RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

"TheSunlessCity," F.V. White and Co., London, 1905

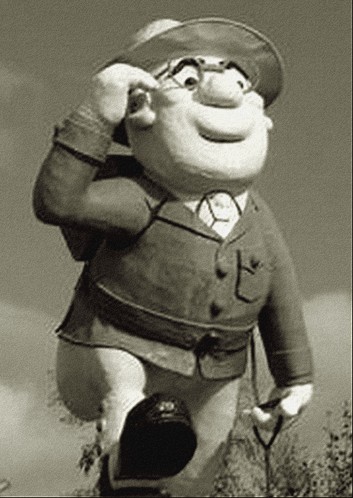

The Sunless City: From the Papers and Diaries of the Late Josiah Flintabbatey Flonatin (or simply The Sunless City) is a dime novel written by J. E. Preston Muddock in 1905. The novel is about a prospector named Josiah Flintabbaty Flonatin who explores a bottomless lake in a submarine, and discovers a land where the norms of society are backwards. The title character is the namesake for the city of Flin Flon, Manitoba, Canada. — Wikipedia.

"Alph, the sacred river, ran

Through caverns measureless to man

Down to a sunless sea."

IN one of the loneliest and most inaccessible parts of the Rocky Mountains of America is situated a strange lake or tarn.

The lake lies "silent, still and mysterious in the bosom of the everlasting mountains, like a gigantic well scooped out by the hands of genii."

There is no herbage; no animal life on its shores or in its depths. The unbroken stillness of death reigns there.

For generations learned and scientific men puzzled their heads about this mysterious sheet of water which takes all in, but apparently lets nothing out, for there is no known outlet by which the water can flow away, and owing to its peculiar situation the evaporation is very trifling, as the sun's rays seldom pierce the gloomy depths. Some stated that it was the crater of an extinct volcano, and that fissures in the mountains carried off the surplus waters, to discharge them again either in the sea or some other lake. Again, it was argued that a huge cavern was the escape valve, and a subterranean river was the solution of the problem; while another theory was that the rocks were peculiarly porous, and absorbed the water, which issued from the earth again in the form of springs many miles away.

It will thus be seen that it was the debatable ground for savants in various parts of the world. Philosophers with the whole alphabet of letters after their names advanced theories which were immediately denounced as "bosh" by other philosophers, who claimed the right to put a string of capitals after their names also. Stormy discussions, distressingly clever papers, and huge volumes of learned writing were the result of this natural problem. While the wiseacres, however, were thus squabbling about the correctness of the various theories advanced, a certain gentleman was seeking for a more practical solution of the mystery.

Josiah Flintabbatey Flonatin, Esq., or, as he was more familiarly known amongst his fellows, "Flin Flon," was a gentleman conspicuous for two things—the smallness of his stature and the largeness of his perception. His origin was lost in the mists of antiquity, but he boasted that he was a descendant of the noble Italian family of the Flonatins, for centuries resident in the ancient city of Bologna, who were conspicuous for their learning and power during the Middle Ages. Being unfortunate enough to espouse an unpopular cause during a revolution they were stripped of their power, deprived of their wealth, and banished, many of them dying in exile and poverty. Possibly, if his pedigree had been traced, the statement might have been proved correct, but it is sufficient for the purposes of this veracious history to say that at this time Flin Flon was a grocer in a small way of business. In recording the fact I hope it will not be thought that a slight is intended upon the memory of a great man. Flin Flon could not help being a grocer. His father and grandfather before him had been in the same line—or, as they were pleased to term it, "profession"—and the business had been handed down from father to son through several generations. But that was in the good old times when men did not trouble themselves about the abstruse sciences or the laws of unknown quantities. And when, instead of attempting to soar into regions of speculation about the mysteries of the universe, they were content to smoke the pipe of peace in the cosy chimney corners of the country inns.

The business to which Flin had succeeded on his father's death was a snug little concern. There was a very profitable cheesemongery and bacon trade in connection with it, chiefly amongst country families, who wanted long credit but were content to pay a big price for the accommodation. And it was said that the profits on this branch of the trade were as much as eighty and ninety per cent.

Such paltry profits were scarcely worthy the consideration of a philosophic mind. At any rate one thing is tolerably clear, Josiah Flintabbatey Flonatin began to neglect his business and to frequent debating and other learned societies. Some ill natured persons said that this was owing to a "disappointment." They hinted at an engagement between Flin and a buxom widow, who proved false to her plighted troth and married a very worldly farmer, her excuse being that she thought Flin Flon was a "little cracked." This perhaps was a malicious scandal.

It may very safely be inferred, however, that the true cause of the good man's disgust for his progenitor's grocery business arose from the fact that he had a soul above sugar and spice, and cheese and bacon. No disparagement to the trade in these excellent commodities is meant by this remark. Flin Flon was born to do great deeds, to become a hero whose name should pass with honour.

"Down the ringing grooves of time."[*]

[* "Let the great world spin for ever down the ringing grooves of change." —Alfred Tennyson, "Locksley Hall," line 182.]

At least this is what he told his friends. He was

desirous of living in the memory of men, and being intellectual

he was destined to make his way in the world, which he succeeded

in doing in a very remarkable manner, as will be hereafter seen.

In fact no man before or since has ever made his way in the world

in such an extraordinary fashion.

Flin laboured hard for the advancement of science, and when but a young man he became a Fellow of the "Society for the Exploration of Unknown Regions," and it was with no small degree of pride that he placed after his name the imposing array of capitals, F.S.E.U.R., and was always particularly careful to write them boldly, so that the possibility of their being overlooked or mistaken was out of the question.

Flin's election to this ancient and learned body was a very distinguished honour, and was a fitting tribute to the man's great genius. There were a few of the members who vigorously opposed his election, on the grounds that to admit a "common grocer" into their Society was to bring them into disrepute. But it is gratifying to be able to say that this opposing faction represented but a paltry minority, and the subsequent and glorious achievements of the immortal Flonatin covered his enemies with shame and confusion, so that they were glad to hide their diminished heads in obscurity.

In personal appearance Flin Flon was as singular as his name. When Nature constructed him she must have suddenly run short of materials, because she commenced a head that would have done credit to a giant in stature as well as intellect. But getting as far as the neck the old dame found apparently she had made a mistake, so finished him off hurriedly. From the neck downwards he was strangely disproportioned and very scanty.

He had pendulum-like arms; a body that might have been taken for a section of a fourteen-inch gaspipe, and legs that may not inaptly be described as corkscrews.

He was bald—almost perfectly bald. But then all intellectual men are bald.

Another infallible sign that Flin was possessed of extraordinary brain power, was that he always wore spectacles. He was never known to be without them, although his eyes did not indicate that he was troubled with either long sight or short sight. On the contrary, judging from their keenness and brilliancy, it might be said, to use a very common metaphor, that they were quite capable of seeing through a millstone. But then clever men always do wear spectacles.

His nose was large, exceedingly large, and it was rather conspicuously red.

His face was somewhat long and thoughtful. Near the right-hand corner of the mouth was a mole, from which sprang a few silver hairs, and under the left eye was a tiny pimple.

In age Flin Flon was nearly forty when he undertook the astounding journey which has immortalised him.

He had many virtues and a few vices, and one of the latter was an inordinate love of snuff.

Whatever pride of birth Flin had, he certainly had no pride of personal appearance. But is not this another sure and certain sign of genius? Slovenliness and cleverness go together.

Tightly-fitting smalls and an old faded green coat closely buttoned up to the chin were Flin's invariable costume. And when out he wore a broadbrimmed hat, which set off his genial and intelligent face to advantage.

