RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

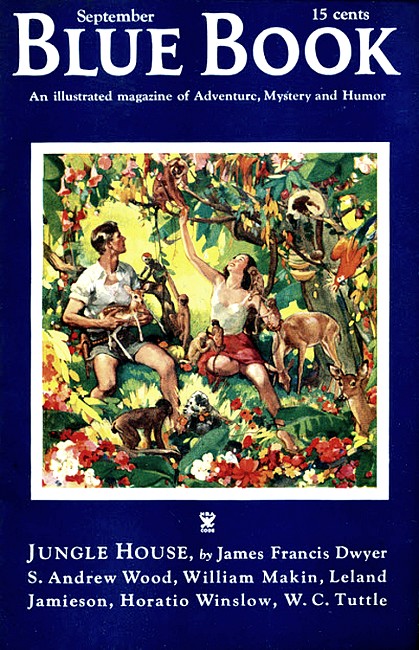

Blue Book, September 1934, with "Jungle House"

James Francis Dwyer

JAMES FRANCIS DWYER (1874-1952) was an Australian writer. Born in Camden Park, New South Wales, Dwyer worked as a postal assistant until he was convicted in a scheme to make fraudulent postal orders and sentenced to seven years imprisonment in 1899. In prison, Dwyer began writing, and with the help of another inmate and a prison guard, had his work published in The Bulletin. After completing his sentence, he relocated to London and then New York, where he established a successful career as a writer of short stories and novels. Dwyer later moved to France, where he wrote his autobiography, Leg-Irons on Wings, in 1949. Dwyer wrote over 1,000 short stories during his career, and was the first Australian-born person to become a millionaire from writing. —Wikipedia

THE bulky Dutch naturalist Jan Kromhout was busy. A maroon-red monkey, a fine specimen of the Bornean sacred hanuman (Semnopithecus hosei) had injured his ear in a combat with a husky waw-waw. The stubby fingers of the Dutchman deftly bandaged the torn auricle; and as he worked, he talked.

"The ear is a wonderful thing," he said. "You can find out more from the ear than you can from any other organ. Ja. It has a lot to tell. Did you know that in all the anthropoids, it is only the gorilla that has the rudimentary lobule? Apes, baboons and little monkeys have ears that are nicely shaped; but it is only the gorilla that boasts a lobe. It is small, but it is there.

"Do you know why? Because the gorilla is the nearest to man, and because he has great strength and intelligence. If you have no lobes to your ears, you are not—ja, ja! I knew you would feel your ear! Your lobes are not great. Just medium; but you can console yourself when you look at persons who have none."

The small hanuman, so different in color from his slate-tinted Himalayan relatives, protested against the tightness of the bandage, and Kromhout cuffed him amiably.

"It is the strong nations that have the biggest lobes to their ears," continued the naturalist. "The Americans, English, Germans, Dutch, and the Norse folk. That is why I do not believe in the rise of the Japanese. There is not one big lobe in twenty of them. Nee! And without lobes to their ears, a nation is nothing."

The maroon-red monkey raised a little paw and felt the bandage with his sensitive fingers. He looked inquiringly at Kromhout, as if he wished to know how many days he would be forced to wear the linen fillet around his head.

"You will be all right in a week," growled the naturalist. "You must not fight with that big waw-waw. He is too strong for you. Now go back to your cage."

The little hanuman whimpered softly, slipped from the stool and hopped back into his cage. He made a face at the belligerent waw-waw who had inflicted the damage, and the waw-waw grimaced in return.

"Of course, if the monkeys had lobes to their ears, they might have got somewhere," said Kromhout slowly. "The Shans on the Mekong River believe that at one time the monkeys could read. Often you will see an ape holding a big leaf in his paws the way a child would hold a piece of paper, staring at it as if he saw something written there. The Shans think they have forgotten how to read. I do not know. Perhaps the monkeys that did the writing did not make nice stories for them. We might forget how to read, if all the stories that were written were foolish tales....

"Of course they can talk! They can talk well. Once, years ago, I heard a mias, the Simla satyrus, or orang, tell a story to an old native who had been brought a hundred miles to find out what the mias and the other apes were saying. The native was a hundred years old, and could talk the monkey language. It surprises you? Ja! It surprised me. But I heard it with my own ears.

"YOU would like to hear it? Perhaps I you will not believe,

but it is true. Belief is the greatest of the virtues; and in the

Orient you must have it or you are a fool.

