RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

"From Clue to Capture," Chatto and Windus, London, 1891

Headpiece from first edition.

IT was somewhere about the year 1820 that a poor and almost friendless youth, named Samuel Trelawney, found himself in Liverpool, with not even the proverbial sixpence in his pocket. Fortunately he attracted the notice of a gentleman engaged in the East India trade. This gentleman took such a fancy to Samuel that he offered to send him out to his house in Bombay, where he would receive a commercial training. This was the golden opportunity, and eagerly seized upon by the young man, who, after five years in the East Indies, returned to Liverpool owing to the death of his patron. But this time he was no longer a penniless youth. He had managed to scrape a little money together, and having acquired a thorough knowledge of commercial matters, he set up in business on his own account in a very small way. That was the beginning of the great concern that was to extend its ramifications to the four quarters of the globe.

Under Samuel's able guidance the business continued to grow, and he took in a partner—a Mr. Richard Lindmark. Soon the concern began to assume gigantic proportions, and the partners decided to turn it into a joint-stock company. Such a reputation had they gained that the required capital was subscribed three times over.

So much for the history of the firm of Trelawney, Lindmark, and Co. And it is necessary now that some reference should be made to the private history of Mr. Trelawney, who not only retained a very large financial interest in the company, but as managing director had almost the entire control of it.

At this period wonder was often expressed why Mr. Trelawney had never married. But there was a tender passage in his life that he carefully concealed from the vulgar gaze of the curious. He had had his little romance. The lady he loved was a light- headed, frivolous person who, knowing not the treasure she was throwing away, gave him up and bestowed her hand on a handsome but worthless Italian adventurer. There is not the slightest doubt that Mr. Trelawney had been passionately attached to the lady, and he felt the disappointment with a keenness that the world knew little of. But concealing his sorrow as best he could, he took his youngest sister Bertha as his housekeeper.

He had bought a charming estate on the Cheshire side of the Mersey, consisting of a mansion standing in about seven acres of grounds. It was known as the "Dingle," and here Mr. Trelawney and his sister Bertha dispensed lavish hospitality. Soon a mystery in connection with this place cropped up, and set the tongues of the gossips wagging. It was this. Into his house Mr. Trelawney received a boy child with a view to adopting it. Mr. Trelawney went from home one day, and after a week's absence he returned late one night, bringing the child, then about four years old, with him. The following morning he called all his household together in his library and said:

"Being a childless man, and never likely to marry, I intend to adopt this boy, who will be known to you as Jasper Trelawney. You will respect him as my son, for I shall be a father to him, as both his father and mother are dead."

This was all the explanation and information Mr. Trelawney condescended to give; and being so meagre, it simply aroused curiosity without in any way satisfying it.

The child was a dark-eyed, olive-skinned, curly-headed fellow, who speedily became a favourite. From boy to youth, from youth to young manhood every whim and wish of his was gratified by his over-indulgent foster parents—for Bertha Trelawney was no less attached to him than her brother was.

At his own earnest desire he had been taken into the business of Trelawney, Lindmark, and Co., and though he was not quite as steady and persevering as he might have been great hopes were formed of him.

But now the mystery that had begun when Jasper was brought as a child to the "Dingle" was increased by his sudden and unexplained disappearance. All that was allowed to leak out was this: A servant entered the library one morning suddenly not knowing that anyone was there, but to her amazement she saw Mr. Trelawney seated in a chair, though his face was bowed on the table as if he were overcome with some passion of grief. Grasped and crumpled in his left hand was a letter, and on her knees beside him, and weeping bitterly, her hands clasped on his shoulder, was his sister Bertha. The servant withdrew without disturbing them; but this scene had a strange significance when in the course of a day or two it became known that Jasper Trelawney had gone away.

On her knees beside him was his sister Bertha.

Twenty years went by, and Jasper Trelawney was entirely

forgotten by all, perhaps, save his foster parents. Bertha and

Mr. Trelawney were growing old, and he had become a silent,

reserved, and brooding man. Owing to enfeebled health he was now

only nominally the head of the great business which he had been

mainly instrumental in building up, but he was said to have

wealth almost beyond the dreams of avarice, and so great was the

faith of the world in him and his company, that capital to almost

any extent might have been obtained.

Fortunate was the man considered who held shares, or could obtain shares, in Trelawney, Lindmark, and Co. It can therefore be understood how those who were interested stood aghast, and how the commercial world was dumfoundered when one day, without any preliminary warning, it was announced that Trelawney, Lindmark, and Co. had failed for an enormous amount, and that everyone interested in the company would be utterly ruined. There was no limited liability then, and many a family, as they read the announcement of the failure, must have felt that misery and poverty stared them in the face. It was said that the assets were practically nil, while the liabilities were enormous. The great London firm of accountants—Rogers, Millbank, and Farmer—were appointed liquidators, and a few days later Mr. Rogers requested me to call upon him. He was a stern, hard-faced, practical man who seemed to ooze figures at every pore, and who had not one single atom of poetry or sentiment in his nature. He viewed the world, life, and all its associations through an atmosphere of arithmetic.

He informed me that enormous sums had been taken out of the business, and never accounted for, by some person unknown; that bogus bonds to a vast amount had been put upon the market, and, what was still more serious, that the register of the bond- holders had been stolen, so as to render it difficult, if not impossible, to detect the bogus bonds from the real ones. It was my task to trace the missing register and to find the thief. There was no suspicion, and no clue. The whole affair seemed an inexplicable mystery.

Having jotted down a few notes, and got all the details from him I could, I took my departure and began to plan out a course of action. From the high opinion in which Mr. Trelawney was held I felt that I could not do better than seek an interview with him at the outset, and I therefore lost no time in going down to the "Dingle."

The time of year was about the middle of October—chill

October. A cold wind was moaning over the land, which was sear

and brown; and the deep tints of decay dyed the foliage of the

trees. Although the coming winter was thus making itself felt,

the "Dingle" looked picturesque and beautiful. The grounds were

well wooded, and full of many surprises. There were rockeries,

arbours, bowers, and green retreats, where gurgled tiny

fountains; and through one portion of the estate flowed a stream

of deep water, which ultimately formed a miniature lake, on the

banks of which was a boat house. Ferns grew everywhere in

profusion, but they were drooping now to their winter death. I

noted that weeds had been allowed to spring up in the paths, as

if the master spirit of the place had ceased to interest himself

in it.

As I made my way up through the wooded grounds and crossed a leaf-strewn lawn in front of the house, I beheld an old, bowed, grey-headed man, dressed in a long coat and wide-awake hat. He was pacing to and fro on the gravel path by the main entrance to the house. His hands were clasped behind his back, and seemingly he was so absorbed that he did not notice me until I was close to him. Then he turned suddenly, and confronted me with an inquiring gaze. His face was pale and haggard, and bore evident traces of mental anguish.

"Mr. Trelawney, I presume?" I said, as I raised my hat.

"Alas! yes, I am Trelawney," he answered with a sigh. "Once the head of a great and wealthy commercial house; now a ruined, despairing, and broken man. But you are a stranger to me. Permit me to ask your name and business?"

"My name is Donovan. My business has reference to a painful matter in which I hope for your assistance."

"I am at your service," he answered, mournfully. "Pray, command me. But let us go into the house. It is cold and dreary here."

He led the way through the great hall to the library. A charming room, which—if I may use the expression—was redolent of literature. There were books from floor to ceiling; where books would not go were pictures, all perfect works of art; and where pictures could not be squeezed in there were elegant trifles, such as a man of refined taste loves to gather about him. The window commanded a view over a range of flower-beds to the stream beyond, which had for a background a dark wood, that was sombre with pines and cedars. Mr. Trelawney motioned me to an easy chair of the most ample proportions, delightfully cushioned; and, as I seated myself, he did the same in a similar chair beside the fire.

"I am here on behalf of the liquidators," I began, as he leaned back, folded his hands, and waited for me to speak.