It happened that amongst the hundred and one things that Flin Flon interested himself in was the mystery of the strange tarn away in the Rocky Mountains, and on one occasion he had had the boldness to organise a little band of daring adventurers who started on an expedition to examine the lake by means of a boat, and report thereon. The boat was the great difficulty, for not only were there no roads, but the water could only be reached by means of a tortuous and dangerous way down the jagged ledges of rock near the waterfall. But with the enterprise and determination so characteristic of the man, Flin Flon had a small boat constructed in sections, and conveying these by rail to the nearest point, he engaged the services of a party of friendly Indians, and by their aid the boat was safely launched on the bosom of the dark waters, and thus the lake was thoroughly explored.

When the adventurous voyagers found themselves afloat, it was impossible to suppress a shudder. Far above them the sky could be seen like a little square patch of blue. A weird gloom pervaded the place, and the air was cold and damp. Not a blade of grass, not an herb of any description could be seen, and the voyagers proved that there was no life in the water, for every means were tried to catch fish, but there were no fish there, and microscopical examination revealed the fact that there was not a trace of animalculae. Round and round the mysterious lake the boat was pulled, but no outlet for the water could be discovered. What then becomes of the surplus? was the question these savants asked one of another, but the answer was not forthcoming. Flin Flon was silent on the subject. He offered no remark, he suggested no theory. But in his great brain a thought was taking shape, that when the time came to clothe it in words was destined to startle the world. Soundings were tried for. A hundred fathoms of line were let out. Then two, three hundred, a thousand fathoms, and when two thousand fathoms were gone one and all cried, "Alas! the lake is bottomless."

The expedition having resulted in no scientific or geographical discovery, the learned "Fellows" were compelled to return, having first named the place Lake Avernus. At the first meeting, after the return of the adventures, of the "Society for the Exploration of Unknown Regions," the public flocked in hundreds, so anxious were they to have some account of the tarn which had puzzled the learned and the scientific for generations. But great was the disappointment when it became known that the combined intellect of the members of the expedition had not been able to solve the problem, and that the mystery was as much a mystery as ever.

The Society's great hall in New York, where this meeting was held, was packed from floor to ceiling with a brilliant assemblage of the most learned geographers, professors, and scientists that the world could produce, and they were not slow to express their sorrow when they learnt that the object of the expedition had not been attained.

There was one of the members who had as yet made no observations, though it was notified on the Society's programme that this gentleman would read a paper on "Lake Avernus and its probable outlet." The gentleman was Flin Flon, and his rising was eagerly looked for, as something good was always expected from him, while his wonderful intuitive perception enabled him to arrive at theoretical conclusions which were often startlingly accurate.

It was late in the evening when the Chairman, in an appropriate and neat speech, introduced Josiah Flintabbatey Flonatin, Esq., to the notice of the meeting, alluding in graceful terms to the great benefits this gentleman had already conferred upon the scientific world by his energy, determination and wonderful powers of intellect. And he (the Chairman) felt quite sure that the meeting would listen with eager interest to the paper Mr Flonatin would now have the honour of reading.

The meeting fully endorsed the Chairman's flattering remarks by a storm of applause that did not subside for some minutes.

Then the great Flin Flon arose, calm, dignified and grave. By the chair beside him reposed his large gingham umbrella, and in Josiah's hand rested a huge gold snuffbox, bearing an elaborate inscription, setting forth that the box had been presented to the present owner by "a circle of friends in acknowledgment of the great services rendered to science by Josiah Flintabbatey Flonatin, Esq., and as a token of respect for one whose wisdom and rare intellectual gifts, combined with largeness of heart and the kindest of natures, have won him troops of friends."

When the meeting had settled into silence again, and Flin Flon had refreshed himself with sundry pinches of the fragrant dust from the gold box, he straightened the wrinkles out of the green coat that was tightly buttoned round his gas-pipe like body, and with two or three swings of his pendulum arms, as if thereby he set the vocal machinery in motion, he commenced his "paper," having first placed his much-prized umbrella on the little table before him.

"Mr President, learned Fellows, and ladies and gentlemen,—I have the distinguished honour of appearing before you to-night as a member of this ancient Society, but I must also add with regret as a representative of the expedition to Lake Avernus, whose mission has entirely failed practically."

"In dealing with the subject in hand it will be necessary for me to digress somewhat, but I respectfully claim your indulgence on this point, and hope that what I have to say will not altogether be uninteresting."

"It is a well-known fact, ladies and gentlemen, that we live upon a globe; that is, on the external crust of a huge ball. There is one thing which science has proved beyond all doubt, and that is, that this ball is not solid but hollow. Now the capacity of that hollow must almost be beyond comprehension. From time immemorial it has been supposed that the hollow is filled with seething fire and molten lava. I say supposed, because it is only a supposition. But I boldly denounce the theory of internal fire as incorrect. I say science has been at fault. Central heat is a delusion unworthy of the consideration of great men. And now having demolished the monstrous and ancient fable with one blow, I have a theory of my own to advance that will startle you. I know it will, but I cannot help it. Nay, it is more than a theory, it is a conviction; and I say that in the centre of the earth are subterranean rivers and buried seas; more than that, ladies and gentlemen, I go so far as to say that the interior of the earth is as likely to be inhabited as the exterior."

Flin Flon paused. He took snuff excitedly. His audience, however, remained silent. The daring proposition had awed them.

"To resume."

"By the light of science it has further been revealed to us that the crust of the earth upon which we stand in no part attains a greater thickness than fifteen miles; and it is stated as a scientific truth that if we could dig down to that depth, and break through the inner surface of the crust, we should come to fire. I assert that that is a monstrously absurd theory; that we should do nothing of the kind, but that we should break in upon a new world, a new race of beings. That we should find a land of beauty and fertility; that we should find rivers, seas, mountains and valleys. The inequalities of the bottoms of our valleys will form mountains there; and our mountains will be their seas. Like unto a pudding-mould, whereon the fruit and flowers are convex on one side and concave on the other."

Flin Flon had worked himself into a state of enthusiasm and excitement, and as he gave utterance to the clever simile he caught up his favourite umbrella, and with a wild flourish brought it down again on to the table, shivering the water decanter to atoms, and just shaving by a hair's breadth the nose of the President, which was rather a large one.

This was the signal for a burst of applause from the audience, that was mingled with loud shouts of disapproval. The excitement was intense. The densely packed masses of people rose and swayed backwards and forwards. Some few persons cried out,—

"No, no."

"Humbug."

"Absurd."

"What has this to do with Lake Avernus?"

When Flin had wiped his heated brow with a large bandanna handkerchief, and restored himself to composure by a dose of snuff, he again addressed the assembled multitude.

"In commencing my speech," he went on, "I told you I should digress, and I asked your indulgence; but I may state here that the theory I have set forth has everything to do with Lake Avernus. I say fearlessly, I say, ladies and gentlemen, that this mysterious tarn is the entrance to the inner world."

Again the cheers and discordant cries broke forth, and the audience grew more and more excited. Ladies waved their handkerchiefs frantically for it may be parenthetically stated here that Flin was a great favourite with the softer sex— gentlemen tossed their hats up, and other gentlemen sat down upon them and crushed them into an unrecognisable mass. Such a scene had never before been witnessed in the Society's hall; but Flin preserved his composure. He stood as firm as a rock. His right hand was inserted in the breast of his green coat, and his left toyed with the gold snuff-box.

The attitude of the wonderful man must have been a study, and it is much to be deplored that no one amongst that assembly of clever men and women had sufficient presence of mind to whip out paper and pencil and sketch Flin as he then stood. The picture would have gone down to posterity as the most precious relic of a brilliant orator and distinguished savant.

When silence had once more been restored he continued his address.

