RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a print in "Vanity Fair," 1 March 1879

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a print in "Vanity Fair," 1 March 1879

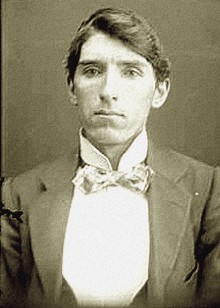

James Francis Dwyer

JAMES FRANCIS DWYER (1874-1952) was an Australian writer. Born in Camden Park, New South Wales, Dwyer worked as a postal assistant until he was convicted in a scheme to make fraudulent postal orders and sentenced to seven years imprisonment in 1899. In prison, Dwyer began writing, and with the help of another inmate and a prison guard, had his work published in The Bulletin. After completing his sentence, he relocated to London and then New York, where he established a successful career as a writer of short stories and novels. Dwyer later moved to France, where he wrote his autobiography, Leg-Irons on Wings, in 1949. Dwyer wrote over 1,000 short stories during his career, and was the first Australian-born person to become a millionaire from writing. —Wikipedia

THE JUDGE limped slowly from his room and took his seat. A thousand eyes, restlessly searching the courtroom for interesting food for morbid minds, concentrated on him. The judge felt the many-eyed stare like a thousand shafts of light playing over his face, and he tapped nervously on his desk.

The attorney for the people, obsequiously polite, leaned forward and informed the judge that a slight accident had delayed the arrival of the prisoner and the most important section of the great machine of justice that was piecing itself slowly together was visibly annoyed. Till the trial started, he would be the focussing point for the thousand hungry eyes, and he was afraid—afraid lest his face might twitch under the fusillade of pain shafts that came from his right foot. The judge had a bad attack of gout.

The silence was impressive, and the pain in the judge's foot, as if annoyed at the fixed judicial frown, that steadfastly refused to allow the face to acknowledge the agony, increased. Hot, piercing thrills raced up his leg, and his brow oozed moisture under the attack. The foot throbbed; he pictured it swelling. Then followed a procession of pain spasms. His teeth gritted, while three great welts between the small eyes, like marks left by a blunt axe, grew more noticeable.

The thousand eyes studied the judge. Their gaze crept over the brutal face, noting the lower jaw that protruded like a bulldog's; the flattened nose pressed against the face as if it would give the mouth an opportunity to snap at anything that came near; the low-set ears; the shifty eyes, and the curious half-circles of smooth, white skin that ballooned up beneath the eyes and carried a livery message to sharp observers.

Three newspaper artists took the lower jaw as a base and built up an acute-angled profile upon it, and the judge noticed the straying pencils. His eyes, sensitized by pain, photographed a thousand details.

The prisoner arrived at last. He was a small, nervous man with a weak face. The sheriff pushed him roughly forward, by that means indicating him as the cause of the delay. The prisoner stumbled into a seat and blinked at Justice with the bandaged foot.

The judge was relieved. He heard the shuffling of the five hundred as they turned their eyes on the new attraction, and he allowed a procession of pain spasms to flit across his face in acknowledgment of the extreme agony in his foot. At that moment the prisoner was the only person watching the judge, and the prisoner thought that the pain ripples passing over the face of the great one were caused by disgust stirred up by his (the prisoner's) appearance. But the nervous wretch, whose doings the machine intended to analyse, knew nothing of the bandaged foot resting uneasily on its cushion beneath the desk.

The interest became more evenly distributed over the different parts of the machine. The attorney for the people and the attorney for the defence shuffled great bundles of papers. The sheriff coughed loudly. The jury whispered, and the great instrument of justice got under way. But the pain in the judge's foot increased. Patches of ashen-gray rushed across his face, smothering the usual ruddy tint that returned when the pain abated.

The prisoner was charged with burglary. A house in the suburbs had been entered, and circumstantial evidence swirled like a ghostly rope around the man before the court. The attorney for the people moved to the attack with a languid, confident air that induced the more vivid imaginations in court to dash forward and fix the penalty. The tired listless voice as he cross-examined carried a message to the court. It said: 'It is immaterial all this talk; we know that he is guilty, but we must give him a fair trial. The greatest scoundrel in the land can demand a trial before a jury of his countrymen.'

And while the prisoner listened to the languid questions, his eyes watched the judge's face and he wondered. For the judge's foot was in a bath of molten lead that made him deaf and blind and heartless.

'And you were awakened by a sound?'

The attorney for the people was examining the occupant of the house that had been entered.

