking speed for an instant, with hand and teeth he made a running noose at one end of the cord and tied the other to the handle bar. Then he grasped the handle bar tight in the middle, bent head and shoulders over it, and put all the strength of his body into one mad spurt up the hill. It was agony while it lasted. He felt the veins in his forehead swell, his heart thumped fiercely against his ribs and his breath came in labouring sobs, but still the bicycle leapt on through the wind.

Slowly the hansom came back to him. The outline grew clearer and darker. Nearer and nearer he crept, and at last his stretched fingers slipped the noose over the curl of the back rail. He had shot his bolt; he could not have kept up the terrible strain for ten yards more. He let the cord slip till it came tight with a jerk that almost whipped the bicycle from under him. But he steadied himself in a moment, and then, with a fresh wind blowing cool against his burning face, he felt his bicycle glide smoothly and swiftly uphill of its own accord in the wake of the flying hansom.

Slowly the hansom came back to him. The outline

grew clearer and darker. Nearer and nearer he crept.

He straightened his chest and drew deep breaths of the cool air into his labouring lungs, and still the bicycle flew smoothly, easily, and almost as swiftly as a bird.

So they sped on, mile after mile, uphill for the most part, with now and again a sudden dip in the road that slackened the tense cord and brought Mr Beck's hands to the brakes for a time.

AN hour and a quarter had passed—Mr Beck could guess the

time better than most modern watches—when the hansom drew

up suddenly on the crest of a long hill, and the fast-following

bicycle almost ran into it.

Mr Beck, who had been expecting a halt, saved and steadied himself with a firm grip on the back rail of the hansom, and waited and listened.

He heard the trap-door open and Fulham's voice say: "Take it easy now, Jim; the house is on the slope of the hill not a quarter of a mile off. We must get round by the back way, and leave the horse and trap in the lane. The middle window at the back is open ready for us."

Mr Beck waited to hear no more. He undid the cord from the rail, gathered it up in a loose fistful and then, where the shadow was blackest, slid silently past the hansom down the incline.

In a moment the hansom began to move again slowly and cautiously. It would almost seem as if the well-trained little mare knew silence was needed, so lightly she stepped.

All things went well with the three brave burglars. At the bottom of the lane a convenient stand was found for the docile mare, and she was left with her nose buried in a feed of old oats. The window opened at a touch, and one after another the three dark forms crept stealthily through, the last pushing the big portmanteau in to the others.

"I have the glim," Grimes whispered, and the gleam of the electric lantern lay along the black passage. They crept past the kitchen and wine cellars to a strong oak door with the key stuck in the lock. It opened on oiled hinges, and the light glittered on piles of silver.

"Cricky!" was Fulham's expressive comment as he and Grimes passed through with lantern and portmanteau, while Blunt waited in the passage with revolver ready.

The gaping mouth of the portmanteau seemed to open of its own accord to engulf the glittering treasure. It was wonderful how quickly and how noiselessly salvers and cups and bowls and jugs, with double fistfuls of silver spoons for packing, were crammed into its capacious stomach. In ten minutes it lay on the floor locked and strapped and gorged with heavy metal.

"I could do with a drink," said Fulham, straightening his back and wiping his hot face.

"I'll get one," said Grimes. "I know the way of the place." He came back with a bottle of champagne in each hand and one under his arm. "Friend in court," he exclaimed. They got the corks out in a trice and drank the foaming liquor from silver.

"Nasty job this," said Fulham, with a wink at Grimes, "eh! Jim?"

"Awful night," replied Grimes, with a responsive wink, "sorry you came, Jim?"

"Who are you coming at?" growled Blunt. "I see nothing wrong with the night, or the job, or the drink either, for the matter of that."

"Who are we coming at? We are coming at you. You don't like this and you don't like that. Aren't you ashamed of yourself, Miss Molly?"

"For two straws I'd give you a wipe across your blooming mug. I was readier for the game than you were."