"Pioneers in knowledge, like pioneers in exploration, have always to endure great hardships, but I know my fellow men too well to expect to meet with no opposition. I am, however, prepared to brave that opposition, to stand firm to my faith, and, if needs be, to lay down my life in the glorious cause of attempting to extend our knowledge of the earth we dwell upon. I repeat that the interior of the globe is inhabited. By what kind of beings I am not prepared to say. They may be monsters; they may be pigmies, or both; but that is a question I hope to be able to answer at some future day. Ladies and gentlemen, as the Creator has adapted a race of beings to exist on the surface of the earth, I fearlessly assert that He may have adapted a race to exist in the interior. If I have startled you by the boldness of my propositions, I shall startle you still more when I say that I intend, at all hazards, to attempt, in the interests of this honourable Society and the world at large, to penetrate into the bowels of the earth."

"How, how?" arose from a hundred throats. "By descending to the bottom of Lake Avernus."

"Impossible! impossible!" cried the audience.

"Nothing is impossible to the resolute and energetic man of science. If I fail in my project I shall be but one more martyr added to the many who have been sacrificed in a noble cause."

Flin said this very proudly, and took snuff with the air of one who felt that he was destined to reveal great and startling truths to unenlightened mankind.

"I now come to the third and last part of my address," he went on, "which deals with the means I propose to adopt to find the answer to this knotty question. I intend to have a small boat constructed upon peculiar principles, the details of which it is unnecessary to enter into here. Suffice to say the boat will be built upon a principle never yet applied. It will be sufficiently large to contain myself, a few animals, and stores to last for a month. By an arrangement, which at present I intend to keep secret, I shall be enabled to create sufficient pure air to enable me to live, while a series of valves will discharge the foul air, and give me the power of rising or sinking the vessel at pleasure. If my theory of the subterranean river be correct there will be, on reaching a certain depth of the lake, a strong current setting towards it. My vessel will be carried along by this current, and before the month has elapsed I shall emerge again somewhere in mid-ocean or find myself in a new world."

"Or be food for fishes," exclaimed a voice in the centre of the hall.

"Possibly so," Flin answered. "But it will be some satisfaction to my friends to know that I sacrificed myself in the glorious cause of science; that I am but one more martyr added to the already long list of those who have unselfishly devoted themselves to the enlightenment of their fellows. I am desirous of extending our knowledge; of writing another page to the history of the world of wonders. Moreover, if there is a race of beings inhabiting the centre of our globe, they may be living in a state of spiritual darkness. And in that case I should make arrangements to send a number of missionaries in to them. They may be naked and cannibals. Then I should clothe and civilize them. In short, I deem it to be my duty to endeavour to solve the great problem as to what is in the interior of the earth; and I shall not flinch from that duty. Ladies and gentlemen, I shall devote myself to the cause, and if I perish I shall perish nobly."

He resumed his seat amidst a storm of applause. Even those who differed from him could not but admire the undaunted courage of the little man.

A vote of thanks to Flin Flon was proposed and carried unanimously, and the Chairman stated that in a few days further particulars would be announced in reference to the daring scheme proposed by that gentleman, whose experiments would be carried out under the auspices of the Society for the Exploration of Unknown Regions.

ON the following morning all the papers published long accounts of the meeting of the Society for the Exploration of Unknown Regions, and of Flin's strange proposal. Nearly every journal had a weighty editorial article on the subject. Some denounced the scheme as impracticable and the emanation of a madman's brain; while others were strongly in favour of it, and thought the plan quite feasible.

The excitement in New York City was intense. Flin Flon's lecture was the one topic of conversation. Everything else seemed to be forgotten. The startling theory advanced by the lecturer, and the boldness of his proposition, had broken upon the city with the suddenness of a thunderbolt. It is to be doubted if even a volcano in the centre of Broadway could have caused more astonishment. Everybody exclaimed to everybody else,—

"Is it not wonderful?"

"How strange to be sure!"

"I wonder that it has never been thought of before."

All the papers published special editions in the afternoon, containing every scrap of information bearing upon the subject. It was a rich harvest for the penny-a-liners. With the indefatigable energy so characteristic of these gentlemen, they rushed about from one end of the city to the other; a few of the most zealous even neglecting their usual forenoon "nip," though it must be confessed that the few represented a very small minority indeed, as the greater number of these "gentlemen of the Press" made the occasion one for indulging in sundry other nips, over and above the usual matutinal dram; and it is highly probable that the news which was published for the information of the public was nearly all concocted in the liquor stores.

In Wall Street, and on the Exchange, the speculators, the hangers-on, the penniless stockbrokers, the gamblers in scrip and shares, seemed to quite forget their ordinary business and go mad upon the all-absorbing topic. Several daring and needy speculators offered to form a limited liability company, to be called the "Central World Exploration Company (Limited)," with a capital of twenty million dollars; and in the event of success attending Flin's adventure, and if inhabitants were discovered, the company were to take steps to open up commerce with them immediately. This proposal, however, did not meet with any very favourable reception, as the projectors were known to belong to that clique which fatten and batten upon the public, and take advantage of every excitement to float bubble companies, by which nobody profits but the promoters, and they make big fortunes. In fact, these very men would have undertaken to have formed a company to be called "The Lunar Steam Navigation Company," its object being to run a daily service of first-class, high-pressure steamers, carrying goods and passengers at cheap rates, from the earth to the moon. Nor would they have wanted shareholders, as fools and their money are soon parted; and persons are always to be found who are ready to subscribe to the most Quixotic expeditions that were ever planned.

However, in this instance, the "Central World Exploration Company, Limited," scheme did not meet with general approbation, although a few persons expressed their willingness to subscribe. But one enthusiastic and shrewd Yankee offered to risk three thousand dollars' worth of dry goods in the proposed vessel, and to commission Flin to dispose of them to the best advantage to the Central Earth dwellers, should he find any; while a benevolent and philanthropic old lady, who was well known for her piety and charity, undertook to supply Flin with fifty dollars' worth of suitable tracts for distribution. A celebrated firm of distillers offered him a very handsome commission if he would undertake to introduce their far-famed and noted Bourbon whisky to any people he might discover; while Professor Bolus, the universally known pill and ointment man, most generously agreed to allow the explorer fifty per cent. upon every box of pills or ointment he might dispose of. And "The Great Monopoly—do all and buy up everything Company," intimated their willingness to appoint Mr Flonatin their chief agent in the centre of the earth, should he discover any people dwelling there.

If fact, these and similar liberal offers continued to flow in for some days, but it is almost needless to say that they were one and all firmly but respectfully declined.

During all the excitement, which continued for some weeks—the papers taking every opportunity to keep the agitation up to boiling point—Flin Flon was quietly superintending the construction of a curious vessel, the design of his own ingenious brain. One of the largest New York firms of engineers was carrying the work out. And so day by day, while the populace were growing more excited, and the journals teemed with letters on the subject pro and con., Flin's fish, as it was hereafter to be know, was rapidly nearing completion, and at the expiration of six weeks from the delivery of the address at the Society's meeting, the finishing touches were put to the strange vessel, and it was at last placed on view at Barnum's Museum, Mr Barnum having magnanimously consented to defray all the expenses of the construction of the vessel solely on condition that it should be exhibited in his museum for a certain time as soon as it was completed. An extra quarter dollar admission money was charged to the public during the time it was on view. But they would willingly have paid treble that amount for the privilege of seeing the wonderful vessel.

The shape of it was that of a huge pike, thirty-four and a- half feet long from the extreme end of the tail to the tip of the snout. The diameter was eight feet and a-half in the thickest part. The fish was constructed of small copper plates, beautifully joined together by countless numbers of minute rivets. In the interior was a casing of sheet-iron, and between this and the internal walls of the machine a space of a foot in width was left for the purposes that will be presently explained. In the exact centre of the fish was a crank made of highly- polished steel, which could be connected or disconnected at pleasure. And owing to an ingenious system of counterweights, the slightest manual labour would cause the crank to revolve freely. This crank communicated with a small pair of patent-float paddle wheels, so that the occupant of the machine could propel the vessel under water. The diameter of the wheels was three feet. The frames were composed of galvanised steel and the floats of mahogany, the edges being protected by brass plates.

