RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

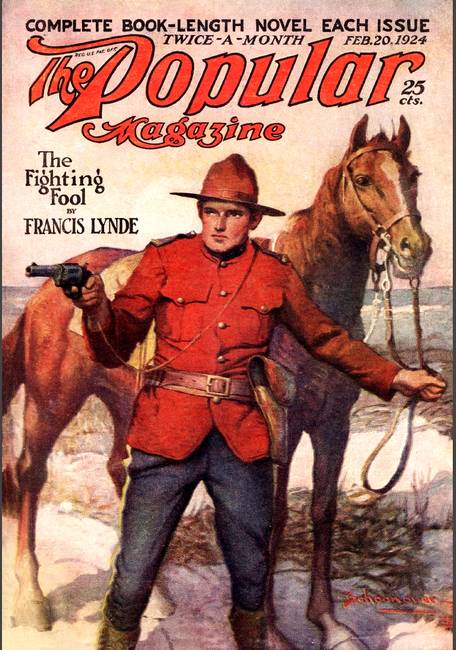

The Popular Magazine, 20 Feb 1924, with "The Iron Chest of Giovanni the Grand"

James Francis Dwyer

JAMES FRANCIS DWYER (1874-1952) was an Australian writer. Born in Camden Park, New South Wales, Dwyer worked as a postal assistant until he was convicted in a scheme to make fraudulent postal orders and sentenced to seven years imprisonment in 1899. In prison, Dwyer began writing, and with the help of another inmate and a prison guard, had his work published in The Bulletin. After completing his sentence, he relocated to London and then New York, where he established a successful career as a writer of short stories and novels. Dwyer later moved to France, where he wrote his autobiography, Leg-Irons on Wings, in 1949. Dwyer wrote over 1,000 short stories during his career, and was the first Australian-born person to become a millionaire from writing. —Wikipedia

In ancient Florence Robert Henry Blane answers the lure

of an

old love and saves a family tree from the blight of destitution.

IN the lobby of the Hotel Miramare at Genoa sat Robert Henry Blane, the handsome adventurer from Houston, Texas, known in many cities as The Texan Wasp. Mr. Blane was amused. The conductor of a touring party, a lean, bad-tempered man, full of that vicious intensity and driving capacity that a tour conductor must possess, was rounding up his leg-weary victims. He herded them together in the center of the lobby, jerking out instructions regarding trains and baggage, counting them at intervals as if they were so many sheep that he, a hard-faced human collie, had to guard.

Mr. Blane, watching the fellow, thought of the song of the tour conductor that begins:

You longed to roam from your cozy home.

You bragged of your wanderlust;

You studied the map like a crazy yap,

Now you'll travel, by gosh, or bust!

A perspiring fat woman seized a moment when the tour conductor's eyes were off her and moved fearfully to a small table near which The Wasp was sitting. Hurriedly she emptied the pockets of her big traveling coat of catalogues that she had collected in the mad rush through Italy. Catalogues of museums and picture galleries, printed descriptions of monuments, a torn, week-old copy of an English weekly newspaper printed in Italy.

The fat tourist found the eyes of Robert Henry Blane upon her and stammered an excuse for unloading. "They're so heavy," she murmured apologetically. "And they're not a bit of good to me."

The tour conductor sprang upon the fat lady and dragged her back to the group.

Robert Henry Blane stretched out his long legs, lit one of his favorite cigars made from fine Algerian tobacco, then, from idle curiosity, reached out an arm and picked up the torn copy of the newspaper that the fat lady from Moline had thrown upon the table. He glanced listlessly at the headings. There was the perennial "List of British and American Residents in Florence," the "Weekly London Letter," "Church News," "Cab Fares in Florence and the Suburbs," "Doings at the Galleries," and all the other futile and noninformative matter which the editor of a sheet in a town where nothing happens is forced to use in making up his paper.

The Texan Wasp was on the point of tossing it back upon the table when a name sprang from a column headed "Movements in Society." A name that thrilled him. A name that hurled itself from the page and cuddled down in little mental arms that reached out for it. Soft little arms of memory that had longed to embrace it.

For an instant Robert Henry Blane was unable to read the encompassing paragraph. The printed name stunned him, then love-famished eyes fell upon the few lines. Again and again he read the little announcement. It ran:

The Comtesse de Chambón and her niece. Miss Betty Allerton, of Boston, U.S.A., have arrived in Florence and are staying with friends of the comtesse on the Lungarno Amerigo Vespucci.

For a second Robert Henry Blane remained immovable, then he tossed the paper from him and sprang to the desk of the pompous concierge. "When is the next train for Pisa, with connections for Florence?" he cried.

"In fifteen minutes," answered the gold-laced one. "It will be the Rome Express and you will change—"

"My bill! Quick!" interrupted The Wasp. "Get my baggage down! Room 281 Hustle!"

A startled bookkeeper fumbled with figures, and the tall Texan cursed the intricacies that surround hotel bills in the Italy of to-day. The fellow protested nervously. "I must calculate the taxes," he whined. "On the total go the special taxes. They must be added. It is the law."

"Confound the law!" roared The Wasp.

The frightened bookkeeper wrestled with the different taxes—tourist, de luxe, tax for the mutilated, tax for sojourn and service—that make the traveler's days unhappy ones, and, at last, from the welter of figures he built a total. The grips had been brought down with much rushing and wrestling. A taxi had been found.

Robert Henry Blane looked at his watch. "Fifty lire if you break all records to the station!" he cried to the chauffeur. "Let her go!"

Through the two-score tunnels that make the ride from Genoa to Spezia recall memories of New York subways! On and on to Pisa, whose Leaning Tower, visible from the train, has grinned at the laws of gravity for nearly six hundred years.

The Wasp changed at Pisa, and, during the little wait for the Florence train, he asked himself the reason for his mad rush. Would Betty Allerton be pleased at meeting a tall adventurer from Houston whose deeds had made strange gossip in all the capitals of Europe? Would she wish to speak to a man whose doings had the same relationship to honorable life as the Leaning Tower had to the well-plumbed buildings of to-day? Modesty sprang upon him and tore the little dreams to pieces.

On and on swept the train, The Wasp a little despondent. The great man hunter, No. 37, had spoken once of the Law of Compensation that rules the world, and his words came back to Robert Henry Blane. A paraphrase of Emerson who told how Crime and Punishment grew on the one stalk so that the hand that plucked the one assuredly plucked the other. The Wasp damned the theory. He told himself that it was not true, and he was still trying to believe it wrong when the train roared into the city of the Medici, the city of Cosimo the Grand and Lorenzo the Magnificent! The City of Art and Poetry!

On the open piazza in the center of the Ponte Vecchio, that

strange bridge of shops that spans the Arno, stood The Texan

Wasp. Mr. Blane was not in a good humor. Somewhere in the

sweet and wonderful city of Florence was a person he wished to

see, yet that person was, for the moment, unfindable.

The tall American had visited the office of the newspaper in whose pages the little paragraph announcing the arrival of Betty Allerton and her aunt had appeared. The editor was sympathetic but helpless. He had gathered the item from some source that he had forgotten, and he regretted exceedingly that he could not tell his distinguished visitor where Miss Allerton was located.

Robert Henry Blane had walked the Lungarno Amerigo Vespucci at every hour of the day. He had spent hours staring into the windows of its art shops where the hastily painted copies of the fat-jowled "La Gioconda" wait for purchasers. And with each moment that went by the belief that he would come face to face with the girl he loved was slowly dying. Florence seemed a city without a soul; a dead city because Betty Allerton was not there.

And then, on this third morning after his arrival in the city of Cosimo, something happened to stir the dead monotony of the days. As The Wasp stood upon the little open place in the middle of the Ponte Vecchio a beggar, whose feet had been carefully twisted in childhood so that he could earn a living without work, separated himself from the stream that passed between the little shops of the jewelers and crawled onto the open space beside Robert Henry Blane. A queer beggar. His nether portions rested on a soap box to which were fixed four little wheels, and he propelled this box by leaning forward and clawing at the roadway with two iron hooks.

He halted the soap-box chariot close to The Wasp, and, with the iron hook held in his right hand, he began to scratch the dusty roadway. His queer, contorted face was upturned. Cunning, pain-smeared eyes endeavored to get the attention of the handsome Texan.

