RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

"Found and Fettered," Hutchinson and Co., London, 1894

IT is not inapropos for me to preface the remarkable story I have to tell by stating that, speaking in a general way, I am not in sympathy with things Russian. In spite of what may be said to the contrary by those who have an interest in misrepresenting facts, there is pretty conclusive evidence that the great and unwieldy Russian nation has in many respects scarcely emerged from mediaeval barbarism. It is impossible for any free-minded person to travel through Russia at the present day without being made painfully aware of this. It might very aptly and somewhat epigrammatically be said that every man in Russia who rules is a tyrant, and every man who does not rule is a slave. Freedom, as we understand it, is unknown in the dominions of the Czar. The press is muzzled, the mouths of public speakers are muzzled, and if a Russian or a foreigner dwelling in Russia holds views that are adverse to the ruling powers, let him not express them if he values his liberty, his happiness, his life. The stranger travelling in the country is liable to be pounced down upon at any moment by some Government myrmidon, who, in his narrow-mindedness, thinks he sees an enemy in him. And woe betide the man who gets within the clutches of the law. Under some frivolous pretext or another he may be detained without trial and without examination, until he moulders and his heart rends in twain with unbearable despair, suspense, and hope deferred.

The Russian form of government is as despotical as it is obsolete, while those entrusted with its administration are not as a rule men distinguished by marked ability or enlightenment, but they are those who have friends at Court, and who have given evidence of being haters of the people. In no other country in the world can you find people sunk in such besotted ignorance as are the masses of Russia. Foreign literature of all kinds is absolutely unknown to them, while such native papers as may come into their hands are written through Russian spectacles, and with the fear—which is almost greater than that of death—of the Government censor. Hundreds of persons are at the present moment languishing in Siberia for no other reason than that in some unguarded moment they allowed their feelings to betray them into a too free expression of opinion. Then followed the inevitable result. They were arrested, accused of being "dangerous to the State," subjected in some cases to a trial that was all a farce, but as often as not there was no trial at all. They were then kept in some dreadful prison for periods ranging from months to years, and finally had to march with chained gangs into Siberia. To the world generally all this is a matter of tradition, if not of history, but to those who have travelled in the country with open eyes and unshackled minds it is more than tradition; it is a pitiable, a hideous truth.

Although I have thus freely expressed my opinion on the Government of Russia, let it not be supposed for a single moment that I countenance in any way the methods adopted by the revolutionary societies in their efforts to redress their wrongs. Tyranny cannot be arrested by still greater tyranny, while the wild justice of revenge can in the end only serve to bring disaster on the heads of the weaker party. Yet, if ever political crimes can find justification in shameless oppression, they can do so in Russia; and in Treskin's case this was particularly so. The agitation that was caused in England at the time Treskin was arrested in London through my instrumentality will not be forgotten by those whose memories can carry them back for a generation. I venture to think, however, that it will add to the interest of my story, if I relate it in all its detail, from the very beginning to the pitiless end.

Some time before the Crimean War a young Pole by birth, named Egór Treskin, was living in St. Petersburg; he was employed as a clerk in a bank, and being very studious, and very industrious, he devoted his spare time to teaching languages in one of the public schools. In this capacity he met a young lady, who was destined to become his wife. She was a Russian, and an orphan. Her father had held a Government appointment as an inspector of mines, and in that capacity had ample opportunity of seeing the iniquity of the Russian exile system. Moved to deep pity and sympathy by what came under his notice, he allowed his feelings to get the better of his discretion, and his complaints of the tyranny and cruelty that were practised by governors, managers, overseers, and others, were many The result being he incurred the hatred of this class of people, and became a marked man. Revenge was not long in following. He was denounced as a conspirator. By some means he was lured to a house of a well-known political suspect, who was under surveillance. The man was then accused of having visited this house. He could not deny it, and was at once arrested. In this country such a thing would be laughed at, for here you may spout treason and act treason to your heart's content, and nobody will take any notice of you. But in Russia it is different; only let the faintest whisper of treason be breathed against a man in that benighted land, and the chances are it seals his doom.