"This thing that I tell of happened at Soerakarta, that is also called Solo. It is, as you might know, about six hundred kilometers from Batavia, and there is the Palace of the Soesoehunan, who gets a big salary from the Dutch Government for just sitting quiet and taking no notice of how the Dutch Resident runs the country. There are lots of native princes in the East, getting big money for shutting their eyes. The English and the Dutch have shown them that it is the easiest way out of trouble.

"At Solo there was a Portuguese named Josť Basto. One day he did not have five guilders, and the next day he had a million. No one knew how he had got the money. People whispered to each other, but they did not ask Basto. He was a bad fellow, was that Portuguese. He could use a knife quicker than any other man I have ever seen; so no one said: 'Hey, Senor Basto, how did you get your money?' Not much!

"The Soesoehunan has a big menagerie at Solo—panthers and crocodiles and monkeys and all kinds of snakes. So Josť Basto with his million gulden wanted a menagerie. He wanted to be bigger than anyone else.

"I sold him many monkeys. A big mias, some macaques, ring-tailed lemurs and two gibbons. The gibbons were siamangs, with the index and middle fingers joined by a web, and the pair I sold that fellow Basto were very pretty. They were husband and wife, and they were a pale fawn-color, with a white stripe across the forehead.

"They loved each other a lot. They would sit for hours with their long arms around each others' necks as if they were afraid of the world; and when the Portuguese and his wife would come to look at them, they would cry softly, making the single note which is different from that of their blood brother, the waw-waw, who has two notes. They did not like that fellow Basto; and they did not care if he knew they did not like him.

"Josť Basto had those siamangs for two years, and they had no little ones. And he wanted them to have a little one. He is not a fool, the gibbon. Not much. That pair did not wish to have a little baby that would spend its life in a cage to amuse a fat Portuguese.

"Basto spoke to me about it. I told him to put a male gibbon in the next cage so as to make the husband of the siamang jealous. Basto did that, and after a while that pair had a baby—a little male baby that was puce-colored, and who was more frightened of the world than his father and mother.

"When Basto came to look at him, the little fellow would hide behind his father and mother. All that Basto and his wife could see was a bright eye peeping at them, and that made the Portuguese mad. Very mad. His wife had a little girl who was about two years of age just then, and the wife wanted the child to see the baby monkey.

"One morning Basto sent a man into the cage to get the baby. It was a big cage, and the gibbon is the most agile ape in the world. He has no tail, but his arms are so long that he can move faster than any other primate. The natives say that a gibbon is so swift that he can catch a bird on the wing. I have never seen that, but I believe he could.

"When the man went into the cage, the mother ape grabbed the baby, while the father started to trip up the fellow that chased her. The mother bounced from one side of the cage to the other, the baby clinging to her neck, while the male gibbon was giving hard kicks and scratches to the man.

"Basto thought the servant was a fool. He swore like a crazy man, and jumped into the cage to help. He didn't like those apes fooling him. He had a million gulden, and the apes were just funny things he had bought to amuse himself.

"The father gibbon jumped on Basto's shoulders when the Portuguese climbed into the cage. He was game, was that ape! Very game. He got a grip on Basto's hair, and he pulled it till the Portuguese squealed. And he poked one of his fingers into that chap's eye. The little puce-colored baby was a treasure, and they were not going to let anyone steal it without a fight.

"Basto yelled when the ape put his finger in his eye. One of the servants handed him a stick with lead in the end of it, and when he swung himself free of the gibbon, he brought that stick down on the ape's head. The blow knocked the father gibbon unconscious; then Basto and the servant cornered the mother and snatched the little baby from her.

"Basto was mad about that ape sticking his finger in his eye. He could not see out of it. He jumped up and down in front of the cage and he swore that he would never give the baby back to the gibbons. He told the servants to take the little fellow up to the nursery where his own child was playing, and to keep it there and feed it. Never would it go back to the ape who had nearly poked Basto's eye out.

"IT is bad business to steal a baby. Very bad business. Every

morning for a week, when Basto and his wife came through the

garden, those gibbons would be waiting—clinging to the bars

of their cage, their wet noses pushed through. They would take up

that position at daylight, waiting for Basto to come by. The poor

devils thought that he would surely bring them back the little

puce-colored baby. Not a whimper would come from them. They were

quite silent, but the mother would point to her breasts as they

went by. It was very sad.