'Not by a sound,' smiled the witness. The questioner turned hastily to his papers, the smile of the questioned one informing him that he had strayed from the text. Not finding the information he required, he straightened up with a well-it-doesn't-matter air and propounded an-other question.

'What awakened you then?'

'Somebody grasped me by the foot,' replied the witness.

The judge started. The ruddiness faded away for half a minute. When it returned he addressed the witness.

'What did you say?' he snapped.

'I was awakened by someone grasping my foot,' answered the householder.

The protruding under-jaw tucked itself back till the half-circle of short teeth gritted under the top row. Usually the lower teeth came up in front of the upper set.

'By—the—foot?' gasped the judge.

'By the foot,' repeated the witness, smiling easily at the astonishment visible on the broad face. The smile annoyed the gouty one.

'What is there to smile at?' he cried angrily. 'Why did he grip—never mind, that's enough.'

The attorney for the people, too polite to exhibit any surprise, stood waiting, but the judge motioned him to continue the examination. The startled witness had little to tell. He pursued the figure that sprang through the window, but the night swallowed the shadow, and he returned to his couch. He could not identify the prisoner before the court. He had never seen him before. The man he pursued appeared to be taller than the prisoner.

The attorney for the people sat down, and the attorney for the defence arose in his place. The witness was really favourably disposed to the prisoner, and there was no necessity to cross-examine, but the interest displayed by the judge in the leg-gripping incident led the attorney to think that a little probing round that particular spot would impress the court.

'You are sure your foot was gripped by someone?' he asked, a humorous smile drifting over his fat face. The gray clouds of agony swept over the features of the judge. The pain in the right foot was intense.

'Certainly,' replied the witness.

'You were not dreaming?' questioned the attorney. He had no definite idea as to how this line of questioning would benefit his client, but he knew that it would keep him before the eyes of the spectators. It enabled him to liven up the proceedings. He was twisting a bright thread into the drab web the machine was spinning. He knew that the humorous part of the cross-examination and the name of the person who extracted the humour would be remembered by the listeners when everything else connected with the case was forgotten. He was a cute advertiser, this attorney. He considered that a joke in court was worth two outside.

'No, I was not dreaming,' answered the witness.

'Did you wake suddenly?' asked the attorney. The foot of the judge and the mind of the judge compared notes. The foot wanted to know if the judge would wake suddenly if a night-prowler gripped the gouty limb in a great, hairy hand, and the judge, sweated in agony. The mind pictured the sensation, and the stubby hands of the judge snapped the handle of his pencil.

'Well, no,' drawled the witness, 'I did not wake suddenly.'

He had previously informed the court that the person who had so rudely disturbed him had sprung through the window before he left the bed, and he recognised that a slow awakening would be the supporting pillar beneath that detail.

A point showed up on the attorney's mental horizon. He straightened up and took a large breath of the hot air. He covered the witness with a fat forefinger and the witness looked startled as the fleshy Colt threatened him.

'Now,' if anyone gripped your leg,' thundered the questioner, 'gripped it hard—wouldn't the effect be immediate?'

The judge's face rippled with pain waves. The possibility of such a happening provoked the right foot to its extreme agony-producing limit. The prisoner was hypnotised by the expression on the broad face, but the others were watching the jester. The witness hesitated a moment before answering the question put to him, and the attorney, thinking he had him corralled, repeated it with pantomimic action so that all might see how cunningly he could throw a verbal lasso.

'If anyone,' he said, slowly reaching out a strong hand towards the witness stand, 'gripped your leg like that, would you jump?'

The judge watched the hand coming slowly in his direction. When it closed on a handful of hot air with a snap that proved the attorney's muscles were stronger than his line of cross-examination, the judge jumped. The movement made him set his teeth quickly to strangle the shout of agony. The foot had touched a little projection beneath the desk. He swallowed hard.

The five hundred spectators co-operated in a gurgle of approval. The reporters and the jurymen smiled. Even the attorney for the people, who was gazing at the ceiling and spinning a mesh for the leading actor in a murder case that would follow the case then before the machine, allowed his lips to move back from the white teeth and then spring together again in a way that suggested an elastic band running around the mouth. Only the judge and the prisoner missed the humour.