"Yes," was the only answer he made; and it was uttered in a sort of dreamy way, as though his thoughts were not with what he said.

"You are aware," I proceeded, as I watched his face, which seemed to be absolutely expressionless at that moment—"you are aware that a very important book is missing?"

"Yes," he answered, again in the same dreamy way. "I heard it through Rogers, Millbank, and Farmer."

"But do you mean to say, Mr. Trelawney," I exclaimed, "that you did not know the register was missing until the liquidators made it known?"

He started into life at this. He sat up, with his long white hands nervously clutching the ends of the chair-arms; and his pale face lighted up with some inward passion that he was trying hard to conceal.

At this moment the door suddenly opened and a lady entered, but visibly started and drew back as she observed me, and looking at Mr. Trelawney she stammered:

"I—I—beg your pardon, but I didn't know you had anyone with you."

"This is a gentleman from London—Mr. Donovan," he exclaimed, as he sprang to his feet; and then, introducing her to me, he added: "My sister, sir, Miss Bertha Trelawney."

I bowed and she bowed. She was dressed in black; her white hair was neatly arranged beneath a cap; but her face, like her brother's, was pale and lined with thought and care. She seemed greatly agitated and suffering from nervous tremor and I was sure that she regarded me with mixed feelings of anxiety and fear. I watched her narrowly, and saw her exchange looks with her brother.

"Did you wish to speak to me?" asked her brother, apparently with the object of cutting short the interview.

"Yes," came the answer in low tones; and, asking me to excuse him for a few minutes, Mr. Trelawney and his sister went out of the room. In about ten minutes he returned, and he too seemed agitated.

"When my sister entered," he began as he resumed his seat, "I was about to tell you that the discovery of defalcations and the loss of the register is as much a revelation to me as it is to anyone. There is one thing I think that I may mention, and I do it with all reserve. But it is perhaps better that the information should come from me than from anyone else. About two years ago—it may be two and a half, I am not quite clear on the subject—I placed a gentleman in the concern as a confidential clerk. His name was David Brinsley. He was the son of an old friend of mine, who went out to Australia long ago, and died there. David, who had been partly brought up in the colonies, came to England after his father's death and sought me out. As he brought excellent testimonials, I had no hesitation in giving him a position of trust. Three months ago he was taken suddenly ill, and was dead in a few days. I remember now that it was immediately after David's death that I heard something about the register being missing."

"This is a remarkable story, Mr. Trelawney," I remarked, pointedly.

"Heaven forbid," he exclaimed, excitedly, "that I should cast aspersions on the character of a dead man; but I mention the incident for what it is worth. It is for you to make such inquiries as you think the matter deserves."

"Certainly," I answered, in a way intended to suggest that I did not think very much about the matter; but the truth was, I was morally certain I had got hold of the key to the mystery.

As I did not see that any object was to be served by my prolonging the interview then, I took my departure after a few casual questions bearing on the death of David Brinsley. As I left the steps and was crossing the lawn, I turned and looked at the house, and saw at the curtained window of a side room the deathly-white face of a woman, who seemed to be glaring at me. Directly she saw that she was observed, she dropped the curtain which she had been holding aside with her hand, and hurriedly withdrew. This trivial incident was not without its significance for me, and I began to weave out a theory as I pursued my way to Liverpool.

And one resolve I made was to look upon David Brinsley, alive or dead. Of course if, as Mr. Trelawney said, he was dead and buried, I could not see him alive. But, anyway, I wanted to see that he was as dead as he ought to be if he was really buried.

Necessarily there were certain legal formalities to comply with before my resolve could be put into practical shape. But certain information having been lodged, and all the forms of law been duly observed, an order was issued from the Home Office for the exhumation of the body of David Brinsley, who in the death certificate was described as a native of Australia; aged forty; and his decease was attributed to "pericardiac inflammation."

The disinterment took place at night after the cemetery gates were closed for the day. A small tent had been put up near the grave, and the oak coffin having been hoisted from the grave, was placed on trestles in the tent; and the undertaker's men proceeded to remove the lid and expose the face of the corpse, which proved to be in a remarkably good state of preservation. I had taken care to have several persons present who had been acquainted with David Brinsley, and as the lid of the coffin was taken off, I said collectively to these people as they crowded round:

"Look well at the face of that dead man, and tell me if it is David Brinsley's face."

"Look well at the face of that dead man,

and tell me if it is David Brinsley's face."

In reply to this question there arose a unanimous chorus of "Noes."

Perhaps I smiled a little to myself in spite of the "solemn presence of the dead," but a man may be pardoned for smiling, even under such circumstances, when he knows that he has achieved a triumph.

Although the plot had apparently thickened, I had picked up some important clues, and diligently set to work to follow them up. Remembering what took place between Mr. Trelawney and his sister on the occasion of my visit to the "Dingle," I felt certain that his secrets were her secrets, and believing, rightly or wrongly, that in her I should find more pliable material to work upon than in him, I decided to seek an interview with her in her brother's absence, and made my plans accordingly.

I went down to the "Dingle" one night, when, as I had previously ascertained would be the case, Mr. Trelawney was absent, and I sent word to Miss Trelawney that I desired to see her on a matter of urgent importance. She received me in the dining-room; a large, heavily-wainscotted and somewhat gloomy chamber, looking very ghostly on this occasion, for the fire had smouldered down to a handful of glowing ashes; and as a current of air that entered from some unseen aperture caused the flame of the large suspended lamp, by which the room was lighted, to flicker and flare, shadows moved to and fro, and chased each other over the table and up the walls, and dived and disappeared into recesses and corners, only to immediately reappear again. It was a chamber of shadows, weird and suggestive, and it brought to my mind the line:

"What shadows we are, and what shadows we pursue!"

As I stood dreaming dreams, a door at the end of the room opened, and Bertha Trelawney entered like a shadow, and we stood face to face. She seemed to me to have grown two or three years older, and she wore a look of ineffable mental suffering.

"You wish to see me?" she murmured, faintly.

"I do, madam," I answered, as I offered her a chair, into which she sank like a mechanical figure. "I am sorry to disturb you at this hour; sorry, too, to intrude upon your sorrow, for you have a sorrow, and a skeleton haunts you."

"What do you mean?" she asked, as she shuddered, sighed and looked nervously around the room.

"I must ask you another question by way of answer to yours," I said. "Did you know David Brinsley?"

"I have seen him," she replied, after some moments of hesitancy.

"Do you believe him to be dead?" The question startled her.

She rose to her feet suddenly; her eyes flashed, and her pale cheeks flushed a little. Pointing at me, and looking altogether as if she was some imperious ruler uttering a stern decree, she said hoarsely:

"Go! quit the house. I'll answer no more questions."

Bearing in mind that it is best to leave an angry woman, like a sleeping dog, alone; and as Miss Bertha Trelawney had so far played into my hands that I felt further questioning then would be supererogation, I bowed as gracefully as I could, and said:

"Certainly, madam, I will comply with your request," and bidding her good-night, which elicited no response, I withdrew; but I was conscious that I took forth from that chamber of shadows a link that would prove an important one in the chain I was patiently trying to piece together. The circumstances of the hour necessarily made me thoughtful, and almost unconsciously I found myself going down the leaf-strewn path beneath the avenue of trees that led to the lodge-gate, when suddenly I was aroused by the sound of someone approaching.

I immediately stepped off the path and amongst the trees, where I stood concealed. The approaching person proved to be Mr. Trelawney.

I followed with the intention of accosting him, but ere he had gone very far his sister met him. She had evidently been on the watch. She was without bonnet, but had wrapped a shawl around her head. She seized his arm eagerly, and I heard her say, in a tone pregnant with anxiety and grief:

"Oh, Samuel! I am so glad you have come. That dreadful man Donovan has been here, and it seems to me as if he had tugged at my very heartstrings and rifled my brain. I must not—dare not—see him again, for he makes me weak and powerless, when I should be strong and defiant."