Robert Henry Blane glanced at what the fellow was doing. The cripple showed delight at getting the tall American's eye. Hurriedly he scratched the title "Signor" in the dust, then, to the surprise of the Texan, he scrawled after it the word "Blane." For a few seconds he allowed his handiwork to remain, then hurriedly rubbed it out as if fearful that it would be visible to the passers-by.

The Wasp moved closer to the soapbox chariot. He leaned down so that he could speak to the deformed thing on the ground and put a question in Italian. "How do you know my name?"

"Kavados the Greek told it to me, signor," answered the cripple.

The ears of The Wasp conveyed the name "Kavados" to his brain, and the brain went questing. It flung up a picture of a small street running off the Faubourg Poissonière in Paris, a little street called the Rue de Dunkerque, and in a filthy house in the little street sat a spider. An extraordinary spider. He sat in a gloomy room on the first floor, and it was whispered among the people who had dealings with him that he knew of things that happened in far-away places long before the newspapers spread the information to the people on the street. He was a Greek from the slopes above Corinth, where the little grapes that become raisins ripen in the sunshine, and, like many another wanderer:

True patriot he, for be it understood

He left his country for his country's good.

Robert Henry Blane was not pleased at the remembrance of his dealings with Kavados the Greek. The fellow had bred a queer dislike in the mind of the Texan. There was something about him that seemed unearthly, something that savored of black art. He was a dank person who seemed to bear a strange relationship to that slimy, many-tentacled family of cephalopods that throttle and choke their prey with their dreadful feelers. .

The Wasp put another question. "Why did Kavados the Greek tell you my name?" he demanded.

"He wishes to see you, signor."

"How did he know I was in Florence?"

"Yesterday he saw you on the Lungarno. He drives each day in a closed carriage, signor. He looks from a little hole that is cut in the blind and he sees everything. Everything that happens."

"And where am I to see him?"

"In the Via di San Gallo. I am to show you the way, signor. Pardon me a little. I have forgotten. He told me to bow myself before you because you were an illustrious American. It is difficult for me to do so because you stand above me as the Duomo stands above the kennel of a hound. Pardon."

The Texan Wasp considered the sly and smooth-spoken occupant of the soap box. The Wasp was a little annoyed. The fact that a person in a side street of Florence—a person whose affairs were strange and mysterious—had sent a beggar to arrange a meeting with him was not pleasing. The name "Kavados the Greek" did not stand for Romance. It stood for trickery, intrigue and deviltry, and, for the moment, Robert Henry Blane had no longing for such matters. He craved Romance, soft, sweet Romance such as should be found in the old, old streets of Florence through which, in the colorful days, Lorenzo the Magnificent took his daily walk with his following of artists and poets.

"What is the business that Kavados wishes to discuss with me?" snapped the Texan.

"Ah, signor, if I knew I would be wiser than the three judges." answered the cripple. "All I know is that he wishes to see you at his place. It must be important because he pays me all that I could beg, and, as the English and Americans are many at this season my charge will be high."

The Wasp smiled. "Go ahead," he ordered. "I'll keep your chariot in sight."

Kavados the Greek had a face that looked as if it had been used as a scribbling block by a legion of devils. Every known hieroglyphic of vice had been etched on it. Sin had crept over it, crossing and recrossing, leaving little marks like those left by the feet of the stinging centipedes of Brazil. There was no necessity for the evidence of a recording angel when Kavados stood up in the Big Circuit. Like one of those engines that records its speed, its stops, and direction on its own indicator, the face of the Greek had written upon it an autobiography that was a little terrifying.

The eyes had retreated as if fearful of the things they might suddenly see. The mouth had tightened lest a word might drop from it in an unguarded moment—a word that might be twisted into a hempen rope that would swing Kavados into the next world. And, although the present world was annoying at times to the Greek, he had a tremendous fear of the one to follow. On the slopes above Corinth, where he was born, the clergy took a keen delight in picturing the torments of the other world to the children of the raisin growers, and the vision that the young Kavados had formed of those torments had never quite been obliterated. Sometimes he cursed the clergy for their dreadful capacity in picturing punishment in places that they had never visited.

Obsequious and smirking he was before Robert Henry Blane. His home was honored. His poor home, which was not a home but a refuge from the world, was too mean for a person like Monsieur Blane to visit.

With his skinny hands he brushed the big brocade chair on which he invited his visitor to rest. It was a chair, so he gabbled, that had rested the legs of the great. Some said that Savonarola had sat in it. He didn't know. It had come to him in queer ways and its history could not be traced. He had many things that were precious. The house was a museum. At times, so he chattered, he was afraid. He lived alone and there were murderers in Florence. Many of them.

The Wasp smiled. Kavados the Greek, who had popularized murder, was beginning to grow afraid for his life.

The Greek suggested refreshments. He remarked that he had a wine more wonderful than the finest and silkiest Lachryma Christi. A wine that could not be purchased in the open market. It was deftly smuggled so that the liquor tax would not spoil its flavor. Did the illustrious signor know that a revenue tax spoiled a wine?

"I will not drink," said The Wasp, interrupting the babbling Kavados. "What is it you wish to discuss with me?"

"Just a sip," pleaded the Greek. "It is so very—"

"Not a sip," snapped the American. "Come to business."

Kavados crept close to the big American. Fear—a queer, sickly fear—was enthroned within the fellow's eyes. He looked around him continuously. The old house that, in the days of the Medici, had been the palace of "a Florentine noble, seemed to be waiting for some confession that he wished to make. The Texan Wasp felt that the evil deeds of the Greek were riding hard on his heels; that the ghosts of men that he had robbed and ruined were waiting in the shadows of the big rooms to throw a lariat around his feet when the moment came.

"It is a strange story," began Kavados, "but you have heard strange stories before." He tried to laugh but the effort was not successful.

"There was an affair in Brussels in which you took a part, Signor Blane," he went on, "and this matter of mine has some points in common with it. I mean the affair of The House in—"

"We won't discuss my affairs," interrupted Robert Henry Blane. "Let's keep to your matter. What I do or do not do has no concern with you. Tell me what you want of me."

The sickly grin widened. The long, lean hands of the Greek writhed around each other as if seeking sympathy. He swallowed spasmodically.

"It is this, then," whispered Kavados. "I have got something that I am afraid of. Something that has come to me by strange ways. Say that I bought it, that I stole it, that I found it on the street. Say anything that you like. The point is that I have it and I do not know what to do with it. Listen, I am afraid of it! Terribly afraid of it. But I must see what is in it. Here in this town I am a Greek, and the Italians do not love the Greeks. I am a recluse, and I know few. I mean I know few that I would trust. That is why I sent for you. I saw you on the Lungarno and I thought you would be the person that I needed. I know that you have no fear."

He paused, wiped the cold perspiration from his face and looked at The Texan Wasp. "The price is anything that you wish," he murmured. "I am rich. I can tell you that I am rich because—because the Signor Blanc is a gentleman. The money is here in the house to pay you when the work is done."

"And what is the mysterious job?" questioned The Wasp.

"Come with me," whispered the Greek.

He stood up and turned to a door in the rear. The Wasp followed him. The statement of Kavados seemed to have increased the mystery of the place. In the big rooms was a sort of cold fear, a grimy terror that detested the sunshine and the fresh air.

The Greek led the way through a long corridor, a corridor that in the days of the Medici must have been splendid in its gilt and colors but which was now a damp and evil-smelling place. The two reached a thick nail-studded door which Kavados opened with a large key.

"Wait," said the Greek. "We must have a light. Be careful. There are steps here that lead down to the cellars."

The trickster from Corinth lit a lamp and preceded The Wasp down the stairs. The American had little interest in the business, but the fact that he had spent uneventful days in the city by the Arno made him inclined toward any adventure that might relieve the monotony.

Kavados stopped at the bottom of the stairway, stood for a moment as if listening, then led the way across the floor of large tiles—tiles whose green coloring had been extracted by the damp of the ages. The place was dark, but the lamp seemed to give a feeling of confidence to the Greek.