"At the end of a week those two apes did something that was curious. Very curious. Up till then they were silent. They did not make a sound. Just looked at Basto with their wet eyes, the mother ape touching her breasts. But on the eighth day as Basto came by, they barked a word at him—just one monkey-word. Barked it fiercely! And the funny thing was that the other monkeys in the cages made the same noise. Every one of them! The macaques, langurs and capuchins joined in. Every monkey in the place from the big mias down to the little ring-tailed lemurs clutched the bars of their cages and screamed that one monkey-word at Basto.

THE next morning, and the next, they did it the moment Basto

appeared in the garden. It got that fellow pretty mad. You bet!

He would not have minded much about the little monkeys jabbering

at him, but when the orang-utan started yelling at him, he lost

his temper. The orang-utan is brainy. The cranial capacity of the

ordinary human being is about fifty-five cubic inches, and that

of the orang is twenty-seven, but the orang's is mostly filled

up. His brain is very like the brain of a man, except in weight

and size. He knows a lot.

"Basto struck at the paws of the apes when they yelled at him, but that did not stop them. Not one bit! That damned chorus went on all the time he was in the garden. The same monkey-word, over and over again. It was a little like some of the college cries that you have over in the United States.

"That monkey-word got into Basto's brain so that he heard it in his sleep. He would jump out of bed and cry to his wife. 'Listen!' he would scream. 'Listen to them barking at me now!' But there were no sounds at all. The apes were all asleep, yet Basto heard their barking. He would struggle to get a rifle, and the servants had to be called to stop him from murdering every ape in the menagerie.

"I heard about the trouble, and I went to see him. I listened to those apes barking at him. It was curious. 'Why don't you give the gibbons their little one?' I asked. Basto laughed like a madman. 'I can't!" he cried. "The little wretch didn't like the food we gave him, and he went and died! But I wouldn't give him up if he were alive! I'll see those apes in hell before I let them beat me! What I want to know is the meaning of the word that they bark at me?'

"I told him about a native who lived near the big temple of Tjandi Bororboedoer, that is up beyond Djokja. The native was an old man, more than a hundred years of age, and people said he could talk with the apes that were around the temple. I had watched him myself. When the old man started to talk, all the monkeys would sit quiet and listen to him, their heads on one side; and when he finished, one or two of the oldest monkeys would reply to him.

"Basto was so crazy to know what those monkeys were calling him that he sent off quick for the old man, and in two days he was at the house. He was blind, and he was led by one of his sons, who was himself so old that he had to walk with a stick.

"That blind man was the oldest person I have ever seen. His age came out from him and frightened you. When he shuffled into the room, you were filled with queer imaginings: thoughts of Dubois and the Pithecanthropus erectus that he found here in Java; thoughts of the hairy mammoth and the big blind snakes that crawled in the slime of a world in the making. Ja! He made me cold. He was a bit of skin and some bones that linked us up with forgotten centuries. He was history on two legs.

"That blind man did not know that Basto had taken the puce-colored baby from the gibbons. No one had told him. He had come from another part of the country, and had heard no gossip.

"'Come with me,' said Basto, 'and tell me what those damned monkeys are yelling at me!'

"There were six of us. Basto, the blind man, the son of the blind man, two servants and myself. We went into the menagerie, and the moment the monkeys saw Basto, they started to bark that word. Bark it in chorus! It was deafening.

"The old blind man stopped with a grunt of astonishment. For a minute or so he listened; then he opened his mouth and cried out something to the apes—something that made them shut up with a suddenness that was startling. It seemed as if he was asking them what the devil they meant by barking that monkey-word at Basto.

"All the monkeys were looking at the old man, their noses thrust through the bars, their little eyes showing astonishment. And in the silence the old man repeated his question.

"It was the big mias, the Simla satyrus, that answered the blind man. It was right that the mias should give the reply. He is clever, you bet. He thinks, does that fellow. His brain is greatly convoluted. That simian fold in the brain that scientists call the sulcus, and which was supposed to separate the great apes from man, has now been found in the brains of Negroes in Africa, so the mias has a human brain. And he can think better than a dozen darkies.

"THE mias started to chatter to the blind man. I knew what he

was telling him. He was telling of the kidnaping of that little

puce-colored baby. The mias would nod his big head at the cage of

the gibbons, and the gibbons would nod back. And the mother

gibbon would shake her breasts, and tears would come out of her

eyes and dribble down her nose. And the old man clung to the arm

of his son and listened. And all the little monkeys listened. And

Basto stood there with his big mouth open, glaring at the mias,

knowing that the orang was telling the blind man that he, Basto,

was a swine and a hell-hound and a baby-thief. And he was,

too!