"What do you mean?" demanded her brother, hotly.

What answer she made to this I know not, for they had passed beyond the radius of my hearing. Yet something—instinct or prescience, call it what you will—prompted me to linger about the house, as if in a vague and undefined way I expected the trees or the stones to make some revelation.

Presently a blaze of light suddenly appeared in an upper chamber. A white blind was drawn at the window, and on this blind the shadow of Mr. Trelawney was thrown, the outlines of his features being plainly visible. Then came another shadow—that of Miss Trelawney. The shadows blended, separated, formed fantastic pictures, and moved in a grotesque way, as shadows of living beings will when thrown on to a screen by a strong light.

Those pictures on the blind were riddles, and long I stayed trying to read them, until the light was extinguished and all was darkness there. I still lingered—still vaguely expecting a revelation—when the stillness of the night was broken by the harsh grating of the opening of a door. It was not the main door, but a side entrance. Concealing myself behind a clump of bushes, I watched and waited, and in a few minutes there came forth a man and woman, carrying what seemed a large box between them. As I recognized in that man and woman Mr. Trelawney and his sister, the movements of the shadow pictures I had seen on the blind were intelligible enough. The Trelawneys had been engaged up in that room packing something up. The something was in the box, and they were going to dispose of it. The box was heavy apparently, and they rested occasionally. As they moved off I followed cautiously. The revelation was coming at last. They went towards the stream of which I have spoken, and when they reached it they slid the box into the water; and I heard the gurgle and splash it made as it sank to the bottom.

Having given their secret into the safe keeping, as they supposed, of this dark stream, the Trelawneys returned to the house, and I went to the spot where the box had been thrown in, and noted the place by fixing a piece of stick in the bank. Then I hurried away, and obtained the assistance of a constable in plain clothes, and, provided with a boat-hook and a rope, I and my companion returned to the "Dingle" grounds. I easily discovered the marked spot on the banks of the stream, and in a short time we had fished up the box. We lost no time in conveying it to a house in the neighbourhood, where I temporarily rented rooms.

The box was an ordinary common deal wine case of the capacity of two dozen bottles, and the lid had been carefully screwed down, necessitating the use of a screw-driver to remove it. The hour was very late—long after midnight—but I had no idea of seeking rest until I learnt what the contents were of that case. Being a stranger in the house, I knew not where to look for a screw-driver. But, placing the box on the table, with two tallow candles on the mantelpiece to give light, my companion and I, by means of a broken-bladed table-knife, combined with infinite patience, managed to draw those screws, and thus release the lid. The box was lined with tin, and, inside, securely wrapped in an india-rubber sheet tied with string, was a parcel, which we proceeded to open with feverish eagerness; and, when the wrapping was removed, lo! the missing register of bond-holders was before us!

That "Dingle" stream, fatal to the hopes and desires of the Trelawneys, had thus revealed part, at least, of their secret; but there was still more to learn, though I never doubted for a moment that I should learn it in due course.

Having snatched a few brief hours of rest, I proceeded to London with the recovered register in my possession, and went at once to Mr. Rogers.

The sentiments which this hard-headed man of figures displayed were by no means in accord with my own feelings, but under the circumstances I had no alternative but to carry out his imperious mandate to arrest Samuel Trelawney without delay.

Two days later I was once more journeying down to the "Dingle," with the warrant for Trelawney's arrest in my pocket. It was late when I arrived at my destination, and the light of the short, bitter November day was fading away. On my inquiring for Mr. Trelawney I was shown into an ante-room, and presently Miss Trelawney came to me. I was struck by some change that was apparent in her. She was neatly dressed in black, and her white hair seemed to have become whiter. In her eyes was a look of infinite plaintiveness, and in her face from which the lines of anxiety and care seemed to have been smoothed away—was an expression that I can only indicate as that of divine resignation. She might, indeed, have sat as a model to some great painter for a picture of a Madonna. In a low voice, in which rang the music of sorrow, she said:

"I have been expecting your coming. You wish to see my brother?"

"I do, madam, for I have an unpleasant duty to perform."

She smiled sadly as she replied:

"If you will follow me I will take you to him."

She led the way across the hall, stopping for a moment at the table to light a tall wax candle that stood there in a silver candlestick, then proceeding, with silent footfalls, she went into the great dining-room—the chamber of shadows, as I have called it—and holding the candle above her head she approached the table, on which something was laid covered over with a sheet. She drew the sheet partly down, saying in her soft, low way: "Here is my brother, Mr. Donovan."

A solemn silence ensued as I gazed upon the dead face of Samuel Trelawney—a face that looked as if it had just been carved by some cunning sculptor to represent supreme tranquillity. Kindly death had smoothed away all the wrinkles, and had wreathed a faint smile about the lips, as if the weary man, with the eloquence of dead dumbness, was saying, "Behold, I sleep the eternal sleep, and the law's vengeance can smite me no more."

As I gently drew the sheet up again, over the marble-like figure, I turned to Miss Trelawney, who was apparently unmoved, and looked at her inquiringly for information. She walked towards the door, and I followed her back to the ante-room, where, sinking into a chair, she said:

"Since my dear brother has entered into his longed-for rest, there is no further necessity for concealment. He has fallen a sacrifice to his faithfulness and love for a worthless woman. Years and years ago he gave his heart to one who knew not how to appreciate it. She deceived him for the sake of a roué and gambler, whom she married. A few years of terrible bitterness; then, neglected and friendless, she lay on her death- bed. In her extremity she sent for my brother, to pray to him for his forgiveness. That was freely granted, and he vowed over her dead body that he would be a father to her orphan boy. Heaven knows how truly he kept that vow. But the boy had the seeds of wickedness within him so firmly rooted, that all the sweet and loving influences that were brought to bear proved of no avail, and he returned what was done for him with base ingratitude. But my poor brother was blind to all the lad's faults, and well-nigh broke his heart when he disappeared, leaving no trace behind him.

"Years afterwards he came back, a poverty-stricken, disgraced man. My brother listened kindly to his story of shame and wrong- doing, and on his promising reformation and for his dead mother's sake he forgave him, and under the name of David Brinsley placed him in a responsible position in the business. It was only to prove, however, the uselessness of scattering seed on barren soil. David Brinsley, the vagabond in heart, became a thief and forger, and the enormous sums out of which he cheated the business were squandered in gambling and dissipation. Yet, notwithstanding all this, my foolish brother said, 'He is the son of the woman I loved, and he must be saved.' I urged him with all the eloquence I could command to have him arrested, but his answer was: 'No; for his mother's sake, I will save him.'

"Brinsley at this time was living with some people who had a son much about his own age, and very like him in build. This son was taken ill, and, after being seen once by a doctor, died. The doctor gave a certificate, but he was told that the name of the deceased was David Brinsley. The parents of the dead man were heavily bribed by my misguided brother to allow this fraud to be perpetrated, and they removed immediately after the funeral, while David Brinsley lay in concealment here, but ultimately fled to Spain.

"In order to hide the extent of this wretched man's defalcations, my brother caused the register to be secretly removed from the office and brought here, but he could never bring himself to destroy it. He always said that some day it must be restored. From that moment his life became a terror to him. On the night that I so abruptly entered the room when you and Samuel were together, I was in a state of horrible distress, for I had just discovered that David Brinsley had gone out and nobody knew where he had gone to. He returned, however, at a very late hour; and subsequently I heard from a private source that you had caused the body of the supposed David Brinsley to be exhumed. I knew then that it was no longer possible to keep our fearful secret. I insisted on Brinsley leaving the house for ever, and, disguised as a clergyman, he went to Spain.

"After your last visit I urged my brother to return the register to the office, but he said he would not do that until he was assured that Brinsley was out of the reach of the law; though, yielding to my entreaties, he consented, with a view to its more effectual concealment, to hide it in the stream. The next morning we found it had been removed, and guessing that you had set a watch upon us, and fearing the dreadful exposure that would ensue, my dear brother's brain gave way, and, unable to endure the misery of his position any longer, he drowned himself in the stream which had failed to keep his secret.

