RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a Dutch-Javanese poster (1914)

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

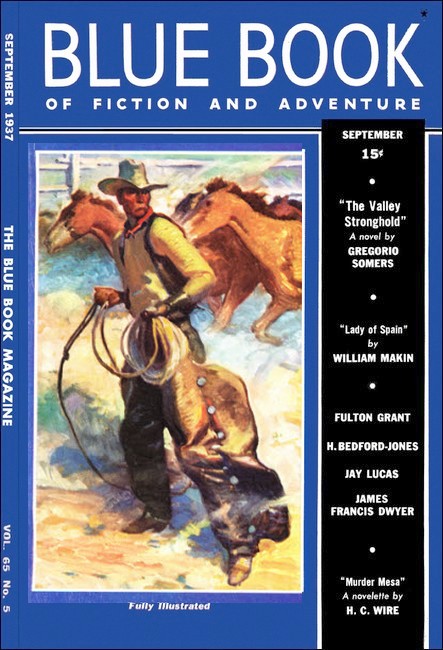

RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a Dutch-Javanese poster (1914)

Blue Book, September 1937, with "The Wild Girl

James Francis Dwyer

JAMES FRANCIS DWYER (1874-1952) was an Australian writer. Born in Camden Park, New South Wales, Dwyer worked as a postal assistant until he was convicted in a scheme to make fraudulent postal orders and sentenced to seven years imprisonment in 1899. In prison, Dwyer began writing, and with the help of another inmate and a prison guard, had his work published in The Bulletin. After completing his sentence, he relocated to London and then New York, where he established a successful career as a writer of short stories and novels. Dwyer later moved to France, where he wrote his autobiography, Leg-Irons on Wings, in 1949. Dwyer wrote over 1,000 short stories during his career, and was the first Australian-born person to become a millionaire from writing. —Wikipedia

JAN KROMHOUT, sitting on the veranda of his jungle hut, watched a silver gibbon or wou-wou climb along the limb of a tapan tree. There was a soft smile on the face of the big Dutch naturalist. The ape, to judge by his movements, was very old, and he climbed carefully. He reached a fork and seated himself, then with his long fingers he combed his beard and chased several small insects in the fur on his stomach. "He is waiting for his wife," said Kromhout.

"Looks rather tottery," I commented.

"Ja, he is very old," said Kromhout. "He is one of the oldest of the Hylobates leuciscus that I have ever seen. Last year I thought he would die. He was so sick that he let me carry him in here and feed him. He thought he was dying, too. He did so. He looked at me as much as to say: 'What are you nursing me for? I am through with this jungle life. I am going somewhere else.'"

The gibbon from his high position looked clown on the naturalist and made a grimace. He coursed another flea along a nip circuit, made a kill; then leaning back, he closed his eyes and dozed.

Jan Kromhout spoke.

"Did you ever hear of the steamer Soerakarta?" he asked.

"The Soerakarta?" I cried. "Why—why, of course!"

The mention of the steamer brought to my mind all the stories I had ever heard of that nearly legendary vessel—the S.S. Soerakarta that during the latter months of her life never charged a passenger for a voyage! The dream ship that waddled up and down the hot seas of the Malay, filled with guests who ate and drank of the best without paying a single guilder to the owner! Visiting little lost ports, debarking those who were tired of the owner's hospitality, taking aboard new voyagers whose only qualification was good-fellowship.

Jan Kromhout took a drink of schnapps, smiled over the excited manner in which I had answered his question, then stirred me again with a short statement. "I was a passenger on the Soerakarta," he said quietly. "I mean that I was a guest of General Van Shoorn. For five months I was on that steamer."

Now, if a man whom I knew to be absolutely truthful had calmly informed me that he had sailed out of Palos Harbor with Christopher Columbus on board the Santa Maria, the effect upon me would have been similar to that produced by Kromhout's statement. I had heard many extraordinary stories of the Soerakarta, but I had never met a man who had sailed on her with the millionaire General Van Shoorn. Old men, sitting on rotten wharves in ports from which the god of trade had fled, had told me that they had seen her during those golden days of free cruising. They would gabble of the strange passengers that came ashore from her—carousing devils from all ports of Malaysia. How some, tired of the vessel, stayed; and how others, hearing of the fine food and drink aboard the steamer, took their places.

"You never told me!" I cried, swinging upon Kromhout.

"You never asked me," he said gently. "I have never told you the Christian name of my father, or the breed of the little dog I played with on Nieuwe Kerk Straat in Amsterdam when I was a boy. I would have told you if you had asked."