The fish was so constructed that it would descend to any required depth head first. The centre of gravity could then be brought to the belly of the fish by moving a lever which acted upon a hydraulic pump, so that the vessel would float horizontally, and by means of the paddles could be driven along under water, at no matter what depth, the speed averaging from five to seven knots an hour.

It will be necessary to explain here that this alternation in positions from perpendicular to horizontal, and vice versa, was effected in a very ingenious manner by means of ballast, the ballast being water contained in the iron tubes that were placed between the outer skin of copper and the inner skin of sheet- iron. The water was acted upon by compressed air.

In the event of the voyager wishing to rise to the surface at any moment, he opened a valve and the compressed air would force the water out. The machine would then rise; while a suction-hose, worked by a small hand force-pump, gave the occupant the power of filling the ballast tubes again, thereby causing the fish to sink once more into the watery depths. In the head of the vessel were place two large eyes, constructed of thick plate-glass, protected by fine copper netting. Each eye was constructed to hold a small electric lamp. This lamp consisted of a piece of platinum wire, connected with a coil for producing currents of induced electricity of great intensity. The coil was of copper wire insulated by being covered with silk, and could be instantly connected with a very powerful voltaic battery. When the apparatus was in action the platinum became luminous, and produced a white and continued light that penetrated the most profound obscurity. These lamps, being very small, could also be carried by the traveller in a small leather case, which was hung around his neck, a miniature battery in this case being used.

The tail of the fish was so arranged that it could be used as a rudder, and was worked from the inside by means of a wheel placed in the head, thus enabling the traveller to keep a lookout and steer at the same time.

The internal arrangements were as near perfection as human skill and ingenuity could make them. In the tail was a small iron reservoir containing a combination of chemicals, which by a process of very slow decomposition evolved the properties of oxygen and hydrogen in such proportions as to keep up a constant supply of pure air inside the fish, while the carbonic acid gas was forced out by a complicated arrangement of pipes which communicated with the mouth of the monster, and were so constructed with trap valves that while allowing the bad air to escape they did not admit the water. It was estimated that this reservoir contained a sufficient amount of chemicals to last for two months. At the end of that time the vessel could be brought to the surface, and the reservoir refilled from a spare store. In the neck was a circular flooring, occupied by the voyager during the descent. When the fish was horizontal this formed a bulkhead, to which was attached a bunk that could be closed up or opened out at pleasure. The gills were represented by two oblong slits of strong plate glass, so that a clear lookout could be obtained. There were also two small windows in the tail.

The centre of the vessel was fitted up as a storeroom, laboratory and study. Here were compasses, a barometer, several thermometers, and a brass dial plate, in the middle of which was a delicately-poised hand. The plate was marked with a graduated scale, and the hand was connected with a strong spring. This again was enclosed in the tube, the mouth of which projected from the back of the fish. Inside of this was a balance which was depressed by the weight of water, so that the exact depth was accurately registered on the dial plate. There was also a somewhat similar plate for registering speed, and a peculiar clock for marking off the days. By closing a door at each end of the compartment it could be made perfectly water- tight, a measure rendered necessary by the possibility of an accident occurring to the head or tail. In the hinder part was a series of lockers to hold provisions sufficient to last for three months. In various parts of the inside there were also placed bottles of prepared phosphorus, which emitted a soft and pleasant light, so that the venturesome traveller was not altogether dependent upon his electric batteries. Each compartment was comfortably fitted with seats, the roof and sides being luxuriously cushioned and padded. There was also accommodation provided in the stern for a few birds and small animals.

During the time that this remarkable and ingenious vessel was on view, enormous crowds flocked to the museum to see it, and the astute Barnum netted vast sums of money; though it must be told, to his credit, that he generously placed one per cent. of the receipts at the disposal of Flin towards the expenses of the expedition.

A day or two before the time for Flin to take his departure, he and the other members of the Society for the Exploration of Unknown Regions were entertained to a grand banquet by Mr Barnum, which was given at Astor House, in the Broadway, New York. With his usual liberality the genial showman sent a free ticket to each newspaper, and there was a very strong muster of Pressmen.

All the elite of New York society were there, and a gallery was fitted up at one end of the hall expressly for the accommodation of ladies. And such a galaxy of youth and beauty had seldom been brought together under one roof. It was jocosely remarked by a certain wag that the enterprising Barnum had taken care to send tickets to those ladies only who were noted for youth and superb beauty.

Perhaps this was true, for more lovely and enchanting creatures it would be difficult to imagine. The bright eyes, the bewitching smiles of the dainty mouths, the snowy necks, the well- formed arms, and heaving busts of those fair women, caused them to be the cynosure of all the male sex; while as for the diamonds that sparkled in the hair and on the necks of the lovely creatures, they produced an effect that is indescribable, though one of the reporters spoke of it—

"As a scene of exquisite loveliness. It seemed as if the angels had gathered all the early dewdrops from the roses in Eden, and then scattered them with a lavish hand amongst this group of earth's fairest creatures; illuminating them with luculent rays of great purity, caught up from the jasper river that rolled its course through the peaceful plains of heaven, these rays produced a hundred prismatic hues, dazzling the beholder, and helped to complete a scene that mortals could gaze upon only once in a lifetime."

This was a little too flowery, but then it was pretty and peculiarly American. The guests numbered nearly a thousand.

Of course the toast of the evening was "The Health of Mr Josiah Flintabbatey Flonatin, and success to his bold undertaking."

Flin responded very briefly. His bashful and retiring disposition would not allow him to say much about himself. But he expressed the strongest hopes of the success of the undertaking, and said that he was determined to either succeed or perish.

This brought forth a storm of applause, and the ladies, dear creatures, waved their scented cambric handkerchiefs at the speaker. And one beautiful girl of about nineteen summers was heard to murmur,—

"Wal, I guess that licks creation, it does. I should like to hug the old man, I should, God bless him!"

In her enthusiasm she drew a magnificent little bouquet that had reposed on her fair bosom from the front of her dress, and pressing the gorgeous flowers to her lips, she leant over the front of the gallery and gracefully cast the bouquet down to Flin.

The face of the great man was suffused with blushes as he stooped and picked up the flowers, pressed them to his lips, bowed low to the charming little lady, and then placed them in his buttonhole. This act was the signal for another burst of cheering that did not subside for some minutes.

When order had once more been restored, Mr. Barnum rose to his feet to give the toast of "The Society for the Exploration of Unknown Regions."

He alluded in graceful terms to Flin Flon. He was a man of whom everyone ought to be proud, and he firmly believed that he would succeed in carrying the glorious stars and stripes into the very bowels of the earth. At anyrate, if the attempt failed, it would be another bright page added to the history of American enterprise. He felt that he could not sit down without taking the opportunity to contradict, in the strongest and most indignant terms, a scandalous report which had been published in some low English journals, that he (Mr. Barnum) had got up this affair as a money-making speculation, and that the whole thing, from beginning to end, was a swindle and a humbug. The idea was not his but Mr. Flonatin's, and though he had lent his museum for the purpose of exhibiting the wonderful vessel, the designs for which had had their birth in the giant brain of the originator of the expedition, he had done so purely in the public interest. He felt proud that Mr. Flonatin was a New York citizen, and he hoped that every gentleman of the Press then present would not fail to inform the Britishers, who were eating their hearts with envy and jealousy, because they had no Rocky Mountains and no strange tarn, that this bold scheme was originated by an American gentleman, and was worthy alike of him and American enterprise.

Mr. Barnum resumed his seat amidst a perfect hurricane of applause, even the ladies joining in the cheering, waving their fans, and clapping their hands in their excitement.