"It is all over now; the sorrow, the suffering, and heart-ache are ended; and after the fitful fever of life, which for him ought to have been almost without a care had it not been for the deception of the woman he loved, he sleeps well. In a little while I shall join him, and realize that peace that the world cannot give."

Such was Miss Trelawney's sad story, which I proved to be

correct in every detail. And when I repeated it in substance to

Mr. Rogers, he growled and said:

"Ah! it is ten thousand pities that he has cheated the law."

As I have said, Mr. Rogers was an unsentimental man, and judged everything and everybody from his own matter-of-fact point of view. But I, while admitting that Mr. Trelawney was weak and foolish in a worldly sense, could hardly repress a sigh; and was tempted to say, "Judge not harshly, lest ye be judged harshly in return." Altogether it was a pathetic tale of a man's love, a woman's fickleness, and full of a great moral lesson which we who are not without some vein of sentiment may take to heart.

ONE morning a lady drove up in a hansom cab to my office and sought an interview with me. As she stated that her business was urgent she was at once shown into my room. She wore a thick veil, and as she seated herself on the chair I placed for her she threw this veil up and revealed a sweet, pensive face, that was marked with care and anxiety, however, while her eyes were red with weeping. She was a young woman with a fine and intelligent cast of features that betokened good birth and good breeding.

"I have come to you, Mr. Donovan," she began, "to enlist your services in a very painful case."

"I need scarcely say, madam, that I shall be glad to serve you if it is in my power to do so," I answered, feeling full of sympathy for her, even at that early stage of our acquaintance, for she appeared to be dreadfully distressed and to be suffering from some acute sorrow; and what man is there with a spark of chivalry in his nature who can withhold his sympathy from a pretty woman in trouble?

"It is a very painful case indeed," she continued as if she had not noticed my remark. Some sudden emotion overcame her, and she applied her handkerchief to her eyes to dry up the tears that would not be restrained. "I must take you into my confidence, she said in a fretting tone after a long pause."

"A confidence I shall respect," I remarked, "if I can conscientiously do so. But pray do not entrust me with your secrets unless you are quite sure I can be of use."

"Oh, I am sure you can," she exclaimed with a little passionate outburst, and stretching her hands towards me as if in appeal for protection and help. "If I had not thought so I should not have come here. Nor have I taken this step rashly or suddenly. It has cost me much thought and mental distress before I could make up my mind, for I shall have to disclose certain family secrets, and tell you a somewhat long and painful story, if it will not be trespassing on your patience too much."

"Before you proceed further, madam," I said, "permit me to ask if it is a case in which the power of the law is likely to be invoked?"

"Oh, yes," she answered quickly, "I am afraid it will."

"Pray go on, then. I am all ears.

"I may at once state," she continued, "that I have come here unknown to my relatives or friends, and on behalf of a very, very dear sister who would be furious if she knew I had come to you."

I looked at my visitor with quite a new interest as she made this remark, and I could not resist saying:

"May I be permitted to suggest, madam, that as you have come to me entirely on your own responsibility, and on somebody else's business——"

"I assure you it is my business," she put in with an eager quickness that betrayed the anxiety she was suffering from.

"I was going to suggest," I added, "that it might be advisable that you again revolved the matter in your own mind in order to be quite sure that you are justified in making me the repository of your family secrets."

"Mr. Donovan," she answered with a self-confidence and a stately dignity that at once made me feel that there was nothing frivolous about her, and that she had a mind of her own, "Mr. Donovan, I am fully alive to the responsibility I have assumed, and it is only after long and bitter mental suffering that I decided on this step. The business is serious, I assure you, and it affects the interests and wellbeing of one who is absolutely dearer to me than my own life. But may I tell my story in my own way?"

"Most certainly. I will not interrupt again unless I think it necessary."

"My name is Martha Tindall," she began. "I am the youngest daughter of the late General Tindall, who served the Honourable East India Company loyally and well for nearly forty years. My mother died when I was an infant, and my only sister—Lucy—and I were brought up by an aunt. Lucy is one of the most loving, amiable, and pure-minded women on the face of the earth. It may seem to you, perhaps, an exaggerated and sentimental view that I take when I say that my sister has always appeared to me somewhat in the character of a saint."

"You are much attached, then?" I remarked, as she paused again as her feelings once more overcame her.

"Attached!" she exclaimed. "I am sure there never were two sisters who were more devoted to each other than we were."

"You speak in the past sense, Miss Tindall," I observed.

"Yes; because since she married I do not think her affection for me is quite as strong as it was."

"She is married, then?"

"Yes, and that is what I am coming to. It is this marriage which has of late made my life almost a burden to me. My sister is nearly four years my senior. We were the only children of our parents, and for something like eight and twenty years we were scarcely ever separated from each other. I may at once state that our worldly circumstances were all that could be desired, for my dear father was enabled to leave us very comfortably off indeed, and soon after Lucy came of age she succeeded to her share of a fortune which was left to us by a bachelor uncle. I mention this because it has a strong bearing on what I have to tell you. The affection that we bore for each other was such that we made a vow we would never marry, as we could not bear the idea of separation. Indeed, to me the very thought of such a thing was almost unbearable. Now, beyond this attachment and dread of separation I don't know that we were different from any other women. We enjoyed life, we were fond of a certain amount of gaiety, and not averse even to a little adventure, travelling had a fascination for us, and we have been pretty well all over Europe.

"It is now just about five years ago that we were staying at Aix-les-Bains. My sister had been suffering from a slight attack of rheumatism, and she was advised to go through a course of the baths at Aix, hence the reason of our being there. To Aix I attribute all my unhappiness, and had we not gone to Aix I do not suppose I should have come to you to-day for your advice and assistance."

"Ah," I observed reflectively, "our lives after all, whatever may be said to the contrary, do seem to be governed by some immutable law of destiny, which we can no more avoid than we can perform the feat of flying."

"You mean we are not mere creatures of chance?"

"Yes."

"I think that is so," she answered. "At any rate, in my case it does really seem so.

"While at Aix we were introduced to a French gentleman, Count Eugène Rénoul, who endeavoured to make himself particularly fascinating. He was a young man, not more than three-and-twenty who seemed to be leading a fast and somewhat showy sort of life. He was fond of horses and gaiety, and being a Count and a handsome fellow to boot, he had any number of followers, and was looked upon generally as a man whose acquaintance was worth cultivating, and whom it was an honour to know. I confess, however, that he exercised no such influence over me. From the very moment I first saw him I took an instinctive dislike to him. If you were to ask me why I am sure I could not give you an answer. As I had no desire to appear conspicuous or disagreeable, I did all I could to conceal my feelings, particularly as my sister seemed to derive pleasure from his company. But, in a very short time, to my horror and disgust, he gave me to understand that he was desirous of paying his addresses to me. As soon as I became aware of that, I was at pains to make him clearly understand that if I allowed him to do so with any serious intention, I should not only be violating a vow which, rightly or wrongly, I could not but regard as a solemn one, but that I should be doing outrage to my own feelings, inasmuch as I was perfectly sure I could not reciprocate his sentiments. He laughed and said that, being a sanguine man, he should not be daunted by a first failure, and that he hoped in time to win my regard and love.

"This so alarmed me that I urged my sister to leave at once. But she raised an objection. She said that she was benefiting so much by her stay at Aix that she did not see why we should hurry away because a frivolous and light-headed young man chose to express admiration for me. This silenced me. How could I offer any opposition to my beloved sister's wishes? I was content to suffer and endure for her sake, and so I preserved an outward show of cheerfulness and contentment, though all the time a worm was gnawing at the bud and causing me intolerable anguish, for I could not close my eyes to the fact that all the time the Count was endeavouring in every possible way to impress me in his favour. For me to tell him that I did not like him, and never could like him, was of no avail; he simply laughed, and said that fortune favoured the brave and a faint heart never won a fair lady.

