RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

"The Quests of Paul Beck,"

with "The Ship's Run"

M. McDonnell Bodkin

Irish barrister and author of detective and mystery stories Bodkin was appointed a judge in County Clare and also served as a Nationalist member of Parliament. His native country and years in the courtroom are recalled in the autobiographical Recollections of an Irish Judge (1914).

Bodkin's witty stories, collected in Dora Myrl, the Lady Detective (1900) and Paul Beck, the Rule of Thumb Detective (1898), have been unjustly neglected.

Beck, his first detective (when he first appeared in print in Pearson's Magazine in 1897, he was named "Alfred Juggins"), claims to be not very bright, saying, "I just go by the rule of thumb, and muddle and puzzle out my cases as best I can."

...In The Capture of Paul Beck (1909) he and Dora begin on opposite sides in a case, but in the end they are married. They have a son who solves a crime at his university in Young Beck, a Chip Off the Old Block (1911).

Other Bodkin books are The Quests of Paul Beck (1908), Pigeon Blood Rubies (1915), and Guilty or Not Guilty? (1929).

— Encyclopedia of Mystery and Detection, Steinbrunner & Penzler, 1976.

IT began this way. She dropped her purse and he caught it as it fell. Don't run away with the notion that this was the starting point of a romance, for though the lady was young and pretty there was a wedding-ring on her finger, and the man was stout, sedate and middle-aged.

They were standing together on the upper promenade deck of the great ship Titanic as she slid in the grey dusk, a softly-moving island, in and out through the multitudinous shipping of New York harbour. A soft mist was over the sea and the sky, stealing away their colour. The huge Statue of Liberty stood up from the smooth floor of the sea like a fine grey etching against the fainter grey of the sky. High up in the lifted hand of the great figure the beacon flared red through the haze. The dawn grew slowly—the mist changed from grey to white, from dark to light. There was a luminous splash of brightness in the clouds to the east, and without warning the blood-red rim of the sun showed over the water.

It was at that instant that pretty Mrs Eyre dropped her purse as she leant over the rail, and Mr Rhondel, with a snap like a swooping hawk, caught it a yard from her hand.

"Cricket!" he explained, as he restored it to the fair owner.

"Thanks," she said; "you're real smart. There were five hundred dollars in that purse on their way to the bottom of the sea, when you chipped in and caught it. Say, isn't that just fine!" she waved a small hand admiringly at the red sun—"guess he knows how to wake things up rather."

"Going over for the first time?" said Mr Rhondel, ignoring the opportunity of discussing the sun's capabilities.

"First time, Bob and I, to the old country."

"You're Irish, then?"

It was a bold shot. The girl—she was hardly a woman—was typically American, tall, slim, graceful, carrying her head well: and her voice had a faint twang of the American drawl, which is pleasant from pretty lips. But the shot was straight, all the same, and went home. The eyes of forget-me-not blue deepened to violet.

"Am I Irish? Why, sure; and Bob, too. My grandfather by the mother's side came over in the forties. But Bob is Irish all the way through, from his toe-nails to his top-knot. There goes the bugle for breakfast. Come along; we'll get together, we three. I'll fix it all right with the steward; you'll like my boy."

She fixed it all right, and Mr Rhondel sat beside her at the bounteous breakfast-table. Beyond her, on the other side was her "boy"—a handsome, clean-shaven young fellow of twenty-five.

"Where have you been, Kitty? I've waited a minute and a half, and I'm as hungry as a hawk."

He dexterously peeled a big apple as he spoke.

"Seeing the sun up," Kitty exclaimed, "and carelessly dropping my purse over the rails."

"I'm sorry."

"It's all right; don't worry. Mr Rhondel, here, caught it as it fell. This is Bob, Mr Rhondel—Bob Eyre, my husband; you can shake hands behind my back."

She drew herself straight and close to the table, and they shook hands behind her back, Mr Eyre with an admiring wink at the shapely little poll on which the coils of glossy, red-brown hair were piled.

"Try a kippered herring, Mr Rhondel," said Bob, "with tenderloin steak to follow—best thing to begin breakfast with. Sole for you, Kitty?"

They chatted freely all through the long breakfast, and by the time it was over they were old friends. Mr Rhondel manoeuvred his deck chair close to Mrs Eyre, making no secret of his admiration. Bob Eyre sauntered off to play deck quoits. There was quicksilver in the young fellow's blood. He could not sit still for a moment; brain and muscle were full of restless vitality that craved incessant exertion and excitement.