The banquet came to an end at last, as all things must; but it was with the greatest reluctance that the guests departed from that hall of beauty. In going into the streets it seemed like passing at one step from the realms of fantasy and fairy-land to the murky regions of a nether world.

WHEN the morning dawned for Josiah Flintabbatey Flonatin to leave New York with his novel craft, the excitement and enthusiasm of the people rose to an extraordinary pitch.

Business was entirely suspended. The militia and the police were drawn up in double file along the whole of the route through which the expedition was to pass. The windows and roofs of all the houses were crowded with people. The streets were gaily decorated with flags, and bands of music were stationed all along the route, and played "See the Conquering Hero Comes" as Flin Flon approached.

Mr. Barnum was determined that nothing should be wanting to make the affair one of an imposing nature, and so he had at an immense expense procured a white elephant. Some snarling cynic avowed that the animal had been whitewashed for the occasion, but Mr. Barnum was not likely to have lent himself to any such imposture. On its back was placed a magnificent howdah, with curtains of cloth of gold backed by blue satin. In this howdah Flin Flon was seated, and behind him marched another elephant, carrying the strange fish vessel. Then came a long string of carriages, bearing the members of the Society for the Exploration of Unknown Regions and their friends—that is, the friends of the members, not the regions. In many of these carriages were ladies superbly attired, for Flin was an especial favourite with the ladies, and they had taken an unflagging interest in the object of the expedition. Mr. Barnum and his company from the museum brought up the rear. The company included a giant nine feet high, two dwarfs, four Circassian ladies whose hair reached to their feet, two wild savages from the Carabboo Islands (an obscure English journal said that these savages were natives of Wicklow, in Ireland, but there is no doubt it was an unfounded and malicious statement)[*], a two-headed woman, who, it was said, could talk in two different languages at one time. It was commonly reported that she had been married three times, but each of her husbands, poor fellows! had died raving mad. There was also a bearded lady, an armless man, who wrote and did everything with his toes, and a spotted Ethiopian, so that there was altogether a very fair collection of lusus naturae.

[* Likely a reference to an early 19th century impostor who stated she was Princess Caraboo from the island of Javasu in the Indian Ocean, but was actually a cobbler's daughter Mary Baker née Wilcocks from Witheridge, Devon. Her story was the basis of the somewhat fictionalized 1994 movie Princess Caraboo. Her case was originally reported in: Gutch, John Matthew. 1817. Caraboo. A narrative of a singular imposition, practiced upon the benevolence of a lady residing in the vicinity of the city of Bristol, by a young woman of the name of Mary Willcocks, alias Baker, alias Bakerstendht, alias Caraboo, Princess of Javasu. London: Baldwin, Craddock and Joy.]

One of the great railway companies had offered to convey the vessel to Lake Avernus free of cost, and when the station was reached a special train of cars was in readiness for the embarkation of the expedition.

Some considerable time was taken up in getting the expedition on board the cars, but at length it was safely accomplished.

Every member of the Society for the Exploration of Unknown Regions was to accompany Flin to the Rocky Mountains. And when all the gentlemen had taken their seats Mr. Barnum shook hands with Flin and wished him God-speed. This was the signal for at least a hundred ladies to rush forward and shake the hand of the little man, and hundreds more would have done so had they not been ungallantly kept back by the police.

When all was ready, the train, which was decorated with flags, evergreens and flowers, commenced to move slowly out of the station, amidst the din of musketry, the playing of the bands, the hurrahing of the excited crowds, who were struggling frantically to get a last look at the hero of the day. Many of the ladies sobbed piteously, and as though their dear hearts would break. Then as one enthusiastic, wild shout of God-speed rose from thousands and thousands of voices, the train steamed away and was lost to view.

After a long and fatiguing journey the base of the mountain in which Avernus was situated was reached. Here a party of Indians and mules were engaged, and not without considerable difficulty the fish vessel, the stores and instruments were landed on the shore of the lake. Preparations were at once commenced for the descent into the unknown depths of the lake of mystery. The stores were put on board and packed away in the proper quarter. Then the air-producing reservoir was got into working order, and everything being ready, the adventurous Flin Flon commenced to bid adieu to his friends.

It was a strange, wild scene, and such a one as never before nor since disturbed the solitude of the awful place.

On the unruffled bosom of the dark waters was to be seem what might have been taken for a buoy, shaped like the tail half of a fish. From the tail floated the stars and stripes, and at the back was a small open door. On the shore were several small white tents, for the party had been there some days, while the final preparations were being made, and these tents contrasted strangely with the dark rocks, at the foot of which were gathered quite a little army of bald-headed and bespectacled savants, who talked in various languages, who chipped off pieces of rock with little hammers, and then delivered learned dissertations one to another upon the geological formation of the district, and the age of the various strata. They spoke of the "tertiary formation," of the "eocene," "miocene," and "pliocene." They said that geology was a subject upon which an autoschediastical judgment could not be pronounced. That the study of the "pocilite" would teach many truths with reference to the world's formation, and that amygdaloid was a book upon the pages of which the world's age was legibly written. They also touched upon the cylantheae and the cyclobranchiata, the gasteromycetes and the byssaceae[*], and likewise the zechstein[†]. With such simple and delightful words these old gentlemen made themselves understood, and thus were enabled to pass away the time pleasantly during the preparations for Flin's journey.

[* A family of lichens.]

[† Carbonate stone developed in the (late) upper "zechstein" division of the Permian in Europe.]

At length all was ready for a start, and when Flin had

shaken the hands of his friends, not a few of whom were affected

to tears, he stepped into a small boat and pulled a few yards out

to where the fish floated. Then by means of a ladder he mounted

to the doorway, and waving a farewell with his umbrella to the

spectators on the shore, he descended into the body of the

vessel, and having refreshed himself with a huge pinch of snuff,

he closed the door and proceeded to screw it up from the inside;

it fitted like the cap of a man-hole in a boiler.

It should be mentioned here that his travelling companions were six pigeons, a small goat, two fowls, six rabbits, a black cat, and a little white dog. These, with the exception of the cat and dog, were stowed in the tail.

When Flin had made the door water-tight he set his force-pump in motion, and commenced to take in his water ballast, and when the desired quantity had entered the tube the fish began to slowly sink.

It was a solemn moment was that. The onlookers began to ask themselves whether they had done right in allowing Flin to start upon such a strange journey. And that if his life were sacrificed would they not be accessory to his death? Not a few of them were really alarmed, and regretted that they had lent any serious hearing to the proposal of the expedition when first mentioned. But, in justice to them, it must be said that this feeling was very ephemeral. One of their number was risking his life in the noble cause of science, and even if he should never return they had no right to think ill of him, but should honour and respect his memory, and believe that he was actuated by the best and purest of intentions in setting out upon his adventurous journey.

The fish gradually went out of sight. First the dorsal fin was submerged, then the tail sank, until the glorious stars and stripes alone floated on the water.

It was the signal for a wild burst of cheering from the spectators, and the gloomy hollow reverberated with a thousand echoes, while far above, the eagles, startled by such an unusual noise, wheeled round and round and gazed down in bewilderment on the bald-headed intruders.

In a few minutes the flag itself was lost to view, and a large circle of air bubbles was all that was left to point out the spot where Flin's novel vessel had floated a little while before.

A small hut had been erected on the shore, and in this three men were to remain and keep watch for a fortnight. And as there was nothing more to do or nothing more to see the company turned their backs on Lake Avernus and hurried to their homes again, glad to get away from the gloomy and cheerless region.