"Day after day I longed to hear him announce his intention of leaving, but he did not. And so the days stretched into weeks the weeks to months, and still he lingered. All this time he pressed his attentions on me, but I could not be blind to the fact that my sister was falling a victim to his spells of fascination. In other words she was in love with him, although she denied it when I taxed her with it, and said that he was amusing and that he did pour passer le temps; but beyond that she assured me that she hadn't a serious thought. My sister, I ought to say, could not boast of anything in the shape of good looks, for when she was a child she was the victim of an accident by which she was accidentally scalded on one side of the neck and face. It puckered and drew the skin to such an extent that to my way of thinking it was impossible to suppose any man could be attracted by her face."

"But some men," I ventured to suggest, "look at the beauty of the mind rather than the beauty of the person."

"A few, a very, very few men may," she answered, "but Count Eugène Rénoul cannot be numbered amongst that few. He gave me clearly to understand in many ways that it was not my sister he sought but me."

"He was at least a man of taste," I remarked, as I fixed my eyes on her own pretty face.

"Oh, sir," she exclaimed sadly, "pray do not pay me empty compliments. The business that has brought me here is far too serious for me to listen to them. But, to resume my narrative. The Count at last became so intolerable to me that I told my sister I should go out of my mind if she did not leave, and, seeing that I was really suffering, she consented at last to go. Oh, the relief that decision afforded me! and the day we turned our backs on Aix I prayed to the Lord that I might never again behold the Count. We travelled direct to England, and not until we had been some weeks in our comfortable London home did my wonted cheerfulness return. My dear sister used to twit me sometimes with having taken a stupid prejudice against the Count. And my answer was that some indefinable feeling seemed to warn me against him as a man who was too heartless, too selfish, too worldly, too frivolous to make any woman happy. However, in time his name was no longer mentioned. For myself I had all but forgotten him, and a year drifted away. Then one day I had been out alone on some shopping expedition, and, on my return home in the evening I found to my horror the Count and my sister sitting together. He saw my startled look, my discomfiture, and, rising, he greeted me with some warmth, saying that, being in London on business, he could not possibly resist the temptation to call and renew an acquaintance that had afforded him so much delight and pleasure.

"I left him no room to doubt that to me, at least, his presence was by no means welcome. Nevertheless he continued to call daily for some little time, when at last, to my relief, he announced that he intended to return to France the following day, and in bidding me adieu he said I was cruel, cold, and heartless, and that I had thrown a shadow over his life.

"Although I expressed regret that it was so, I attached no importance to his words, for I was convinced that he was a shallow man and utterly incapable of any sincerity of feeling. For the three months following his departure I was painfully conscious of the fact that my sister had changed in many ways. She seemed to have something on her mind, and when I pressed her to tell me what it was, she laughed, and accused me of being full of fancies. One night I could not resist taxing her with allowing her thoughts to dwell upon the Count, and I reminded her of her vow. For the first time in our lives she expressed anger with me, and said I was doing her an injustice. After that I resolved never to mention the subject again, for I thought it possible my surmises might be incorrect.

"Towards the end of that year Lucy announced to me that a mutual acquaintance—a lady living in Bournemouth—had invited her to spend a week or two with her. I was surprised that I had not been included in the invitation, as it was seldom indeed that my sister would go anywhere without me. However, I kept my thoughts to myself, and saw her off. Almost daily I received letters from her in which she assured me that the only thing lacking to render her happiness perfect was my presence. She was away a month. Then she returned home; and that night, as we were thinking of retiring, she drew an ottoman to my feet and sat down on it, and, resting her left hand on my knees, she said:

"'Martha, do you see that?'

"'What?' I asked.

"'That ring,' she answered, holding up her hand slightly, and for the first time I noticed that amongst other rings which she was in the habit of wearing there was a wedding ring, new and bright. My heart leapt into my mouth, and I know my face blanched as I gasped out, 'What does it mean, Lucy?'

"'It means,' she said, as she drooped her head 'that I am a wife.'

"'A wife?' I echoed, growing cold as if some terrible calamity had suddenly fallen upon me.

"'Yes,' she murmured.

"'Whose wife?' I asked.

"Then, bursting into tears, and hiding her face with her handkerchief, she sobbed:

"'Don't be angry with me, dear, but Count Eugène Rénoul pressed me to become his wife, and I could not resist him.'

"Oh, Mr. Donovan," exclaimed my visitor, as she, too, burst into tears, "you cannot form the slightest conception what I suffered when that announcement was made. It seemed as if my life had suddenly become a blank; as if something had been taken from me that would henceforth leave me lonely and broken hearted. My sister saw how deeply I was affected, and on her knees she implored me to forgive her. She told me that she had long secretly loved the Count. That on the occasion of his last visit to our house, when I refused him, he vowed to her that he did not care for me but loved her, and he asked her to become his wife. She consented. Her friend in Bournemouth was taken into their confidence, and arranged all the business. The marriage was celebrated in Bournemouth, and the Count had just returned to France to arrange some business matters there, and when he came back to England in the course of a fortnight, he and his newly- made wife were going to settle down in London.

"When I recovered from the shock the information caused me, I asked my sister if she had taken any steps to assure herself of the Count's position. Was he really all that he represented himself to be? She answered me that she had the most perfect confidence in him, and that he was a man of unsullied honour. What answer could I make to that? He was now my beloved sister's husband, and all I could do was to pray God to bless her union, and express a fervent hope that her life might be one of unsullied happiness.

"Two years have passed since that dreadful day, for dreadful indeed it was to me, and now I know that my sister's life is an utterly blighted one, and this man who threw his evil spell over her is not only breaking her heart but squandering her fortune. The only time I see her is when she comes to me, for her husband will not allow me to enter their house. She endeavours to hide her sorrow under an assumption of cheerfulness. But in appearance ten years have been added to her age. Her hair is whitening; and lines of anxiety and care are indelibly impressed on her dear face."

"It is a pitiable story," I said, as my visitor once more paused, overcome by her emotion, "but alas, it is by no means an uncommon one. Now what do you wish me to do?"

"To save my beloved sister from a premature grave."

"I do not quite understand you."

"This man is slowly but surely killing her. Yet she is as much fascinated with him as ever. She never breathes a word against him, notwithstanding that his scorn for her and his neglect are terrible."

"He is her husband," I remarked.

"True; and her curse."

"It is not an easy matter for an outsider to interfere between husband and wife."

"It is evident I have not made myself quite clear to you," she said. "This man married my sister for no other reason than to get her money. Now, what I want you to do is to find out his past history, and if possible convince my sister that he is unworthy of her esteem, for I am certain, perfectly certain, that his conduct is such as to justify proceedings being instituted for a divorce."

"But it is necessary that cruelty should also be proved," I reminded her.

"His cruelty is revolting," she cried. "Of course the difficulty is to get my sister to consent to proceedings being taken. She is infatuated, and it is only by showing him to be utterly worthless that this infatuation can be overcome."

I had listened with great interest to this narrative of shame and wrong, for given that what my visitor had told me was true, and even allowing for any exaggerations that her feelings might have led her into, it seemed highly probable that it was another case of misplaced confidence and shameless betrayal. Such things, of course, are common enough; indeed, they are of everyday occurrence, but that ought not to make us any the less anxious to redress the evil, to right the wronged, and punish the wrongdoer. Of course it often happens that the only punishment one can inflict is a public exposure, but as frequently as not that has no more effect than pouring water on the feathers of a living waterfowl. It was this view that led me to make the following remark to the unhappy lady, who seemed to be regarding me with painful anxiety as if hanging on the decision I should give.

"There is no doubt, Miss Tindall, from what you say, that your sister has been badly treated, but it is open to question in my mind whether it is a matter in which the law can interfere."

"Surely, sir," she cried, with anagonized expression, "the law can interfere to save a woman from being slowly done to death by a villain."