LIFE on board soon settled down to a routine. On the third day

out the same hour found Mrs Eyre and Mr Rhondel seated on their

deck chairs close together, and Mr Eyre playing shuffle-board.

"May I smoke?" said Mr Rhondel.

"Why, certainly. I love a cigar in another person's mouth; don't smoke myself, not a cigarette even; don't like it."

She carefully found her place in her book, and then set it face down on the rug that Mr Rhondel had tucked cosily around her.

"You are the great South African millionaire, aren't you, Mr Rhondel?"

"So they say."

"Oh, you need not get riled. I wanted to give you a word of warning; there's cardsharpers aboard. I coaxed it out of the doctor. They plucked so many pigeons the last few voyages that now the company has a detective to watch them. The doctor wouldn't or couldn't tell me which was the detective. I guess myself it is the curate, the Rev. Abel Lankin."

"Surely not!" said Mr Rhondel.

"Well, I suspect him. He looks too innocent to be natural. Look at him now with the fool woman over there. Isn't he a pretty buttercup? Well, I hope he'll catch the cheats, anyway."

Mr Rhondel hoped so, too, and then their talk drifted lazily from one subject to another as the great vessel—the largest and fastest passenger boat afloat—slid smoothly through the waves.

Mrs Eyre was sudden and frank as a child in her friendship. She told him all about herself, and all she knew about her husband.

"I worked the 'phone in New York," she confided. "My folk could have kept me at home, but I wouldn't. Bob was a conductor on the street cars when I met him; he was an inspector when I married him. We went to Niagara for the honeymoon and concluded the celebration in the Manhattan Hotel till the dollars ran out. We had fixed it up to live in New York, and we were on the look-out for a flat when the news came that started us homewards."

"What news?" said Mr Rhondel, as he lit a cigar carefully all round from the glowing stump which he tossed overboard into the froth of waves. This frank-spoken little woman interested him. It was not mere politeness that prompted the question.

"Oh, you have got the soft end of the talk this time. It is easy to say: 'Well, what's the news?' It's not so easy to answer you slick. I'm not clear about it myself; I doubt if Bob is. I had to get the story out of him in bits, like the kernel out of a walnut, and some stuck. He was a landlord once over in Ireland. But there wasn't a cent in the job. His income was considerably less than nothing a year when he started for the States, leaving his lawyer in charge of the mortgages.

"He often told me he was the first man of his breed that had ever earned a cent. Then the British Congress passed some Act or another to boom real property, and Bob's land came in on the top of the boom. I don't know what happened. The tenants bought the land, and the State paid for it, and they paid him a bonus for selling at a big price.

"Then the State Legislature, the Senate, House of Lords, or the King of England for all I know, bought Bob's castle and demesne lands, and sold them back to Bob for less than was paid for them, and made him a free gift of the balance. It was all set out in the lawyer's letter; and I couldn't understand a word of it, but the end was plain enough. Bob had fifty thousand pounds clear out of the deal, and the old castle was waiting for him on the other side.

"'We'll take on the job, Kitty,' he said to me; 'you'll like it and I'll like it. I always got on well with the boys, though we had our little differences about rent. I reckon they'll be glad to have me back, and Mrs Kitty Eyre will make the county folk sit up. Between us we'll set things humming. Fifty thousand pounds is a fortune in Ireland. I'll give the boys a lead in farming. There's money to be made out of land if one knows how to make it. We'll start a poultry farm and dairy farm. I'll give you your choice, Kitty, and I'll lay a hundred dollars I beat you on the year's return.' I took him up. I've backed the chicken coop against the milk pails, and I mean to win, sure."

JUST then Bob Eyre in grey flannels and bright-yellow,

rubber-soled shoes came sauntering up, flushed with his efforts

at shuffle-board—a fine, shapely cut of a man, with a figure that showed breeding like a thoroughbred horse: light on his feet, and agile in his motions as a cat.

As he reached his wife he opened a shapely hand and showed a fistful of money, silver and gold.

"Won it with the shovel," he explained. "The other chap fancied himself more than a bit."

He dropped down on the deck close to his wife's feet, and pushed his tweed cap back from a tangle of crisp curls.

"I'll make another bit," he said, "before we touch land; you see if I don't. Play poker, sir?" he said, turning abruptly to Mr Rhondel.

"Sometimes," said Mr Rhondel, smiling at a pleasant reminiscence. "Do you?"