FOR two hours after leaving the surface Flin continued to descend until the dial plate registered five hundred fathoms. As he noted this he felt a little proud as he thought that he was probably the first living human being who had ever attained such a depth. His ingenious invention was evidently a success. The reservoir was working capitally, and there was a plentiful supply of good air, and the only inconvenience that was experienced was an unusual degree of heat, the thermometer marking 82 degrees Fahrenheit, although the weather on land was extremely cold. The fish continued to descend until one thousand fathoms were marked, then bottom was touched lightly, and Flin instantly shifted the ballast and brought the fish into horizontal position. From his lookout windows he could see that he was on a shelving ledge of rock, and so connecting the crank of his paddle-wheels, he gave a few turns, and the machine glided further out and commenced to sink again. Very slowly now, owing to the horizontal position. When another hundred fathoms had been added to the depth, the fish again lodged on a ledge of rock, and instead of shelving, Flin could observe that it was quite flat and about five yards broad. Everything was satisfactory inside; the birds and animals were quietly sleeping, and the only sound to be heard was a strange, low humming noise. One peculiarity Flin noticed was, that the compasses were quite useless and magnetic attraction had ceased. As he was very tired, and the hour was late, he determined to let the vessel lodge where it was for the night, and having seen that everything was in working order, he went to bed, and was very soon enjoying a sound sleep, in spite of the novelty of his position. In all human probability he was the first mortal who, in the full enjoyment of perfect health and strength, had ever quietly reposed beneath the water at a depth of nearly two miles.

The night passed and morning came. Of course the only knowledge that Flin had that it was morning, was by looking at his chronometer watch, the hands of which indicated the hour of nine.

"Bless my life," cried Flin as he sprang out of bed, and regaled himself with a pinch of his precious snuff, "bless my life, how late it is. I declare I must have overslept myself."

Then having carefully adjusted his smalls and buttoned up his old green coat, he proceeded to attend to the creature comforts of his compagnons de voyage, and having noticed the state of the thermometer, which had risen in the night to 86 degrees, he made an entry in his diary to the effect that he had passed a very comfortable night eleven hundred fathoms below the surface of Lake Avernus. This task being completed he breakfasted right royally on a bottle of superb claret, some hard-boiled eggs, which had been prepared the day before, a few delicate slices of delicious ham, and finished off with a choice cut from a magnificent boar's head stuffed with truffles.

The next task was to get the craft off the ledge of rock, where it had securely lodged all night. Flin first of all made a careful survey of the position, as far as he was able, from his lookout windows. The electric lamps in the eyes illuminated the water for some distance, and he was enabled to see that on the left of him, and close to the vessel, rose a sheer wall of rock. And when his eyes became accustomed to the strange light he was astonished to observe that this wall was literally covered with some living things that could scarcely be called animals or fish. They had large, flat, round heads, and from each side of the head protruded an enormous eye. These eyes looked like balls of silver stuck on pins, and the creature was enabled to move them about in all directions. The bodies of these strange animals or fish were like thin pieces of pipe, about six inches in length, the tails of which were firmly attached to the rock. These things kept waving about with an undulating motion, and with a regularity that was monotonous.

"Good gracious!" cried Flin enthusiastically as he observed the extraordinary creatures, "what would I not give if I could only procure a few specimens. They are evidently an entirely new species of water animal, for I have never seen anything like them before. "

Longings, however, were vain, and so with that philosophical resignation which was part of his character he sat down and carefully entered in his diary an exact description (of which the above is a copy) of the extraordinary appearance of the living creatures; and as they partook more of the nature of reptiles than fish, he at once, with becoming modesty, classified them under the head of Reptilia Flonatin.

The entry finished, the great little man took snuff with a very self-satisfied air, and shipping the crank he set to work to impel the vessel into deep water. This was easily effected, for she rested very lightly on the rock, and being off she commenced to gradually sink again.

The peculiar humming noise which Flin had noticed on the previous evening now increased until it became like the combined buzzing of thousands of bees. It affected the drums of the ears, and produced a partial deafness. When the dial plate had registered another twenty fathoms a new and strange motion was imparted to the vessel. She went up and down like a see-saw plank, then she rolled, then described a half circle, bobbed up and down like a float, and finally commenced to spin round and round.

"Hullo!" cried Flin, as he seized his note- book and proceeded to jot down notes of the phenomenon, "this is suction. I'm going somewhere now."

Presently the humming noise increased until it became a perfect roar. The head of the fish vessel kept dipping violently, so that Flin was compelled to keep his seat. But with heroic composure he took snuff and calmly waited, pen in hand, for what might follow. He had not long to wait. The head made a plunge, until the vessel was almost perpendicular, and the little man was thrown to the floor. He gathered himself up, however, not the least disconcerted, and had just time to gain his seat when the vessel commenced to spin round violently like a newly-caught cockchafer on a pin. And all this time it was still sinking, sinking rapidly, and the roar was terrific. Any other man similarly situated would at once have given himself up for lost; but Flin did nothing of the kind. He managed to secure his precious snuff-box in the breast pocket of his coat, and then he firmly grasped with both hands the little table at which he was sitting, and which fortunately was screwed to the deck.

"Dear me!" he cried, gasping for breath, as a slight pause occurred in the rotary motion; "this is really very unpleasant, but it proves my theory correct that the lake is drained by a subterranean river and I am coming to the mouth of it."

He had scarcely given utterance to the words when again the vessel spun round, even more rapidly than before, and the noise was absolutely deafening, and rendered more distressing by the screams of the alarmed birds and animals imprisoned in the vessel with Flin.

In about twenty minutes' time the circular motion gave place to violent tossing, which, however, was less disagreeable than the other.

"Confound it!" he exclaimed. "In the interests of the honourable Society it is my privilege to represent I am prepared to encounter a great deal, but I must certainly enter a protest against being whirled round at the rate of fifty revolutions per minute."

Scarcely had the words left his mouth than the vessel commenced to rotate again, and Flin had not even time to clutch his snuff-box, which had been lying on the table, before it went flying away into a corner of the compartment. This distressed the little man sorely. The precious relic and its still more precious contents were as dear to him almost as his own life. But there was no help for it. He had to cling to the table like a leach, and his baldness in this instance was not without its advantages, for if his head had been covered with hair the probabilities are that the hair would have been whirled off.

Quite suddenly the motion changed, and swift as an arrow the vessel took a plunge down, then made a rush forward, and it became evident now that she was being carried rapidly along by a powerful current that was flowing through a tunnel.

For a time Flin was quite exhausted, and so giddy that he could see nothing. But he soon

recovered, and his first thought was for his gold box. This regained, he inspected his live stock. He found them all trembling violently and suffering great agitation. The thermometer registered 90 degrees, and the barometer was flying backwards and forwards in a most mysterious manner from "set fair" to "stormy." The pressure on the dial plate indicated a depth of water of not more than six fathoms.

"Hurrah!" cried Flin, as he noted this. "I am in the centre of the channel, and not far below the surface of the water."

He went to his lookout and peered into the water, but his vessel seemed to be standing still, though he knew from the speed indicator inside that she was travelling at the rate of quite twenty knots an hour.

After four hours of this rate the speed was reduced to about ten, and the fish was perfectly steady. Nothing was to be seen but the walls of water, rendered greenish by the electrical glow from the fish's eyes. Flin occupied himself with carefully writing up his diary and examining his instruments. He felt very well satisfied, for so far success had attended his venture, and the theory he had advanced at the meeting had now become actual fact, and he was sailing beneath the surface of a subterranean river. Not a single thought troubled him as to the future. He could live in his strange abode for a month, and long before that time the end of the river must be reached; and if he should come out in the centre of the ocean he would be able to rise to the surface, and either make for the nearest shore or be picked up by some passing ship, so he reasoned. But his enthusiasm never deserted him for a moment. He longed to realize his dream and become the discoverer of an internal world. The belief was firmly rooted in his mind that all subterranean rivers must flow to the centre of the earth, and it was evident that the one in which he was now travelling had a considerable fall, as proved by the rapidity of the current. He was a least two and a half miles from the surface of Lake Avernus, and was still descending lower. At anyrate, return was impossible, and wherever this river liked to take him to he must go, even though it should be to the infernal regions themselves.