"It is a question how she is being done to death," I answered. "There is moral crime and legal crime, and the distinction between the two is very marked. For instance, a man marries a woman for the sake of her money. The woman is older than he is, and not personally attractive. He may neglect her; treat her with unkindness, and so blight her life by his conduct that she gradually pines away. Now, morally, that man would be guilty of her death; but it is hardly a case in which the law could interfere. I think in putting it this way I represent your sister's position."

"Oh, Mr. Donovan, do not dishearten me. You are my last hope. What I want you to do is to pluck the veil from this man's life, so that my sister's eyes may be opened. He has succeeded by some strange fascination in utterly subduing her to his will. She is weak, I know; the world may even call her a fool; but is that any reason why she should be crushed into her grave by this villain, whose stronger will takes hers captive, and leads her like a lamb to the slaughter? I tell you, sir, he is killing her. Her heart is slowly breaking; but she suffers in silence, while he wrongs her and dissipates her fortune. Now it is not her fortune I am thinking of. Let the man have it, so long as he will release my dear sister from his terrible spell, and restore her once more to me, for my life, like hers, is blighted."

The appeal that my visitor had so pathetically made to me I could not possibly be indifferent to, and so I promised her that I would see what I could do, and thus assured she took her leave.

The Count Eugène Rénoul occupied a house in the neighbourhood of Sloane Square, where he lived in considerable style, and I was soon in possession of information that made it clear he was a roué of a pronounced type. He was a handsome man, but bore in his face the traces of dissipation and fast living. His eyes were the most striking feature. In repose they were dreamy and languid, but under emotion or excitement flared up with a brightness that was truly remarkable. His eyes, indeed, gave the face a character and individuality that at once arrested attention. His wife, on the other hand, was something more than plain, with unmistakable indications of a weak will.

The Count's household, as I soon learnt, consisted of, besides himself and wife, a lady housekeeper—young and good looking—a butler, a footman, a cook, and four or five other female domestics, besides a coachman and groom. In this little domestic world the Countess was a cipher, a nonentity, and the lady housekeeper, Mrs. Florence Miller, ruled supreme.

So much came to my knowledge, and justified me, according to my way of thinking, in going much deeper into the Count's affairs. It would have been an insult to the most ordinary intelligence to ask anyone to believe that this man had married Miss Tindall for anything else but her money, and that, coupled with the way he treated her, stamped him as a man of a cowardly and treacherous nature.

In order to carry out my plan it was necessary to take the butler into my confidence. His name was Tonkins, and he had little or no regard for his master, and considerable sympathy for the unfortunate Countess. He readily consented to assist me. He introduced me into the house as his brother out of a situation, and obtained permission from Mrs. Miller for me to stay with him for a few days. I had not been many hours under that roof before I was made aware how thoroughly and absolutely the Countess was under the sway of her husband. But the power that he exercised over her was not of the ordinary kind. He swayed her by some powerful magnetic influence that seemed to deprive her of all power to act independently of his will. Her sister had said to me during the interview in my office, "He has succeeded by some strange fascination in utterly subduing her to his will." Herein Miss Tindall was right. The Count's wife was as potter's clay in his hands; he moulded and shaped her exactly as he wished.

On the third night of my stay in the house the butler informed me that a scene was taking place in the drawing-room between the Count and his wife; and I asked him at once if it was not possible for him to place me in such a position that I might be an ear and eye witness to what was going on. He said it was, for the drawing-room was a large one, and at one end was a conservatory filled with a collection of most beautiful plants. This conservatory could also be entered from the outside passage, and save when the Count had company it was never lighted up. So I was introduced silently into the conservatory, and I took my stand behind a large camellia tree that grew in a gigantic tub, and I was able from my coign of vantage to command a full view of the room. The Countess was sitting in a low chair near the fire and weeping bitterly, and her husband was pacing restlessly up and down, his hands thrust deeply into his pockets, his brows knit with a frown. Suddenly he stopped in his pacing, and exclaimed with brutal coarseness:

"You fool, stop your crocodile tears. Oh, how I hate you. Why don't you die, and relieve me of a burden."

With a moan of pain, and a movement wonderfully suggestive of a flutter like that of a wounded bird, she rose from her seat, fell on her knees at his feet, and, seizing his hand, pressed it to her lips, and said in a tone of poignant grief:

"Ah, Eugène, why do you treat me so cruelly. Is there anything I would not do for you? The very ground you walk on is precious to me——"

"Bah!" he hissed. "I am nauseated by your eternal simpering about the love you bear for me. There, get up and go to your room."

He waved his hand, and she rose, as it were, mechanically, looked at him with a look of such pleading sorrow that a heart less stony than his must have given way. But he bent his strange eyes upon her, and they seemed to me to gleam like the beady eyes of a snake; once more he waved his hand towards the door; and with a silent movement, a movement that was more like gliding than walking, she left the room, and a few minutes later Mrs. Florence Miller entered.

With a silent movement she left the room.

She was a little, fair-haired woman, with a doll-like face, just as pretty as a doll, but just as insipid. She had a pink and white complexion; blue eyes, and white, regular teeth that she fully revealed when she laughed. She literally ran over to him with a short, mincing step, and, throwing her arms round his neck, she said:

"She has been worrying you again, dear. Why do you allow her to do it? Really, it's a marvel to me that you have the patience with her that you have."

"It is no less a marvel to myself," he growled. "I wish the Lord would take her," he added; "she would be better in heaven than here."

"Yes. Poor boy!" said the fair-haired charmer as she patted his cheek. "But, never mind. Perhaps she will go soon. She is not made of cast iron, you know."

"No, but such creatures are not easily killed," he replied.

I did not wait to hear or see more. I had seen enough and heard enough to convince me that the Count was a villain, and the yellow-haired housekeeper a most dangerous woman, who in order to gratify her own selfish desires and aims would stick at nothing. Deception was written large in her waxy face; and in the depths of the soft blue eyes, as it seemed to me, there were indications that, like the purring cat, she could put forth cruel claws, and display a fierce nature if stroked the wrong way.

The next day I left the house, and that night went over to

Paris, for all my sympathies for the unhappy Countess were now

aroused, and I resolved to leave no stone unturned to save her,

if it were possible, from the machinations of her husband and

Mrs. Miller. My object in going to Paris was to learn something

of the Count's past history. I could not imagine that such a man

could have led a blameless life, and I have no doubt there were

many dark pages he fain would hide for ever from the light of

day. But it was my aim to place these pages before the world, if

that could be done, and by convincing the Countess of his perfidy

release her from his thrall.

At the very outset of my inquiries I ascertained that the Count was an adventurer of a very dangerous type. He had been many things in turn, and nothing long, and though he had managed to keep outside of the pale of the law it had only been by the skin of his teeth, as the saying is; for he had been mixed up in several very questionable undertakings; but by astuteness, good luck, or something else, he had contrived to escape the meshes of the legal net. The general opinion entertained about him was that he was an unmitigated scoundrel who, if he had had his deserts, would be a chained convict.

For three or four years, it was known, he had lived out of France before he went to England; and those years it was understood had been spent in Frankfort-on-the-Main principally, and so to Frankfort I made my way.

Within twenty-four hours of my arrival in that city I was in possession of the information that Count Eugène Rénoul had married a German lady who was possessed of a considerable fortune. He dissipated that fortune, then deserted her. Of these facts I got the most unmistakable documentary evidence, and armed with that hurried back to London, where I lost no time in seeking an interview with Miss Tindall.

I told her that I thought I was then in a position to say that I had succeeded in doing precisely what she wished me to do, namely, in getting such evidence of the villainy of Count Rénoul that her sister would repulse him, and release herself from his galling thraldom, as she could legally do since the Count had a wife living in Frankfort.

Miss Tindall rejoiced at this news, for it seemed to her to open up a way to a reunion between herself and her sister; and she undertook to have her sister there on a certain day that I might meet her and reveal to her the true character of the man she believed was her lawful husband. That interview duly took place, and anything more distressing I have not met in my experience. I began diplomatically and argumentatively, and endeavoured to show her that the Count had no true regard for her, and that his one aim was to obtain all her money, and that done he would fling her off.

