RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

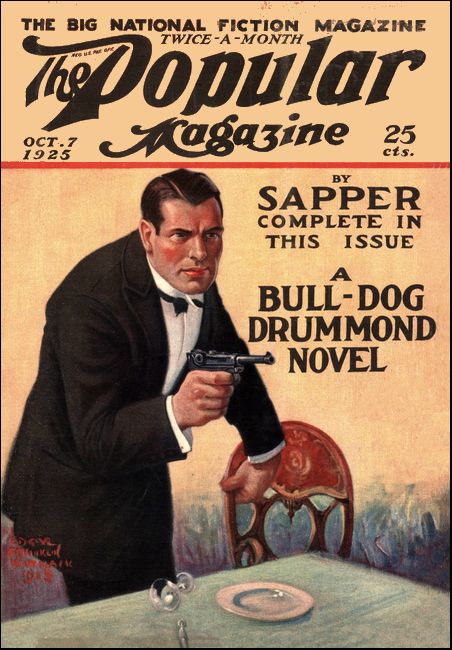

The Popular Magazine, 7 October 1925, with

"The Blue Houseboat of Muskingum Island"

James Francis Dwyer

JAMES FRANCIS DWYER (1874-1952) was an Australian writer. Born in Camden Park, New South Wales, Dwyer worked as a postal assistant until he was convicted in a scheme to make fraudulent postal orders and sentenced to seven years imprisonment in 1899. In prison, Dwyer began writing, and with the help of another inmate and a prison guard, had his work published in The Bulletin. After completing his sentence, he relocated to London and then New York, where he established a successful career as a writer of short stories and novels. Dwyer later moved to France, where he wrote his autobiography, Leg-Irons on Wings, in 1949. Dwyer wrote over 1,000 short stories during his career, and was the first Australian-born person to become a millionaire from writing. —Wikipedia

It was a baffling task, that of finding one small houseboat on the tremendous reaches of the mighty Ohio River. But The Texan Wasp was shrewd and determined and spurred on by the hidden clues so cleverly dropped by a charming girl.

THE soft charm of a dying summer had fallen upon Manhattan. A bluish veil, the gift of a sun god, shrouded the Hudson and the Jersey shore. Skyscrapers took to themselves infinite charm through their backgrounds of coral pink and flaming amber.

Robert Henry Blane, looking out from the wide windows of his bachelor apartment at The Montespan, surveyed with a certain ecstatic joy the city spread beneath him.

A gentle tap at the door roused The Texan Wasp from his daydream. His ordered "Come in" brought the negro servant, Peter, whose face, from too close proximity to the stove at which he was preparing his master's dinner, hinted at an oil well in his interior.

"What is it, Peter?" asked Blane.

"A tallygrem, suh," answered Peter. "I'se tole the boy to jest wait an' see if there's anny answer."

The Wasp took the message, opened it and read it slowly.

The message ran:

IF POSSIBLE CATCH ST. LOUISAN EXPRESS FOR PITTSBURGH LEAVING PERM STATION AT SIX TWO. LADY AND GENTLEMAN ON TRAIN WILL SPEAK TO YOU. THEY ARE IN GREAT TROUBLE AND I HAVE RECOMMENDED YOU AS ONE PERSON I KNOW WHO COULD HELP THEM OUT. PLEASE MAKE GREAT EFFORT. REGARDS. THIRTY-SEVEN.

Robert Henry Blane softly hummed a verse while Peter hurriedly prepared the valise.

Peter, valise in hand, reported. "All ready, suh. I'se tallyphoned for a keb."

IT so happened that Robert Henry Blane was the last person

to board the train. As the smiling porter escorted him to his

seat, Blane wondered at what point on the run would the two

persons mentioned in the telegram of the great man hunter

make themselves known to him. The sleuth had supplied no

descriptions. He had simply said "lady and gentleman," and

beyond this Blane knew nothing except that the pair were in

great trouble.

Blane, not instructed to do the seeking, remained in his section. Voyagers strolled through the cars, showing that queer restlessness of travelers, and The Wasp examined them in a languid way as they passed. He had a belief that he would immediately recognize the persons who sought him, recognize them because their questing spirit would come out and touch his receptive soul.

And one of the two came. As the express scurried by Rahway, a tall, slender woman with a patrician face, curiously and exquisitely shadowed by grief, slipped into the car like a timid spirit in doubt as to its whereabouts. Her large, brown eyes fell upon Robert Henry Blane and clung to his face for a long moment as if they found in the well-cut features of the Texan an anodyne for the pain that had brought the veil of sadness to them.

She passed, leaving The Wasp certain that she was one of the two who sought him. He thought of the man hunter's wire regarding trouble. Some great grief had brought to the wonderful face that strange spiritual quality that we see sometimes in the portraits of persecuted saints and martyrs.

Dinner was announced, and Blane went forward to the dining car. He looked for the woman as he passed along. He was quite certain now. He felt that her desire for his help came to him as the train roared along. He thought it curious.

The conductor of the dining car led the tall Texan to a seat into which he dropped easily. The chair immediately opposite was unoccupied, but its companion on the same side held an elderly man whose sun-tanned face was ornamented by a gray mustache.

Instinctively Blane glanced at the occupant of the chair beside him. It was the lady of the big, brown eyes.

The meal progressed with that strange jumpiness common to railway dining cars all over the world. The man and the woman exchanged remarks in quiet tones. They were ordinary remarks. The people commented on the service, on the towns through which the train fled like a pursued demon. Blane's keen ears told him they were not American.

They finished their meal. The man ordered a cigar, then, leaning forward, he addressed the Texan.

"Pardon me," he murmured, his cultivated voice lowered so that it was barely audible, "may I ask if you are Mr. Robert Henry Blane?"

"That is my name, sir," replied The Wasp quietly.

The questioner gave a little sigh of relief as he took a card from a small sealskin case and handed it to Blane.

"We were afraid that you could not come," he said, his voice still low and rather tremulous. "We are delighted at finding you. I am Lord Ruthvannen, and this lady is my daughter, Lady Dorothy Carisbrooke."

The Wasp bowed to the owner of the big, brown eyes, and she, in turn, expressed the joy that she and her father experienced in finding him upon the train. Into the soft liquid tones there came a note of thankfulness that made the adventurer from Houston blush as he listened.

"But I was only too glad to come," he said gallantly. "I was bored at having nothing to do."

A sweet smile appeared for an instant on the beautiful face of the woman. It was there for an instant only. Grief pounced upon it and it vanished. Robert Henry Blane wondered what tremendous sorrow had fallen upon the two persons to whom he had been recommended by the great man hunter.

Between Philadelphia and Harris-burg, The Texan Wasp heard the narrative. A queer narrative. The low, tremulous tones of Lord Ruthvannen that were drowned out at moments by the roar of the flying express seemed to make it more unbelievable.