"Rather, only in a small way up to this—half-dollar rise and five-dollar limit. I take it a gentleman should never risk more than he can pay when the last hand is played. But I'd like to have a chance of a real game. I fancy I'd sweep the board."

"Why don't you?" asked Mr Rhondel, carelessly.

"Cannot. The captain has forbidden big play. He's a sportsman all right himself—says he's very sorry, but company's orders must be carried out. There's a 'tec on board—a whipper-snapper chap, rigged out as a sky pilot, nosing round. Old Colonel Rollin pointed him out to me when I hinted at a game. 'No use, my boy, when that chap's around,' he said. 'Eyes like a ferret.'"

"I'm real glad, Bobsie," his wife interposed, "the big game is barred. I know you. You'd bet the fifty thousand pounds on a pair if you thought the man next you was bluffing, and you'd laugh when he raked in the pool on a straight flush."

"Give us a chance, little one, I'm not that sort. Besides, it's my last hope of a flutter. I have promised never to bet more than five dollars on any game after we touch Old Ireland, and you know I'm a man of my word."

Miss Phoebe Everly passed at this moment—a genuine Gibson girl, with superlative curves and restless activity.

"Lazy!" she threw the word back at Bob Eyre as she passed, and he leapt instantly to his feet at the challenge.

"Have a game of shuffle-board?" he retorted.

"No, come for a smart walk instead. I want to ask you something."

She nodded a gay little nod to Kitty and carried him off.

"Well?" he said when they were half up the promenade deck, "what's your question? If it is the question, I cannot—I'm married already."

"Don't trouble on my account. I'll never take a hand in that gamble. I want you to tell me what they mean by 'a bit on the run.'"

"Don't know."

"Then find out like a good boy. I heard old Colonel M'Clure talking to Pop at lunch a lot of stuff about the day's run and the auction of the numbers and the high field and the low field. But when I asked him what it meant he told me to run away and play, it wasn't good for little girls to know everything. So I want to find out just to spite him."

"Leave it to me," said Bob Eyre, "if it's a bit of a gamble, and it sounds like it, I'll be glad to find out on my own account."

PRESENTLY he accosted Colonel M'Clure with a diplomatic

question or two, and found him most genial and freely

communicative. His ruddy face and white hair and whiskers gave

the old Colonel a benevolent, Father Christmassy appearance. But

his was not the goody-goody order of benevolence, for he could

drink his glass and tell a story with the best, and his jolly

laugh was a pick-me-up to a man in low spirits.

"The run of the ship!" he cried in reply to Bob Eyre's frank question. "My dear boy"—he was of the kind that call all young men dear boys—"don't tell me you have never heard of the lottery on the run of the ship."

"Won't you let me tell the truth, Colonel, once in a while? Remember, I've had only one voyage before, and that was steerage."

"Well, you've come to the right shop for information. I've been auctioneer and general boss of the lottery a score of times. Couldn't live through the voyage without it. The trip takes considerably less than no time when you have the lottery going, you bet your bottom dollar on that. I tell you what, sir——"

"Easy there!" Bob Eyre broke in upon the enthusiast before he got into his stride. "First tell me, if you please, what the thing is, anyway."

The Colonel passed from enthusiasm to explanation.

"You know the little map hanging in the broad passage between the library and the smoking-room on the upper deck?"

Eyre nodded.

"Then you have seen the day's run of the vessel is drawn each day on that map in a red line across the blue sea, with the length marked in plain figures?"

"With the last voyage marked in full," added Eyre.

"Exactly, my boy. I see you have your eyes skinned. Perhaps you have noticed that the length of the day's run ranges from about four eighty-five to five-twenty. The variation is twenty or thirty miles, and the average run about five hundred. Now, here is the way the lottery is worked. A score of us—more or less—have a pound each in the pool. We put numbers up to a certain limit in a hat—say from 490 to 510—and draw. Whichever number hits the ship's run for that day scoops the pool. See?"

"But I don't see——"

"Easy on, my boy. I know what you were going to say. Maybe none of the numbers would hit the ship's run. To meet that chance there is the 'high field'—all numbers over the highest number in that hat—and the 'low field'—all under the lowest.

"But that's not the whole game either. The best is to follow. The numbers, after they are drawn, are put up to general auction. A man may bid for his own number. If he buys it in he has only to pay half the price into the general pool. If an outsider buys, the owner gets half the price bid, and the pool takes the other half. The 'high field' and the 'low field' are not drawn for at all, but auctioned right away. The auction is the real fun—eh, what?"

