RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Munsey, February 1916, with "Hulbertson, Outcast

James Francis Dwyer

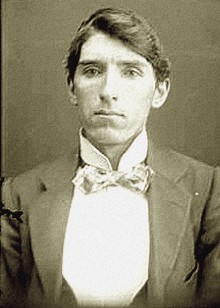

JAMES FRANCIS DWYER (1874-1952) was an Australian writer. Born in Camden Park, New South Wales, Dwyer worked as a postal assistant until he was convicted in a scheme to make fraudulent postal orders and sentenced to seven years imprisonment in 1899. In prison, Dwyer began writing, and with the help of another inmate and a prison guard, had his work published in The Bulletin. After completing his sentence, he relocated to London and then New York, where he established a successful career as a writer of short stories and novels. Dwyer later moved to France, where he wrote his autobiography, Leg-Irons on Wings, in 1949. Dwyer wrote over 1,000 short stories during his career, and was the first Australian-born person to become a millionaire from writing. —Wikipedia

IT was a remark made by Baxter, the big American, that brought the story. Baxter, with O'Neill, the captain of the Maori Belle, Lawrence, the supercargo of the same vessel, and Hulbertson, lay on the sandy beach of Yaon and talked. It was a moonlit night. Away to the right the cliffs rose up nearly perpendicular, and upon the very edge of the wall of rock clustered the palm-thatched huts of the natives.

Hulbertson's little coral-limed shack was close to the shore, not more than twenty feet from the spot where the four men lay. The soft light from the slush lamp came through the open door and fell upon the gray-headed beach-comber as he reclined upon the sand.

Baxter had spoken of the loneliness that was upon the island. He had rounded off his remarks by putting a question to Hulbertson, who was known from Flinders Reef to the Paumotus by the somewhat ironic title of "the Marquis of Yaon."

"How can you stand it, Hulbertson?" asked Baxter. "Why, this loneliness is like a cold hand that chills one. It would drive me crazy!"

"I have become used to it," said the beach-comber. "I have been here nineteen years."

A native woman, carrying a bottle of whisky and four chipped cups, came from the little shack. She was a woman of middle age, yet there was a suppleness about her that gave her a look of surprising youthfulness. She had much natural charm, and she moved gracefully.

Hulbertson looked up at her, made a signal with his hand, and she brought the whisky-bottle to his side. Again he made signs with his fingers; the woman went quickly back to the house and returned with two young coconuts, the tops of which had been neatly chopped off.

After Hulbertson had put whisky in the four cups, she filled them with the liquid from the coconuts; then she looked at the man in the questioning, strained way in which a person unable to hear looks when expecting an order. Again Hulbertson signaled to her, and with a little curtsy to the other men, she returned slowly to the shack.

The woman was the beach-comber's native wife. She had been deaf from childhood. She adored Hulbertson, who was a man so much out of the common that an observer could easily see why the title of Marquis of Yaon had been conferred upon him. He had a fine-shaped head with particularly good features. The nose was splendid; the eyes—deep-set, flashing, blue eyes—were possessed of much intelligence; the mouth was firm and handsome. The beach-comber's hands were so attractive that Baxter stared at them when Hulbertson handed round the drinks.

The four lifted their cups and drank in silence. Then the beach-comber spoke.

"I had been here just two years when you made your first call, O'Neill," he said.

"Yes, I remember well the first day I put into Yaon," said the captain of the Maori Belle. "That was seventeen years ago."

"So you have camped here nineteen years!" said Baxter. "Nineteen years on an island that a man can walk around in half a day!"

There was silence after Baxter spoke. The three watched Hulbertson. He was not the ordinary beach-comber. He had not degenerated into a rum-drinking sot, although he was tied up to a native wife. He was always clean and presentable, and, wonderful to relate, he shaved daily.

Suddenly the beach-comber turned upon Baxter and spoke.

"Would you like to know why I am here?" he asked in a quiet voice. "Would you?"

"Sure," said the big American, lifting himself on his elbow. "I would like very much to hear the story."

FROM the hut came the voice of Hulbertson's wife softly crooning a Tongan love-song. From the beach came the hiss of the little waves that flung themselves upon the sand, which shone milky-white in the moonlight.

Hulbertson spoke.

"I came down here from Singapore," he said, "by way of Rabaul and the Carolines. I was tired of the big centers of the world, and had a mad longing for sand and surf, palm-trees and silence. It was a sort of spring longing, but in my case it had become chronic. Every normal man gets the longing when the sap goes up the trees, and I got it so infernally bad that it ate away the veneer of civilization and made me a savage. I hated my own kind. I hated crowds, cities, and I had to cut loose.