The husband of Lady Carisbrooke had been killed leading a charge of Gordon Highlanders in the last days of the war. Of the marriage there was one child, a girl, sixteen years of age at the time of her father's death. And it was around this girl that the story centered.

In the years that had elapsed since the death of the father extraordinary attempts had been made to kidnap the daughter. Amazing and deep-laid plans by persons whose motive was a mystery. The terrified mother and the alarmed grandfather had moved from place to place in an effort to dishearten the gang who were endeavoring to abduct the girl, but the unseen pursuers followed.

Ruthvannen and his daughter fled England and crossed to the Continent. The stealthy kidnappers were close on their trail. An attempt to seize the girl in the Avenue de Trianon at Versailles was foiled by a miracle. Cold fear at their hearts, the mother and grandfather fled to Florence and registered under assumed names. On the second day the girl was attacked on the Lungarno by masked men who were beaten off with the aid of three American tourists who came in response to the mother's cries.

The mysterious attempts continued. The shadow followed to Venice and Milan. In despair the mother and grandfather rushed to Genoa and took ship for the United States. Ruthvannen's wife had been a beautiful Kentuckian who took the English nobleman's heart by storm during her first season in London, and Lady Dorothy Carisbrooke, with all the admiration of America instilled in her by her dead mother, thought that in the country of freedom she would find protection against the devils who followed relentlessly.

"We occupied an apartment in Central Park West," came the whispering voice of the elderly lord. "We thought no one knew of our arrival. We were beginning to breathe freely for the first time in months, then—then—" He paused and looked with moist eyes at Blane.

It was Lady Dorothy Carisbrooke who took up the narrative.

"Five days ago my daughter, Evelyn, was kidnapped," she said gently. "We were in Central Park when an automobile swooped down upon us. I was knocked down by the machine, and before I could get to my feet Evelyn was dragged inside the car. It disappeared around a turn in the driveway and we haven't seen her since."

Robert Henry Blane was looking at Lady Dorothy. The large brown eyes were swimming in tears. The swift recital of the happening was agony to her.

"And now you have been acquainted with the motive?" asked the Texan.

Ruthvannen nodded.

"Yes," he murmured. "We have been told the motive."

He paused for an instant, then went on. "I think I had better show you the letters we have received, then you will know everything."

From his pocketbook he took a small bundle of letters, one of which, written on paper of a bluish tint, he handed to Blane.

The Texan Wasp opened it and read it slowly. The handwriting was that of an uneducated person, and the epistle bristled with mistakes in grammar and spelling. It ran:

The rite honnereble the earl of ruthvannen. You ole hound, you arrystocratick blighter you doant remember me i bet. Ime Bill Staggers an you handed me a little bit of orlrite at derby assizes, youole mucker you give me a stretch o ten years fur jest choking a fat chump to get his poke, my wife jane Staggers an her littel girl died when i was in the pen an arfter i came out i went away to australia an made a fortune on the goldfields at coolgardie then i sed to me-self ile go back an give that ole blighter a shake up and ime doin it not arf am i. Ive got yer grandorter an i doant no yet what ime goin to do with her. maybe Ile marry her to a nice young chap who belongs to my gang, cheerio, ile let you no later.

Robert Henry Blane lifted his head and looked at the old nobleman. "Do you remember this fellow?" he asked.

"Perfectly," answered Ruthvannen. "I sat at Derby assizes some sixteen years ago and I recall a case in which I sentenced a red-headed man to ten years' imprisonment for garroting. I have forgotten the name, but I suppose it is Staggers. I'm sure it is. Here is the second letter."

The Wasp took the second communication from Mr. William Staggers, one time of Derby, England, and later of Coolgardie, western Australia. It read:

Call off the bulls or miss evlin wil be tootin with the angils. she woant marry that young chap i tole you of so i doant no wot to do with her jest yet. i mite kill her if you doant mussil the cops, she wants to let you no she issent ded so ime lettin her rite you a line you ole swine you dident worrey that much over jane staggers an my littel girl, but call off the bulls or this mite be the larst letter she is goin to write.

"Did you call off the police?" asked Blane.

Lord Ruthvannen nodded. "I told them that my granddaughter had eloped," he murmured. "I was afraid, horribly afraid. I managed to keep it out of the papers when the kidnaping took place."

"And the inclosure?" asked The Wasp.

The nobleman handed over a scrap of white paper, evidently torn from a notebook. Both sides were covered with writing, the penmanship bold and of that peculiar angular style adopted by well-educated Englishwomen. Blane read with interest the following:

Dearest Mother:

Do not use the police. It is dangerous to me. I am well treated. Oh, honey, I often rise in violent exasperation resenting greatly grandfather's cruelty to Mr. Staggers!

Best love unto everyone.

Evelyn Primrose Carisbrooke.

Lord Ruthvannen spoke while The Wasp was still reading the message.

"The person who was good enough to wire you to help us solved the message contained in Evelyn's note," he said. "You will possibly see the secret if I tell you that Evelyn never calls her mother 'honey' and that she has no claim to the name Primrose."

The gray eyes of the Texan were fixed on the sheet and each word was subjected to a fierce scrutiny. At the beginning of the fourth sentence he discovered the clue. The first letters of the words that followed made "Ohio River." The same principle applied to the fifth sentence gave the word "blue."

Blane lifted his head and looked at Lady Dorothy Carisbrooke.

"And what does 'Primrose' convey?" he asked.

"It was the name of Evelyn's houseboat at Staines," answered the mother.

A little smile slipped over the handsome features of the adventurous Texan. He conceived a sudden liking for the kidnapped girl who, under conditions that must have seemed terrible to her, had possessed the sang-froid to write a message that gave her terrified relatives a clue to her whereabouts.

Blane looked at his watch. It was ten twenty-five. The express was plowing by Marysville.

"I will wish you good night," he said, bowing before the old nobleman and his daughter. "It is always nice to think of to-morrow when to-day has been full of pain."

Lady Dorothy Carisbrooke rose quickly and gave her hand to the Texan.

"I—I have confidence in you," she murmured. "Hope came into my heart when I saw you in the carriage before dinner. Oh, I knew it was you! You look—you look as if you could do things! You will help, will you not?"

Robert Henry Blane stooped and lightly kissed the fingers that he held.

"I will do everything I can," he said quietly. "I am at your service till we find your daughter."

A BLUE houseboat on the Ohio! A needle in a haystack! A

grain of wheat on the dusty road to Mecca!

The Texan Wasp stood on the Sixth Street Bridge and watched the waters of the Allegheny hurrying to join those of the Monongahela at Wabash Point. There they lost their identity and became the splendid, broad and muscular Ohio that goes rolling and tumbling for nearly a thousand miles till it tips its offering into the Mississippi at Cairo Town. A great stream!