The attorney for the defence felt that he had scored. The suppressed gurgle put an inch on his stature, and three inches on his chest expansion. The witness did not answer the inquiry, and he ventured to repeat the act. The attorney was a fool. It is only the wise who know when to leave off. Again the muscular hand crept forward with the fingers bent to a nice leg-embracing curve. Again the judge watched it. The veins on his forehead swelled up and mopped the red brow into irregular sections till it resembled a land map. The foot flamed.

'If a man—a strong man,' roared the attorney, 'gripped—'

'Stop! Don't!' The two words shrieked by the judge rushed through the courtroom, found the door, and fled down the street chased by a thousand echoes. The attorneys, jury and spectators sat in an air of weird expectancy. What was wrong?

The judge swallowed convulsively. The lower jaw moved up and down, waiting for the words choked back by pain. He glared at the attorney—a fixed, fierce glare that pushed that person back into his seat. At last he spoke.

'What do you mean by this nonsense?' he screamed. 'What do you mean by annoying the court—yes, sir, annoying the court with this buffoonery?'

The attorney gripped the table and attempted to pull himself into an upright position against the influence of the judge's fierce look.

'I only—' he stammered.

'Silence!' roared the judge. The foot was swelling. Flashes of pain spurted up the leg. The pencil of an imaginative cartoonist moved rapidly, and he muttered to himself. 'They won't believe this is like him,' he said, as he dashed in a few strong lines. 'Gee! I'm glad I can get a living out of this. I might be tempted to do a bit of burglary.'

The pain eased for a moment, and the judge spoke.

'Are there any more questions to be put to this witness?'

The obsequious attorney for the people answered in the negative, but the attorney for the defence did not reply. He pushed the case from his mind, and started to overhaul the injuries done to his pride. In the pain of his own martyrdom he forgot his client. It was unlucky for the prisoner. The polite attorney for the people, who did not indulge in buffoonery, made the ghastly rope that swirled round the prisoner more tangible in the eyes of the jury. He put questions to witnesses that he should not have put, but no one objected. The attorney for the defence had the corpse of pride within his mind; the judge was thinking of the flaming foot.

Conviction was sure. One felt it. Strangers who had not heard a word of the evidence put their heads in at the door, and immediately became aware that the law had its victim in a corner. And the prisoner sat staring at Justice with the bandaged foot. Young reporters winked at each other and made guesses.

'Two years,' whispered one sitting near the cartoonist who had snapped the judge's passion face.

'Three!' breathed the cartoonist. 'Did you see the guy's face when he dressed Peterson?' But the other scribbled 'Bosh' in caps, on a sheet of paper. Two years was about the average expected by the 500 spectators.

The two attorneys made brief addresses. The attorney for the people used short cold sentences. He was thrifty of words. He had just returned from a hunting trip in the North-west, and again he felt the fierce joy that comes to the successful thrower of the lasso. The attorney for the defence slobbered. His sentences sprawled. He was on slippery ground. He missed many good points. He remembered that the householder said the man he pursued appeared to be taller than the prisoner, but he did not mention it to the jury. His voice sounded like a dirge.

The judge summed up with a perfect storm of pain arrows shooting up his leg. His sentences were verbal bombs that smashed the defence to atoms. The imaginative cartoonist watched him closely, and put in a few more strokes to his unfinished sketch as the jury re-tired to their deliberations. They returned in eight minutes. The mind of each had been seared with the one word—Guilty—long before they left the court. The foreman handed up the verdict with a sigh, and dropped back in his place as the prisoner moistened his lips to make a plea of mercy to the Gouty One sitting above him.

'I'm the man, judge,' he gurgled, piteously. 'I'm the man who was in the house, I was starving, judge. I went through an open window, but I took, nothing. That's truth. As sure as God is in heaven I took nothing. Don't be hard on me, judge—don't go hard on me.'

The judge's foot used up a little bunch of red-hot arrows with the speed of a Gatling. He wondered how he could limp out of court.

'Why did you grip the man's foot?' he roared.

'I stumbled, judge, whined the prisoner. 'I stumbled, and I put out me hand. I did, that's a fact.'

The judge paused. The agony of the foot turned him sick. The prisoner remembered the little incident of the cross-examination, and attempted to put in a few more words of explanation.

'I stumbled over the carpet an' grabbed him by the foot—'

'Silence!' screamed the judge. An ashen patch held the usual ruddy tint at bay. Beads of perspiration glistened on the bushy eyebrows.

'Prisoner,' he thundered, 'I sentence you to ten years' imprisonment.' The prisoner fell back on his seat, the spectators gasped, and Justice with the bandaged foot limped painfully to his room.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.