In the center of the large basement room he paused before a heavy-legged table—a table such as one might have found in the refectory of an old monastery; a long table whose boards were of black mahogany, and whose legs looked as if they could hold up all the necessaries for a million banquets of the old gorging years that seem so far distant from our days of quick lunches and our eternal chatter of vitamins and proteids.

Upon the table rested something large that was covered by a heavy rug. A huge thing that bulked under the covering like a small coffin. The Greek put out a thin paw, tore the rug quickly aside, and held the lamp high so that the American would have a good view of the object.

It was an iron box of a type that Robert Henry Blane had never seen. An iron box such as youngsters might dream of as the receptacle of pirate treasure. An iron box such as Tamerlane might have used to carry the most precious objects of the gorgeous plunder his elephants dragged from Persia to golden Samarkand!

An astounding box! A box of hammered iron with girdles of brass! A box that raised visions of fat dead coins—dropsical golden pieces that had been captured and stored by strong-armed robbers. A squat thing that had a bulldog look about it, a threatening, truculent look that was quite sufficient to make the nervous investigator pause. It carried the impress of big days, days when things were made to last. It had rolled through the centuries knowing no age, no period. It had the queer quality of eternal life that at times is a little revolting when compared with fleeting human existence.

Kavados the Greek lifted the lamp higher. The light splattered on the brass girdles of the box, on the polished corners of it, on an inscription that ran along the great lid.

"Do you know German?" he asked.

Robert Henry Blane stepped closer and looked at the words of brass that had been welded onto the iron. Translated into English the German inscription ran:

### SIGN

The god of vengeance acts in silence.

The voice of the Greek was a thin thread of fear that came tremulously to the cars of the big American. "This is the work that I want you to do," he murmured. "I want you to open it. I—I am afraid of the thing. Open it and I will pay your price!"

Robert Henry Blane took his eyes from the iron box and

studied the face of Kavados the Greek. The fear that was upon

the fellow had brought out further traces of hidden infamies.

Terror had acted like one of those chemicals that, poured

upon lettering that is nearly invisible, brings the script

miraculously to view.

The big American's curiosity was stirred. What was in the great iron box? What precious thing did it hide? The face of the Greek expressed a terror that was a little disgusting in its nakedness, a fear that was revolting. Yet, struggling with the terror, combating it, snarling for its share like a hungry hound, was a chattering curiosity, a longing to see, to know, to find out, that really defeated the great dread.

The Wasp smiled. "It has got your nerve," he said quietly.

The Greek moistened his dry lips. "Yes, yes," he admitted. "I am—I am afraid of it."

"What do you think is in it?" questioned the American. "Have you any idea?"

"None! No, no, I have made no guesses!"

"But you have been led to believe that there is something wonderful inside?" persisted Robert Henry Blane. "Some one has told you things?"

"No, no, I swear I know nothing," stammered Kavados.

The Wasp put his right hand on the iron box and the frightened Greek stepped backward as if he feared some uncanny happening. There seemed a possibility of his dropping the lamp. Blane took the light from him and placed it on the table.

The big American walked around the iron mystery. The huge lid fitted down tight, showing only a slight cranny at the junction line; the hinges were invisible, and from the preliminary survey there was only one spot on the iron hide of the thing that suggested a possibility of opening it.

This spot held the attention of The Wasp. It was a circular depression, some four inches deep and some two inches in diameter, and it looked to be the point upon which the attack should concentrate. Robert Henry Blane held the lamp close and examined it. There was no keyhole at the bottom of the depression as he thought there might be, but, instead, there were five characters in the form of a circle. They looked to be flourished letters of the German alphabet, each encircled by a little ridge of brass.

The Wasp pointed to the opening and addressed Kavados. "I think the secret is here," he said. "Possibly a trick combination. Have you tried?"

"No, no." stammered the Greek. "I have done nothing."

Blane grinned. He was on the point of thrusting the finger of his right hand into the depression with a view to testing carelessly the result of pressure upon the characters, but he suddenly reconsidered the advisability of doing anything of a hasty nature with the mystery box. He stooped, picked up a short stout stick from the floor, inserted it in the opening and pushed one of the characters.

The effect was startling to Robert Henry Blane. The pressure on the characters brought forth a surprising happening. From the side of the hole, at the bottom of which the characters lay, there flashed out a circular blade that cut with amazing ease through the stick and disappeared again, leaving the severed piece in the depression.

The Wasp turned upon the Greek. The gray eyes of the angry Texan fell upon the shivering form of Kavados, and Kavados came to the sudden belief that the basement was not a healthy spot. He snatched the lamp and made a rush for the stairs leading to the first floor; a little squeal of terror came from him as he fled. The anger stirred in the big American was too much to combat after the nervous strain.

The Wasp stood for a moment beside the iron box, his face turned to the flying Greek upon whom terror had pounced. The big American was on the point of ordering the fellow to return with the light, but the order was throttled by an unexpected happening. From the head of the steps down which Kavados and Robert Henry Blane had descended into the cellar there came a quick flash, the hard noise of a shot echoed through the cellar, the lamp in the Greek's hand crashed to the floor, and Kavados went down with it.

The cellar was in darkness, complete and absolute darkness. Not a pin point of light came into the place. The walls of heavy masonry were unpierced by windows, the nail-studded door at the head of the steps evidently was closed.

Blane, catlike and alert, moved from the table. He was uncertain whether his presence in the cellar was known to the person who had fired the shot that had bowled over the Greek, but he was determined to take no chances. With noiseless feet he moved toward the rear of the cellar, in the opposite direction to that in which Kavados had been moving when knocked over by the shot.

The scratch of a match came from the head of the stairs, a whispered curse as it failed to strike. Another scratch, then the tiny flame showed high up in the surrounding darkness. The Wasp watched it. It began to descend. The American made out an uplifted arm, the side of a bald head, then another face, lean and ratlike, thrust forward, searching the sea of darkness with questing eyes.

The match died out. Another took its place. Another still. The two descending the stairs were moving cautiously. They were evidently anxious about the condition of Kavados. The odor of kerosene from the broken lamp filled the cellar.

They found the Greek. The match was lowered, waved above him. The dull sound of a shoe thrust hard against a body came to The Wasp. The two laughed, then advanced toward the table upon which was the iron box.

The Wasp came to the conclusion that his presence in the cellar was unknown to the pair. They evidently had reached the door at the head of the stairs at the moment the Greek had decided to fly from the anger of the American, so they had heard nothing to make them believe that another person was in the basement.

Blane listened. Scraps of whispered conversation came to his ears. They reached the table. The match was lifted, then a stream of blasphemous exclamations expressing pleasure and surprise came from the two. The iron box that carried the admonition concerning the god of vengeance was made plain to them.

Their words were throaty with excitement. They gasped and gurgled. They cursed softly to express their delight. They called in profane language to the whole calendar of saints, urging the holy ones to look with wonder eyes upon their find. There was something childlike and ludicrous about the stream of impious language which they unloosed in the delirium of joy that came upon them when their eyes fell upon the iron chest.

An interval of darkness came as a match burned out. One of the two stumbled back to the place where the Greek had fallen. The ears of the Texan heard crunching of glass and understood. The fellow was dragging the wick from the shattered lamp.

The wick made a fine light, a light that was hailed with more joyful profanity. It lit up the table and the box; it fought with the encompassing darkness. Blane moved farther into the gloom. The voices of the two blended into a soft, slobbering drool. They evidently were beside themselves with delight.

There was an argument concerning weight, the possibility of moving the thing. It was put aside hurriedly. Moving it was out of the question. The wick flared up like a torch. It moved around the box as the two sought a method of opening it.

The flame halted, dropped lower. The two heads were thrust together. Into the chatter came a tense note. They had located the depression, at the bottom of which were the five flourished characters, each surrounded by a ridge of brass.

The Wasp held his breath. There was a silence in the cellar, a soft, quivering silence that seemed to realize its own evanescence.

And the noise that the silence seemed to fear came with appalling suddenness. It was a howl of pain and fear that filled the cellar, crashing through the darkness in a manner that seemed to illuminate it. A dreadful howl. It might have been uttered by some prehistoric animal trapped by the cunning of a cave man.