"But—but the Soerakarta!" I shouted. "Why—why, she was the ship of romance! She was something that poets would sing of! She was a million dreams turned into wood and iron! She had the pennant of poesy on her foremast!"

The big Dutchman considered my excited remarks in silence. He glanced at the old gibbon on the limb of the tapan tree.

"It is funny to think of the silly things that are stored up in the memory of fools," he said bitingly. "Always I have been puzzled. The world is so hungry for trash. Bits of colored rag and tinsel. Ja. The red and yellow petticoats of a gypsy will get the eye when she is walking close to an honest Vrouw in fine homespun. Poesy? What the devil is poesy but bits of colored nonsense! There have been great Dutchmen in Java and Sumatra, men like Daendels and Pieter van den Broeck; but they have been forgotten, while the name of General Van Shoorn stays in the brains of thousands because he owned the Soerakarta and pulled a lot of fools around the Malay and charged them nothing."

I ACCEPTED the slap without showing annoyance. I wanted to hear Kromhout's story of his voyage on the Soerakarta, and it would have been inadvisable to argue with him.

"I knew General Van Shoorn before he owned the ship that he named after his home town," began Kromhout finally. "Do you know the town of Soerakarta? Nee? It is just six hundred kilometers from Batavia, and it is a nice place. The natives call it Solo, and right there is the palace of the Soesoehunan. The Dutch have given him a little zoo to play with, and they have taught him to say 'yes' or 'no' when they want him to say 'yes' or 'no.' The Dutch are as good as the English in teaching colored rulers how to speak up quick. Ja, they are.

"General Van Shoorn had twenty million guilders, and a bad heart—very bad! I was in Batavia when he came down to see a big specialist. That specialist listened to Van Shoorn's heart like you would listen to the ticking of a cheap watch. For five, ten, fifteen minutes he listened; then he straightened himself up and said: 'In six months you will be flying.'

"'Flying where?' asked the General, pulling on his shirt.

"'I don't know,' said that specialist. 'P'raps to the Milky Way, p'raps to that red star that they call Betelgeuse. There must be plenty of places to fly to up there! My fee is three hundred gulden.'

"General Van Shoorn was sixty years of age. He had never married, and all his blood relations were dead. He went out of that doctor's office in Molinvliet-West, and he took a carriage down to Tandjong Priok, the port of Batavia. He was thinking what he would do with those six months. It is not much time, six months.

"He sat down at Tandjong Priok and stared at the big ships. Some of them were filling their bellies with rubber and coffee and pepper and rattan and sugar and tin; and others were spewing out stuff that they had brought from America and Europe. And there was one steamer that was lying in the outer harbor, and she looked deserted.

"Van Shoorn asked a sailor about her. He was told that the firm in Amsterdam that owned her had gone bankrupt. They could not pay her port dues, and her captain and crew had left her because they had got no wages. There were only two watchmen on board her.

"There was a nice breeze coming in from the Java Sea. It carried all the fine perfumes of the Malay—the hot spicy perfumes that stir the blood. They rolled in from the Karimata Strait, from the Anambas and Tambelan Islands, and they whispered to General Van Shoorn. They told him of little lost ports where the casuarina trees make soft music, where mystery has not been crushed by the big feet of western men, where there are still primitive graces that were ours in the days when the world was young.

"I know how they spoke to Van Shoorn, because I met him next day in the Deutscher Turnverein, and he told me. I thought he had gone mad. He had bought that boat by cable. He had given orders to chandlers and outfitters to get her ready with all possible speed. He had changed her name to Soerakarta, and was rushing around Batavia inviting every friend of his to go on a cruise.

"'You will come, Kromhout?' he said.

"'Where?' I asked.

"'Anywhere!' he cried. 'Up and down the Malay. I have six months to live! I have twenty million guilders—I am going to enjoy myself!'

"He had a sheet of paper in his hand, and he wrote my name on it before I could say anything. 'That makes twenty-eight,' he said. 'She has sixty cabins. If you know of any good fellows, give them an invitation. We will sail as soon as she is ready.'"

JAN KROMHOUT paused, looked up at the old monkey and lifted his glass. I had a belief that the gibbon bowed his head in courtly salute. Quite a fellow, was the ape; there was a man-of-the-world air about him.

"I met General Van Shoorn three days later at the Handelsbank," continued Kromhout. "I told him that I did not think I could go. 'But you must, Kromhout!' he cried. 'I have a great idea. When we are ready to start, every one of my guests will write down the name of a port he would like to go to. We will put them in a hat, and get the barman at the Hôtel des Indes to draw one out. We will go straight to that port. When we are tired of it, we will have another drawing. Of course, they must be ports of the Malay.'