A man standing beside The Wasp, whose eyes were turned lovingly upon the rolling stream, spoke in the friendly manner of one riverman to another.

"It's great, isn't it?" he gurgled. "Say, she's a stream! Cussed at times, but the best river in America. I know her! Run the Powhatan up and down her for years."

"And where is the Powhatan now?" asked Blane.

"Broke her back on a lock wall!" snapped the other. "I'm Captain Haggerty an' there isn't an island or a government light, crib dike, run, landing, or sand-bar 'tween here and old Cairo that I don't know. I could feel my way down this river with my eyes shut. Some of these pilots have got to take a rabbit's foot in every one of their pockets or they'd pile their old stern-wheeelers up, but not me! Give me a twenty-foot plank an' a pole an' I'd make the Mississippi quicker'n a steam packet."

The Wasp offered a cigar. "I love modesty," he said softly, then, as the captain looked at him suspiciously, he added: "You might be helpful to me. I was thinking of drifting down the river in a houseboat. Just an ordinary houseboat with a small kicker to get her through the locks."

Captain Haggerty spat viciously.

"Don't!" he snarled. "That isn't a game for any one! I know 'em! There's chaps as live on leakin' pill boxes on the Ohio that'd kill a man to get his teeth stuffin'. I know 'em an' they know me. When I ran the Powhatan I useter stand in close to 'em an' heave their pill boxes onto the corn patches with the old girl's wash. One o' 'em shot at me once, the blamed river rat! Came out of his box an' unloosed a charge of buckshot at me. Only he was tossin' like a cork he'd 'a' got me."

"A friend of mine from New York took to the river," said Blane. "A tough baby. He had a houseboat, a blue one."

"Oh, some of 'em may be all right," admitted Haggerty grudgingly. "There are fellows who keep out of the way of packets. A chap is a fool to think he owns the whole stream, isn't he?"

"Maybe," said The Wasp. "This friend of mine that had the blue houseboat was contrary. You may have had a run in with him."

Captain Haggerty considered for a moment, his red eyes filmed as he turned them inward and looked down the river of memory etched within his brain.

"The last time I was down I saw a blue houseboat at the mouth of the Little Beaver."

"He might be my friend," commented Blane. "He was never what you would call a quiet citizen."

There was an interval of silence, then the captain, after a furtive examination of the well-fitting suit worn by Robert Henry Blane, spoke.

"Don't go down the river in a houseboat," he said. "'Cause why? 'Cause all the skippers of packets an' towboats hate 'em. That's why. Some night you'll find your pill box tossed into a West Virginny tater ground, an' if they don't do that to you they'll make kindlin' of you against a lock wall. Now I know where there's a forty-foot motor boat with a new engine an' sleeping accommodation for six. She's at Price's yards at the foot of Federal. You can get her cheap."

The Wasp surprised Haggerty by his reply.

"Let's look at her," he said quietly. "A motor boat would be better, I believe."

In the hour that immediately followed, Captain Haggerty of the Powhatan formed the opinion that the dashing person he met on the Sixth Street Bridge was a whale for action. Blane bought the motor boat Alequippa after a swift but thorough survey; he engaged Haggerty as a pilot and agent with orders to get the boat ready with all possible speed; then he dashed back to the William Penn to report progress to Lord Ruthvannen and his daughter. In the brief interview that had taken place between the nobleman and Blane after their arrival in Pittsburgh, Ruthvannen had handed over the conduct of the pursuit to the Texan.

"My daughter has implicit faith in you," he whispered. "She thinks that you will find Evelyn."

"I'll try," said Blane. "I'll try hard."

The Wasp sprang from a taxi at the door of the hotel as a well-built young man came sauntering up the avenue. For an instant the young man stared at the adventurer from Houston, then he unloosed a wild yell of delight and sprang toward him.

"Glory be!" he cried, as he clutched the hand of The Wasp. "Who'd have thought of meeting you? Don't you know me? James Dewey Casey, the 'Just-So Kid!'"

Robert Henry Blane gripped the shoulder of the little fighter whom he had met in the long ago at Monte Carlo, Seville, and other places, and rocked him gently backward and forward. The meeting gave him exquisite pleasure.

"Why, Jimmy, this is great!" cried Blane. "I thought that you were doing the European vaudeville circuit with your fighting billy goat."

"Some blighter stole Rafferty in Berlin," growled Mr. Casey. "Stole him an' eat him! They're cannibals, they are! If I'd have caught the fellows that chewed up old Rafferty I'd have cut their livers out. When I lost him I got disheartened an' I came home to see my mother in Brooklyn. She has a boarding house in De Kalb Avenue."

"And what are you doing here?" asked The Wasp.

"I hoped to get a scrap next week, but it's off," said the Kid.

"Do you know anything about engines, Jimmy?"

"Do I?" cried the pugilist. "Why, I drove machines during the war that were held together with pieces of string and court-plaster. I had an engine that was made up of parts of twenty-six other engines, an' it was—"

"You're hired, James," interrupted The Wasp. "First engineer on the motor boat Alequippa. She's at the foot of Federal Street. Report on board while I get our passengers."

"I like boats," said the pugilist. "That's why my mother put Dewey between James and Casey. She thought I'd—"

"Beat it, Jimmy!" cried The Wasp. "This is a hurry job."

The Alequippa cast off from her float above the Sixth Street Bridge at exactly twelve o'clock, and two minutes later the first evidence that Mother Trouble rode with the five voyagers was made evident.

The motor boat passed under the bridge on the north side of the channel and Blane at the wheel received a greeting as she slipped through. A man, leaning out over the bridge rail, fired at the Texan, the bullet striking the cabin roof some twelve inches in front of him, and at the same moment a stone wrapped in paper narrowly missed the head of Lord Ruthvannen, who was standing on the little deck.

The Wasp swung the boat around, his eyes upon the bridge. The half stagnant crowd had taken on tremendous activity. The sharpshooter had dashed toward the north side and the bridge loafers were streaming after him as if a monster vacuum was sucking them into Federal Street.

The Alequippa held her position against the current, all hands upon the deck. The commotion on the bridge died away. Men came running back to report.

A fellow climbed on the bridge rail, cupped his hands and shouted the news.

"He got away!" he yelled. "Got around the depot and escaped. Do you know him?"

"Never saw him," answered The Wasp.

"Fellow with a big felt hat!" screamed the man on the bridge. "Well, he got clean away. Here's a cop coming."

The policeman climbed up beside the man and demanded information. Who were they? Why did the man fire at the boat? Why didn't they return to the float and tell what they knew?

Robert Henry Blane glanced at Lord Ruthvannen. The nobleman made a gesture that signified his dislike to all publicity. The Wasp took the cue.