"A bully game!" cried Bob Eyre with enthusiasm. "Is there room for one more inside?"

"We'll try to squeeze you in, my boy. The draw will be in half-an-hour's time. There are seventeen in already; you'll make eighteen."

LATER on, when Bob, as in duty bound, tried to explain the

mystery to Miss Phoebe, she cut him short midway without mercy.

"It sounds like a conundrum, and I hate conundrums," she

said.

But Bob found her father, Judge Everly, there when he came to draw his number that evening. Mr Rhondel was also beguiled into taking a hand in the game. The bidding in the smoking-room ran its lively course amid a storm of good-humoured chaff to which Colonel M'Clure was the main contributor.

Bob Eyre persisted that it was a bully game, in which view he was confirmed when two days later he scooped the pool of £134 with the figure 505 which he had bought at the auction for £11, having sold his own figure 504 for £10.

He was intoxicated with his success, stood drinks all round, and strutted about next day, with his tail up, to where his wife sat on the deck chair reading placidly.

"I told you so, Kitty," he crowed. "I knew I could meet and beat the knowing ones at their own game. Just a little bit of head work, that's all. I took a note of the wind and the weather, and picked the right number out on my own judgment first try. It's a little bit of all right, my dear, and here's your share of the winnings." He poured a clinking stream of gold coins into her lap.

"I wish you would leave it at that, Bob; I'm afraid."

"Fear killed a cat, or was it care? it does not matter which; don't let either kill my mouse. Keep your eye on your hubby, he'll see you through. I only wish I could get these johnnies to pile it on a bit. I don't care for this game of chuck farthing."

THAT evening, when they were only one day out from Queenstown,

Bob Eyre had his wish. The boat had been making great time of

late, averaging 515 miles a day, and there was general surprise

when Colonel M'Clure, to whom the arrangement of the figure was

intrusted for the most part, fixed the range of the lottery from

485 to 510.

"It's a dead cert, for the 'high field,'" objected one of the coterie.

"Don't you believe it," retorted the Colonel. "Fine weather cannot last for ever. I have crossed more times than you, my boy; there is generally a bit of a blow as we come close to the poor distressful country. I don't mind having a try at the 'low field' myself, I can tell you."

The majority were, however, of the other way of thinking. The sky was without a cloud, the wind behind them, the glass going up. "Shouldn't mind betting an even pony," said one languid youth in grey flannels, "that we do our 520 this run."

"Done," cried the Colonel so sharply that the languid youth's jaw fell, and he abandoned the opposition.

Then Colonel M'Clure developed an unexpected vein of obstinacy. He seemed hurt that his judgment was questioned, and the talk began to grow hot when Judge Everly, in the interests of peace, came round to the side of the Colonel.

"Easy with the pepper castor, gentlemen," he said, "let the Colonel have his way. It's as good for the goose as the gander. We can each back our own fancy in the lottery, and the laugh will be on him when the 'high field' romps in an easy winner."

Bob Eyre joined in on the same side, and the Colonel carried the day.

"I know the Colonel was all wrong, of course," Bob confided to Kitty, "but it was not my cue to tell him so. So I kept my eye on the 'high field' as a dead cert."

THAT night there was wild excitement in the smoking-room when

the numbers were put up to auction.

Colonel M'Clure, wielding a huge pipe-case for an auctioneer's hammer, was better fun than ever. His good-humoured jests were like oil on the troubled waters of the gamblers' feverish excitement. For the bidding ran high. By a chance, lucky or unlucky, the Rev. Abel Lankin, whose protesting presence was always a check upon any kind of gambling, did not put in an appearance.

The high spirits of the company, excited at the thought of approaching their journey's end, found a vent in high betting. Number after number was bid close up to three figures. The bigger the number the bigger the bidding, but when the Colonel reached the "high field," which looked so like a certainty, the company threw their self-control completely away, and the bidding was fast and furious. All joined in at first, and three hundred was bid before the pack began to thin off.

When five hundred was reached three men had the bidding between them—Judge Everly, thin-lipped and determined; Colonel M'Clure, full of jovial good-humour; and Bob Eyre, more reckless than ever from a slight overdose of champagne. These three kept capping each other's bids with monotonous regularity, while the rest of the company sat silent with the secondary excitement which high gambling always begets amongst the onlookers. The bidding mounted up and up, five pounds at each jump, until it seemed it would never stop. At three thousand pounds Colonel M'Clure suddenly gave way.