"'It is silly,' I said to him. "'Of course it is silly!' he snapped. 'But this is the first time I have had a chance to do something silly. I have been too busy making money, and now I find that I have but six months to live. Why can't I be silly? Are you coming?'

"'I am not,' I said; and I left him as he ran after the big fat Dutch manager of the Nederlandsche Handel-Maatschappij to give him an invitation.

"Three nights later I was in the bar of the Hôtel des Indes. Van Shoorn was there with thirty-seven men who had accepted his offer of a free trip. Each one of those men put down on a bit of paper the name of a port in the Malay. They put the names in Van Shoorn's topee, and the barman drew one out.

"It was funny. For days and months I had been hoping that I could go to Amboyna. I do not know why; it was just one of those things that get into one's head. Ja, it was Amboyna that the barman pulled out of the hat. Next morning I packed my bag and went on board the Soerakarta. There were forty of us as we pulled out of Tandjong Priok. We sang 'Wien Neêrlandsch' at the top of our lungs. There was much champagne drunk. Much."

Possibly the memories of that morning made Kromhout reach again for his glass of schnapps. As he lifted the glass, the old ape in the tree lifted his paw in salute. The ape had made a keen study of the Dutchman's movements.

"They were good fellows, those boys on the Soerakarta," continued Kromhout. "They ate and they drank and they sang and they played cards, and they had not a care in the world. It is nice to forget life. We Dutch have a proverb, 'De tijd hebben God en wij'—Time is God's and ours.' It was so on the Soerakarta as we rolled down the Java Sea. Ja, ja. Some of them were married, but they forgot their wives. Some of them had big business affairs, but they pushed them out of their heads. They lay in the sunshine and forgot their names, and I think that is something like a prayer. If the good Lord looked down on that steamer, I bet He would have smiled.

"We came to Amboyna, and I said good-by to all those men, thinking that I was going to stay there. But Amboyna did not taste quite right to me after that trip. It is not much, Amboyna. It was not the place that I had dreamed it would be. There is too much dark blood in the Dutch of Amboyna. It is the bad thing of the Orient. There are folk there that have a drop of all the bloods of the East in their veins, but they think they are Dutch!

"WELL, in two days I was sick of that place. I heard the siren of the Soerakarta, and I ran down and caught the last boat for the steamer. When we all got on board, each of us wrote another little scrap of paper, and the barkeeper pulled one out of Van Shoorn's topee. Van Shoorn called out the name to the sailing-master. It was Makassar. I did not care. I was beginning to like that steamer. I was sorry for General Van Shoorn. In his cabin he had a calendar with the six months marked off in red ink, but he was never sad. Myself, I do not go near those doctors. They think it funny to say to a man, 'in three months you will be dead.' In Amsterdam there was a man named Peter Kruithof. One of those funny doctors made an examination of Peter and told him he would be dead in a month. Peter Kruithof killed him and was hanged. The medical papers did not say anything about it. They thought lots of patients might do what Peter did.

"We went to Bali, and from there to Bandjermassin. Then we went across the Celebes Sea to Sandakan, still pulling bits of paper out of Van Shoorn's hat!

"The people of the ports heard about that plan, the harbor-masters and the pilots; and they thought we were all mad. They would stare at the captain when he said he did not know what port he was going to till we had made the drawing. The Soerakarta became famous. They told tales about us at Bangkok and Penang, at Zamboanga and Port Moresby. And we waddled here and there, eating and drinking and collecting souvenirs.

"That steamer was loaded with souvenirs—with brass gongs and knives, and bits of silver-work and bird-of-paradise feathers, and batik calico and sarongs. And there were seventy-four different kinds of parrots, and so many monkeys that no one bothered when half a dozen or so of them got sick of the steamer and went ashore at a port.

"It was after we left Sandakan that I made friends with Hugo Sonsbeeck. He was a young man who had been on board the Soerakarta from the time we left Tandjong Priok, but I had not spoken to him. That night after we left Sandakan, I found him sitting by himself. He was nearly drunk, and he was crying like a baby.

"I asked him what was wrong, and after a long time, he told me. Each time there had been a vote as to where that steamer should go, he had written down the name of a tiny island in the Paternoster Group—a little speck of ground that had fallen from the shovel of the Almighty when He was building Asia. It was called Upeil. Seven times that youngster had written it down, but the barman had never drawn it.

"'Why do you wish to go there?' I asked.

"'I have a reason,' he snapped.

"'Ja, you have a reason,' I said; 'but if you tell me the reason I might help you.'