"I got down here, and I liked it. Neena was the chief's daughter. She liked me, I liked her, although she was deaf, and we were married. I had put the world and its worries out of my head, and I settled down to spend my days free from all cares. These little green patches were the Islands of the Blest to me. The song of the surf upon the beaches, the lullaby that the south wind sings to the palms, and the little patter of the rain-drops on the thatched roof, were so many lariats that bound me to the place."

The beach-comber paused. He stood up, took a dozen strides along the sand, then returned to the spot where he had been sitting. The three listeners watched him as he took the short turn, and it was then that the captain of the Maori Belle noticed how awkwardly Hulbertson moved. The beach-comber was of athletic build, yet he walked with a curious, disjointed motion of the knees which puzzled O'Neill.

"I was here twelve months when a yacht sailed in and anchored out there beyond the reef," said Hulbertson, continuing his story. "I remember the day well. It was a sunny day in spring, and I was lying on the top of the cliff, up there where the village is. Neena and I lived there then.

"I sat watching the yacht. I knew that she was not a trading vessel. She was a pleasure yacht, and I didn't view her arrival with any great enthusiasm. She sent ashore a boat manned by four sailors, and in the boat were two men in white. They asked a few questions of the natives on the beach, and I saw the boys pointing up to the top of the cliff, where I lived. You know the path leading up the face of the rock? Well, they started to climb it, and I wondered as I watched them.

"Neena came out and stood beside me as they clambered up that nearly perpendicular trail. She was watching them closely, and she turned and asked me a question.

"'Who are they?' she said.

"'I don't know,' I answered.

"'I am afraid of them,' said Neena.

"'Why?' I asked.

"'Because I think they have come to take you back, she said. 'Something tells me that they have.'

"Now that was strange, when I tell you of what happened. Those two climbed up and up till they reached the top of the cliff. The boy who was acting as their guide pointed to me, and the two walked toward me. Neena had taken hold of one of my hands, and she was holding it tightly.

"'Good day,' I said. 'Do you want to see me?'

"The older man of the two took off his cap and bowed.

"'If your name is Hulbertson,' he said.

"'That is my name,' I answered."

Again the beach-comber halted. The silence seemed to grow more intense. It irritated Lawrence so much that he tried to hurry the story-teller.

"What did he say when you told him it was your name?" he asked.

"What did he say?" repeated Hulbertson slowly. "He said something that jolted me hard. He said something that took me away from the palms and the beaches and the blue surf, and I saw St. James's Park, the Row, Piccadilly on a sunny morning, and the sweet-smelling uplands of Surrey. I saw England, my England! Those pictures, a million of them, came up within my brain like an overexposed photographic plate that has been dipped into a strong developing solution.

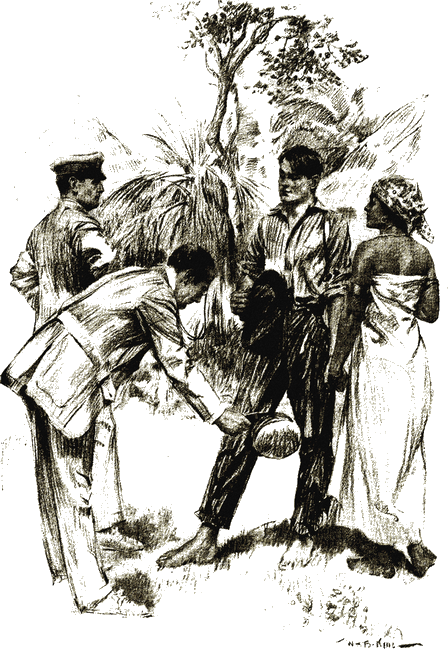

"The elder of those two men stepped forward and bent himself nearly double.

"'I salute you, Sir Hugh!' he said. 'I am very much pleased to be the first to tell you of your good fortune.'"

"I salute you, Sir Hugh! I am very much pleased

to be the first to tell you of your good fortune."

"Isn't it strange how a man can be twisted around in a moment? Some unexpected happening will unloose a mad riot of feelings that he hasn't been aware of. That's what that man's words did to me. I had been feeling contented, satisfied, but when he spoke a wild nostalgia sprang upon me. The longing burst out from some chamber in my brain, and I was crazed with a longing for home, for home!

"I knew what had happened when he called me by that title. When I sailed from Southampton two years before, there were three between me and that little prefix—three healthy people, and the most optimistic money-lender in London would not have loaned me a sovereign on my chance of ever getting it. Stupidly I listened to what he told me. Fate had made a clearing up. Two of the three were drowned together in the Solent, during the week of the regatta at Cowes; the third met a bull elephant in a temper somewhere out at the back of Nairobi, and his remains were unrecognizable. Those things happen now and then.