"I'm out of it," he said, pausing to mop his red face with a big silk handkerchief, and sucking hard at a huge cherry cobbler crowned with small icebergs that stood beside him, "this is too hot for me! Any bidding after three thousand?"

"Three thousand and five," said the Judge, in a dogged voice.

"Guineas," shouted Bob Eyre, defiantly.

That settled it. There was a long, breathless silence. The Judge seemed to hesitate for a moment. A bid hung poised on the tip of his tongue; then with an angry movement he abruptly turned his back on the auctioneer.

"Three thousand one hundred and fifty bid," Colonel M'Clure went on imperturbably. "Any bid after that? Now's your time, gentlemen, to make your fortune; going for a trifle, the chance of a lifetime. You will be cursing to-morrow when our young friend here rakes in the pool. Going! going! gone! The 'high field' to Robert Eyre, Esq., for three thousand one hundred and fifty to be paid into the pool."

It was thought that the auction of the "low field" would be a very tame business after this. The "low field" seemed so plainly out of the running that it looked as if the Colonel could buy it for a song; but a surprise awaited the company.

Mr Rhondel, who had been drinking silently and steadily while the auction was in progress, apparently impervious to the excitement around him, now suddenly took a hand in the game.

To all present it seemed a case of a born gambler suddenly breaking loose from the curb of self-restraint and letting himself go. He bid with mad recklessness. Bob Eyre had been cool and prudent by comparison.

The company looked on in amazement. It was a duel to the death between two men—Mr Rhondel and the auctioneer. At first Colonel M'Clure was inclined to jest at his opponent while the bidding mounted rapidly.

"All the better for the pool, boys," he said with a side wink to Bob Eyre, who sat at his right exulting in his own "dead cert."

But when Mr Rhondel took to piling it on fifty at a time the jovial Colonel's manner changed. His face hardened; he threw away his cigar, put aside his cherry cobbler, called for a brandy-and-soda, and went to work doggedly.

There was not a second's interval between the bids, and the total mounted with bewildering rapidity. It was a fierce contest, but a short one—the pace was too hot to last.

At four thousand and fifty Mr Rhondel suddenly collapsed, and, after a long delay and many urgent appeals to the company to come in and make their fortunes—"It was just picking up money"—the jovial Colonel, his good-humour now completely restored, knocked the "low field" down to himself.

Then there was the reaction after the excitement. The high figures had sobered the company. Through the dead silence the clear, incisive voice of Judge Everly was heard:

"This is a big gamble, gentlemen," he said, "and a ready-money business, I take it. There should be about seven thousand three hundred all told in the pool. I vote that we settle up and appoint a stakeholder before we part."

There was a murmur of approval. "I'm agreeable," said Bob Eyre, "I will pay in at once spot cash. I beg to nominate Mr Rhondel as stakeholder, as he is out of the gamble."

"I will be glad to have Mr Rhondel if he has no objection," said Colonel M'Clure, cordially, "though he did push me to the pin of my collar that time. Another fiver and I would have knocked under. But I love a stout fighter."

Thereupon Mr Rhondel, whose excitement seemed to have completely fallen away when he was knocked out of the bidding, declared his readiness to act.

Several of the men retired to their cabins for chequebooks or money. Eventually the entire amount to the last penny was paid over to Mr Rhondel. There were several cheques, but Bob Eyre, Colonel M'Clure and Judge Everly, who between them contributed more than nine-tenths of the pool, plumped down spot cash.

Mr Rhondel gave a receipt for the money and left the saloon, one pocket bulging with a huge roll of notes and cheques to the tune of seven thousand three hundred pounds, and the other with a heavy revolver of the latest pattern.

He had a few minutes' talk with Mrs Eyre, who was seated in the starlight waiting for the news of the final gamble, and to whom he gave a brief and graphic description of the exciting scene in the smoking-room.

"Three thousand guineas!" said the little woman, dolefully. "How many dollars in that, I wonder?"

"Fifteen thousand seven fifty," replied Mr Rhondel, promptly.

"That makes it sound a deal worse. Fifteen thousand seven fifty dollars gone in a snap of the fingers to the bottom of the sea!"

"Don't say that, young woman. See, I've got it here in this pocket-book, with a lot more of other people's money."

"I've a great mind to rob you."

"Better not." He showed the butt of a big revolver protruding from his pocket.