"Just listen to him, Fulham, will you?" cried the justly indignant Grimes. "You was as ready as I was!"

"Ay, and readier!"

"Then why did you come whining about it?"

Blunt's big fist was clenched, and the prudent Fulham thought it time to intervene in the interest of peace.

"You're a brace of bally idiots," said the peacemaker. "Business first and pleasure afterwards. You may bash each other into small bits when we have got the swag safe. Here, lend a hand with the portmantle, Grimes; it's time to be rambling."

"What about upstairs?" said Blunt, returning to business, the more anxious to show his pluck and gumption from Grimes' sneers. "There will be whips of jewels where there's so much plate."

"Have a try while Grimes and I bring this load out to the trap," said Fulham; "there's a second lantern."

"Heavy!" grunted Grimes, as they lugged the portmanteau along the passage.

"You'd like it light, would you?" chuckled Fulham.

Blunt crept cautiously up the broad staircase, his stockinged feet sinking noiselessly in the deep velvet pile of the carpet. He paused for a moment at the drawing-room door and let a beam of light from his lantern fall across the pitch darkness of the big room.

"Nick-nacks and pictures and crockery-ware," he muttered contemptuously; "I'm not taking any, thank ye."

Softly as a great cat the burly ruffian moved up to the next floor along the narrow lane of light the lantern made for him through the darkness. In the still silence he could hear the tick of the great clock in the hall like the beating of a hammer.

To his right and left were doors. He put his hand gently on the knob to the left and turned. The light of the lantern flashed back in his dazzled eyes from a great mirror that fronted him as he entered, and glittered among the jewels that lay scattered on the dressing-table.

His delight found vent in a whispered blasphemy. Setting his lantern on the dressing-table he began to cram the jewels greedily into his knotted handkerchief.

His elbow struck a porcelain ring stand and it went down with a clatter of metal and broken china on the carpet. The gems were scattered and rolled and lay twinkling like coloured fireflies in the lantern's rays. Blunt stooped to gather them in the half darkness. He was still on his knees when suddenly the whole room flashed out in the brilliant glow of a dozen electric lights.

Turning round sharply he saw a lady fronting him not five yards away.

She was graceful and beautiful as a statue in her long white night robe, fastened with a knot of blue ribbons at the throat. Her naked feet peeped from under the lace trimming pure white on the rich carpet. Down to her waist her hair fell in a tangle of ripples and curls. Her face was white even to the lips, but her blue eyes shone big and bright, and she held in her right hand a revolver grasped tight by the barrel, the muzzle pointing at herself and the butt at the burglar.

Jim Blunt was not in the least affected by this vision of pale beauty. To him she was merely an unwelcome interruption of business.

"Drop it!" he growled, referring to the inverted revolver.

She dropped it obediently and it exploded as it fell and a shrill shriek followed the report. The room was full of the stinging smoke of gunpowder.

Jim Blunt cursed volubly.

"Shut your blooming mouth!" he cried; "quit squealing or I'll put a bullet in you!"

A second shrill shriek answered and the lady opened her lovely lips wide for a third.

Blunt whipped out his revolver and pointed it, right side forward, straight at her breast.

The scream was frozen on the lady's lips by sheer amazement, when straight behind the ruffian she saw his own counterfeit suddenly appear moving swiftly and silently as a shadow.

The revolver in Jim's hand went up with a sudden jerk, boring a round black hole in the white ceiling. A strong arm gripped his bull neck from behind and brought him choking and sprawling on his back on the carpet. The next moment he lay with handcuffs on his wrists and a gag between his teeth, prone and helpless.

A strong arm gripped his bull neck from behind and brought

him choking and sprawling on his back on the carpet.

Again the lady screamed shrilly.

"Not any more please, Mrs Meredith," said a familiar voice persuasively.

"Mr Beck!" she gasped out in utter amazement.