"We're scientists," shouted the Texan, as the cop leaned out and helped his ears by enormous palms. "We are taking a trip down the river to inquire into the family life and habits of mussels and other animals. Why the fellow shot at us is a mystery. And we are too busy to come back and chat with you. We're off. Good-by."

The Alequippa turned in her own length and headed downstream at a fifteen-knot gait, leaving an astonished policeman and an unsatisfied crowd upon the bridge. It was then that Lord Ruthvannen made a discovery. He picked up the stone that had grazed his head and examined the sheet of paper in which it was wrapped.

"There's writing on it!" he gasped. "Look!"

Blane turned the wheel over to Haggerty and took the wrinkled sheet of paper from the hand of the nobleman. The message was written in pencil and the creases made it somewhat difficult to read. Slowly The Wasp deciphered the following:

You'll get a bullet in your head, Bob Blane. You ain't better than anybody else. You were called some pretty warm names when the bulls were chasing you over there in Paris. Look out! The fight is on! Cut it out before we fit you for a wooden box.

Robert Henry Blane's jaws tightened. The old scar that temper made noticeable showed white against the tan. He pushed Haggerty away from the wheel, swung the Alequippa to the right of Brunot Island and headed for the first dam on the river. Mr. Blane was annoyed. Mr. Bill Staggers and his gang had declared war and war it would be.

Vanport appeared, and The Wasp edged cautiously toward the right bank as he approached Raccoon Shoals. A blue houseboat lay above the shoals.

A tall man with a bushy black beard fended off the Alequippa as she slipped alongside the houseboat.

"I wonder if you have a pint or so of drinking water to spare?" asked Blane. "Our barrel has leaked."

"You can get water at the dam," drawled the black-bearded one. "I've got to haul mine from the spring half a mile away."

"Is that so!" laughed the Texan. "Well, well!"

There was a moment of awkward silence, then from the inside of the houseboat stepped a plump, fresh-faced woman carrying a tin vessel full of water which she handed to Lady Dorothy with a smiling bow.

"Bill is like that," she explained, as the Englishwoman took the offering with both hands. "He's so gruff, but he doesn't mean anything."

Friction was wiped away by the gesture. Even the gruff and unfriendly Bill smiled as his wife asked Lady Dorothy if she wished to inspect the floating home.

The invitation was accepted. Ruthvannen and his daughter climbed aboard the houseboat and were shown with much pride the inside arrangements. There were two bunks, tables and chairs, a cooking stove and plate racks and everything was scrupulously clean and in perfect order. Lady Dorothy felt a little confused and ashamed as she returned to the Alequippa. The houseboat was the home of two peaceable citizens and she conveyed this impression to Blane as she came aboard.

The Texan made an offhand remark about the color of the houseboat as the Alequippa cast off. The houseboat owner grinned.

"I like blue," he shouted. "Lots of people like it. There are scores of boats painted blue."

Scores of boats painted blue! The Alequippa went on. There was no houseboat at the mouth of the Little Beaver River. A farmer on the bank supplied this information.

"One's headin' for New Orleans, mister," shouted the farmer. "Lots of 'em are driftin' down now to dodge the cold weather."

He guessed there were other blue houseboats. Not exactly round there, but downstream. He didn't know where. He hated the folk who lived in them.

Lock masters, lockmen, dredge hands, fishermen, farmers on the banks were questioned. The throats of Blane, the Just-So Kid and Haggerty were hoarse through continuous questioning. A blue houseboat? Couldn't say whether it was small or large. Couldn't say anything about the occupants. There might be a young lady aboard, also a red-headed man. The brown eyes of Lady Dorothy were moist as she listened to the inquiries and the empty answers.

They found false clues by the score. A lockman at Dam 8, just above Wellsville, Ohio, was certain that there was a blue houseboat tied up above Deep Gut Run—absolutely certain.

A water-logged scow on which a shack of flattened kerosene cans had been erected greeted the occupants of the Alequippa as they nosed into the West Virginia shore. A crazy river hermit in tattered rags and bent with age informed Blane that there was no other boat tied up there, and, by Jiminy, he wouldn't let any other boat tie up.

"There's only fishin' for one!" he screamed. "I don't want any one else here. Push on! I don't mean to starve to death!"

They came to Steubenville as the night fell and they tied up above the dam, a locking being refused.

A LITTLE after midnight the Just-So Kid aroused Blane.

"Say, boss, we're adrift!" he cried. "Some one has cut us

loose from the float!"

Jimmy was right. The startled Texan found that the Alequippa was out in the middle of the river, the current carrying her swiftly downstream.

"Quick!" he roared. "Start the engine! We'll be over the dam!"

The roar of the falling waters came plainly to the ears of the roused occupants of the motor boat. The dam was up, and the Alequippa was drifting swiftly toward the "bear trap" through which thundered the water of the throttled river. The three warning lights at the head of the lock wall and the two red lights at the foot shone in the thick darkness like the eyes of exulting demons.

The Just-So Kid started the engine. It faltered and died away as the speed of the drift increased. A startled scream came from Lady Dorothy as the moon, slipping for an instant from the enveloping clouds, showed the lip of the dam. The Wasp breathed a prayer and whispered encouragement to Jimmy.

The engine coughed spasmodically, then settled into a sweet roar of contentment, challenging the noise of the dam. The Wasp put the wheel over and inch by inch fought the clutching current.

He drove the Alequippa upstream, clinging to the West Virginia shore and steering by the chain of government lights that are strung along the dangerous passage from the head of Brown Island to Dam 10. He drove the motor boat into the shore below Light 560 and anchored under the high bank.

Haggerty reported that the ropes tying the Alequippa to the float had been neatly severed and a consultation was held in the cabin.

"It is certain that some one is following us," said Blane. "No one knew that we would tie up at Steubenville to-night, so the chances are that one of Staggers' gang has followed us from Pittsburgh. The betting is that he is somewhere near here now. We'll have to keep watch."

The Wasp took the first trick, ordering the others back to their berths, and as he stood on the deck, his eyes upon the river and the distant lights of Steubenville, Lady Dorothy Carisbrooke slipped out of her cabin and came to his side.

"I wanted to tell you something," she whispered. "To-night before this happened I had a dream in which I saw you crossing a great stretch of mud, and—and you were carrying Evelyn to me. I had a great desire to tell you. I know it will come true! I know!"

"I hope so," said Blane. "If we could pick up some clue, I would be relieved."

"We will!" gasped the mother. "I know we will!"

She slipped back to the cabin, leaving Robert Henry Blane alone with his thoughts. He was a little afraid of what might happen to Evelyn Carisbrooke now that Staggers knew there was an attempt being made to find the place where she was imprisoned.