"Sit further away," she cried in affected fear, "the brute might go off; besides, I'm ashamed of your getting mixed up in things of this kind, and encouraging Bob to scatter his dollars. At your age, too!"

"What would you say if I handed the pocketbook and all its contents over to you to-morrow?"

"You don't mean it, of course, but I could almost kiss you if you did."

"I hate that word 'almost.'"

"And I hate that word 'if.'"

"If I drop out 'if,' will you drop out 'almost'?"

"Sure."

"Good-night, then, and mind I'll keep you to your word. I've an early start to-morrow morning. The parson chap has arranged with Anderson, the chief engineer, to show him over the engines and machinery at eight o'clock, and I'm going too. Halloa, Mr Anderson!"

A stout, dark-bearded man with a clever, resolute face, passed them, peering into the semi-darkness as if in search of somebody.

"Yes, I'm here and want a word with you," said Mr Rhondel. "Good-night again, Mrs Eyre, and don't forget your promise."

The two men walked up and down the full length of the deck half a dozen times at least, talking earnestly.

The two men walked up and down the full length of

the deck half a dozen times at least, talking earnestly.

"It's the only way," Mr Rhondel said at last.

"And a dang good way too," retorted Sandy Anderson, "if you're right in the rest. I'm your man to the finish. You do your part, I'll do mine. See you to-morrow morning at eight; meanwhile take care of yourself."

AN early party of five curious sightseers, including Mr

Rhondel and the parson, passed through a long passage to the

steerage decks, where already a number of the early-rising Irish

"boys" and "colleens" were strolling affectionately in couples,

and talking, doubtless, of the old land.

"This way, gentlemen," said Mr Anderson, and opened a door that led to a long iron staircase running down to the hollow womb of the big boat. The chief engineer welcomed them heartily to his kingdom of steel and steam. Looking down through the open ironwork of the hard-working giants in the yawning cavern, they had only a vague, confused vision of rushing pistons and revolving cranks. But Mr Anderson led them down the interminable iron steps to the very den of the monsters.

He answered all questions with the pride and delight of a fond father when his clever children show off before strangers. Because his admiration of those wonders was the most demonstrative of all, the Rev. Abel Lankin came in for most attention. The curate was like a child in his frank surprise and delight at the steel miracles around him.

He pointed to one of two huge columns of polished metal a hundred yards long that ran from the engine-room right through the stern of the steamer.

"That's the rod of the screw," said Mr Anderson.

"Rod!" cried the Rev. Mr Lankin, in amazement, "it's more like a church pillar. What does it do?"

"It pushes this big ship, twenty-three thousand tons of steel without the extras, through the sea, rough or smooth, it doesn't matter which, at the rate of twenty miles an hour. Takes it easy, doesn't it? Put your hand there."

Mr Lankin touched the shiny steel with timid fingers.

"It doesn't seem to move at all," he said.

"Oh, it moves right enough, or this ship wouldn't move. The surface is so smooth you don't feel it. Easy on," he added laughingly, as Mr Lankin stepped from the gangway down beside the revolving column, "easy there, or you will burst your way through. There's no more than three-quarters of an inch of steel between your foot and the ocean."

"Am I so near the surface?"

"You are twenty feet under the surface, sir, and that's as near as you want to go to land in that direction I'm thinking. Come along, there are other things worth seeing."

But Mr Lankin wouldn't budge an inch.

"What are those little holes for?" he said.

"For oil," Mr Anderson answered good-naturedly, as humouring a child.

"And if you don't put oil in?"

"The metal would get red-hot, maybe melt, and someone would have a wigging, you bet."

At last Mr Lankin tore himself away, and followed with the exploring party through the great cavern lit with electric light, and fresh and cool with clean ocean air sent down through the ventilating shaft that captured the Atlantic breezes a hundred feet overhead. The fascination of the great propeller shaft, however, still held the curate's imagination amid all the mechanical marvels of this cave of mystery. The white-hot furnaces, the swinging cranks, the purring dynamos, could not capture his attention.

He crept quietly back for a last look before he returned with his party to the upper air. Mr Anderson was plainly impatient at the delay.

"You should keep with the party, sir," he said sharply, when the meek little curate showed himself at last, "you might easily get hurt by the machinery."

Undeterred by this sharp rebuke, and with a muttered apology that he had forgotten his cigar-case, Mr Rhondel bolted back into the hold. The genial Mr Anderson tugged at his short beard irritably, but he said no word. Mr Rhondel was back again in a moment, his cigar-case ostentatiously in his hand. He muttered a few words of apparent apology to Mr Anderson that were inaudible to the rest of the company.