"It was when the three were wiped out that they started to hunt for me. They traced me to Port Said, to Suez, on through Aden to Bombay, and from Bombay down to Colombo. They lost me there, but four months later they picked up my track at Rangoon, and followed me down through Banjermassin and Rabaul, till they located me at Yaon. The elder man was the family solicitor; the other was the captain of the yacht—my yacht!"

HULBERTSON lifted his voice when he cried out the words "my yacht," and the taunting echo was thrown back by the cliffs. It seemed as if the very rocks were amazed to hear the beach-comber of Yaon talking of his yacht.

"I needn't tell you about our conversation," Hulbertson continued. "I needn't tell you how much the estate was worth. There was a cozy place with shooting and hunting down in the Midlands, a town house near St. James's Park, and the yacht; that was all—that and the title. Sir Hugh Hulbertson! Nice load for a beach-comber of Yaon, eh?

"But I wanted to go back. Yes, I did! I was crazy to go back. Neena was nothing to me when that homesickness clutched me. Yet I didn't want them to see me take leave of a native woman. I guess you understand. They were white men with old-fashioned notions of things, and when they looked at her standing there by my side, I—I—why, I felt ashamed.

"You know what I mean. She was clean and sweet and modest, and yet the way they looked at her made me feel as if they had discovered me in the act of committing some crime. Every time that lawyer tacked the title to my name, it made me squirm. It seemed to me as if the beggar was saying it as often as he could, to make me feel that I had committed some crime against my name and race. The fawning devil told me that I was a Hulbertson with a genealogical tree that ran back to the Crusaders. He told me that a Hulbertson had once been chancellor of England, that another had been Bishop of London, and that another—oh, what's the use of telling you this sort of stuff? But I was a Hulbertson, and he had found me living with a native woman—a native woman half clothed and unable to speak fifty words of English. He made me hate him every time he turned his cunning little eyes on me!

"I told them to go back to the yacht and send a boat for me an hour later. I didn't want them to see a native woman fling her arms around me in an effort to hold me. Neena couldn't understand what they said, even if she could have heard it, but she felt it. Yes, she felt it! When that sleek family solicitor took off his cap and bowed before me, her grip tightened on my arm. Fear came into her eyes, and she edged up closer to me, as if afraid that they were going to run off with me there and then.

"It was strange what Neena gathered up out of their conversation. Afterward I discovered that in some way she got the whole purport of it, although she did not hear one word of what they said. Months afterward I found that out. She knew that the yacht was mine. She knew that something had happened in my own country—something which, as she told me, had made me a chief there. Her eyes gathered up a thousand little things. She saw the obsequious manner of the solicitor, that confounded greasy, please-don't-kick-me look of the man who wishes to ingratiate himself with his new employer.

"Neena stood beside me and watched the two as they went down the path to the boat. She did not speak, but her big eyes were wide with terror. I didn't explain till they were pulling out toward the reef. Then I told her. I said that I was going away, going to England. I told her that they were coming back from the yacht in an hour, and I told her the reason why I had sent them away. I was brutal, because that home longing made me brutal. It welled up within me and made me a devil, a selfish devil. I told Neena that I didn't want them to see a brown woman clinging to me, and that I would get the performance over before they returned.

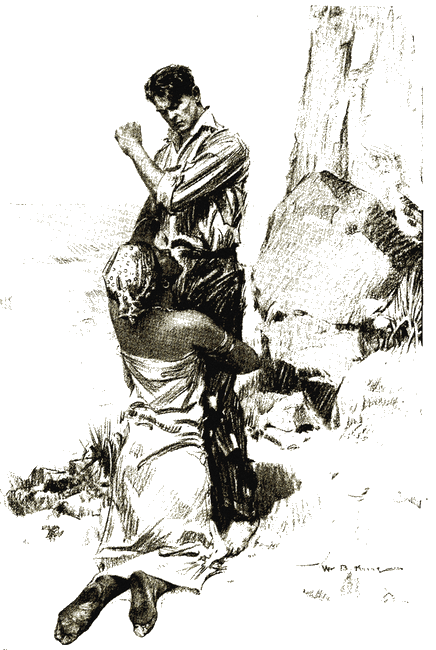

"Neena started to cry. She loved me. She worshiped me. She flung herself at me and clasped her arms around my neck. She fell upon her knees and clutched at me. In my longing to get away I struck at her in an effort to break her grip."

"She fell upon her knees and clutched at me. In my longing

to get away I struck at her in an effort to break her grip."