The howl was followed by curses and inquiries. The lamp wick was dropped and trampled on. From the darkness came whimpers of pain, pleadings for quiet, blasphemy that reached a plane that made it really artistic.

Blane listened. More matches fought with the darkness, the wick was found and relighted. There was a remark concerning the possibility of poison, then more yelps of fear. The Italian mind of the injured one had pounced on a further horror connected with the injury. He surmised that the medieval mechanic who had planned the infernal mechanism that slashed the inquisitive finger thrust into the depression, had made his device more deadly still by poisoning the blade. A terrifying thought!

The uninjured man fought the belief of his friend. Fought it unavailingly. Dread of a quick death in the darkness by methods that the brain of a Borgia might have originated killed for the moment all interest in the iron box and its contents. The fellow staggered toward the stairs, his companion following him. They clumped up the steps, stumbled through the nail-studded door, and The Wasp listened to their footsteps as they went along the corridor through which he, Blane, had followed Kavados. The whole time of the visit had not exceeded ten minutes, and the startlingly dramatic quality of the happening left the American breathless.

The Wasp moved across the cellar, struck a match and located the Greek. He stooped and made a quick examination. The revolver bullet had struck Kavados high up on the right shoulder, making a nasty and dangerous wound. He had lost blood, a great quantity of blood.

Robert Henry Blane lifted the Greek in his strong arms and carried him up the stairs and through the long corridor to the big room in which they had talked. Mr. Blane was a little puzzled as to what he should do with the fellow. The Greek lived alone and it would be difficult to get in outside help. The Wasp cursed his own childish curiosity that had brought him into the idiotic tangle. The fact that he could not locate Miss Betty Allerton had brought to him an ennui that had made him an easy victim of the Greek's note.

Kavados came out of the swoon into which he had slipped. The Wasp found a small bottle of cognac and forced some of it between the trickster's lips. He questioned him as to what he should do.

"You should have a doctor at once," suggested Blane. "Possibly the hospital is the best place for you. Do you understand? The hospital." The Greek nodded feebly. "Do you prefer the hospital?" questioned The Wasp.

"Yes," he gasped. "The Hospital of Santa Maria. My name will be—will be Calimara. Understand?"

The Wasp rushed out upon the Via di San Gallo. A lane ran beside the house, connecting San Gallo with the Via San Reparata. The lane was deserted. Blane considered the passage as a means of covering his tracks so that the police could not locate the house of Kavados by interrogating the cabman who drove them to the hospital. He ran back into the house, picked the Greek up in his strong arms, and carried him swiftly along the passage into the Via Reparata. An empty one-horse carriage turned a corner, the Texan hailed it, placed the Greek on the seat and drove off.

Kavados muttered during moments of consciousness. "Don't forget name—Calimara—Signor Calimara. And I—and I have no address. Found me on the street."

"As you say," said The Wasp.

They reached the hospital and Robert Henry Blane carried out the wishes of the tricky Greek. He stated that he had found a man on the street, badly injured. The man said his name was Calimara and he desired to be driven to the Hospital of Santa Maria. That was all.

"And your name?" questioned the receiving medico.

"Mine?" said The Wasp. "Oh, mine is Blane. Robert Henry Blane. Address? Well, I have none in particular. I'm leaving Florence this afternoon. Put my address down as care of Barclay's Bank, Paris."

The medico hesitated. He muttered something of police complications, and then the polite and affable person before him was suddenly replaced by an arrogant and domineering double. The doctor was appalled. He cringed before the gray eyes of the handsome Texan.

"I have nothing to do with this filthy matter," said The Wasp. "I have been kind enough to bring a wounded man to your institution. I have given my name and address. I wish you good day."

The Wasp found a taxicab and drove back to the Piazza Vittorio Emmanuele. He was a very angry and discontented person. The affair of Kavados had stirred his temper, and, mentally, he consigned the Greek to a spot much more distant than the Hospital of Santa Maria.

He dismissed the cab on the Piazza and walked aimlessly along the Via Strozzi till he reached the corner of the Via Tornabuoni. And there, by the Palazzo Strozzi beneath the monster corner lantern and the iron link holders that put our present-day work to shame, the bustling street became, like that wonderfully alley in Bagdad, a place where dreams come true!

Robert Henry Blane found himself talking to some one whose presence made him forget everything but the fact that she was there before him on the crowded pavement. Golden words, minted of throbbing emotion, sprang to his lips. The little sunbeams plaited themselves in the meshes of her soft hair and made a golden aureole for her. Her lips had the redness of hollyhocks surprised by the dawn!

The hurrying crowds were blotted out. Kavados and the great iron chest were dropped into a limbo of forgetfulness. The bustling corner of the Via Tornabuoni and the Via Strozzi became an open gate to paradise. Betty Allerton—a Betty Allerton more charming than even Blane's dreams had pictured her—was talking to the tall adventurer from Houston, Texas! Actually talking to him!

She seemed delighted to see him. He felt sure that she was. She flung questions at him. Why was he in Florence? Did he know that she was there? How did he find out? When? Where? How long was he going to stay?

She didn't wait for replies. Her questions were little explosive remarks bred of sudden happiness. They had not seen each other since the night at the Villa Kairouan at Algiers when Robert Henry Blane had played peekaboo with the great man hunter, No. 37.

Hours later, when The Wasp reviewed the thrilling encounter, he wondered if he had suggested the walk along the river. He told himself, with a little gasp of surprise at his own impudence, that he must have put forward the idea, and he marveled at his boldness. But Betty Allerton had made no objection. Side by side they walked down to the Arno, the broad, yellow Arno that flows by the City of Lorenzo the Magnificent. The sun was dropping down toward Bellosguardo and the old houses along the Lungarno were tinted golden by the afternoon rays. The Ponte Vecchio was a fairy bridge that an imaginative artist might paint to illustrate a story that he loved. Boys sat on the century-whittled parapet and fished for gudgeons who were too busy enjoying the afternoon to bother about the hooks baited for them.

They passed the weir over which the hurrying waters thundered. They wandered on and on. A gypsy girl with a strange green mole on her cheek and with great hoop earrings of gold that rested on her shoulders, was playing a guitar softly by the river wall. The wench curtsied low before Betty Allerton and The Wasp paid for the curtsy with a handful of coins.

"Isn't she romantic?" murmured Betty.

"Who? Where?" stammered Robert Henry Blane. "I—I didn't look at her. Pardon."

Miss Allerton smiled softly as she glanced up into the handsome face of The Wasp. He could see nothing. He could remember nothing. Kavados the Greek and his iron chest that had the trick lock were as lost to him as the history dates that he had learned at college.

Had she been to America? To Boston? To New York?

"Yes, yes," cried Betty. "I spent a month in Boston! A wonderful month! It was beautiful! I motored out every day to places that I loved! No, no, it hasn't altered. Boston is like Florence. It goes along in its old-fashioned way and grows older and cosier with the years."

"And New York?" questioned Blane.

"For three days only," answered the girl. "A delirious three days. Plays and parties. When I got to the boat I slept for twenty-four hours although we ran into a gale. I wanted to stay longer. I wanted to go West, but—but auntie wanted to get here. I didn't know why, not then, but now I know."

A little touch of sadness came into her voice, and the Texan noted that the light left her wonderful eyes. He longed to know the reason.

"Is—is something wrong?" he asked.

The girl looked straight ahead and disregarded the question.

"Is there anything that I could do?" continued Blane. "Anything at all?"

Betty Allerton glanced up at the tall, handsome adventurer at her side. She told herself that there was no man in Florence as good looking as Robert Henry Blane. She sighed softly, then spoke.

"You have a habit of doing—doing reckless things," she said haltingly. "I am wondering if you would do something for me?"

"Anything!" cried The Wasp. "Anything at all! Do you—do you want me to kill some one?"

Betty laughed nervously. "I wouldn't like you to kill him," she said softly, "but if he could be wetted a little! I mean if he could be thrown into the river and then taken out again I would be pleased. Do you remember a fat youth you capsized into Lake Kezar? I will never forget how he spluttered when he came to the surface."

"Tell me who is the man?" cried The Wasp. "Tell me his name?"