But whatever he said failed to bring Mr Anderson back to good-humour. The genial guide was suddenly transformed into the curt official.

"Kindly show these gentlemen their way back," he said sharply to one of his subordinates. "I've got my work to attend to."

Without a word more he turned his back on the party and again went swiftly down the long ladder to his own restless dominions.

THE party had scarcely got safely up to the deck when a

strange thing happened. The throbbing and heaving of the giants

in the hold, which day and night sent an incessant tremor through

the huge bulk of the vessel, suddenly ceased. Swiftly and

smoothly at first, and then slowly and more slowly, the great

ship slid forward over the smooth sea till at last she lay quite

still:

"As idle as a painted ship upon a painted ocean."

Then a wild hubbub arose amongst the passengers.

In less than a moment the captain was down amongst them, cheerily assuring them that there was not the slightest danger. There had been some slight trouble with the machinery, which would be put right in less than no time.

Still the ship lay motionless for a long hour, and the excitement amongst the gamblers was every moment more intense. Colonel M'Clure puffed himself out triumphantly, taking all the credit of the hindering accident to his own sagacity.

"I knew the 'low field' could not lose," he said. "What have you chaps to say for yourselves now?"

"Luck, pure luck," grumbled Bob Eyre, who every moment saw his chance slipping away from him. "Bar accident the 'high field' was a sure thing; but there's no fighting against luck."

"Accidents will occur in the best-regulated ships," chuckled the Colonel.

He seemed a bit disappointed when, after about an hour, the big ship began again to slip through the waters, slowly at first, but with momentarily increasing speed. He took out his gold repeater.

"I reckon," he said, "she has lost a good twenty miles by her trouble, whatever it was. The pool is as good as mine."

At about half-past eleven Mr Rhondel appeared on deck hastily, and gathered the Judge and the Colonel and the rest interested in the pool into the smoking-room. He seemed nervous and excited.

"I have found something out," he said, "from Anderson, which I want you all to hear—especially you, Judge; and you, Colonel, as you are the most interested. I want your advice."

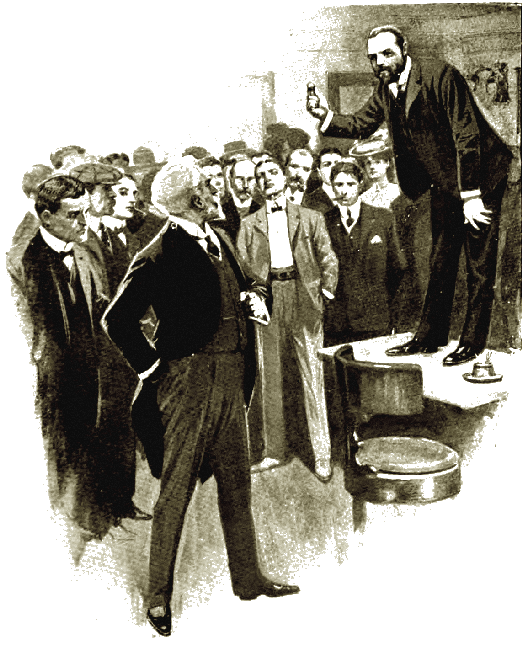

"Get up on the table," cried the Colonel, good-humouredly. "Some of you chaps shut the door, and don't let anyone else in. We don't mind the ladies, bless 'em, but we don't want eavesdroppers. Now, my boy, fire away!"

Mrs Kitty Eyre had come into the room with Miss Phoebe Everly and two or three other ladies. But there was no sign of the Rev. Mr Lankin, and all knew whom the Colonel wished to keep out.

Mr Rhondel, mounted on a table, looked round at the eager circle of listeners till his eyes rested on Colonel M'Clure and Judge Everly, who stood close to the table together. He startled them by his first words.

"There has been foul play," he said—"the machinery in the ship's hold has been tampered with. That's how the vessel was stopped."

The smile died out of the Colonel's frank blue eyes—the genial face set hard. As if by instinct his right hand went down to a hip pocket that held his weapon.

The smile died out of the Colonel's frank blue eyes... As if by

instinct

his right hand went down to a hip pocket that held his weapon.

"Have a care, sir," he snapped out—"have a care. Do you accuse any gentleman here of foul play?"

But Mr Rhondel went on, bland, conciliatory, unabashed.

