RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

The Ladies' Home Journal, April 1918,

with "The Man in the Smoker"

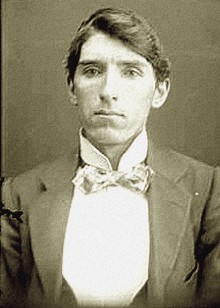

James Francis Dwyer

JAMES FRANCIS DWYER (1874-1952) was an Australian writer. Born in Camden Park, New South Wales, Dwyer worked as a postal assistant until he was convicted in a scheme to make fraudulent postal orders and sentenced to seven years imprisonment in 1899. In prison, Dwyer began writing, and with the help of another inmate and a prison guard, had his work published in The Bulletin. After completing his sentence, he relocated to London and then New York, where he established a successful career as a writer of short stories and novels. Dwyer later moved to France, where he wrote his autobiography, Leg-Irons on Wings, in 1949. Dwyer wrote over 1,000 short stories during his career, and was the first Australian-born person to become a millionaire from writing. —Wikipedia

The little man in the smoker hadn't much to say at first— he just listened to the talk of the one with the upturned mustache. But when he did speak he said something—something that did all the others in the smoker good tp hear, something that will do you no less good to read.

"YES, sir, they have been preparing for this war for more than forty years."

You, too, fellow citizens, have listened to this statement. You have heard it often. On this particular occasion the words, uttered in a loud voice, roused me from a doze and I sat up and looked around me at the four occupants of the Pullman smoking-room.

I looked at the man who had made the remark which roused me. There was something in his voice that was not entirely pleasing. He had proclaimed the forty-year preparation in a voice that made me think he was a little wee bit proud of the Hun's foresight, a wee bit inclined to shout the news in the belief that it would act as a deterrent, as a courage-cooler, to any one prepared to shoulder a rifle for civilization.

He was a hearty, round-faced person, wearing a big mustache that had a slight tilt at the ends. I had a vicious desire to question him about his nationality. Perhaps I was wrong, but—He repeated the words as if for my benefit:

"That's right, gentlemen; they've been preparing for this war for over forty years!"

Again the undernote, the curious threatening subtone, the "mind-what-you're-doing" advice that was but dimly sensed and yet surely there.

There was a small, undersized man wedged into a corner of the leather seat.

"And what have we been doing for forty years?" asked this little man.

"You mean the United States?" queried the fat person.

"I mean my country, the United States of America," answered the small person.

"Why you—that is, we've been doing nothing!" roared the big fellow. "Absolutely nothing! We've sat still and let the others prepare. We've believed foolishly in peace, and now when war has come we're a helpless nation that doesn't know which way to turn."

There was a silence for a few moments after the fat man made this assertion. Then the little fellow in the corner drew out a silver watch, studied it carefully and, still looking at the watch, made an observation.

"I've got twenty-five minutes before I reach my getting-off place," he said quietly. "And if no one has an objection to make I'd like to tell what my country, the United States, has done to prepare for war. That is, I'd like to tell of the things that have come under my own personal knowledge."

The man with the stiff mustaches smiled.

"Go ahead," he said in a manner that showed how utterly impossible he thought the task which the little fellow was attempting. "I'd like to hear what this country has done to keep a strong foe, a strong foe like the Germans, from jumping her."

The small man elbowed himself to the edge of the seat, glanced around him at his audience of four, and began speaking in a quiet voice that possessed a strange, sooth ing quality.

"I am a Swede," he said. "So is my wife. We came to New York in the year 1889.

"I couldn't speak English, neither could my wife. It was a drawback. I had no trade. I was just a plain laboring man from Upsala, and when I was offered a position as janitor in an apartment house on Washington Heights, I jumped at the offer. The wage was twenty five dollars a month, with the use of three rooms in the basement.

"My oldest boy, Christian, was born in the basement of that house on One Hundred and Thirty-seventh Street. So was my second boy, Sigurd, my youngest boy, Henrik, and my daughter, Hilda. All of them. One child a year was born to me during my first four years in the United States.

"When Christian was old enough to go to school, I took him round to Public School 186, on One Hundred and Forty-fifth Street. I saw the principal, a nice man. He took Christian and me into his office and he questioned me. I could not speak English very well, but it didn't matter. Not with him.

"'What do you do, Mr. Sigbold?' he asked.

"'I am a janitor,' I answered.

"Well, Mr. Sigbold,' he said, 'we will do the best for little Christian, and when your other children are big enough to come to school, we will look after them too.'

"Gentlemen, that schoolmaster kept his word. My children were everything to me, and he had them in his keeping for nearly half of their waking time. That schoolmaster had them in his care all day, teaching them and molding their characters.

"I learned to speak correct English from my son, Christian. He taught my wife and me. I learned from him of George Washington, of Abraham Lincoln, of Nathan Hale, of Grant, of a thousand others. He got it at the school, got it from the principal who didn't care whether I was a janitor or a barrister, and whose only duty was to teach boys to be good citizens.

"They made my boy, Christian, flag-bearer at the assembly exercises. Have any of you gentlemen witnessed those exercises? No? Well, the boy who is picked to carry the flag marches with it down the aisle, and the whole school stands and salutes it. And my boy, Christian, became flag bearer. I went over one morning and saw him, and I cried. Afterward I got into one great big row because a woman on the first floor reported that there was no steam-heat.

"The landlord sent for me and asked me where I was and I told him.

"'My boy was made flag bearer at the school,' I said, 'and I went over to see him carry the Stars and Stripes at assembly. I got so hot and excited I forgot the steam-heat.'

"'Well, don' t forget again, Sigbold,' he said. *The tenants haven't got the luck to have sons who are picked as flag-bearers, and they are cold.'