About six o'clock, no change having taken place, he sat down to dine. The dinner was quite a recherché affair; boiled ham and delicious Indian pickles, boar's head and delicate French rolls and New Jersey butter, Catawba wine and calves'-foot jelly (specially prepared by an intimate lady friend), a morsel of Gruyère and a bottle of Moët.

Having fared thus sumptuously, Flin entered up his diary for the day, first noting that everything was going on all right. This task over he opened the escape valve for the foul air, and after that felt considerably refreshed, and, there being nothing more to do that night, he retired to rest.

He had slept about four hours when he was suddenly awakened by a violent shock, and for a moment the vessel seemed to be standing perfectly still, and there was a noise like the howling of a gale of wind through a long iron pipe. Flin sprang from his bunk. The vessel was trembling from head to tail, and the speed indicator was at "0." He realised the state of affairs in a minute. The fish had struck against a rock in mid channel. That this was the case was proved in a few minutes by the vessel swinging as the tide caught her and turned her violently round. Then with a dart and a plunge she rushed forward again, and the indicator registered twenty-two knots an hour.

Flin made a minute examination of the head of his fish, but could discover no damage beyond one of the electrical lamps in the eyes being displaced, but fortunately it was not broken.

"Confound it," he muttered, "that is a contingency I did not calculate upon, and a few such shocks would very soon bring my expedition to a premature close. It is no use meeting trouble halfway, though. I must hope for the best."

A very high rate of speed was now attained, and from a considerable depression at the head of the fish it was evident it was being carried down an inclined plane of water. Flin dressed himself hastily and took snuff thoughtfully.

"This is very awkward," he muttered, as he sat philosophically contemplating the indicator, which now marked thirty knots. "Exceedingly awkward," he continued. "We are evidently descending a rapid, and if anything should be in the way, well—"

He had not time to finish the sentence for the fish suddenly assumed a perpendicular position, the bold explorer was sent head over heels, and found himself lying against the partition beneath a heterogeneous collection of articles which had not been secured.

He lost no time in picking himself up and hurrying to the dial plate, which marked twenty fathoms, while the indicator had stopped.

"That's a pretty considerable waterfall, I guess," he remarked, as he groped for his snuff-box.

Presently the fish commenced to rise again from the depth of water into which the momentum had carried it, and as it did so it assumed the horizontal once more. Flin seized the lever which acted upon the ballast pipe, for he was determined to rise to the surface. He pressed the handle and the fish rapidly rose, but no sooner had it reached the top than it commenced spinning again at a bewildering rate. It had been caught in the eddy. Now it dived down as the water fell upon it. Then it rose again, spun round, rolled terrifically, bumped against the rocks, darted from side to side, was one moment perpendicular, the next horizontal, and all that Flin could do was to cling tenaciously to the table and wait.

At length there was a shock, and all motion, excepting an undulating one, ceased, but the roar of the water was perfectly deafening.

Flin scrambled to his portholes and looked out. The fish was on the top of the water, and jammed in a sort of cove formed by a jutting rock. It was perfectly still there, but a few yards further away the water was perfectly white with foam, and rushing along at an incredible speed.

"It won't do to stick here," thought Flin, "and I must get out into the stream somehow."

But how? That was the question that suggested itself to him. There was but one way, and that was to open the door and push the vessel out by means of a pole which had fortunately been placed on board. But then there were two risks to be run. The first was that of foul air, and the second was the danger of the fish being carried by the eddy beneath the waterfall and swamped before the cap could be closed again.

However, to stick there was to perish miserably and ingloriously, without any chance of his papers reaching the upper world. So of the two evils he chose the lesser, and getting out his tools he proceeded to unscrew the cap, and that being done, he very cautiously opened it the smallest possible bit. The noise that greeted him was beyond all description. It was as if a thousand ponderous machines were working one against the other. At the same time a blast of icy air rushed in, and in a few minutes the thermometer fell to six below zero.

Flin closed the cap, and hurrying to his berth, wrapped himself in a blanket. This done, he

returned to the door and gradually opened it, experiencing no other effect in doing so but that of extreme cold.

The luminosity of the foaming water enabled him, when his eyes became accustomed to the gloom, to faintly discern surrounding objects, and he discovered that he was in a spacious chamber. Before leaving New York he had provided himself with a large quantity of magnesium wire, and he now hastened to procure some of this. As he lighted it a scene burst upon his view that rendered him dumb with amazement.

It was an enormous cavern with a vaulted roof, from which hung brilliantly white festoons of stalactite. Behind, at some distance, was an unbroken fall of water of a least a hundred and twenty feet, and it was over this that Flin's fish had come. Above and below were gigantic pillars of stalactite and stalagmite, and some of the rock was covered with carbonate of lime, in which were embedded myriads of crystals that sparkled and flashed in the light with an inconceivably beautiful effect.

It was truly a subterranean world. The entrances to mammoth caves could be observed on all sides. There were what appeared to be flowers, and trees, and creepers, but they were all stone. The little bay in which the fish had been caught was the entrance to a cavern, and about a foot from the side of the vessel was the floor. Having first taken the precaution to secure the vessel by means of ropes, he provided himself with a plentiful supply of magnesium wire, and some peculiar torches that had been specially prepared for him in New York. Thus equipped he stepped out of the fish, and stood dry footed in that strange cavern, nearly three miles beneath the surface of the lake.

AS Flin stood up and contemplated the vastness of the chambers which surrounded him on all sides, he was struck with mingled feeling of awe and admiration. The strange solitudes where human being had never before entered were filled with wonders such as the upper earth could not compete with.

Before him rushed the river which might have been taken for the fabled Styx, and the gloomy caverns the abode of the grim ferryman, Charon.

To his right fell a gleaming sheet of water, and below it was a maelstrom, that made one giddy by its terrific gyrations. From the heights above Flin had tumbled into this mysterious spot, and all hope of ever returning to the upper world by the way he had come had vanished. But this thought gave the little man no uneasiness. He knew that the rushing river led somewhere, and wherever it led to he was willing to go.

He felt proud—as who would not have done so?—as he remembered that the invention, the child of his own brain, together with dauntless courage, had enabled him to penetrate thus far into those caverns of darkness.

The torches he had brought were about two feet long, and composed of a preparation of resin and pitch, firmly rammed into a metal case. Each torch was timed to burn from nine to twelve hours.

Lighting one of these he fixed it in the rock against which the fish was moored, so that it might serve as a guide on his return.

The effect of the light was inconceivably grand. Myriads of brilliant stars seemed to surround Flin. Above him was what appeared to be the blue vault of heaven, studded with the jewels of night, so that Flin could scarcely believe that he was far down in the bowels of the earth, and that above him were thousands and thousands of feet of solid earth and rock.

When he had gazed long on the marvellous sight, he slung two spare torches over his shoulder, and carrying a lighted one in his hand, he started into the interior of the cavern.

For some distance the way was along a narrow passage, from the roof of which depended the most magnificent stalactites that took almost every conceivable shape. Graceful festoons of flowers, delicate lace work, beautiful banners that seemed as if a passing breath of wind would set them waving-and long, graceful creepers that twined themselves round each in the most wonderful and complicated convolutions.

Presently the way broadened into an avenue, and then a little farther on there burst on the astonished gaze of Flin a sight that caused him to stand still with amazement.

Far as the eye could reach, on all sides, stretched an apparently limitless expanse of forest. Strange trees that had no counterpart on the upper earth, and which towered up until they were lost in the darkness. Their branches were interlocked, and their trunks were covered with parasites. But there was no delicate and harmonious blending of colour as in living nature. It was all white, broken here and there with streaks of brown. And over all was the stillness of death. Not a sound but the subdued roar of the waters, not a motion but the flickering torch.