In this unfortunate fellow's case, he had too many political and other enemies for him to hope to escape from the effects of the accusation. The more he tried to explain, the more deeply did he seem to become involved. He was like a bird which once gets the ensnaring lime upon its wings. All its efforts to free itself from the tenacious substance are futile, and serve but to exhaust it. So in Russia with a man who is suspected of treason. Hope has gone for him. He can never be the same again. In the case I am citing the man was detained, first in one prison and then in another, for five years, and, having been financially and socially ruined, he was transported to Siberia, leaving a delicate wife behind, and three young children—two sons and a daughter, Catherine. The mother, soon after the departure of her husband, died, and the children were brought up by a relative. Three years later the father was shot in attempting to escape from his place of exile.

When Egór Treskin first made Catherine's acquaintance, she was about twenty and very beautiful. Her father, however, having been a political prisoner, his children were subjected to a shameful system of espionage. Catherine, in particular, had suffered great annoyance, but she resolved to live it down, and was desirous of qualifying herself for a teacher. Treskin fell in love with her, and as soon as that was known, he was secretly warned that she was a member of a tainted family, therefore must be tainted herself. This was infamous, but, unhappily, it is common in Russia. Although Treskin knew, no doubt, the seriousness of the warning, he allowed love to prevail, and married Catherine. The first year or two of their married life would seem to have been happy enough. A child was born to them and there was nothing apparently to disturb their serenity. But the ways of the Russian Government are inscrutable and mysterious, like those of the "Heathen Chinee." One day, during Treskin's absence at his business, two police officers entered his house, and arrested his wife, on the baseless and shameless charge of conspiring against the State. When the husband returned he found that his wife had been dragged off, with her helpless infant, to some prison. Distracted, he flew to headquarters, and begged to know, firstly, of what his wife was accused; secondly, where she had been taken to; thirdly, he craved to be allowed to see her. With the brutal cynicism so characteristic of the Russian official, he was told that he had better go away and hold his tongue, lest he himself should be placed under arrest. It was hinted that he had chosen to marry a suspected woman in spite of warning given to him, and he must therefore abide by the consequences.

For two long, dark, dreary, and dismal years Treskin moved heaven and earth in his endeavours to try and see his wife and child, but without effect, until at last it was intimated to him that she was to be exiled to Siberia. Broken-hearted and almost mad with grief, he vowed that he would accompany her. At last, with a diabolical refinement of cruelty, he was allowed to see her as she was on the eve of departure for the far east of Siberia. She had grown haggard and old with suffering. Her baby was dead, and it was only too evident her mind was unhinged.

Treskin applied for and obtained permission to accompany his unhappy wife, and they travelled together for many dreadful months, suffering the horrors of the steppes, and the hardships and privations of the dreadful journey. Poor Catherine's strength was unequal to the strain, and somewhere in the Trans-Baikal provinces she was stricken with mortal illness, and on her deathbed she told her husband a revolting and fearsome story in which a high Russian official, Count Cherékof, who was an inspector of prisons, was implicated. She said that she had intended to keep the shame and suffering she had endured a secret, but felt that she could not die until she had revealed it to her husband.

Over his dead and outraged wife's body Treskin swore an oath to God that he would be revenged, and having buried her in a convict's grave he set his face westward again, brooding deeply over his shame and wrong. In due time he found himself once again in St. Petersburg, but he was so changed that his most intimate friends failed to recognize him. Secretly and silently he allied himself with the enemies of the Government and became one of the most dangerous of conspirators, most pronounced of Nihilists. His wrongs had turned his heart to stone and he was pitiless, terrible, and deadly.

I cannot follow his career in all its details during the three succeeding years after his return from Siberia, but it may be summarized as one of arch plotting against the Government and the institutions of his country. There is no doubt his wrongs and shame had made him a dangerous and insidious enemy, and it is certainly remarkable that during this period he managed to elude vigilance and escape suspicion.

It would seem that during all this time he never forgot his enemy, but no opportunity occurred for him to carry out his deadly act of vengeance. Count Cherékof had been sent on some secret mission to France and England. But Treskin evidently knew how to wait. He bided his time, and his time came at last. The Count returned to Russia, and for some reason or other was soon after entertained at a public banquet. That night late a note was slipped into the Count's hand as he was in the act of leaving the place where he had been entertained. The note was from a lady of his acquaintance, and begged for an interview. The Count, it appears, had drunk freely, and probably it was due to that that he displayed a recklessness which was fatal to him. He told his servants that he had an appointment to keep, and though he was pressed to allow attendants to accompany him he refused to do so, saying he was quite able to take care of himself, and, hiring a public carriage, he was driven to a street in the northern part of the city. There he alighted, and what followed is shrouded in mystery to a considerable extent. But what is certain is that he went to a house at the top of the street and a little later that house was found to be on fire. An alarm was raised, the engines were called out, and the fire extinguished before much harm had been done. On entering the smoking building, the firemen found on a bed in one of the rooms the body of Count Cherékof. He was partly undressed. A dagger was thrust up to the hilt in his breast, and a bullet had penetrated his brain. Attached to the handle of the dagger by a piece of ribbon was a card, on which was written:—

"Thus are my wrongs avenged, and

Thus are destroyed the enemies of the people."