"He is some one that Aunt Diana is trying to marry me to," said the girl softly. "It's really not his fault altogether. Aunt Diana is nearly as bad. Nearly. You see he has a title. He—he is a count, and Aunt Di thinks—thinks that—"

Miss Allerton broke off abruptly. She had glanced up at the man at her side and the look upon the face of Robert Henry Blane choked back the little confession that she had begun. In the gray eyes of the Texan there was a look that did not bode well for the person seeking the hand of the girl. The scar upon his jaw showed like a white line in the tan. She was startled, amazed, a little terrified.

Bravely she tried to counteract the flame she had stirred by her words. "It is nothing," she stammered. "I was joking and you have taken me seriously."

"But you spoke as if some one were forcing you," cried Blane. "If some Italian count is annoying you—"

"No, no, no!" protested the girl. "Please forget what I said. Please do! Now, it is all forgotten, isn't it? Just say that you didn't know what I was talking about."

Robert Henry Blane's face lightened but he wouldn't admit that he had forgotten. The little confession had upset his temper. He understood the title-hunting aunts that are ready to sell nieces who are heiresses to small European persons with empty heads and empty pockets.

The sun slipped behind the hills, and the quiet of the Cascine, the park laid out by the pleasure-loving Medici, held them in a strange enchanted spell. Robert Henry Blane wished to talk, but he could not. There were a thousand things that he wanted to ask the girl who had believed in him in the long ago; the girl who thought he might climb to wonderful heights and do great things. But the courage of the Texan failed him whenever he made an attempt to express himself. The nerve that had made him a reputation among men who knew little of fear was routed by the presence of the girl. They sat together and looked at the wagons upon which the reapers were stacking great piles of the new-mown grass. The memory of golden days came up before them and speech became difficult.

Blane thought how unworthy he was to sit in her presence. He wondered what she would have thought of the happening of the morning in the cellar beneath the house of Kavados the Greek. Kavados who had picked the Texan for the job of opening the iron chest because he thought him an adventurer who knew no fear. Three times he nerved himself to ask the name of the Italian count to whom Aunt Diana was intent on marrying Betty, three times he failed.

"I must go," said Betty. "I have an appointment with auntie. I am to meet her at Pellini's."

They held hands for a long moment at parting. Robert Henry Blane tried again to speak, but words would not come.

Back to his hotel went The Texan Wasp. A rather depressed

Wasp. Away from Betty Allerton the world was dark and dismal.

Florence was now an ordinary town with little to differentiate

it from a lumber camp on a wet day. So thought the big

Texan.

He paused on the landing before the door of his room. A queer sense of impending danger came to him. For a few seconds he stood undecided, then his strong hand turned the handle and he entered.

Three men acted as if the scene had been well rehearsed beforehand. Two, one on either side of the door, stepped between the opening and the incoming American, the other, hand thrust hard into a loose coat pocket, stepped close to him. The third person was evidently the person in whom authority rested.

"Signor Blane?" he murmured.

"Quite correct," answered The Wasp. "And what, may I ask, are you doing in my room?"

The big American spoke in Italian, with an accent so perfect that a little look of amazement passed over the face of his questioner. "You are an American, signor?" he said.

"I believe so," snapped The Wasp. "But answer my question before you put any others. What are you doing in my room?"

"It is this," said the man. "To-day you carried to the Hospital of Santa Maria a man who was wounded. A man who said that his name is Calimara. We are of the secret police. We do not think his name is Calimara. We are also doubtful about where you found him. You said that you found him on the street?"

"Correct."

"We doubt it, signor."

"You are welcome to your doubts, but not to my room. Don't you think a little fresh air would do you good? Wouldn't it be a good idea if the three of you took a turn around the block?"

His coolness amazed the trio. They, brought up in the Italian school of emotional explosiveness, were a trifle astounded.

"But signor," protested the leader, "we are of the secret police. Do you understand? This man who says his name is Calimara is a person under suspicion. We wish to know where you found him?"

"And I have told you."

"But it is not true."

The gray eyes of the Texan hardened. The slight scar showed white and menacing. Hands that were wonderfully made, inasmuch as they carried the greatest possible strength as well as elegance, bunched themselves quickly into fists.

The leader of the intruding police saw the movement and took a quick step backward. The hand thrust into his coat pocket brought an automatic into view. "Be quiet, signor," he commanded. "I have but told you of our suspicions. We wish the address of the man you brought to the hospital?"

"I do not know his address."

"Listen," said the officer. "His name is Kavados and he is a Greek. See, we know a little. Does that help your memory?"

"Not at all."

"Then listen again. Possibly you may know something of this. Kavados had in his possession an iron chest whose worth cannot be measured. It must be regained immediately. That is why we have waited here for you. We have waited three hours, signor."

"I have nothing to tell," said The Wasp. "Nothing."

"Then you must come with us. You are under arrest."

Into the mind of Robert Henry Blane came a fear-screened picture of an arrest, of slow Italian court procedure, of possible imprisonment. He saw the bleak reports of the case in the English paper printed in Italy, wedged in with the "Church News," the "Gallery Notes," "Cab Fares in Florence and the Suburbs." It would be a tremendous find to the editor. And Betty Allerton and her aunt would read the scurrilous stuff!

The Wasp took a step toward the window and made a signal to the leader of the police. The fellow followed him. His two companions remained beside the door.

The Grand Hotel occupied a corner of the Piazza Manin, and the room of The Texan Wasp was on the angle made by the little Via Montebello as it entered the Piazza. To the right ran the Arno; to the left the packed, old houses toward Santa Maria Novella and the Stazione Centrale.

"I'm going to tell you where I found him," said the American. "From the window here I can show you his house."

"His house?" repeated the officer.

"Sure. I took him from his house. I'll show it to you. You can see it from here."

The Wasp leaned out; the alert, black-eyed secret officer stood beside him. Robert Henry Blane scanned the street while pretending that he was making an effort to locate a house in the huddle toward the east. Down the Via Montebello from the direction of the Caserne came a swiftly moving wagon piled high with green grass. Blane recognized it as the wagon that was gathering up the new-mown hay in the park as he and Betty walked together. A strange flood of sentimental memories rushed over him. Thoughts of Boston, of New York, of Texas. He pulled himself together. What did the little fool beside him want? Ah, yes! He wished to find the house where Kavados the Greek lived. Yes, yes. The house was in the Via di San Gallo, a mile away from the Grand Hotel, but that didn't matter. Any house would fit the bill.

"See!" cried The Wasp. "See that house with the high, red roof? No, no, to the right!"

The beady eyes of the officer sought to find the building to which the big American pointed. The Wasp took a quick glance at the wagon that carried the piled hay. A great bed of hay. It reared itself up from the wagon, a mattress for a giant. The sweet odor of it went out and filled the street. Again came thoughts of Betty Allerton—Betty whose plotting aunt was endeavoring to marry her to the penniless scion of a Florentine family whose genealogical tree was all that he could boast of.

The little officer was speaking. "Keep your hand steady," he ordered. "One minute you point to one house and the next minute you point to another. Will you—"

His remarks were interrupted. The wagon was directly beneath them. The Texan Wasp, with one thrust of his strong arm brushed the officer from the window, then, with a swift glance at the moving wagon he sprang! Sprang through the open window into space! Beneath him was a mattress of green grass, piled feet high, a mattress that Betty Allerton had looked at with wonder, a mattress that was made to break his fall!

He landed on it! Landed squarely in the center of the great bed of grass! Landed with a thump that shook the wagon and startled the horse! Clawing for a grip on the slippery bed he glanced upward. The little officer was at the window. His arm went up, the crack of an automatic pounced on the soft noises of the street.

The bullet seared the rump of the horse. Startled, the animal sprang forward, nearly jerking from his seat the driver who had stood up in the attempt to discover what it was that had fallen upon the wagon. The fellow's screams to the horse were futile. The animal had an idea that it was under fire. It bolted across the Piazza and swung eastward along the Via di Porcellana, leaving chunks of nice green grass to mark the track of the rocking wagon!

Halfway down the Via di Porcellana, Robert Henry Blane slipped from the end of the wagon and dived into a side street. He picked the wisps of grass from his smart suit and congratulated himself on the fact that he was wearing a blue serge.