Rain came with the dawn, a thin, misty rain that obscured the Ohio shore. A tow with four great coal barges came hooting downstream, whistling for a locking. It was a lumber-some big thing that looked rather frightening in the murky light.

Blane drove the Alequippa cautiously along at the heels of the tow. Terrifying things to delicately built motor boats are the lurching coal-laden barges of the Ohio. Those barges possess a devilish desire to horn small boats against the lock walls and grind them into splinters.

The Alequippa was locked through with the tow and Blane questioned the lockmen while being dropped to the lower level. Had a motor boat gone through since the moment he asked for a locking on the previous evening? The lockmen shook their heads.

The Alequippa followed the tow out of the lock, but, disregarding the channel, edged over toward Steubenville. The river mist had thickened. It was difficult to see the town.

Below the highway bridge that spans the river Blane crept in beside a junk boat that had used a half-sunken scow as a snubbing post. The junkman, a hunchbacked fellow with no claims on beauty, took the line that Haggerty flung to him and the Alequippa rested.

"Dirty weather," said The Wasp.

The hunchback nodded. River life had made him uncommunicative.

"Going down?" asked Blane.

The junkman shook his head. It was easier than speech, and if he wasn't going down it would be plain to the inquisitive one that he was coming up.

A woman with a strange peaked face came out of the cabin of the junk boat and stared in a fascinated way at the trim motor boat. Her eyes were red, suggesting recent tears; a small child had a strangle hold on her neck.

Lady Dorothy Carisbrooke found an apple and created a diversion 'by attempting to make the youngster accept it. The mother smiled; the junkman remained moody and solemn.

When the child was at last induced to accept the gift, Robert Henry Blane fired another question at the silent hunchback.

"Wonder if you noticed a blue houseboat anywhere along the river as you came up?" he asked. "A friend of ours is down here somewhere, but we don't know the exact spot."

The junkman regarded the river. He shifted his gaze to the Alequippa, examining in turn Lord Ruthvannen, Haggerty, the Just-So Kid, and Lady Dorothy, then his gaze came back to Blane.

"In my business I only see junk," he said solemnly. "'S matter o' fact I never see the folk as sell it to me. A chap comes with a hunk o' brass or lead or iron an' I just see what he's got an' nothin' more. Cops have asked me if I remember the fellers who 'as sold me certain things an' I've never obliged the cops once. That's why I'm a success. I hate cops."

Blane laughed.

"I'm not a cop," he said.

The junkman gave no intimation that he had heard. He had gone into the silence and refused to be baited into a controversy. He walked slowly to the small barge that acted as his repository for the things he collected.

The red-eyed woman regarded the five on the Alequippa. Her thin face showed a fleeting smile as Lady Dorothy tried to gain the attention of the youngster who was munching the apple. The Englishwoman asked the age of the child; the mother told with pride. She said he was big for his age. Lady Dorothy agreed.

A boy carrying a few scraps of iron climbed along the plank that bridged the scow and hailed the junk boat. The hunchback became immediately alert. He walked toward the prospective vender as Blane signaled Haggerty to cast off.

For the space of a few minutes the junkman was hidden by a makeshift structure that housed the cheap glass dishes and toys that he gave in exchange for the stuff brought to him, and the peak-faced woman seized the opportunity made by the temporary disappearance of her lord and master. She made a quick dash to the side of the Alequippa, her head thrust forward as she hissed a question addressed to Lady Dorothy.

"Did you—did you want to find a blue houseboat?" she gasped.

"Yes, yes!" cried the Englishwoman. "Oh, yes! Please!"

"There was one at Rush Run as we came up day before yesterday," cried the woman. "Big blue houseboat with a gas boat pullin' it."

Lady Dorothy Carisbrooke could not speak, but Blane flung a question at the woman.

"Did you notice the occupants?" he asked. "Did you see a red-headed man or a girl?"

The hunchback screamed for his wife and she fled in terror without replying. The Alequippa drifted away from the junk boat; the mist obscured the floating home of the collector of antiques. Blane had seized the chart and was running his finger down the river, softly muttering the names of the towns, islands, and runs marked thereon.

"Follansbee, Mingo Junction, Lazearville, Midway, Wellsburg," he murmured. "Brilliant, Beach Bottom Run...." He paused, his finger upon the chart, his eyes turned to Lady Dorothy Carisbrooke, who stood beside him.

"Rush Run!" she whispered. "Oh, oh!"

The Wasp shouted to the Just-So Kid and the Alequippa streaked downstream. Rush Run was barely ten miles away. She scooted by Wellsburg and whistled for a locking at Dam 11.

The lock master pointed to the rules that gave only hourly lockings to pleasure boats. The gray eyes of the Texan Wasp fell upon him like a flame.

"Pleasure boat!" cried Blane. "Pleasure boat? I want an immediate locking in the name of the law!"

THE gray river rolling by Rush Run was bare of boats of any

kind. Five pairs of eyes searched in vain for a vestige of the

blue houseboat.

The Wasp questioned an old man fishing from a stringpiece.

"There was a blue houseboat here, mister," croaked the ancient. "She lay for a day or two on the other bank. She slipped away in the night. Right by that tree clump she tied."

Blane swung the Alequippa around and headed across the river. He had a fixed belief that if the houseboat was the one that held Evelyn Carisbrooke an unwilling passenger, the girl, so clever at sending the first message as to her whereabouts, would make a further attempt to help the rescuers that she knew would take up the trail. The girl would find a way.

They found the spot where the houseboat had tied up. On the bank were blackened rocks that had served as a fireplace; scattered about were tins of all kinds—sardines, beans, corned beef, peaches.

Blane ordered the four to examine everything with infinite care. If the girl was on the houseboat, there would surely be some evidence around the camp. If she was clever enough to give a clue to her whereabouts in the letter sent to her mother, there would surely be some indication of her presence at this spot.

Blane's guess was correct. The Just-So Kid found a scrap of paper skewered with a thorn to a blackberry bush, and the wet scrap carried a message from the kidnapped girl. A message pricked with a pin on a dirty leaf torn from a book entitled: "Knight's Small-boat Sailing on Sea and River."

With infinite care the message had been pricked on the leaf. Blane, holding it high, read it to the listening four. It ran:

Am kidnapped. Blue houseboat bound south. Three men, one woman. Tell Lord Ruthvannen, care of British Consul, State Street, New York. Reward. Am in great danger. Evelyn Carisbrooke.

Lady Dorothy clutched the piece of paper on which the pathetic words had been laboriously pricked by the girl and pressed it to her lips. Her great brown eyes were wide with alarm as she stared at the deserted camp. She seemed stunned.

They helped her on board the boat and once more the Ale quip pa took up the pursuit. The misty rain became a downpour. It blotted out the banks. The river became a caldron of gray steam that made navigation dangerous. Day marks were indistinguishable.