"After a long while that young fellow told me. One day on the Koningsplein at Batavia he had given a few cents to a sailor, and that sailor had told him a story about Upeil. He had said that there was a white girl living there. She had been washed up there from a wreck years before, and she had grown up by herself, living on fish and fruit and small animals. This sailor had seen her when his ship lay off the island. She had come to the top of a cliff and peered down at them, but when they put out a boat, she had fled into the palm trees.

"The story had got into that young man's head. He wanted to go to Upeil.

"I was sorry for him. Very quietly I told some of my friends on board the Soerakarta some of them who did not care where they went to. We decided to play a trick on Van Shoorn. At the next drawing nine of us wrote Upeil on our voting papers, and the barman pulled one of those papers from the hat.

"'Upeil?' cried old Van Shoorn. 'Where the devil is Upeil?'

"He sent for the navigating officer, and they found it on the chart. There was no harbor. There were coral reefs inshore. A ship would have to lay out two or three miles and send a boat in through the passage in the reefs.

"Van Shoorn hesitated. Then he said: 'All right! We made a rule, and we'll stick to it. We're going to Upeil.'"

Kromhout paused to moisten his lips. The gibbon on the tapan limb opened his eyes when he sensed the interruption in the narrative, and once again he lifted his right paw as the naturalist drank.

"We picked up that island one morning when the Java Sea was filled with all the fine odors of the Malay. Ja, it was a beautiful morning. And all the men on the Soerakarta were laughing and joking because they knew then why that young fellow wanted to go to Upeil. They had heard the story, and they were all on deck with glasses, watching for that girl who lived there. They did not believe it, of course. They thought it a great joke that a drunken sailor had told in return for the price of a meal.

THE Soerakarta stood about two miles offshore; and eight of us, with Van Shoorn, went off in one of the boats. The young fellow was with us. He was much excited, and now and then he got mad with the others who were poking fun at him.

"'There she is!' one of those fellows would yell; and when he swung round to look, they would laugh themselves sick.

"That passage was difficult. There were coral-mushrooms that were just a few inches under water, so that you did not see them till the boat was right on top of them. They were bad. They would come up out of thirty fathoms of water, and they were big enough to tear the side out of a ship. Van Shoorn thought if there was a girl on that island, the ship that had brought her there had struck one of those mushrooms.

"We made a landing in a little cove. The cliffs ran up straight above our heads. We climbed out of the boat onto a beach of pounded coral, and we stood around with silly grins on our faces. Just for a few minutes we stood there; then I caught sight of that young fellow's face.

"He was staring upward at the top of the cliff. Ja! And his face was not the face he had three minutes before. It was plastered with astonishment, with wonder, with joy. And he was gurgling like an ape with a bone in its throat.

"She was there! Ja, the girl! Standing on the very top of the cliff, looking down at us. Outlined against the sky!

"I have never seen anything prettier than that girl as she stood on that cliff. Never! She had nothing on her but a scrap of cloth around her loins, but she was dressed in her own innocence. Do you know what I mean? She made us who were staring at her feel like damned fools that had blundered into a place we had no right to enter.

"She did not move, and we did not move. Like a statue she stood there. Ja, like a golden statue. And we, with our heads up like startled giraffes, stared at her, feeling ashamed at what we were doing, but not able to pull our silly faces away.

"Van Shoorn was the first to come to his senses. He walked to the boat and took out the lunch that we had brought with us. He spread it on the beach, the sandwiches and the coffee, and he made motions with his arms that it was hers if she wished it.

"'Get back in the boat and give her a chance!' he snapped, and we hopped back into the boat like naughty boys who had been caught peeping through the window of a girls' school.

"'Pull away!' said Van Shoorn. 'We'll frighten her if we stay here!'

"That young fellow Hugo Sonsbeeck made as if he would leap back on the beach, but Van Shoorn grabbed him by the collar. 'You stay where you are!' he snapped. 'Leave this business to me!'

"'But I first heard of her!' whined the young man. 'She—she is mine!'

"'Like hell she is!' said Van Shoorn.

"That young Sonsbeeck was fighting-mad, but Van Shoorn was in a temper.

WE pulled back to the Soerakarta, and that steamer had a list on her because every man on her was at the rail with glasses watching the shore. They had seen the girl, from the ship.

"For more than an hour we watched her standing on the top of the cliff; then she started to climb down to the beach. She walked around those sandwiches as if she thought them a trap. Ja, like a nice animal she circled them, till at last she was sure that there was no danger and squatted down beside them.

"Those men on the steamer would not go down to the saloon for lunch. They would not leave the rail. They had food served to them there, and they jabbered like a lot of old women. Van Shoorn had much trouble with them. Now and then a bunch of them would say, 'Let's go ashore and talk to her!' and Van Shoorn had to stop them from stealing the boats.