It was pretty clear now that the Count had been lured to the house under false pretences, and there assassinated. Whether the house had been wilfully set on fire to hide all traces of the crime or not was not proved; but in all probability the conflagration was accidental, otherwise what would have been the use of the card on the dead man's breast?

The strange tragedy, of course, caused an immense sensation in Russia, for the Count belonged to a very old and aristocratic family, being closely allied, in fact, to the Royal family itself. The Count, however, had never been popular amongst the people. Between the Russian nobility and the lower classes there is a wide line of demarcation, and they hate each other. Oppression in its very worst form is exercised by those in power, and consequently they are detested. It can well be understood, therefore, that the Count's dreadful and tragic end begot no sympathy amongst those over whom he had so long tyrannized, but official and aristocratic Russia was stirred to its depths. The murder showed that the people were still dangerous and to be feared, and something like a panic displayed itself amongst the high-born and the favoured ones of royalty who knew in their hearts that they were all marked men and would meet with a similar doom to that which had overtaken the Count if opportunity presented itself. They lived, in fact, over a mine that might at any moment explode, and so a wail went forth about the inadequacy of the police, and a bitter demand was made that the Count's slayer should be brought to justice. Arrests were made wholesale and indiscriminately. It was as if a fisherman, wishing to catch some particular fish, cast his net into the sea and drew up thousands of other fish which he destroyed in the hope that the particular one he wanted might be amongst them.

It came out then that for some little time previous Treskin had been suspected, and now he was sought for and could not be found. His lodgings were searched and evidence discovered that he had been mixed up in a revolutionary movement that, had it succeeded, would all but have turned Russia upside down. The officials were aghast, the nobles terrified, for the conspiracy was so widespread, its aims so sweeping. More wholesale arrests followed. Men, women, young and old, as well as delicate children, were immured in the dreadful prisons, and the lady—a Miss Dicheskuld—who had sent the letter to the General, which was the means of luring him to the house, was, of course, arrested. There had been an intrigue between her and the Count. He had treated her badly, and in order to avenge herself on him, she had readily joined the conspirators. The letter she had written led the Count to suppose that she was desirous of a reconciliation, and so he had fallen easily into the trap set for him.

This unfortunate young woman was threatened with death if she did not denounce her co-conspirator, and under the fear of this threat she confessed that it was Treskin's hand that had done the Count to death.

It is not an exaggeration to say that law in Russia is based upon a system of persecution, not prosecution as it is in most countries that lay claim to be ranked amongst the civilized nations of the earth. Let a man once bring himself under the cognizance of Russian law, and for ever afterwards, so long as he may live, he is a marked man. He can no more escape from its meshes than can a fly escape when once it has entangled itself in the web of the crafty spider. Only too painfully was this exemplified in the case of Treskin's ill-starred wife, and such cases might be multiplied ad infinitum. The people of the Czar's kingdom are ruled by terrorism in its worst form. The chained slave may writhe under the lash, but he cannot resist it. The caged tiger may roar never so loud, but his roaring has no effect on those who are protected by the iron bars. Give the Russian masses freedom, and what should we see? A mighty whirlwind of human passion—the result of centuries of cruel wrong, of hateful greed, of bitter oppression, of the exercise of power against right—sweeping from one end of the great Empire to the other—a whirlwind that would smite the nobles into the dust and hurl the Czar from his throne, crushed and shattered. This expression of feeling is the outcome of knowledge that has come to me since I unhappily gave up Treskin to his pitiless persecutors. Had I known then what I know now I would have allowed my right hand to have withered before I had stirred a limb to aid the hunters.