It was a world of stone. Trees, branches, creepers, undergrowth; all were stone. Petrified into hard white rock, the result of countless thousands of years.

As the adventurous voyager stood there, gazing upon all this mystery and weirdness, he pictured the time when birds sang in the branches of the now stony trees, when balmy breezes rustled their leaves into pleasant music, and thousands of bright glad insects hummed their praises among the waving grasses and the nodding flowers. Flin knew that all these things must have been in far-off ages, until some incomprehensible convulsion of nature turned this part of the world upside down, and buried for ever out of sight this glorious forest. And now, after countless ages, perhaps millions of years, he had been permitted to penetrate into that stony forest that was steeped in the silence of death.

"It is grand, majestic, awful!" Flin exclaimed at last, unable longer to control his feelings.

Then he took snuff reflectively, and waving his torch aloft, its light was reflected in a million scintillating jewels, and a scene of dazzling loveliness met his astonished gaze.

Choosing one of the many paths which ran in all directions he travelled for some distance, until the cold was intense and the atmosphere heavy, so that breathing became laborious and difficult. The traveller thereupon determined to retrace his steps, for he was hungry and a little faint. But he very soon discovered, to his amazement and alarm, that he had missed his way, and the path by which he had come he could not find.

It was a terrible predicament, but Flin was not the man to stand still when action was necessary. So he travelled on rapidly for many miles through that world of stones, trees and herbs. Now he went north, then south. Then he tried east and west, but still he could not discover the friendly beacon which marked the spot where his fish vessel was moored.

It must be confessed that at this time a feeling of despair did weigh upon him, for the pangs of hunger were keen, and nature was exhausted. To have to die thus ingloriously, and when the success of his mission had seemed so probable, was calculated to depress even the strongest minded of men. But this feeling was very temporary. Flin drew out his beloved box, and refreshed himself with two large pinches of snuff. This gave him courage, and he once more started off, selecting a path that he fancied led in the right direction. Along this he travelled for some distance, until the trees grew less dense, and at last he stood upon the edge of a plain that was treeless and shrubless. He had come wrong again, that was certain, but the plain offered new temptations to his inquiring mind, and he was determined to gain all the knowledge he could.

He again had recourse to his snuff-box for refreshment, and he raised his torch aloft and gazed around. Behind was the forest, weird and spectral in its stony death, and before was what seemed to be a vast desert, dotted here and there with hillocks. He made his way to one of these hillocks and was astounded to find that it was composed of bones. Human bones, stone encrusted. And they had evidently belonged to a gigantic race of beings.

Flin collected several of these bones, and with a pocket measure, which he had thoughtfully provided himself with, he ascertained from very careful measurement that some of the bones must have belonged to men at least twelve feet high. This was an interesting discovery, and proved the truth of Biblical history, that there were giants on the earth in old days.

Flin counted no less than fifteen of these mementoes of an era that was completely lost in the mists of antiquity.

Further on he came to a stupendous mass of skeleton that with few exceptions was quite complete. It was that of a Behemoth, whose size would have dwarfed the largest hippopotamus that ever lived in African rivers. But it was all stone. Everything in the wonderful regions was stone.

Flin fixed his torch between two pieces of stone, and drawing forth his box, he took snuff very thoughtfully. Hunger and weariness were for the time forgotten, as he stood there, the only living thing in a dead world. There was something awe- inspiring in the very thought that he was gazing upon these interesting relics of such a far-off period.

"Ah," he muttered philosophically, "I wish my worthy fellows of the honourable Society for the Exploration of Unknown Regions could be aware that I am at the present moment looking upon a specimen of the anthracotherium, that evidently lived in the pre- historic age. It is clear, too, that the human inhabitants of the earth were in keeping with the huge animals that were contemporary with them. For here the skeletons show that there were a race of giants. It is strange now," he pursued reflectively, and examining the head of the monster at his feet very closely, "it is strange now, how these pachydermata and the human skeletons came to be together in this manner. It must have been due to some very sudden convulsions of nature, in which man and beast and forest were overwhelmed in the ruins that came upon them without any warning. What wonderful discoveries might be written upon these things to be sure! Dear me, I wish I could convey some of the specimens to Barnum's Museum, and that I might have the opportunity of reading a paper on the subject before my Society. True, one could only speculate as to how this forest came to be buried and subsequently turned to stone, but these skeletons are pages in the world's history that there is no misreading excepting by those who are wilfully blind. Ah, when I proposed this journey some persons were pleased to say that I was mad, but I would infinitely rather be mad, if madness consists in learning something of the wonders by which we are surrounded, than go through life scoffing and pooh-poohing at everything I don't happen to comprehend."

After he had travelled for over a mile another surprise awaited him in the shape of a river. Yes, another river of icy cold water, flowing silently and mysteriously between two banks of stony grass and shrubs, and carrying a cold current of air with it.

"My conscience, this is marvellous," cried Flin, in an ecstasy of delight. "How I should like to trace this river to its source. I feel as if I could devote my life to exploring the hidden mysteries of the wonderful subterranean forest. But that cannot be. I have a goal to press forward to, and I must reach it or perish. These unexpected marvels, however, serve to encourage me, and give me a stimulus if that were needed."

As the glare of the torch fell upon the stream, he noticed hundreds of queer-looking fish swimming about. They were unlike anything he had ever seen before. And one conspicuous peculiarity was that they had large white spots where the eyes would be in other fish.

"Ah, blind, totally blind," mutter Flin, as he noticed this, and stooping down he was enabled to examine the fish very minutely, as they were not at all alarmed by his presence. "Another sign of the great age of this forest," he continued, as he held his torch between his knees and made memoranda in his note book, "these fish have absolutely no eyes. Many ages of darkness must have passed to produce a family of eyeless fish; they evidently represent a species that have enjoyed the light of the sun at some period. If I mistake not, they belong to the order of megalichthys," he continued, as he rose from his stooping position. "Now, let me see, I think this river will show me the way I should go. By following down the stream I have no doubt I shall reach to place where my vessel is moored. I will put it to the test at anyrate."

He started on his journey once more, keeping close to the river, which ran almost straight. And at last he was cheered by seeing at a distance the welcome gleam of his signal torch. He hurried forward and found that the river he had followed flowed into the main one, lower down than the spot where he had started from. He found his fish vessel floating safely where he had moored her, and as soon as he got on board he began to prepare a substantial meal, for he was tired and hungry. And having fared sumptuously he wrote in his diary a full and detailed account of all the wonders he had seen.

By reference to his chronometer as soon as he returned, he found that he had been absent six hours and twenty minutes, during which time he estimated that he had travelled through the forest of stone a distance of twelve miles.

On examining his other instruments he was surprised to see that the inclination of the magnetic needle of his compass was extraordinarily great, and that for all practical purposes at present the compass was useless, as the needle was fixed. He thought possibly this was due to some magnetic attraction about the rocks in that part; and to test this he carried the instrument some distance into the forest, but without any result. The needle pointed downwards.

"Umph, very strange, very strange indeed," he muttered reflectively, as he returned to the vessel.

He was grieved to find on inspecting his stock that the pigeons and one rabbit were dead. So he cast their bodies out into the dark stream; and being satisfied that everything else was safe and in working order he retired for the night, with the roar of those subterranean waters ringing in his ears.

On the following day, much as he would have liked to have extended the exploration of these buried forests, he felt that it would not be policy to prolong his stay in the place, and so he made preparations for his departure, having first partaken of a very substantial breakfast.

His first care was to make a thorough examination of his craft; when to his dismay he discovered a large dent in the head, the result of the collision with the submerged rock. It did not admit the water, however, and in other respects the vessel was as sound as the day he started. Having satisfied himself on this point, he got all ready for continuing his journey. But here a new difficulty presented itself, and one that he had not calculated upon.