"Christian graduated, gentlemen. He won a medal for history, my Christian, and I was there, there on the platform when it was presented to him. He brought it to me and his mother to look at, and the principal of that school saw us. He took me over and introduced me to a member of the Board of Education, me who was only a janitor and who had learned to speak proper English from my boy. Listen to me a little while and I will tell you what this country, this United States, has done to prepare for war!

"I cried that evening! Yes, sir, I'm not ashamed to acknowledge it: I cried! It was a gold medal presented by that commissioner that I had been introduced to, and my son had got it! My son, Christian! And I was a Swede, a laboring man from Upsala, who was working as a janitor!

"Wait! That commissioner wrote Christian to come and see him. Christian put on his best clothes and went down to his office in Cedar Street.

"'What would you like to be?' he asked Christian.

"'A lawyer,' answered Christian.

"'Very good,' said the commissioner. 'My brother will take you into his office. Take this note around to this address in Liberty Street and you can start right away.'

"My boy, Christian Sigbold, earned last year over thirteen thousand dollars. He is a junior partner of the firm that he went to work for as an office boy on that day."

The fat man with the big mustaches yawned and patted the stiff bristles with a huge, white palm. He seemed a little bored with the Swede's story; but the Swede, after another glance at his watch, continued:

"My second boy, Sigurd, also won a medal when he graduated. He recited a poem—Paul Revere's Ride. It was wonderful to me. I did not know of Paul Revere till my boys told me about him. But, gentlemen, the night that Sigurd recited I sat there with little thrills racing up and down my spine. You see——"

The fat man grew impatient and interrupted with a wave of his big hand. "But all this has nothing to do with what I said," he remarked irritably. "I stated that this country has made no preparations for war. She has sat quietly believing in the fool doctrine of peace, and now she is not equal to the task of protecting herself against a strong foe."

"Perhaps you think so because you like to think so!" snapped Sigbold. "Wait till I finish and I'll tell you what she has done! Wait!"

The big fat man subsided. There was something strange about the fierceness of the little fellow. I doubt if the other two listeners had the slightest idea of the dramatic climax that he had ready for his narrative. I know that I had no thought of what it would be. I, like the big man, believed that he was an overproud parent who was ready to seize any opportunity to tell of the success achieved by his children.

"My boy, Sigurd, became a doctor, helped by that principal. He is a specialist. He is young, but he is well known. I am his father and perhaps it is wrong for me to boast, but I might be pardoned for telling you that a special train took him from New York to Chicago a few months ago so that he could perform an operation on a millionaire's baby who was dying from diphtheria.

"Henrik also became a flag-bearer in that school. He loved it. Strong as a young bull he grew, and when he walked down the aisle carrying the silk flag you would think he was a young Crusader. He graduated and be came an architect—Sigbold & Farrance is the firm, gentlemen. Mr. Farrance is my son-in-law; he married my daughter, Hilda. His father is from Christiania and he was educated at the same school as my sons."

The little man stopped, looked again at the silver watch, then got to his feet. The porter, armed with a whisk-broom, entered and, singling out the little man, led him to the door and started to brush him vigorously. I glanced at the other listeners and they, in turn, glanced at me. We were puzzled, the big fat man more than any of us. This amazement was so great that his lower jaw had dropped and a cavernous mouth showed beneath the Kaiser-like mustaches.

The train was slowing up and the fat man pulled himself together with an effort. "That's all very well," he cried; "you've fooled us into listening to a little history of your children. What's that got to do with preparing for war?"

"Do you know what place this is?" asked the little man quietly.

"No," answered the fat man.

"Well, it's the nearest station to one of Uncle Sam's biggest camps," continued the little man quietly. "And I have three sons and a son-in-law in that camp, sir! I told you my boy Christian was earning thirteen thousand dollars a year? He's here as a private on thirty a month. Sigurd, who had a blank check given to him by the millionaire whose baby he saved, is here in the medical corps, and the firm of Sigbold & Farrance is out of existence. Both of them are here, designing trenches instead of Queen Anne villas!

"The old United States has not been asleep during the last forty years, gentlemen. She has been preparing, but preparing in a different way from the Huns. Instead of stripping her children of their self-respect, she has buckled on them an armor of pride like that which she buckled on my boys, and all hell can't lick 'em! Do you hear me, gentlemen? All hell can't lick 'em!"

The porter brought the little chap's bag and he stepped into the passage with a farewell nod. The two other men and myself followed him to the car platform and watched him descend. Before he had climbed down the steps a husky quartet in khaki sprang at him, dragged him to the ground and carried him off bodily, howling and shrieking with delight as they tramped away.

"Gee," said one of the men standing at my elbow, "they're big soldiers! I suppose they're the little fellow's three sons and his son-in-law."

"I suppose so," I said. "If that fat man could see——"

The man who had commented on the size of the soldiers gave my arm a warning touch and I stopped speaking. The mustached person, who in the beginning had loudly proclaimed the foresight of the Hun, was staring after the little fellow and his husky escorts with a look of puzzled wonder upon his face.

The train began to move, and the three of us stood there in the vestibule, noticing a number of stalwart figures in khaki as we slid past the platform.

"Well," I said—for the aggressiveness of the man had irritated me—"I guess there may be something in our friend's kind of preparedness, after all."

He grunted, and as the porter closed down the steps he turned away into the car. Then, in an abrupt, harsh way he wheeled round and spoke to the attendant.

"Is my bed made up?" he asked. "It is? Then I will go to bed at once. I feel very tired."

The man who had touched my sleeve turned and winked at me.

It was enough to make a Prussian feel tired!

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.