If Mademoiselle Dicheskuld thought that in denouncing Treskin she would save herself, she must have been singularly ignorant of her country's law, or otherwise she was the victim of some strange delusion. Death might have been her portion otherwise. As it was, something more dreadful than death was meted out to her. After the hideous mockery of a trial that was not a trial, but an outrage on justice, she was sentenced to banishment to Verkhoyausk, in the Arctic solitudes of Northern Asia. What became of her I know not, but that she perished long before the awful journey of thousands of miles was ended is only too probable.

It might be thought that this act of pitiless vengeance would have satisfied the dripping fangs of the hideous monster termed Russian justice; but not a bit of it. Treskin still lived. Treskin was still at large. What mattered it that his wretched wife had been cruelly persecuted and done to death? What mattered it that his heart had been wrenched and torn and his brain turned by the shame and wrong he had suffered at the hands of a titled scoundrel? All that counted for nothing. He had slain the scoundrel, and that was a high crime in the sight of the Administration. He must be hunted and tracked until snared, and then—ah, what then! We shall see.

Everyone who has travelled in France knows to what an extent police espionage is carried on in that country, but it is nothing compared to what the espionage is in Russia. There your dearest relative may be in the secret pay of the law, and your lightest whisper against the powers that be may lay you unexpectedly in a prison; and yet great crimes are committed, men and women escape, and revolutionary meetings are held. Nevertheless when once a man is suspected, he may be certain that he will have no peace. He will be shadowed night and day. His goings out and comings in will be marked. He is, so to speak, watched through a microscope, so that the most trivial act, which elsewhere would be treated with contempt, is magnified into an offence of the greatest importance. And when the hue and cry has been started it is taken up and repeated from every province, every town, village, and hamlet, and from every housetop, every street corner, every bazaar, market, and shop. A "suspect" who is wanted is, in the most literal sense, hunted. There was no exception made in Treskin's case. He was denounced as one of the most dangerous conspirators and criminals who had ever shown themselves in antagonism to the beneficent institutions of their country, and to the benign and humane rule of the "Little Father," the White Czar. Such a blackened ruffian must be taken. For the good of the countless millions of the free and happy people of enlightened Russia, he would have to be made an example of. The very earth would throb with indignation while he walked upon it. What mattered it that he had been wronged, outraged. What mattered it that his wife and babe had been torn from him, and murdered in the name of the law? What mattered it that his home had been broken up, his life blighted, his heart shattered? These were petty trifles unworthy of serious consideration. A noble of Russia had been assassinated by a plebeian, and a noble of Russia couldn't do wrong, and so his slayer would have to be taken. It is one thing, however, to make resolutions, and another to carry them out. Russia was ransacked, but Treskin found not. By the extensive circulation of public announcements people were warned of the serious penalties they incurred if they gave harbourage to the hunted criminal, or afforded him shelter or support of any kind.

As is usually the case under such circumstances, the officials and the police were seized with a sort of panic. They saw conspiracy in the most harmless gatherings of the people, and wholesale arrests were made. But still the man who was so very much wanted was not forthcoming. Amongst the class to which Count Cherékof had belonged there was loud discontent expressed at the failure of the myrmidons of the law to seize the dreadful Treskin.

They declared that, so long as he was at large, no one of position could sleep safely in his bed. But protest, grumbling, and fear were unproductive of any result, unless it was of proving how unjust and unreasonable men and women can be. Treskin had gone, and, when two years had passed, it may safely be said that in a general way he was forgotten. Russia is always so busy with imprisoning, slaying, or sending political and other offenders to Siberia, that her attention cannot always be occupied with an individual, and so the excitement begotten by the death of Count Cherékof died down, and Treskin's name was uttered no more until one day a strange chance placed his enemies in possession of a clue to his whereabouts.