The message from the girl increased the horror brought by the thought that they might pass the houseboat. The river was unfriendly. Haggerty whispered of backwaters as they slipped by Yorkville, backwaters like that at the rear of Pike Island, where a mile stretch of water would give shelter from the keenest eyes using the straight channel.

"We've got to take a chance!" snapped Blane. "We can't explore every hole and corner on the river. Hail everything that passes and question them."

A boat of the Eagle fleet was hailed off Burlington as she came slowly upstream. A tall-swearing captain, annoyed by low visibility and dictatorial lockmen, answered Haggerty's questions. He hadn't seen a blue houseboat. He didn't wish to see a blue houseboat and, furthermore, if he did see one he would run his packet over the blamed thing and tell no one what he had done. A congenial and friendly fellow was the captain.

Dam 12 was down, the river running wide, so there was no checking of boats that passed through. The Alequippa crept by Wheeling, standing close in to the left bank, Blane, Haggerty, and the Just-So Kid shouting questions at every one within hearing distance.

The blue houseboat was ahead. A float owner at Wheeling Creek confirmed the news. Red-headed man and two others. A fat woman, but no girl. A gas boat pulling it. Passed through two days before.

From Clarington to Baresville Station no person that they hailed had seen the houseboat, but at Baresville the numbing thought that they had overshot the mark was wiped away. The blue phantom was ahead of them. Lashed to its small motor boat it was scuttling madly down the river!

Two wet river rats, huddled beneath a miserable shelter, gave the information.

"Yes, mister, a blue houseboat pulled by a small gas boat," they chorused when Blane questioned them.

"Did you speak with them?"

"Yes, mister, a red-headed guy chinned us about gas."

"Did you see a girl on the boat?"

"No, mister. A fat woman was with 'em, but no girl. Leastwise we didn't see none."

Lady Dorothy Carisbrooke made a gesture to Blane as he threw over the wheel. She leaned out and tossed a fifty-dollar bill to the wet outcasts whose information had lifted a great fear from the heart of the five.

Dusk found the Alequippa below Petticoat Ripple. Blane, supported by Haggerty, advised a stop. The river was tricky; the channel narrow and dangerous by Bat and Middle Island. Besides, there was no possibility of seeing the houseboat if she sought shelter and there were few persons abroad who could give information. The Wasp brought the Alequippa into the West Virginia shore and tied up.

The Just-So Kid, who had discovered that Lady Dorothy could not drink black coffee, gallantly offered to walk to a farmhouse about half a mile away in an effort to procure milk, and he started while the others made camp.

The farmer's wife, suspicious of river folk as all the dwellers along the banks of the Ohio are, was wheedled into selling a pint of the precious fluid to Mr. Casey and the Kid started back to the Alequippa.

He had reached a point not more than a hundred yards from the boat when he halted abruptly and dropped to his knees. In the dim light he made out the figure of a man who was scouting cautiously along the ridge that commanded a view of the camp, and the actions of the fellow told the little pugilist that he was not friendly to the campers. He had the air of a Pawnee on a scalp hunt.

The Just-So Kid cached his milk and proceeded to stalk the stalker. Thoughts of the happenings at Steubenville came into his mind. Some one was evidently following the Alequippa down the river in a speed boat with the intention of delaying or crippling the pursuit.

To the mind of the pugilist the fellow on the ridge contemplated an attack. An attack on whom? The Just-So Kid refused to think that any person on the Alequippa outside of Robert Henry Blanc was worthy of such careful stalking. The Texan Wasp was the hero of James Dewey Casey. The tall adventurer from Houston had saved the Kid from starvation at Marseilles in the long ago and had earned his admiration in many ways since that day.

The stalker had spread himself out on the top of the rise in the attitude of a sharpshooter. The poor light made it impossible for the Just-So Kid to see whether the fellow carried a weapon, but he had a firm conviction that he did. The rear view—legs far apart and body resting on the elbows—led Mr. Casey to think that the barrel of a rifle pointed in the direction of the Alequippa.

The Kid crept closer. The unknown's interest in the camp made him deaf to the slight noises that Jimmy made as he crept forward. The belief that the fellow was awaiting a favorable moment to pot some one grew in the mind of Casey. And that some one would surely be Blane.

For an instant as the Just-So Kid wriggled forward he had a view of the Alequippa and the camp. Blane and Haggerty had made a fire and the figure of the Texan was plainly outlined against the blaze.

James Dewey Casey was close to the unknown. Close enough to see the barrel of a ride as the fellow's head snuggled down upon the stock. The Just-So Kid lifted himself and sprang.

Jimmy landed on the sharpshooter's back an instant before the rifle exploded. He landed with a jolt that knocked the breath out of his antagonist. Mr. Dewey's temper was at boiling point.

The man with the gun was no baby. With a grunt of rage he wriggled free and swapped punches with the supple person who had attacked him. The two rose to their feet, slammed each other for a few minutes, then clinched and rolled down the slope. The sharpshooter was a heavyweight and a rough-and-tumble fighter of no mean caliber.

The Just-So Kid had no opportunity to use the uncanny ability of evading punishment that had made him champion of the A.E.F. The other was more of a wrestler than a fighter. He got a strangle hold on the pugilist as they tumbled into a muddy hole at the foot of the ridge, and it was only a question of time regarding the outcome.

Shouts from the camp saved the life of the Just-So Kid. Blane and Haggerty came charging up the slope and the sharpshooter gathered himself up and took to his heels. He plunged down the shrub-covered bank to the river as Blane came over the ridge, and the muffled explosions of an engine shattered the silence.

The Wasp, plunging through the bushes, took a shot at the small speed boat that swung from the sheltering bank out across the darkening river. The shot was returned; a jeering laugh floated back from the water as the boat was swallowed up in the gloom.

The Just-So Kid, revived by Haggerty, told of the happening and Blane listened quietly.

"I guess you saved my life, Jimmy," he said gently. "The bullet from that fellow's rifle lopped off a branch directly above my head. By hopping on his back at the moment he pulled, you spoiled his aim. I thank you."

"Thank me nothing!" snapped Mr. Casey. "If I paid you for everything I owe you I'd be in hock till Judgment Day. Wait till I get a bottle of milk I cached up here."

Unfortunately the fleeing sharpshooter had placed a big boot on the bottle of milk that the champion of the A. E. F. had hidden, and a tiny stream of milk trickled down the hillside.

"Never mind," said Blane, as the Kid poured maledictions on his late antagonist. "I don't suppose Lady Dorothy has any appetite now. Come down to camp."

They kept guard through the night. Only the old nobleman and his daughter slept. Blane, Haggerty, and the Just-So Kid watched the river for an attack.