She flashed up into fiery anger at this, and exclaimed: "Sir, I give you credit for good intentions, and acting as you are, no doubt, in concert with my sister, I will believe that you would not intentionally wound my feelings or make me unhappy, and yet you are doing both in speaking disrespectfully of my dear husband. Now, do not forget that he is my husband; and whatever his faults are they concern me alone, and not the outside world."

"You are wrong on both points, my dear lady," I answered. "Firstly, the Count's faults do concern the outside world; and secondly, in leading you to suppose that he is your husband he has shamefully and cruelly deceived you."

At this announcement she uttered a little cry. Then a look of scorn swept over her face as she said, with a sort of sneer:

"This is abominable, absolutely abominable. The Count is my husband, and I will hear no word spoken against him."

It was painfully evident now that the unhappy lady would not be easily convinced. I therefore had no alternative but to lay before her the documentary evidence I had secured of the Count's perfidy. Neither I nor her sister anticipated the result that ensued. She uttered a cry of pain; she placed her hand to her heart, staggered back, and fell on to a couch as if she had been shot. In a few moments, however, she sprang to her feet and said proudly:

"Yes, I see now that I have been deceived; but it is my own fault. I will accept the penalty."

"And what will you do, dear?" asked her sister anxiously.

"I don't know at present. I must think it over. At present my mind is all confused. This man whom I have called husband has been a dream to me. I have worshipped him, and it is very hard to believe that he has so cruelly wronged me."

As the scene was a very painful one I withdrew, feeling that I had no further business there at that juncture. Two or three days later I received a note from Miss Martha Tindall, who informed me that her sister was very ill indeed, and that she was gravely concerned about her. In less than a week after that came a second brief communication announcing the poor lady's death. If ever a woman died of a broken heart, through the perfidy of a villain, it was Miss Tindall. She had endured and suffered at his hands, and would have gone on enduring and suffering so long as she believed she was his true and lawful wife; but the terrible revelations that had to be made were too much for her. She had not sufficient strength of mind to rise to the occasion, and she could not endure the overwhelming sense of shame, wrong, and disappointment, and she drifted out into the dark and silent ocean, a victim to as base treachery as ever was put on record. She had, indeed, loved not wisely but too well.

When affairs came to be investigated, it was found that the

Count had had thousands of her money, and he had induced her to

make a will entirely in his favour. That will led to long

litigation, for it was fiercely contested by the unhappy lady's

relatives; and it was finally decided that, as it had been unduly

obtained by fraud, deception, and falsehood, it could not be held

valid. All this might have been decided by common-sense men in

five minutes, and months and months of a solemn farce would thus

have been avoided; but then the legal vultures were not likely to

let such a good picking escape them, and they swooped and mangled

the remains until all that was left for the triumphant relatives

were the mouldy bones. Costs, of course, were given against the

Count, but as well might they have been given against the man in

the moon.

The rascal took good care to make himself non est when wanted, but there was a certain poetic justice in the fact that a few months later he was arrested in Baden-Baden for swindling an hotel-keeper, and was sentenced to a term of imprisonment.

Miss Martha Tindall only survived her sister a year. The bond that had bound them had been too powerful for one to live alone, and Martha's grief for the loss of her other half cankered her life away, and she joined her sister in that better land where the wicked cease from troubling and the weary are at rest.

BUSILY engaged one morning in my office in trying to solve some knotty problems that called for my earnest attention, I was suddenly disturbed by a knock at the door, and, in answer to my "Come in!" one of my assistants entered, although I had given strict orders that I was not to be disturbed for two hours.

"Excuse me, sir," said my man, "but a gentleman wishes to see you, and will take no denial."

"I thought I told you not to disturb me under any circumstances," I replied somewhat tartly.

"Yes, so you did. But the gentleman insists upon seeing you. He says his business is most urgent."

"Who is he?"

"Here is his card, sir."

I glanced at the card the assistant handed to me. It bore the name:

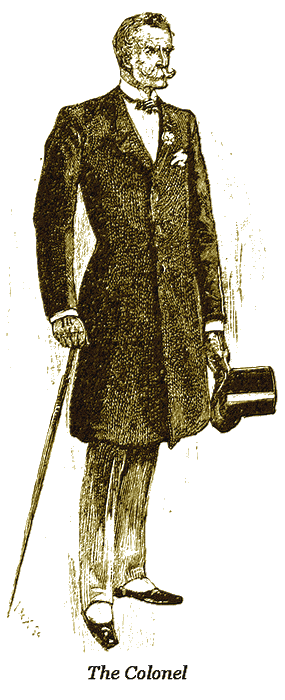

COLONEL MAURICE ODELL

THE STAR AND GARTER CLUB

Colonel Maurice Odell was an utter stranger to me. I had never

heard his name before; but I knew that the Star and Garter Club

was a club of the highest rank, and that its members were men of

position and eminence. I therefore considered it probable that

the Colonel's business was likely, as he said, to be urgent, and

I told my assistant to show him in.

A few minutes later the door opened, and there entered a tall, thin, wiry-looking man, with an unmistakable military bearing. His face, clean shaved save for a heavy grey moustache, was tanned with exposure to sun and rain. His hair, which was cropped close, was iron grey, as were his eyebrows, and as they were very bushy, and there were two deep vertical furrows between the eyes, he had the appearance of being a stern, determined, unyielding man. And as I glanced at his well-marked face, with its powerful jaw, I came to the conclusion that he was a martinet of the old- fashioned type, who, in the name of discipline, could perpetrate almost any cruelty; and yet, on the other hand, when not under military influence, was capable of the most generous acts and deeds. He was faultlessly dressed, from his patent leather boots to his canary-coloured kid gloves. But though, judging from his dress, he was somewhat of a coxcomb, a glance at the hard, stern features and the keen, deep-set grey eyes, was sufficient to dispel any idea that he was a mere carpet soldier.

"Pardon me for intruding upon you, Mr. Donovan," he said, bowing stiffly and formally, "but I wish to consult you about a very important matter, and, as I leave for Egypt to-morrow, I have very little time at my disposal."

"I am at your service, Colonel," I replied, as I pointed to a seat, and began to feel a deep interest in the man, for there was an individuality about him that stamped him at once as a somewhat remarkable person. His voice was in keeping with his looks. It was firm, decisive, and full of volume, and attracted one by its resonance. I felt at once that such a man was not likely to give himself much concern about trifles, and, therefore, the business he had come about must be of considerable importance. So, pushing the papers I had been engaged upon on one side, I turned my revolving chair so that I might face him and have my back to the light, and telling him that I was prepared to listen to anything he had to say, I half closed my eyes, and began to make a study of him.

"I will be as brief as possible," he began, as he placed his highly polished hat and his umbrella on the table. "I am a military man, and have spent much of my time in India, but two years ago I returned home, and took up my residence at the Manor, Esher. Twice since I went to live there the place has been robbed in a somewhat mysterious manner. The first occasion was a little over a year ago, when a number of antique silver cups were stolen. The Scotland Yard authorities endeavoured to trace the thieves, but failed."

"I think I remember hearing something about that robbery," I remarked, as I tried to recall the details. "But in what way was it a mysterious one?"

"Because it was impossible to determine how the thieves gained access to the house. The place had not been broken into."

"How about your servants?" I asked.

"Oh, I haven't a servant who isn't honesty itself."

"Pray proceed. What about the second robbery?"

"That is what I have come to you about. It is a very serious business indeed, and has been carried out in the mysterious way that characterized the first one."

"You mean it is serious as regards the value of the property stolen?"

"In one sense, yes; but it is something more than that. During my stay in India I rendered very considerable service indeed to the Rajah of Mooltan, a man of great wealth. Before I left India he presented me with a souvenir of a very extraordinary character. It was nothing more nor less than the skull of one of his ancestors."