"I was mad, mad, mad! The words of that fawning solicitor had brought me visions, visions that tore the heart out of me. I think I kicked her. Yes, I'm sure I did. What do you think of that? I, a Hulbertson, kicked a woman who had been a slave to me for months! I was her god, and yet I didn't stop to realize her agony.

"The boat was just putting away from the yacht to pull back to the point when I tore myself away from her and made a rush for the path that leads down the face of the cliff. She wouldn't let me go. She ran after me, flung her arms around me, and held me in a grip that I couldn't break. I couldn't tear myself from her clutch. She had a strangle hold upon me.

"It was then that I lost my head completely. I struck at her fiercely. I showered blows upon her. I knocked her unconscious, and I left her there where she fell, on the edge of the cliff where the path leads down to the beach.

"I had gone down that track scores of times without ever thinking of a fall, but the story that the lawyer told and the parting with Neena had shaken my nerves to pieces, so that I lost control of my limbs. I was drunk with emotion, drunk with a home longing. A thousand, a million memories sprang on me. I sniffed perfumes that I had not sniffed for years—the gorse, the sweet smell of the downs, the odor of the flower-market at Covent Garden on a spring morning. They sprang at me, those smells! I heard noises, noises that I had forgotten. Running down that track, I heard the rattle of the buses rolling along the Strand, the whir of the hansom cabs, and the newsboys crying out 'Pyper, sir, pyper!' I heard them! You can think me mad, but every sound connected with London, every sound connected with the old days, came to me then, and the odors—Oh, they made me crazy! Why, I thought I heard the laughter of the well-dressed women along Bond Street, and it brought me a physical revulsion against Neena.

"I reeled. I stumbled. Twice I fell upon my face, clawed myself up, and ran on. I had no control over my legs, because my brain, my mad brain, was filled with memories and odors that had rushed into it from somewhere in the past. I reached the corner of the track, the corner where one has to lean back against the wall of the cliff to get by, and then—then the drunkenness that was upon me got its chance. I tried to get around the curve, tried by clinging to the face of the cliff. London was calling—my London! I was crying out to the dream Piccadilly that I was coming back, coming back again as Sir Hugh Hulbertson of Hulbertson Hall. What a maniac a man can become! I tried to cling to the cliff, but my legs, my drunken legs, gave way beneath me. I slipped, clutched at the rock, and, shrieking like a fiend, I went over the edge of the path, down, down, to the coral rocks below!

"I lost consciousness when I struck the rocks, but after a while—an hour, perhaps—I came to my senses. I tried to move my limbs, and then I found that the fall had put me out of commission. I had broken both of my legs."

IN the little silence that followed, O'Neill thought of the shambling manner in which Hulbertson of Yaon walked. He understood now.

"I lay on the rocks, trying to think," continued Hulbertson. "I had told the lawyer and the captain of the yacht to wait for me on the strip of beach below the point, and they could not see me among the rocks. I was hidden by the big boulders, so that unless any one looked down from the spot whence I had fallen, they could not get a glimpse of me.

"I had some ugly moments just then. You can imagine the kind of reflections that came to me. A Nemesis had followed me down the path, and when it had got me to that corner it had struck at me. All the sweet odors and sounds had fled. They had been swept away by that fall. I was sane. My brain was cool again, and I realized what an infernal fool I had been.

"I fell near the edge of the pool, a black pool that went in under the cliff. You have seen it, O'Neill. The natives tell stories about it. They say that in that pool lives an evil spirit. Curiously, I thought of all the stories regarding the pool as I lay on the edge of it, helpless. Those yarns came up in me, the spook yarns that I had heard told in the little huts. Lying there on my side, I stared at it—stared as if I sensed something evil about it. I could see nothing, but yet, as I lay there helpless, that pool made me creep with the horror that I sensed. There was nothing in sight, mind you, but—but the look of it gave me a feeling of goose-flesh. I thought that its black waters concealed something, something loathsome, something the thought of which filled me with horror.

"And that horror was there. As I watched the water, something came up out of it, something which chilled me—chilled me more than anything I had ever seen before. Do you know what it was? It was the feeler of a devil-fish, a blind, waving tentacle that came up out of the water about twenty feet from where I was lying and laid itself upon a slimy rock.

"What do you think I did then? What do you think I, a Hulbertson, with the blood of the Crusaders in my veins, did at that moment? Tell me, O'Neill, what you think I did?"

"Heaven knows," said O'Neill.

"I screamed!" cried the beach-comber. "I screamed out to her, to Neena, forgetting in my fear that she could not hear, even if she had recovered consciousness. I was a coward, a damnable coward! The thing frightened me, terrified me, made me feel the greatest craven the world ever saw.