Robert Henry Blane was doubtful as to the success of the expedition. Staggers' desire for vengeance was rather terrifying. The fellow had nursed his longing for revenge till his soul had become poisoned, and at bay he would think nothing of murder. But to come up with him and fight him hand to hand was the only method available. Ruthvannen's horror of police intervention could not be combated. The Wasp had a belief that the situation had partly deranged the old fellow.

Before dawn, the Alequippa nosed out into the gray mist that covered the river.

A riverman at Stewart's Landing had seen the blue houseboat. A light tender at Brother's Light confirmed the statement. The Alequippa was gaining. The light tender thought that something had happened to the engine of the boat dragging the blue phantom, which had caused them to swing into French Run and make repairs.

"When did they go on?" cried Blane.

"Yesterday afternoon," answered the man. "Couldn't have been more than four o'clock at most."

Four o'clock! The surprised information giver stood and looked after the Alequippa as she tore downstream. He gurgled with astonishment as he noted her speed. Over a bad stretch of water the motor boat was speeding like a destroyer.

At Dam 17, one hundred and sixty-seven miles from Pittsburgh, there was more news. The pursuers were hot on the heels of Mr. William Staggers, one time of Derby, England. The five on the motor boat scanned the shores with unwinking eyes. The quarry would be seeking a hiding place.

They came to Marietta, where the Muskingum River flows into the Ohio. Blane considered the possibility of the houseboat, finding the pursuers hot on her heels, swinging off into the tributary and making upstream toward McConnelsville. He lost precious minutes in questioning the lockmen on the smaller stream. No blue houseboat had gone up the Muskingum.

"There was," said the wizened old man who worked the lock gates, "a blue houseboat below Reppart's Bar this mornin'. Saw her meself."

The Alequippa was speeding downstream before he had finished speaking.

Reppart's Bar lies at the foot of Muskingum Island. It chokes the channel, making it necessary for boats to hug the Ohio shore closely. Below the bar the river runs wide, throwing a backwater up behind the big island which is over two miles in length.

The Alequippa nosed into a landing below the bar, where a barefooted youth stood expectantly. He grinned as Blane hailed him. He was a fount of knowledge. Yes, yes, a blue houseboat had tied up there for the night. Yes, a red-headed man. And a girl. Some looker too.

He hopped aboard the motor boat, took a sheet of folded paper from his pocket and approached Lord Ruthvannen.

"I guess this is for you," he said. "I was told to wait an' give it to you. The red-headed chap give me a dollar for doin' it."

The old nobleman dropped the sheet in his excitement. The Wasp picked it up and placed it in the trembling hands of the Englishman. Ruthvannen made a stammered protest.

"You read it!" he gasped. "I—I am afraid."

Robert Henry Blane opened the sheet and read the message that was scrawled thereon. The handwriting was identical with the writing in the letters from Staggers which The Wasp had read on the way to Pittsburgh. The note ran:

If you foller me anny further ile do in miss evlin so jest cut back agin as smart as you like, we issent goin to be cort. miss evlin knows wot we is goin to do to her if you catches up an it dussen make her grin a bit. ile let her rite a word on this to show ycr wether she thinks it helthy.

Beneath the ungrammatical scrawl came the message from the girl, reading:

Dear Mother and Grandfather: Mr. Staggers is sincere. All your carefulness only menaces. Evelyn.

Blane, as he read the words written by the kidnapped girl, felt a thrill of admiration for her courage and intelligence. The letter "i" in "is" was the beginning of a secret message formed by the first letters of the words that followed. It read: "I say come."

The Wasp drew the attention of Lord Ruthvannen to the brave contradiction, but the old nobleman was in a state of collapse.

"We—we must go back!" he gasped. "We must! We must! He—he will kill Evelyn! He is a desperate man!"

"But Miss Evelyn wishes us to go on!" protested Blane.

"She is foolish!" cried Ruthvannen. "Turn back! She—she will be killed! I—I—"

Words failed him and he sat gasping for breath, his thin hands clawing at his collar. Lady Dorothy Carisbrooke glanced at the Texan. The big brown eyes of the mother seemed to plead for help and advice.

The Wasp looked at the barefooted youth who had brought the note from Staggers, and who had now returned to the landing where he watched with a certain degree of interest the commotion brought by the message. The youth caught the eye of the tall adventurer and winked slowly. It was a wink that suggested information for sale and the Texan sprang from the motor boat to the landing.

"Do you know anything?" he asked abruptly. "Hurry up. Tell me and you'll get paid."

The youth grinned.

"How much?" he inquired.

"Whatever you want," snapped Blane. "Out with it!"

"Will a dollar an' a half bust you?"

The Wasp quickly slipped a ten-dollar bill into the hand of the youth.

"What is it?" he demanded.

"The red-headed chap tried to fool me that he was goin' down the river," grinned the youth. "He made for the dam, but he didn't go through it. He just turned after he got by Briscoe an' came up the river again. He's in behind the island, but don't tell him I said so. He's a bad un."

Blane sprang back to the Alequippa. The old nobleman had recovered his speech and was now more than ever intent upon having his own way. A great and appalling dread of Staggers was upon him. Imagination pictured Evelyn Carisbrooke a victim of the murderous devil who had her in his power.

"Turn the boat around!" he shrieked. "No, no! I will not go into the cabin! I will sit here and see that my orders are carried out!"

Blane conveyed the order to Haggerty. The Alequippa backed out from the landing and started upstream toward Marietta. Lady Dorothy Carisbrooke's sobs were the only protest against the orders of her father.

Blane glanced at the chart. A stone dike blocked the left channel at the top of Muskingum Island, making it impossible to enter the backwater from that direction. And each revolution of the screw was taking him farther from the girl who in the face of death had been collected enough to write a message bidding her friends to take no notice of the madman's threat.

Blane walked astern as the Alequippa headed up by the island. He signaled the Just-So Kid, who came up.

"Jimmy," said the Texan, "I'm going to drop over and swim to the island. If any one asks you where I am, say I am lying down. Tell Haggerty if he gets a chance to hire another boat at Marietta and look me up in a couple of hours. Not before."

"Can't I go with you?" asked the little fighter.

"No, you cannot," growled The Wasp. "Go away now or that old idiot of a lord will think we are playing tricks on him. I never took much stock in the intelligence of folk that wear titles. I would advise you, Jimmy, never to take one."

"Me?" cried the Just-So Kid. "Why I'm a Demmycrat!"

"Beat it!" grinned Blane, as he kicked off his shoes. "Remember what I said. Tell Haggerty to come back in two hours."

The Kid turned and glanced back. Robert Henry Blane, in trousers and undershirt only, had dived into the yellow waters of the Ohio.

THE WASP landed on the upper end of the island, below the

stone dike that connected it with the West Virginian shore.