"After lunch there was a great argument. Van Shoorn decided to take that girl some clothes, and every man on that steamer ran to get the sarongs and the shawls that he had bought for a wife or sweetheart back in Batavia.

"They piled them on the deck, and Van Shoorn swore at them. He was getting mad. Much mad. Ja! That young fool Hugo Sonsbeeck had his arms full of batik underwear that he had bought for his sister, and he wanted to carry the whole lot of it ashore to the girl.

"'Your stuff is not going, and you are not going!' shouted Van Shoorn; but at that, the boy cried so hard that a lot of us asked Van Shoorn to let him go.

"We took the clothes and some more food to the beach. The girl had seen us coming, and she had raced up to the top of the cliff. She watched us as we laid the presents on the sand. Van Shoorn had not brought any of that souvenir stuff—sarongs and silk underwear; but he had brought his overcoat, on the chance that the girl might like it. The others grinned as he laid it on the sand beside the fluffy stuff. Ja, they grinned a lot. It was old, that overcoat, old like Van Shoorn himself. Old and friendly.

"When we had spread out the stuff, we pulled out to sea for about half a mile and waited. The girl came slowly down the cliff path, her eyes on the clothes and the food. On tiptoes she came toward the pile of petticoats, circled them and sniffed at them. She picked up one piece after the other. Nice pieces: Javanese slendangs made of beautiful cloth; pandjangs to wrap around her waist, all covered with patterns in gold thread; and little caps of silk with silver tassels. They were very generous, those fellows!"

We pulled out and waited. The girl came slowly

down the path, her eyes on the clothes and food.

"We watched her from the boat. Five times she went round that spread of nice clothing; then she did something that made us laugh. She picked up that old coat of Van Shoorn's, turned it round and round as if she were trying to get the hang of it; then she put it on inside out and walked up the track to the top of the cliff. Now and then she stopped and listened to the laughter that came from the boat."

KROMHOUT paused and looked up at the old gibbon. The monkey sat up expectantly. With the air of a boulevardier, he stroked his whiskers, straightened his shoulders and gave a pat to the ruffled hair on his stomach.

"His wife is coming," whispered Kromhout.

From the leafy branches above the old ape dropped a graceful lady of his own breed, a lithe, alert female who moved with the speed and grace which characterize the gibbon, a speed which makes it possible for them to leap at small birds and capture them on the wing.

The lady gibbon reached the old chap. She was playful. She patted him on the nose with her long paw; and when he protested mildly, she gave him a dig in the ribs that brought a grunt that seemed to delight her. She danced around him, swung by two fingers from a bough above his head, then startled him by turning a complete somersault in midair and catching a limb as she was dropping toward the ground.

Jan Kromhout's broad face showed his pleasure. "She does that every day," he whispered. "It tickles him. She is very nice. I think he is pleased that I nursed him back to life when he thought he was going to die. Ja, I think he is pleased. That is why he lifts his paw when he sees me taking a drink of schnapps."

MY eagerness to hear the finish of the story of the wild girl made me interrupt the naturalist's contemplation of the gibbons. "Did they coax her aboard the Soerakarta?" I asked.

"Ja, they did," answered Kromhout. "It took five days to make that girl believe that no one wished to hurt her. They filled the beach with all sorts of things, trying to please her. I was a little tired of that business. On the third day I said it might be better to leave her there as she seemed to be happy, and that young fool Hugo Sonsbeeck tried to hit me. He did not sleep during those five days. He stayed on deck all night with a lamp, making signals to the shore. He made me sick with his goings-on.

"When we got that girl on board, we were all tired. Van Shoorn held a drawing to see where we would go, and the barman pulled out a piece of paper with Batavia on it.... I will tell you something: Every bit of paper in Van Shoorn's hat had Batavia on it! Ja, Van Shoorn's too."

"And the girl?" I asked. "Did she marry this young Hugo Sonsbeeck?"

"Nee!" snapped Kromhout. "She married old Van Shoorn. That specialist who said he would die in six months was a fool. That was seventeen years ago, but he is still alive. That girl lives with him on his big estate at Soerakarta. She is very clever with animals. She can imitate the cries of all the birds and apes of the Malay. Once when I was standing in front of the Hotel Sleir at Soerakarta, she hissed like a cobra in my ear. I hopped so quick that I fell and sprained my ankle. I was very mad with her, but she only laughed at me."

Jan Kromhout lifted his glass and looked upward at the old gibbon on the limb. But the gibbon did not respond. He was asleep, his beautiful young wife cuddled in his long arms.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.