"Curiously I had a desire to wear this in place of a gray suit," he murmured thoughtfully. "Gray would have shown the marks of that grass dreadfully."

The evening had closed in swiftly. Robert Henry Blane, hurrying up side streets, considered his position. Florence, for him, had claws of steel. In the city of Lorenzo the Magnificent was the girl he loved. There would be, of course, a Legion of little officers of the secret police searching for him, but he cared little for the Italian police.

He made half a dozen purchases at the shop of a coiffeur, carried these purchases to a small hotel and rented a room. For a full hour he worked upon his face, worked with a knowledge and industry that would have done credit to the greatest actor in the world. He walked out into the street wearing a small mustache and a tiny-pointed beard.

He visited an outfitter's and bought a complete stock of necessary articles, packed them in a new grip, called a cab and drove to the Hotel Grande Bretagne. For the moment he discarded the name of Robert Henry Blane. He registered as Sir Humphrey Linburn, was shown to a suite on the first floor, and there leisurely improved upon the alteration he had made in his appearance. He changed from the light-blue serge suit into a close-fitting walking costume, the rakish velours was replaced by a silk hat made in the latest Paris style; collar, tie, and gloves shifted from plain common sense to dandified astheticism. Shoes also. A monocle was added. For fifteen minutes Sir Humphrey Linburn paraded before the big mirror, then feeling that the last traces of Robert Henry Blane had been extinguished, he walked out onto the street. He was prepared for all the secret police of Florence. He ambled along like a boulevardier. Male passers-by looked enviously at his clothes. Women glanced shyly at him. They though his mustache adorable, his manner elegant.

Robert Henry Blane, alias The Texan Wasp, alias Sir

Humphrey Linburn, made a gallant effort to forget the

information that had dropped from the red lips of Betty

Allerton. He tried to find distractions that would blot out

the knowledge. He visited the Politeama Fiorentino to watch

a Russian ballet and left in five minutes. A Parisian dancer

at the Pergola held his attention for less. A variety show at

the Alfieri was appallingly dull. He tried dives and cafés

chantants with no better result. One huge and appalling fact

met him at every street corner and tried to throttle him.

Betty Allerton was going to be married. Betty Allerton of

Boston was going to be married! Betty Allerton who had pinned

a red rosette upon his breast when he had broken a college

record was going to be married!

He called the unknown count by many names. He called him a subway digger, a fruit peddler, and worse.

His own affairs were forgotten. It was the menace that faced Betty that occupied all his attention. Now and then he did recall that he had gone to a house that morning in the Via di San Gallo, a house occupied by a Greek named Kavados who was afraid of an iron box that carried a curious inscription. The inscription said the god of vengeance acts in silence. The Wasp repeated the words over and over. Well, the god of vengeance had worked in silence for Robert Henry Blane. The god was making him drink the dregs of bitterness. Fight as he might the gloom caused by the news clutched him. Betty had told him that she disliked the fellow, but what could a girl do against a designing aunt who had made up her mind about the man that her niece should marry? The aunt would win.

The Wasp recalled also the affair at the hotel. Not with any thrill. It was a small matter in his checkered career. He had given the slip to three little officers of the Italian secret police, but he had done that on many other occasions. The big incident of the day—the one thing that stood up above everything else was the news that Betty was to be married against her will to a penniless nobleman, a person of supposed blue blood who was buying wealth with a genealogical tree that wasn't worth a row of pins. A fellow who couldn't ride or fight, a niddering, a weakling, a chap whose one fighting forbear was the fellow who way back in the Middle Ages earned the title that was on the market for American gold. Well, the dollar was high; lire were shrinking every day!

"If it was an American I wouldn't grumble," soliloquized Robert Henry Blane. "I could stand that, I think. But a dollar-hunting European gets me—"

He broke off abruptly in his meditations. A man, leaning carelessly against the wall at the corner of the Via dei Lamberti straightened as The Wasp approached. The eyes of the fellow were upon Robert Henry Blane. Strange eyes—eyes that were cold and merciless; eyes that looked like brown—tinted and hard-frozen hailstones. There were other outstanding features. A short, big-nostriled nose that suggested the ability to analyze the air it breathed; a chin that had thrust peace to the winds. The man was No. 37, the most expert thrower of the lariat in the employ of Dame Justice!

The gray eyes of The Wasp did not flicker under the scrutiny of the man hunter. He kept straight on, twirling his nobby cane in the style of a leisured dandy. It had been a day of surprises, so one more or less would not matter.

The man hunter sauntered forward and addressed Robert Henry Blane, alias Sir Humphrey Linburn. Addressed him in English. "Pardon," said the sleuth, "are you the gentleman who told me to get you the price of the two pictures in the Morini Galleries?"

Sir Humphrey Linburn laughed loudly. "Out of bounds, old top," he said gayly. "Pictures? That's a good un! What the devil would I be doing with pictures?"

A doubt, which had been visible in the cold eyes of the detective, grew larger. His voice showed the effect created by the Piccadilly drawl of the dandy. He begged pardon.

"That's all right, old horse," said the imitation Sir Humphrey. "I don't doubt your mistake was genuine. But I don't know a picture from a prayer rug. Rotten bad taste, I know, but that's me."

He flicked an imaginary morsel of dust from the thumb of a glove and went on, a seemingly carefree and contented man. From the corner of one eye he glanced at the man hunter. The face of No. 37 expressed the most profound amazement and surprise.

The Wasp crossed the Piazza and returned. The sleuth had not moved. He was still standing with his back against the stone column, the cold and merciless eyes watching the stream that passed. Blane was upon him before he noticed. The dandified Sir Humphrey Linburn pushed the man hunter playfully in the ribs with his walking stick and addressed him.

"Fooled you that time, old dear," he drawled. "You said to yourself here's Bob Blane of Texas and you ran into a snag. Eh, what?"

The great sleuth stared at the dandy before him. "I'll own up," he said. "After you passed I looked at your back and said to myself that is Blane, then—well, you fooled me. That's all. And I was so darned pleased when I saw you coming. You see I was just aching to see you. Just aching to see you!"

"Why?" asked The Wasp.

"To get an address from you."

"Whose address?"

"The address of Kavados the Greek."

From the lips of Robert Henry Blane, alias the Texan

Wasp, alias Sir Humphrey Linburn came a soft whistle of

astonishment. For an instant he wondered if his capable

wits had turned traitor. Kavados the Greek! The day seemed

to be nothing but Kavados the Greek! Mentally he damned the

Greek. Why had the tricky scoundrel from Corinth demanded his

services in the matter of the iron box?

"I know nothing about Kavados!" cried Blane. "Yes, I took to the hospital a Greek named Calimara whom three little secret-service men have told me was Kavados, but as to—"

"Listen, Blane," interrupted the sleuth. "Listen to me! I know about the visit of the police to your hotel and your get-away. I heard it all. That's nothing. The house where you found Kavados is the place I want to find. Let me talk—here, come down here!"

The man hunter gripped the arm of Robert Henry Bane and half dragged him down a side passage to a cheap wine shop. The band upon the Piazza made confidential talk impossible.

"Let me have first say!" cried the sleuth. "Please! In some way that I don't know of you met Kavados the Greek. Leave that for the moment. What I want to tell you is this. On the night before last there was stolen from the home of a Florentine nobleman an iron chest. An extraordinary chest. It is known to many as the Iron Chest of Giovanni the Grand. Are you following?"

"As well as I want to," snapped The Wasp. "I'm tired. Had a sort of hard day. If you can cut the story in any way I'll be delighted. You see—"

"Don't be whimsical!" interrupted the man hunter. "As a favor to me, please listen. I was at Venice. I got a wire and came here. The chest was in charge of an honest man. A splendid man. His family is of the oldest stock in Florence. But they're poor. Dog poor! He has a son, a fool. The fool son wanted money and he listened to a bait. Not from Kavados. No, no! From a crowd bigger than Kavados. The box held papers that would cause trouble in three countries. Secret documents and the Lord knows what. It can't be told what is in it. The men who know weep when you question them. That's why I'm here."

"Interesting, I'm sure," drawled The Wasp.