As it seemed to me a somewhat frivolous matter for the Colonel to take up my time because he had lost the mouldy old skull of a dead and gone Rajah, I said, "Excuse me, Colonel, but you can hardly expect me to devote my energies to tracing this somewhat gruesome souvenir of yours, which probably the thief will hasten to bury as speedily as possible, unless he happens to be of a very morbid turn of mind."

"You are a little premature," said the Colonel, with a suspicion of sternness. "That skull has been valued at upwards of twelve thousand pounds."

"Twelve thousand pounds!" I echoed, as my interest in my visitor deepened.

"Yes, sir; twelve thousand pounds. It is fashioned into a drinking goblet, bound with solid gold bands, and encrusted with precious stones. In the bottom of the goblet, inside, is a diamond of the purest water, and which alone is said to be worth two thousand pounds. Now, quite apart from the intrinsic value of this relic, it has associations for me which are beyond price, and further than that, my friend the Rajah told me that if ever I parted with it, or it was stolen, ill fortune would ever afterwards pursue me. Now, Mr. Donovan, I am not a superstitious man, but I confess that in this instance I am weak enough to believe that the Rajah's words will come true, and that some strange calamity will befall either me or mine."

"Without attaching any importance to that," I answered, "I confess that it is a serious business, and I will do what I can to recover this extraordinary goblet. But you say you leave for Egypt to-morrow?"

"Yes. I am going out on a Government commission, and shall probably be absent six months."

"Then I had better travel down to Esher with you at once, as I like to start at the fountain-head in such matters."

The Colonel was most anxious that I should do this, and, requesting him to wait for a few minutes, I retired to my inner sanctum, and when I reappeared it was in the character of a venerable parson, with flowing grey hair, spectacles, and the orthodox white choker. My visitor did not recognize me until I spoke, and then he requested to know why I had transformed myself in such a manner.

I told him I had a particular reason for it, but felt it was advisable not to reveal the reason then, and I enjoined on him the necessity of supporting me in the character I had assumed, for I considered it important that none of his household should know that I was a detective. I begged that he would introduce me as the Rev. John Marshall, from the Midland Counties. He promised to do this, and we took the next train down to Esher.

The Manor was a quaint old mansion, and dated back to the commencement of Queen Elizabeth's reign. The Colonel had bought the property, and being somewhat of an antiquarian, he had allowed it to remain in its original state, so far as the actual building was concerned. But he had had it done up inside a little, and furnished in great taste in the Elizabethan style, and instead of the walls being papered they were hung with tapestry.

I found that besides the goblet some antique rings and a few pieces of gold and silver had been carried off. But these things were of comparatively small value, and the Colonel's great concern was about the lost skull, which had been kept under a glass shade in what he called his "Treasure Chamber."

It was a small room, lighted by an oriel window. The walls were wainscotted half way up, and the upper part was hung with tapestry. In this room there was a most extraordinary and miscellaneous collection of things, including all kinds of Indian weapons; elephant trappings; specimens of clothing as worn by the Indian nobility; jewellery, including rings, bracelets, anklets; in fact, it was a veritable museum of very great interest and value.

The Colonel assured me that the door of this room was always kept locked, and the key was never out of his possession. The lower part of the chimney of the old-fashioned fireplace I noticed was protected by iron bars let into the masonry, so that the thief, I was sure, did not come in at the window, for it only opened at each side, and the apertures were so small that a child could not have squeezed through. Having noted these things, I hinted to the Colonel that the thief had probably gained access to the room by means of a duplicate key. But he hastened to assure me that the lock was of singular construction, having been specially made. There were only two keys to it. One he always carried about with him, the other he kept in a secret drawer in an old escritoire in his library, and he was convinced that nobody knew of its existence. He explained the working of the lock, and also showed me the key, which was the most remarkable key I ever saw; and, after examining the lock, I came to the conclusion that it could not be opened by any means apart from the special key. Nevertheless the thief had succeeded in getting into the room. How did he manage it? That was the problem I had to solve, and that done I felt that I should be able to get a clue to the robber. I told the Colonel that before leaving the house I should like to see every member of his household, and he said I should be able to see the major portion of them at luncheon, which he invited me to partake of.

I found that his family consisted of his wife—an Anglo- Indian lady—three charming daughters, his eldest son, Ronald Odell, a young man about four-and-twenty, and a younger son, a youth of twelve. The family were waited upon at table by two parlour-maids, the butler, and a page-boy. The butler was an elderly, sedate, gentlemanly-looking man, the boy had an open, frank face, and the same remark applied to the two girls. As I studied them I saw nothing calculated to raise my suspicions in any way. Indeed, I felt instinctively that I could safely pledge myself for their honesty.

When the luncheon was over the Colonel produced cigars, and the ladies and the youngest boy having retired, the host, his son Ronald and I ensconced ourselves in comfortable chairs, and proceeded to smoke. Ronald Odell was a most extraordinary looking young fellow. He had been born and brought up in India, and seemed to suffer from an unconquerable lassitude that gave him a lifeless, insipid appearance. He was very dark, with dreamy, languid eyes, and an expressionless face of a peculiar sallowness. He was tall and thin, with hands that were most noticeable, owing to the length, flexibility and thinness of the fingers. He sat in the chair with his body huddled up as it were; his long legs stretched straight out before him; his pointed chin resting on his chest, while he seemed to smoke his cigar as if unconscious of what he was doing.

It was natural that the robbery should form a topic of conversation as we smoked and sipped some excellent claret, and at last I turned to the Colonel, and said:

"It seems to me that there is a certain mystery about this robbery which is very puzzling. But, now, don't you think it's probable that somebody living under your roof holds the key to the mystery?"

"God bless my life, no!" answered the Colonel, with emphatic earnestness. "I haven't a servant in the house but that I would trust with my life!"

"What is your view of the case, Mr. Ronald?" I said, turning to the son.

Without raising his head, he answered in a lisping, drawling, dreamy way:

"It's a queer business; and I don't think the governor will ever get his skull back."

"I hope you will prove incorrect in that," I said. "My impression is that, if the Colonel puts the matter into the hands of some clever detective, the mystery will be solved."

"No," drawled the young fellow, "there isn't a detective fellow in London capable of finding out how that skull was stolen, and where it has been taken to. Not even Dick Donovan, who is said to have no rival in his line."

I think my face coloured a little as he unwittingly paid me this compliment. Though my character for the nonce was that of a clergyman I did not enter into any argument with him; but merely remarked that I thought he was wrong. At any rate, I hoped so, for his father's sake.

Master Ronald made no further remark, but remained silent for some time, and seemingly so absorbed in his own reflections that he took no notice of the conversation carried on by me and his father; and presently, having finished his cigar, he rose, stretched his long, flexible body, and without a word left the room.

"You mustn't take any notice of my son," said the Colonel, apologetically. "He is very queer in his manners, for he is constitutionally weak, and has peculiar ideas about things in general. He dislikes clergymen, for one thing, and that is the reason, no doubt, why he has been so boorish towards you. For, of course, he is deceived by your garb, as all in the house are, excepting myself and my wife. I felt it advisable to tell her who you are, in order to prevent her asking you any awkward questions that you might not be prepared to answer."

I smiled as I told him I had made a study of the various characters I was called upon to assume in pursuit of my calling, and that I was generally able to talk the character as well as to dress it. A little later he conducted me downstairs, in order that I might see the rest of the servants, consisting of a most amiable cook, whose duties appeared to agree with her remarkably well, and three other women, including a scullery-maid; while in connection with the stables were a coachman, a groom, and a boy.

Having thus passed the household in review, as it were, I next requested that I might be allowed to spend a quarter of an hour or so alone in the room from whence the skull and other things had been stolen. Whilst in the room with the Colonel I had formed an opinion which I felt it desirable to keep to myself, and my object in asking to visit the room alone was to put this opinion to the test.