"When the mias stopped speaking, the old man turned to Basto. 'He has told me that you stole the little one of the gibbons,' he said, 'their little baby that they loved.'

"Basto didn't want to hear that. 'That's my business!' he roared. 'What is the word they bark at me? Tell me that! Quick!'

"The old man was silent for a few minutes, and his silence got Basto so mad that he stepped across and shook him. The blind man got angry. He said he could not find any word in his language that had the same meaning as the monkey-word. Not one! It seemed as if he was trying to think up some terrible word that would blast the ears of Basto. Some word as spiteful as the tongue of a snake, as green as verdigris, and as hot as lava.

"'Tell me as near as you can!' yelled Basto.

"That old blind man started to explain the meaning of that monkey-word. It meant a lot. Ja, ja! That old chap said that when one monkey used it to another monkey, it meant that the fellow it was flung at was a cross between a parricide, an illegitimate idiot, a baby-thief and a hangman's assistant.

"The old fellow was warming up as he tore the stomach out of that word and explained its inwards to Basto. He couldn't see Basto's face, he being blind. If he had seen, he might have stopped. Basto was white with temper. The old man said a monkey who earned that word would hang his mother for a handful of peanuts and sell his tribe to an Italian organ-grinder for a piece of orange-peel.

"Basto lashed out then. His fist caught the old fellow on the jaw and knocked him unconscious. It was wrong to hit that old man. Very wrong! I wonder how Basto had the nerve to hit him. There was an invisible armor of tremendous age about the blind man, but Basto was mad.

"It took three of us to tear that Portuguese away from the old chap. The apes were screaming, and Basto was yelling out that he would kill the old fellow and every monkey in the menagerie. He fought and struggled with us as we carried him up to his room and locked him in. It was a bad business. A very bad business!

"That night something happened. That old man did not know that the baby of the gibbons was dead. He thought it was somewhere in the house, and in the night he went and opened the door of the cage in which the gibbons were, so that they could go and hunt for their little one.

"You would think those apes would make for the jungle when they were free, would you not? Not they! They remembered that little fellow, and they started to climb up the outside of Basto's palace, their long arms clinging to anything that helped them, and whimpering softly as they climbed. They thought they were going to get their baby back. They were only apes, but they had suffered. When I read of a kidnaping in the United States, I think of those two gibbons.

"They had some idea of the room where the baby had been taken. Perhaps they had heard him crying in the nursery. Perhaps they got the information in some other way. It is hard to tell how an animal finds out things. Often I have been puzzled. But those two knew. They knew.

"The window of the nursery was open. They climbed through without making a sound. A gibbon can move so swiftly and so silently that the lightest sleeper cannot hear him. He is swifter than the spider monkey, and the spider monkey is like lightning.

"Sleeping in the nursery was a Dutchwoman who was a nurse, and sleeping in a small cot near the nurse was Basto's little girl. And into that room came the two gibbons, wet-eyed, looking for their baby. Poor devils! Moving like ghosts, their arms being so long that their knuckles rested on the ground when they were walking upright....

"I have wondered a lot about those two apes—wondered how they knew that their baby was dead. Something must have told them. Softly, without the slightest noise, they searched that room. They turned over the cushions; they searched under the chairs and the tables. You see, it had rained that night, and in the morning we found the tracks of their feet on every inch of the floor.

"I have thought of them stopping at last to think what they could do to Basto. Stopping and rubbing their noses in the darkness.... Ja, you have guessed it! They did that! When the Dutch nurse woke in the morning, the bed of the little girl was empty!"

JAN KROMHOUT paused in his recital and spoke sternly to the

waw-waw, which had found a piece of old rag in his cage, and was

annoying the hanuman by wrapping it around his head in mockery of

the bandage on the little fellow's ear.

"Basto was really crazy then," continued Kromhout. "He offered a reward of one hundred thousand guilders. Five hundred men took up the search. They beat the countryside from Semarang to Djokjakarta, and from Soerabaja to Cheribon. It was a bad time for gibbons. Every ape those hunters met was in their eyes the kidnapper of Basto's baby. They were rough on the gibbons. They wanted Basto's money, and they did not ask questions. Not much.

"Basto started to drink. He would drink a bottle of schnapps each day. I took all the other monkeys away because he wanted to kill them. And the more he drank, the crazier he got. He thought that the big mias was waiting to kidnap him, and he would run round the house with a gun, thinking that an army of apes were in the place. Then one night he put that gun to his head and blew his brains out.