No. 37 sat for a moment and regarded the big American. The hope that had flamed across his face seemed to be slowly dying as he studied the face of the dandy before him. Robert Henry Blane dismounted his monocle, polished it carefully, then put it back into place. He seemed fearfully bored.

"Continue, my good fellow." he said languidly.

"They got the chest," said the man hunter slowly. "Got it into the street. Something went wrong with their arrangements then. I don't know what. Fright, maybe. They got stampeded and were afraid to take the chest to the place appointed. Thought they were followed, perhaps. They looked for a place to hide it and one of their number suggested Kavados the Greek. He's a fence. They took it there. That's about all I can tell you. You know the rest. Kavados turns up in hospital with a bullet through his shoulder and near dead from loss of blood. You brought him there!"

No. 37 looked intently at Robert Henry Blane. Blane yawned. "Playing the good Samaritan in Florence is a foolish business," he said. "The next time I see a perforated Greek on the side of the street I am going to leave him there."

The cold eyes of the man hunter were warmed for an instant by the flame of temper produced by the attitude of the American. His strong hands were clinched. The lipless line of the mouth was hardly visible.

"You won't tell?" he demanded.

The Wasp paused in the act of lighting a cigarette and looked with calm gray eyes at the great rounder-up of criminals. "You have had your moral sense ruined by consorting with cheap people," he said coldly. "If I did know I wouldn't tell, and, as I don't know, the possibility of your getting the information is more remote still."

No. 37 half rose from his seat and thrust his jaw across the table. The audacity of the Texan maddened him.

"There are a few things that I have forgotten," he growled. "A few things that concern a dashing devil from Texas!"

"Dig them out and be damned!" snapped The Wasp.

The man hunter sank back into his seat and drummed with his knuckles upon the table. Robert Henry Blane blew smoke rings and stared at the blackened ceiling. From the Piazza came the strains of the Italian national anthem.

The swinging door of the wine shop was suddenly pushed open. A queer white face was thrust into the room. The small eyes in the midst of "made-over" features that represented a triumph of modern surgery brought into being by the war, noted the sleuth. The owner of the face advanced. Blane recognized him as the strange assistant of the man hunter.

"I was looking for you," said the newcomer in a high-pitched voice.

"What is it?" questioned the man hunter.

"The Greek has thrown a seven," replied the owner of the manufactured features.

"Turned up his toes an hour ago. Lost too much blood."

The great detective glanced at Blane. The Texan stared at the ceiling. The man with the made-over face hung around waiting for instructions.

After a long pause No. 37 began to speak in a low voice. His words were not addressed to any one in particular.

"It's the very devil to have pride and ancestry and have no money," he began. "The folk of this old man that's in trouble run right back to the time of the Guelphs and the Ghibellines. They rubbed shoulders with Charles of Valois and Cosimo. With Lorenzo the Magnificent and Giovanni the Grand. He showed me a genealogical tree to-day that looked like the plan of a skyscraper. They were in the ring seats, so to speak. When one of 'em bought a palace the other three hundred and ninety-nine that formed his set came and bought houses around him. And now the boodle has flitted and they're as poor as church mice. A nice white-haired old man with a fool son."

He paused, waited for a few minutes and went on. Robert Henry Blane had another fit of yawning. The man with the "triumph-of-modern-surgery-face" watched his master.

"It's not like that in America," went on the sleuth. "There a man can go out and gather up a new fortune if his father and grandfather have dissipated the one they had. America is a land of golden opportunities."

Robert Henry Blane tossed his cigarette into the box of sawdust on the floor and reached for his gloves.

"This place is different," said the detective, looking hard at the big American. "This place is altogether different."

"I didn't say they resembled each other," murmured The Wasp. "You have the appearance of a man who wants to start an argument."

"No, no," protested No. 37. "I was trying to get you to take a fair view of this matter. What chance have these people got here? They've squeezed old Mother Earth till she's dry. They've got no chance. They've lost everything but their damned pride, and the poorer they get the prouder they get. This boyish ass who is responsible for all this trouble had a dream of putting the family on its feet. That's why he fell for the scheme of the trickiest scoundrel in Europe who paid him a bribe to let his thieves into the house. He wanted ready money for his own little scheme. The aunt of an American heiress had flattered the fool and he thought that he might marry the heiress and rebuild—"

"What is the name of the heiress?" snapped The Wasp, turning fiercely upon the man hunter.

"I don't know," answered No. 37, a little amazed at the Texan's sudden change of manner. "Why?"

"Can you find out?" demanded Blane.

"Yes, in one minute. I can phone to the boy's father."

"Please do!"

The great detective entered a little phone booth at the rear of the shop. Robert Henry Blane, alias The Texan Wasp, alias Sir Humphrey Linburn, walked to the door and stood looking out into the soft night. He was thinking of Betty.

The door of the telephone booth banged. The Wasp turned as the great sleuth came toward him.

"The name of the young lady is Miss Allerton," said the detective. "She has shown him no favors, but he thinks her aunt is friendly."

Blane thrust the swinging door open and strode into the night. A taxi was coasting across the Piazza. He flung himself into it, followed by No. 37 and the person with the made-over face. The detective whispered an address in the Via Toscanella, and the car rolled westward toward the Ponte Vecchio, the bridge of jewelers on which the crippled beggar had spoken to Robert Henry Blane.

No. 37 glanced at The Wasp as the taxi pulled up before the

door of a mansion that had seen better days. A tired, decrepit

mansion. The two stone lions before the door were earless

and noseless. Their tails had been chipped away by legions

of youngsters who had played in the street. Upon the house

had fallen the scum of the centuries; the scum of death. A

few yards away were the Palazzo Pitti and the Boboli Gardens,

visited every year by thousands of Americans who come to

admire the treasures and ponder over the old-time glory of the

city.

No. 37 sprang to the pavement and looked at The Wasp: The eyes of the big American were upon the house. It showed in the moonlight like an old hag. It brought to him a feeling of disgust. It belonged to another era. It was connected with a dead past. Like its owners it had lost vigor and life. It was a battered old thing that should have been torn down to make way for homes built in accordance with the laws of hygiene. To Robert Henry Blane came a longing for Texas, a tremendous longing for places that were new and clean, places where the wind of God was fresh and wholesome, untainted by the hates and feuds of dark days that we have outlived. He longed for America—for home!

"Will you come in?" questioned the detective.

"No," snapped Blane. "Bring him here! The young fellow! We've got a job before us and—well, he might be useful if there's a fight."

The detective gave a cluck of delight and dragged at the doorbell. An old servant answered the ring, the sleuth pushed him aside and entered. The Wasp remained in the taxi.

Within three minutes the man hunter was back, accompanied by a tall and pallid young man who was carefully and meticulously dressed in evening clothes. To the cool gray eyes of Robert Henry Blane the young man resembled one of those effeminate gentlemen who wait like well-groomed spiders in the anterooms of fashionable Parisian dressmakers, ready to wind their skeins of humbug and flattery around the unwary women who enter the places.

The man hunter presented the fellow with a grin of amusement. "Count Angelo Ammanati," he said slyly.

The big Texan took the soft hand that the count extended. He wondered what in the name of creation was happening in the old dark house that forced the fellow into evening dress. "We interrupted you," said Blane. "You are entertaining, eh?"

"No, no," drawled the count. "I am alone. I dined alone."

The Wasp moved over on the seat. "Then step up here," he said sharply. "Step up and take a ride."

"Oh, no," said the aristocrat. "I don't know you and—"

He didn't finish the remark. Robert Henry Blane leaned quickly forward, grabbed the right wrist of the young man and literally dragged him into the cab. Count Angelo protested, but his protests fell on deaf ears. The big American, without exerting any great amount of force, crammed the last branch of the Ammanati genealogical tree onto the seat beside him. He thought the branch was a very weak thing indeed, a sort of feeble twig on a dead trunk.

The Wasp had taken charge. He turned his head to find that No. 37 had jumped upon the running board. The sleuth was amused. He leaned forward as if seeking an address.

"Via di San Gallo!" cried Blane. "Tell him to pull up opposite the School of Medicine."