"Another feeler came up out of the water, then another. It seemed as if that thing in the black pool heard me as I screamed to Neena. It did hear me! Up out of the water came its eyes—vicious eyes which looked across the dark pool toward the spot where I was lying.

"I screamed and screamed. One of the feelers was lifted up, and it waved at me as if it was pointing me out—me, with my broken legs, carrion that the fates had tossed down on the edge of the pool! In my terror I had a conviction that the fawning lawyer had been sent by the fates to tell that story, so that the devil-fish could get a meal. Don't you see? I had mad thoughts, insane thoughts! I had a belief that the three between me and the title had died, that the lawyer had wandered across the world, and that I had gone mad, just because that thing in the black pool was hungry. That's what I thought; and the terror that was upon me made me scream out like a frightened child.

"Then I saw Neena. I caught a glimpse of her on the top of the cliff, far above me, silhouetted against the sky. She was running up and down on the very edge, her head thrust forward, trying to discover what had become of me. She could see the lawyer and the captain waiting down below the point, but she could not see what had happened to me. And then again I screamed out to her, screamed out like the madman that I was!

"I don't know how to explain everything, but that pool, the mystery connected with it, and the state of mind I was in at that moment so impressed that loathsome thing upon me that I saw it in my sleep for weeks, for months afterward. Yes! I saw it, saw its slimy feelers coming toward me, toward Sir Hugh Hulbertson, before whom a cringing lawyer had bowed down. The title was worth a lot to me at that moment, wasn't it? The town house was worth a lot, and so was the place in the Midlands, with its hunting and shooting, of which that sleek, hand-rubbing lawyer had spoken!

"Don't you understand the kind of thoughts that came into my mind? The handful of gifts that fortune had flung to me an hour before could not stop the big feelers that were coming toward me, slowly, haltingly, but surely. The awful thing that stopped every now and then and watched me didn't know that I was Sir Hugh Hulbertson, and that I had the blood of Crusaders in my veins. It saw in me carrion—carrion! Those rows of suckers along the big feelers were waiting to get at the blue blood that the sniveling beast of a lawyer had spoken of!

"I can shut my eyes and see that hideous thing now. It burned itself into my brain so that I shall never forget—never! I tried by clawing the rocks to drag myself along, but I got wedged, and then the pain from my broken legs and the mental agony I was suffering were too much for me, and I lost consciousness."

THE beach-comber halted. Lawrence choked back a little exclamation. The soft voice of the native woman crooning a tribal song came from the shack behind. Hulbertson was looking out beyond the reef, where the jagged teeth of coral bit at the big waves that were rolling toward the white beach.

The beach-comber's voice was lowered when he took up his narrative.

"I came to my senses to find some one dragging me, dragging me over the coral rocks. Yes, it was Neena. I don't know how she found me, but she did. She found me lying there on the edge of the pool with that cursed thing crawling toward me. She dragged me to the bottom of the path, and then—I'm hanged if I know how she did it—she got me on her back and carried me right up the path to the hut.

"She laid me on the bed, set my legs, put them in splints, and then gave me a drink of jalu leaves that eased the pain I was suffering. Neena had quite a reputation as a doctor, and she fussed round me as if she was glad that I had given her an opportunity to show her skill.

"The family solicitor and the captain of the yacht came up the track after Neena had got me fixed up. They had grown tired of waiting, and had come up to see what was wrong. I made Neena pull a bamboo screen in front of the bed, and I talked to them from behind the screen. At least, I talked to the solicitor. I dictated a little statement, which I made him write out and hand in for me to sign; and after I had signed that statement I told him he could take himself and the yacht back to a young cousin whom I had mentioned in the statement, and who was then trying to burn up London on two hundred pounds a year. He married a Gaiety actress six months after he got the title, and he's been doing sensational stunts ever since."

The silence seemed to come down heavier upon the island as the beach-comber stopped speaking. The cooing of a disturbed wood-dove came from the palm grove; the woman still sang gaily within the shack.

The song seemed to draw Hulbertson. He got to his feet and turned toward the little coral-limed dwelling. It was then that Baxter asked a question.

"Was there a doctor aboard the yacht?" he asked.

"Yes," said Hulbertson.

"Then why didn't you let him attend to your legs?"

"Like thunder!" snorted the beach-comber. "Do you think I'd hurt her feelings by letting the ship's sawbones touch me after she had fixed me up? Not I!"

He turned and walked up the path toward the shack, the curious, disjointed movements of his legs being plainly visible to the three men on the sands as his big frame showed against the soft glow that came from the doorway.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.