"After some months the hunt for the little girl slowed up. People thought that the gibbons had killed the child in revenge, so they gave up the search and went back to their work. You have seen the same thing happen in America. There is a big hue and cry, with everyone running this way and that, and big headlines in all the papers; then it begins to get stale. People do not talk so much about it; the papers print very little, and presently it is all forgotten. The world moves at such speed that the things of tomorrow wash out the happenings of today. We Dutch have a proverb that says Monday's gebraden rundvlees is forgotten when Tuesday's kalfvless is on the table. It is so....

"Six months after the death of Basto, his wife met with an accident on the Java State Railway when she was traveling to Madioen. She was taken to a hospital, but she died after an operation. No relatives could be found. Not one! So the big house at Solo and all the money in the bank were put in trust with the Dutch Government, in case the little girl that was kidnaped returned to claim it.

"People laughed at the idea of that little girl being alive. They thought it silly. The gibbon lives on leaves and fruit, with a lot more leaves than fruit, and you cannot feed a little girl on leaves. So people shook their heads and laughed when some one said: 'Perhaps she will be found some day.'

"Five years passed—ten, fifteen. I took a trip to Amsterdam to see my sister, who is married to a man who keeps a restaurant in the Stadhouders-Kade quite close to the Rijks Museum. I came back to Batavia, and from there I went up into the province of Bantam to trap kubins, the Galeopithecus volans, that you call flying-cats.

"I had forgotten all about Basto. I had no thoughts of the little girl that had been kidnaped by the gibbons.

"IT is strange country, that western end of Java. It is wild.

The forests have been left to themselves too long, and they are a

little frightening. The big trees, like the teak and rasamala,

shoot up to a height of one hundred and fifty feet, and they are

mostly covered with creeping vines that have flowers that look a

little vicious. And there are masses of moss and enormous fungi,

and there is silence. Quite a lot of silence. The only sounds you

hear are the sounds made by the wild pigs and the muntjak

deer.

"I was there two weeks when I heard a funny story. A native told it to me. He said that there was, in the very middle of the jungle, a hut in which lived a young Dutchman and his wife, and that this hut was known to the natives for miles and miles around as 'The House of the Apes.'

"'Why?' I asked.

"'Because the apes come and go as if they were friends,' he said. 'The young wife feeds them. They know her. If they are hurt or hungry, they go to the house.'

"I had little thrills up and down my spine when I heard that story. I was crazy to see that house. I asked a thousand questions. The hut was in the center of a clearing, the native told me, and he and dozens of other natives had squatted in the underbrush and watched the apes come from the trees when the woman called to them.

"I had work to do, but I could not work. That jungle bred thoughts that smacked of madness, I had to see that House of the Apes. I had to see the woman. I packed up my things, loaded my porters, and moved in the direction that the native gave me. I could not stop.

"I drove those porters eighteen hours a day. I thought—I thought that I was on the point of finding out that a miracle had happened. It was the kind of country where miracles might happen. Ja, it was. There were big red flowers on the lianas that were like eyes in the gloom, and the tussocks of moss cried out when you stepped on them. But the thoughts in my head were what upset me, not the jungle.

"It was dusk on a summer afternoon when I came to the edge of the clearing on which was the House of the Apes. I crouched in the underbrush and stared at it. There it stood on a square of green grassland that was hemmed in by palms and bamboos. It was raised on posts to keep it free of the white ants, and it was very quiet. Quiet and a little soothing.

"I am not religious. When I was a little boy, I used to go to the Oude Kerk and stare at the 'Adoration of the Magi' because I liked the color of the stained glass; but a lot of years had passed between then and the moment I stood and stared at the House of the Apes. Yet I muttered a little prayer as I watched that building. Do you know why? I thought I was going to find out that a miracle had taken place! A great miracle.

"For a long while I waited—waited for the door of the house to open. The dusk was purple. There was a tremendous silence in the clearing. Then—then when my nerves were stretched till they hurt, the door opened, and she was standing on the little platform above the ladder.

"A girl, slim and graceful like the kantjil deer. She had two plaits of black hair falling down on her kabaya, and her bare legs and feet showed under a red sarong. And in the soft dusk she looked a little unreal. She was—she was like an apparition. Do you understand? I rubbed my eyes and looked again to make sure that she was there.