Count Angelo Ammanati's protests were deafening. He demanded reasons and The Wasp, gripping him tightly by the wrist, gave them. "Listen, little Angelo," he said, "a friend tells me of the loss of an iron chest through a brain storm of yours. We are—"

"You—you mustn't speak to me like that!" shrieked the Italian. "How dare you? Stop the car and let me out at once!"

Robert Henry Blane laughed. "We are going after the chest," he said softly. "Going after the Iron Chest of Giovanni the Grand. There might be trouble and we wanted an extra man. I know where the chest is but there are others who know too. There might be gun play, so we—"

The count tore himself away from the grip of the American and tried to thrust himself through the window of the cab. Robert Henry Blane dragged him back and placed him gently on the floor of the machine. Mr. Blane wondered about Aunt Diana and Betty Allerton. He thought it was unlucky for Betty to be in such close relationship with a lady like the Comtesse de Chambón who, through marriage with a French nobleman, had conceived a great regard for titles. Blane wondered what Betty could do with Count Angelo, and, while he was wondering, the count bit him fiercely on-the ankle. The scion of the Ammanati's was nearly off his head with injured pride not altogether unmixed with fear.

The Wasp rescued his ankle from the teeth of the highborn one as the automobile pulled up before the School of Medicine in the Via di San Gallo. Mr. Blane was considerably annoyed with Count Angelo. He considered the fellow ungrateful, and, with no tender hands, he rushed the aristocrat across the street and up the steps to the house where he had interviewed Kavados the Greek some twelve hours before. A rather exciting twelve hours, thought The Wasp. Twelve hours crammed with excitement and trouble; threaded by a golden interlude when he had walked with Betty Allerton along the river in the soft afternoon.

The house of Kavados was in darkness. The door was locked, but No. 37 was an expert in the matter of locks. He dropped upon his knees, fumbled for some few minutes with a queer instrument that he carried, then thrusting his shoulder to the door he pushed with all his force. The door opened and the detective went sprawling forward on the carpet.

The Wasp, holding to Count Angelo, stepped into the reception room; the man with the made-over face followed. The sleuth got to his feet and closed the door.

No. 37 spoke. "What are the orders, Blane?" he whispered. "You know the way."

The Wasp did not answer for a moment. He was listening intently. From a distance came a dull scratching noise, a noise suggesting that an object of great weight was being dragged along a tiled floor. He reached out a hand and touched the arm of the detective.

"What is it?" murmured the sleuth.

"They are moving the box," answered Blane. "Listen! It is in the cellar at the end of a long corridor. Listen!"

The noise increased in volume. There came to the ears of the listeners the tramp of heavy feet upon the stairs leading down into the cellar. Grunts, whispered curses, and curt orders came out of the darkness. The nail-studded door that Blane remembered at the top of the cellar stairs was banged fiercely.

The volume of noise increased. A will-o'-the-wisp light appeared afar off. More grunts; curses without end, then a deafening crash as the chest was thrust up into the corridor.

No. 37 leased forward and whispered to Robert Henry Blane. "Better tackle them now," he said.

The cool Texan grinned softly. "It's an awful weight." he murmured. "Let them carry it along the passage. It weighs a ton."

Count Angelo Ammanati thought it time to go. He figured out the position of the street door, made a sudden break from the clutch of The Wasp and bolted.

Angelo didn't go far. His bump of location was not well developed. He tripped over a chair, screamed like a startled jack rabbit and fell full length upon the floor. Then Old Man Commotion broke loose in the house of Kavados the Greek.

The light of the lantern at the end of the passage was immediately doused, some one shouted an order; then there came the hurried tread of feet along the corridor. The carriers of the iron chest had left their job for the moment and were intent on finding out who had invaded the house.

Robert Henry Blane acted quickly. He sprang across the room to the point where the hall entered the chamber, and hurriedly tipped an enormous chair so that it lay in the path of the charging gang.

The effect of this strategy was remarkable. The hurrying bearers of the Iron Chest of Giovanni the Grand tripped over the obstacle and came sprawling into the reception room. One, two, three, four! They came over the capsized chair; curses and yells of rage adding to the noises made by falling glassware and battered furniture.

An automatic barked and a string of profanity became a scream of pain. Blane's fingers came in contact with a large brass pot and he brought this weapon down on the head of a person whose accent was foreign to him. Again the revolver spoke. A mirror crashed! The table in the center of the room was overturned. Some one had found the door and was fumbling at the lock.

"Blane?" whispered the detective.

"Here," answered The Wasp.

"Good," snapped the sleuth. There was a spurt of flame, another report, and the fumbler at the lock dropped. From somewhere in the corner came the frightened scream of Count Angelo Ammanati.

There was a moment of near quiet. Tumult fled for a space and left nothing but choking groans and curses. No. 37 pressed the button of a flash.

There was an immediate report. A bullet crashed through a piece of pottery. Some one swung a chair, there came a deep groan, then the voice of the sleuth's assistant came softly. "I think you can flash again," he said softly. "The four are knocked out."

No. 37 pressed the flash. Upon the floor, in the debris of battle, were four men. Two were unconscious, one—the fellow that The Wasp hit with the brass pot—was sitting up holding his head in his hands, and the fourth, although wounded badly, was still fumbling with the lock of the door in an effort to escape into the street.

No. 37 pounced upon him. Like lightning the bright handcuffs of the sleuth were upon his wrists. A gurgle of joy came from the thin-lipped mouth of the man who worked night and day for justice. He had made a killing!

"Blane!" he cried. "Come here! Do you know this chap?"

The Wasp stumbled across the room as the sleuth's assistant ell upon the only other conscious one cf the four. The detective held the flash light, and Robert Henry Blane looked down into a white, thin face in which were large dark eyes, set close together and lit up with a brilliancy that suggested fanaticism. The thoughts of The Wasp flashed to Como, then to the Promenade des Anglais at Nice! The person before him, whose long, lean hands were clutched together, was the Mystery Man from Prague!

There came a knocking at the door, the demands of the police aroused by the firing. No. 37 signaled for Blane to open it. "I'm hit somewhere," said the sleuth faintly. "I don't know exactly where. Keep your eye—keep your eye on—on this bird, will you? I—I—" He stopped talking and slipped softly to the floor beside the mysterious person whom old General Rumor blamed for half the unfortunate happenings of Europe.

Blane opened the door; the lanterns of the police illuminated the room.

An hour later Robert Henry Blane stepped from the door

of the old mansion in the Via Toscanella. A white-haired man

clung to his right arm and thanked him again and again. The

son of the old man, a trifle sulky and unrepentant, followed

the big Texan. Mr. Blane had read the riot act to Count

Angelo Ammanati, and the young fool had not quite recovered

his temper. But he was a much sobered Angelo. Thoughts of

American heiresses whose money would rebuild the glories of

the Ammanatis were, for the moment, dispelled. He had agreed

to leave immediately for a little farm in Tuscany owned by a

poor relative.

"And let me give you a farewell word," said The Wasp, addressing the youth as he stepped into the taxi. "Try and dig your fortune out of the ground with a plow. With a plow and a couple of Tuscan bulls. It's the best way. Good night."

Robert Henry Blane made a hurried call at the Hospital of Santa Maria. No. 37 was sleeping peacefully after a slight operation. There was no danger, so the night surgeon said.

Blane came back to the taxi. He stood a moment on the pavement, thinking. The chauffeur watched him. The Wasp pulled at the little mustache that was part of his disguise as Sir Humphrey Linburn, and, to the great surprise of the chauffeur, the little morsel of hair came clean away from the lip of the Texan.

The chauffeur grinned; Robert Henry Blane frowned. The handsome adventurer from Houston recalled his escape from the Grand Hotel. He thought of the newspapers, of the silly things that Betty Allerton's aunt would find in a story of his arrest.

"To the Stazione Principe!" he cried. "Hurry! I want to catch the one-ten for Genoa!"

In the cab The Wasp carefully affixed the little mustache, took from his pocket his monocle and adjusted it. He stuffed a silk handkerchief into his coat sleeve, then lay back on the seat. For a moment he had a desire to sleep, but he overcame the desire and warbled in a Piccadilly accent:

"You longed to roam from your bally home;

You bragged of your wanderlust;

You studied the map like a crazy yap.

Now you'll travel, by gosh, or bust!"

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.