"Certainly not, Colonel—most certainly not, Judge. I accuse no one, I only state the facts. After the chief engineer had shown a party of us over the hold this morning, this was found sticking in one of the holes for oiling the screw rod." He held up for all to see the half of an hour-glass, full of sand.

"How do you know it was found?" queried the Judge.

"Well, I, myself, found it. I went back for my cigar-case and found it. Only just in time—a minute more and the machinery would have been white-hot, and would have melted with the tremendous friction, and the vessel stopped for the day. As it was, there was an hour's delay to clean and oil."

"Well," said the Colonel, briskly, "assuming all this rigmarole is true—what have we got to say to it?"

"What about the stakes I hold?" queried Mr Rhondel, "are the bets off? I wanted to make sure before the day's run is announced."

"Not likely," roared the Colonel. "I'm too old a campaigner to be diddled in that style. If 'low field' wins, I take the pool."

"Hear, hear!" cried two or three of the men who had got low figures and fancied their own chance. Then Judge Everly spoke out sharply.

"The gamble was unconditional," he said, "every man is entitled to his chance. I have no interest in the thing one way or the other."

"I say so too," chimed in Bob Eyre, "a bet is a bet, and I'm not the one to squeal if the luck goes against me."

That settled it. There was a general murmur of assent.

"Then the figure of the day's run takes the pool," said Mr Rhondel. "I've no objection to that; I only want to know are you all agreed?"

"All!" they cried with one voice.

He looked at his watch, still standing on the table.

"In five minutes the captain will be here to tell us the day's run."

THE five minutes seemed five hours, so intense was the

excitement. A low buzz of talk was in the air, like the eager

whispering of a swarm of bees. It ceased in dead silence when the

captain's handsome face showed at the door.

"Ladies and gentlemen," he cried in a pleasant voice that filled the silent room, "I've good news for you. In spite of the little trouble this morning we've made the record of the voyage. The run is 521 miles. I will have the figure marked on the chart."

The door had closed on him before the amazement in the room had found its voice. The impossible had happened—the "high field" had won!

"Three cheers for Bob Eyre," someone cried suddenly, and the cheers were given with a will that showed how popular was the winner.

"Ladies and gentlemen," cried Mr Rhondel again, and there was a new and dominant note in his voice that instantly captured attention. "You would like to know the answer to this riddle—perhaps I can help you to guess it. Don't go, Colonel, don't go, Judge, my remarks are particularly intended for you. Have you ever heard of a Mr Beck?—Paul Beck at your service." He plucked off his brown beard as he spoke and whisked away a pair of bushy eyebrows, and his face seemed to change its expression, almost its features. Mr Rhondel disappeared—Mr Beck arrived.

"Ha! I thought so," he exclaimed—for the two men stared at him open-mouthed. "I have met the Judge and the Colonel before, and it's pleasant to be remembered by old friends. Well, the Blue Star Company were kind enough to think I would be useful on board. There had been too much professional gambling on their ships of late.

"Somehow, when I saw you so keen on the 'low field,' I thought it possible that something might happen to the machinery this morning—coincidences are always occurring. That's why I made you pay for your fancy. My good friend Anderson ran the ship at extra speed all night, in case by any chance there might be an accident in the morning. It was Mr Lankin who left this pretty little toy behind him by accident in the engine-room. Lucky, wasn't it, that I found it before it had done much harm. You don't know Mr Lankin, of course, Colonel; nor you, Judge? He just played this monkey trick off his own bat for the fun of the thing. Never had a thought about the 'low field' when he did it. No one would suggest such a thing as collusion. But we needn't go into that, need we? As Judge Everly said just now, it was an unconditional gamble. The stakes go by the figure, and the 'high field' scoops the pool."

There followed a shout of applause and laughter, for Mr Beck's exposure was complete. The Colonel and the Judge cut very sorry figures, as, self-confessed swindlers, they sneaked out of the room. All were delighted at the neat way in which the tricksters had been caught in their own trap.

"There only remains," went on Mr Beck, suavely, "to pay over the cash to Mr Eyre—or rather, if he will allow me, to his wife, who has kindly promised me a receipt in full."

Kitty, who had listened delightedly to the rogues' discomfiture, started at the sound of her own name, looked up and met the challenge in his eyes, and remembered her promise of the night before.

Blushing and smiling, she flashed back her answer to the challenge, and said saucily, in her dainty drawl:

"Sure."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.