"Take it coolly, my dear lady, the surprise is nearly as great on my part, I assure you, at this pleasant meeting. I will explain everything later on. Just now I have a lot to do that won't wait. I am afraid I must leave this brute here with you. Don't look so frightened! he's quite harmless. I'll tie his feet and kick him into the bathroom."

He drew the serviceable ball of whipcord from his pocket and strained it tight, coil after coil, round Blunt's legs and arms till he lay parcelled up stiff and helpless as a log.

"You can make the maids roll him downstairs into the cellar if you like later on," said Mr Beck—"no! not the butler, I have taken the liberty of turning the key on the butler. You had best leave him where he is till I come back for him."

Hark! His keen ear caught the noise of the men below climbing back through the window. There was not an instant to spare. He pushed the prostrate and helpless Blunt with his foot across the carpet into the bathroom and turned the key in the door.

"Good-bye," he said, re-adjusting the false nose that had got slightly displaced during his exertions. "Our friends have heard the shots. I don't wish to give them the trouble of coming up. I'll meet them on the stairs."

He passed out quickly, closing the door after him. Not a moment too soon.

"That Jim?" said Fulham in a cautious whisper.

"Stow your noise!" Mr Beck growled in the identical voice that was at that moment corked up by the gag in the mouth of the recumbent Mr Blunt.

"Stow your noise, it's all right, I'm coming." He joined them on the landing opposite the drawing-room door.

"Why the blazes did you use the barkers?" growled Grimes.

"'Cause I had to; she was squealing like a mad steam-engine. I laid her out safe the second shot. She'll tell no tales; but it's about time to be off. I've got the swag safe enough," and he showed the heap of trinkets that poor Blunt had so industriously collected.

"Right you are," answered Fulham, "the luggage is up and the mare ready."

There was a pounding noise on the floor over their heads.

"Listen!" said Grimes, "there is someone kicking. You haven't made a clean job of it, Jim, she wants another dose of lead; I'll quiet her."

He turned to go up the stairs but Mr Beck's strong hand dragged him back. He knew whose hob-nailed boots were kicking the bathroom floor. "Let be, I tell you; it's her last kick; she's got a brace of bullets in her skull. I can do my work without your helping."

He pushed Grimes roughly down the stairs before him, Fulham following. So through the window they passed and down the lane-way where the hansom stood and the mare ready waiting with ears cocked.

Grimes and Fulham got to their places and Mr Beck climbed to the driver's seat with the big portmanteau tied in front of him.

He closed the wooden apron across their knees and let the plate-glass shutter down half way to meet it.

The gallant little mare started as fresh as ever and they bowled swiftly on noiseless, rubber-tyred wheels back to town.

GRIMES and Fulham had carried a couple of bottles of champagne

with them and the noise of the popping corks was heard presently

in the interior of the hansom. After a brief interval a bottle's

neck was protruded through the trap door at the top.

"I'm not taking any," said the driver, "I have the mare to look after—and you."

"Good old Jim!" said Grimes, effusively, elated at the prospect of more drink to share, "we can trust Jim to see us through. He knows where we are bound for, better nor ourselves"—which was truer than the speaker thought.

The two bottles were duly emptied and the two inside passengers were pleasantly drowsy though not in the least drunk. They leant back at either side on the comfortable cushions while the hansom sped on its smooth, noiseless way to London.

Now they are sweeping through the silent town in the grey light of the early dawn. The streets seemed a little unfamiliar to their sleepy, half-opened eyes. But they had the most perfect confidence in Jim.

Their confidence was rudely shattered. The hansom took a sharp turn and drew up with a scramble at the entrance to Scotland Yard. The plate-glass shutter was let slip down on the wooden apron and Mr Beck leapt from his seat to the pavement.

"Hurry up! Hurry up!" he shouted, as four or five men came rushing out, while the two figures trapped in the hansom struggled madly like wild beasts in a cage. "Here are two of the suburban burglars, with their luggage, come to stay. Kindly help the two gentlemen out and make them comfortable while I go back for the third, who has arranged to wait for me."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.