"Some one called from the jungle, and she answered. Then I saw that young Dutchman. He was in the late twenties, tall and strong. He came into the clearing at a run, and the girl skipped down the ladder to meet him. I watched them from the underbrush. I was looking at something that made me think of the world when it was young. Something that was sweet and clean, something that was far away from the filth of cities.

"Standing together, their arms around each other, the girl gave a call that startled me. The trees around the clearing became alive. Alive with apes—with lutungs, gibbons, macaques, and little lemurs! They slipped down from the trees and ran into the clearing. They raced around the girl and the man. She brought them food and played with them. And the little lemurs fought with each other to reach her hands.

"Once I saw a picture of Adam and Eve in the Garden with all the animals around them. It was just like that. In the soft dusk of the summer evening! It made me a little tearful as I watched. A little lonely. I thought I had missed something—something worth more than all the money in the world. Love, I thought it was. I was not sure.

"WHEN they went up the ladder, I called to them, and I walked

into the clearing with my porters. I told them who I was, and the

young man said he had heard of me. They asked me into the house;

and when I saw that girl close up in the light of the candles, I

wanted to cry. Ja, I had to wipe my eyes a lot. It was

strange, that business. I was looking at the image of the wife of

Josť Basto.... I had a funny feeling in my inside. Just a little

sick, and a little frightened about the ways of the

Almighty....

"After we had eaten, we sat on the platform of the house and talked. There was a big red moon. Now and then you would hear an ape tell his mate to move over so that he would have a little room. And into the soft silence the young Dutchman put scraps of his life to please me. He knew I was curious.

"He had been there since he was a little boy. His father had built the house. The father was a great botanist from the University of Leyden. He had written many books—books on the ferns and fungi, and on the big trees, the sun-wood, the upas, and the Pterospermum javanicum.

"My ears were as big as the shells of the giant clam as I listened. He was so slow in his speech—so very slow. The girl fell asleep, her back against the bamboo frame of the house, her bare legs stretched out. She was very pretty.

"THE man looked at her with a smile; then he started to tell

that which I was waiting for—started to tell of the

miracle—in a low voice so that he would not disturb

her.

"He was ten years of age at the time. Young, but he had been brought up in the jungle. One day he was close to a river that was some two miles from the house, when he heard a great hubbub. He ran to see what was taking place, and he saw about twenty apes trying to pull something out of the current, and howling with terror because the job was too much for them.

"The boy thought at first that it was the baby of one of them; then he saw it was a little girl. He jumped into the water and grabbed her, but the current was too strong. He was swept down the river for a mile or more; then he managed to get ashore on a swampy island. He thought the child was dead, but he worked her arms backward and forward till she opened her eyes and looked up at him.

"The apes had followed along the bank of the river, and they were howling like the mischief because they could not get to the little girl. They had blundered in crossing that river. They had climbed out on the big limbs over the water, but when they were swinging the child from one to the other, she fell into the stream.

"The boy and the girl were on the island two days before the father of the boy found him. They brought the little girl back to the house in the clearing, and all the apes followed them. They were not annoyed, those apes. They were pleased—very pleased with the boy.

"AND the girl grew up with the boy. They did not know her age,

but they thought she was about three years old when they found

her. And as she could not speak any language but the chatter of

the apes, she could tell them nothing. Nothing at all!

"After she had been with them thirteen years, the old father was taken sick. He had a wish that those two could be married before he died. That was his desire. The boy set out for Laboean, that was fifty miles away, and with only a jungle path leading to it. He found a missionary, and he brought him to the house in the clearing, and the boy and the girl were married....

"When he had told me all that, he looked around at the sleeping jungle, and the big red moon. It was very beautiful. There was a magic there that I had never felt before. A strange magic. It came from the earth, from the trees, from the love of those two....

"He turned to look at his wife, who was sleeping softly. He smiled as he watched her. His hand stole out and touched her kabaya. Gently. He glanced at me, and I looked away quickly. He was much in love, was that young man. Very much in love. The world was his world. I felt a little jealous. He was like Adam. He had everything.

"After a long silence I got up and went quietly down the ladder. In the morning I left before they were up. I did not wish to intrude in their—Nee, I told them nothing! Nothing at all! What was a million guilders to them? Nothing! When he was telling his story to me, I felt as if the Almighty had drawn a string around my throat. Gently, but tight enough to stop me from speaking. It was a hint. The Almighty knows His own business. Ja, you bet! He did not wish an old fool of a Dutchman interfering. Sometimes—sometimes when I think the world is a sad place, I remember that man and that woman in the House of the Apes. It does me good to think of them."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.