Through half-submerged bushes and stretches of sticky mud he

crossed the isle to the backwater and then worked his way

south toward the open river.

It was a difficult and unpleasant promenade. At times The Wasp sank to his waist in the tenacious mud; at times he swam across brier-choked inlets covered with green scum. Before his eyes as he pushed hurriedly forward were the three words which Evelyn Carisbrooke had cleverly built into her message.

"I say come!"

He repeated them to himself. They became a slogan. There was something extraordinarily courageous and self-reliant about the statement. Blane had a great desire to see the girl who could send such a command in the face of death. He thought old Ruthvannen a fool.

The stillness that was upon the island was shattered by the report of a revolver. There came another and another. Blane, surprised by the sounds, splashed madly through the mud. Something was happening in the backwater. A great fear clutched him. Had the crazy Staggers carried out his threat?

The Wasp thrust his way through a barrier of bushes and came in view of the navigable section of the backwater. Immediately opposite the point at which he stood, her blunt snout driven into the bank, was the blue houseboat and the little motor boat that had dragged her down the river. The crouching Texan stared at them. They seemed deserted.

Blane slipped into the water and swam across the backwater to a point above the houseboat, where his approach would not be noticed. He landed and crept along the bank toward the blue craft. The silence that was upon the place was a little terrifying. It suggested a sudden elimination of life. It brought a queer quality of horror, of nausea.

On hands and knees the Texan crawled to the forward deck of the houseboat. He dragged himself up and peered within the big cabin.

The place was in wild disorder. It looked as if a tornado had swept through the boat, upsetting everything. The floor was strewn with broken crockery, cooking utensils and battered chairs.

Revolver in hand Blane rushed through the cabin to the smaller compartment at the rear. The matchboard division had been partly carried away by something bulky that had collided with it, and this evidence suggested to The Wasp that the combatants, in the final round of the combat, had crashed through the separating wall and tumbled into the smaller cabin.

His surmise was correct. Upon the floor, locked in a death embrace, were two men, their unshorn faces pressed close to each other, their legs intertwined. Upon the breast of one, black and vicious looking, lay a snub-nosed automatic that resembled a Gaboon viper attempting to warm itself on the body of a victim. It had dropped from the lifeless fingers of its owner.

One glance told Blane that neither of the men resembled the description he had of Staggers. William of the gangrened soul was not there. Neither was the girl, Evelyn Carisbrooke, or the fat woman that had been reported on the boat.

After a quick glance at the stern deck of the houseboat and the empty cockpit of the speed boat, the Texan dashed back to the nose of the blue craft. He sprang to the bank. Tracks showed in the mud, tracks that led southward in the direction of Briscoe.

Running with body bent double, Blane followed the trail. The heavy prints of a man's shoes showed beside those of a woman's that left nearly as deep an impress in the mud, while beside the two were hardly discernible marks that told of the passing of some light-footed creature shod exquisitely.

The trail swept up the bank. It was lost in the grass. Like a questing hound the Texan ran up and down seeking it. A scrap of paper caught his eye. He pounced upon it. It was part of a leaf from Knight's book on "Small-boat Sailing," the book from which Evelyn Carisbrooke had torn the page on which she had pricked the message that had been found at Rush Run.

Twenty feet farther on Blane found another scrap. He understood! The girl had not lost her head in the dreadful circumstances. Possibly foreseeing a flight from the houseboat, she had torn up leaves of the book and thrust them into her pocket. These she was dropping at intervals to guide her rescuers.

The trail was difficult. The trio had forced their way through thickets, holding close to the bank of the river; Staggers evidently afraid to make a break across the road and the electric line connecting Marietta and Parkersburg.

Blane burst through a clump of bushes into a bare bluff immediately above the river. A growl like that which might come from the throat of a wounded beast halted him. Standing on the extreme edge of the bluff, a straight drop of some twenty feet between him and the yellow waters, was Staggers, holding with his right arm a tall girl whose brown eyes, large like those of her mother, were fixed upon The Texan Wasp.

Staggers spoke in a thick voice.

"Not another step!" he growled. "Another inch an' we go over together!"

Blane, gun in hand, stared at the two. The big, red-headed man clutched the slim girl so that her feet were off the ground. Her weight seemed nothing to him. He swayed backward and forward within a few inches of the abyss.

Mr. Staggers was not a pretty sight. A wound on his forehead was bleeding.

The eyes of the Texan examined the face of the girl. He could see no trace of fear. She waited patiently, seemingly prepared to accept anything that might come to her.

There was an interval of silence, broken only by the sobbing of some one who was crashing through the bushes in the direction of the road. The fat woman was escaping.

Blane, gray eyes upon the wound on the forehead of Staggers, spoke.

"It will do you no good to jump into the river," he said quietly. "It will not harm Miss Carisbrooke."

A murderous grin appeared upon the face of the man. His right arm brought the supple form against his body with a jolt that startled the girl.

"Won't it?" he asked. "If she can get clear of me before I choke the life out of her, she's a good un. Bill Staggers is goin' to get even with the ole blighter that gave him a ten stretch in the jug."

Blane sighed softly. Ostentatiously he started to put away his revolver. He thrust it into the leather belt around his waist, then, apparently dissatisfied with its position, he pulled it out again, the red eyes of the madman watching him intently.

The Texan seemed to consider the matter of the revolver, glancing at it as it lay in the palm of his right hand, then, as if he had suddenly made up his mind as to where it should go, he swept it toward the back pocket of his trousers.

The movement was followed by an explosion. A look of intense agony appeared on the face of Blane, for an instant he stood upright, horror showing in the gray eyes, his mouth open, then he crumpled and fell forward, face downward. The girl screamed.

Bill Staggers loosened his clutch on the girl so that her feet touched the ground. He took a step forward, another and another. His red eyes were upon the gun that had exploded as Blane was thrusting it into his pocket. A grin of delight showed on his face as he stooped.

Something that had the clutching power of a thousand tentacles shot out and gripped the ankle of William Staggers. He was jerked from his feet and, as he fell, one hundred and seventy pounds of Texan manhood rolled on top of him. A fist ripped upward to Bill's chin and the affair was over.

THE sobbing Miss Carisbrooke, sitting on the grass,

watched Robert Henry Blane tie up the madman. He did it neatly

with the aid of Mr. Staggers' belt, then he seated himself on

William and looked out across the river. Round the foot of

Muskingum Island came the Alequippa.

The girl spoke after Blane had pointed to the boat.

"You—you Americans are so practical," she murmured.

"There's a little fellow on the boat that you'll like," he said. "I had a difference of opinion with your grandfather and I told this chap never to take a title and he said he couldn't, because he was a Demmycrat."

Evelyn Carisbrooke smiled. "Some of the titled people are silly old beans," she said softly. "I—I think I'd like to stay all my life in America."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.