The clue was furnished to them in this wise. There had come to England as an exile a man by the name of Joseph Pushkin. He was a Russian who had groaned with sorrow at the iniquities of Russian officials and the injustice of Russian law. Of good birth and with ample means at his disposal he might, had he been disposed to suppress his feelings and keep his thoughts to himself, have lived unmolested and have even gained high office in the State. But he was made of different stuff. His was not the nature to remain silent when he saw his humbler countrymen smitten into the dust with oppression and wrong; so he raised his voice, he used his pen, he brought all his influence to bear in a useless endeavour to sweep away the abuses which were such a standing disgrace in the country of his birth. But it was as if a man had attempted to overturn a mountain by pressing his shoulders against it. Pushkin's efforts were just as futile. He was persecuted, he was imprisoned, then banished to the wilds of Siberia. He managed, however, to make his escape en route, and succeeded in reaching our own land of liberty Then he went about lecturing in order that some truths of darkest Russia should be known to the enlightened people of these islands. In one of these lectures he alluded to Treskin's case. He did not mention him by name, but told the story of the wretched man's life as evidence of the barbarities that Christian Russia could perpetrate in the name of justice and right. One of the lynx-eyed spies, who resided in England in the pay of Russia, recognized the hero of the story. This spy was a woman, be it said to her disgrace. She was a writer in the public press, and having more regard for the blood-money that was paid to her than she had for the truth, she constantly described the Czar as a just and humane man, and Russia as a country of beneficent and righteous laws. When she learned that Treskin was in England she lost no time in sending word to her employers, and then there came to London one Prevboski, a Russian detective of considerable fame in his own country. He was authorized to demand Treskin's extradition on the grounds that he was not a political refugee, but a common murderer who had been guilty of a revolting and cold-blooded crime. Of course, it goes without saying not one word was uttered of the fearful wrongs that Treskin bad suffered.

The arguments that Prevboski used, or rather the representations he was authorized to make in the name of the Government of his country, prevailed here, and after considerable discussion it was decided that Treskin should be extradited. But then came the question, Where was he? He had to be found, and the duty of finding him devolved upon me.

At this time my mind was a perfect tabula rasa so far as Treskin was concerned. Up to then I had never even heard his name, consequently I was in entire ignorance of his story, though I knew a good deal of Russian administration and Russian life, my knowledge being derived from residence and travel in the country. I was therefore not prepossessed by any means in favour of Russia. But I did not allow this to weigh when I undertook to look for the fugitive. He was represented to me as a scoundrel of the deepest dye. His crime was pictured as of exceptional atrocity. His victim, it was said, was one of the kindest, most just, virtuous, and humane of men. The cause of the crime—so I was informed—was an insensate and utterly groundless jealousy on the part of the "trebly-dyed villain" Treskin.

Now, making allowance for over-colouring and exaggeration, which your Russian official is much addicted to, it appeared as if Treskin was a vulgar murderer undeserving of sympathy; and it was to the interest of law and order that he should be taken.

Prevboski was a very typical Russian, or rather let me say he was a typical Russian official, for between the official and non-official there is a vast difference. He believed—or affected to believe—that the masses were very much like the wolves which haunt the wild and lonely steppes and the weird dark forests of his native land. They were dangerous when free, and chains and bars were the only things to keep them in subjection. He considered the mode of government and the forms of administration peculiar to his native land perfect, and a model for all other countries, and he regarded the Czar as a ruler by Divine right, who could not err, and who could commit no sin. Prevboski spoke no word of English, so that he was at a disadvantage, and it was arranged that he was to remain quietly in London and wait the result of my efforts.

Necessarily a good deal of publicity had been given to the fact that an application had been made for Treskin's extradition, and this made the task of taking him more difficult. For to be forewarned is to be forearmed, and unless he was an absolute fool he would take means to effectually conceal himself.

The reader need scarcely be told that in London there is a relatively vast Russian population. Many of these are exiles by necessity; others have banished themselves in the hope—often a delusive one—that they will secure a share of English gold. But under any circumstances they enjoy a freedom here impossible in their own country; nor need they go in fear of molestation by the authorities unless they break the law. A great number of these people are Jews, and they may be found congregating together in little colonies in the East End. I began my quest by going into these colonies and making inquiries calculated to elicit some particulars of Treskin's whereabouts. Of course I had been informed that Pushkin had alluded to his compatriot in his lectures, and, therefore, the natural inference was that Pushkin knew where the fugitive was. But it was not in the least likely that he would betray his hiding-place. Having failed, however, in my East End search, I deemed it desirable to get into touch with Pushkin, and he being a public man it was not difficult to find him out.

I ascertained that he was a daily visitor to a restaurant in Soho which was kept by a Russian and was mainly supported by Russians. Here, having supped or dined in Russian fashion, he was to be found nightly, when in town, absorbed in his favourite game of chess, of which he was a passionate lover. I, too, began to frequent the restaurant, and had soon scraped acquaintance with Pushkin; and being myself a fair hand at chess I was enabled to challenge him and so strengthen the acquaintanceship. He was a reserved man under ordinary circumstances, but I soon learned that he could be drawn on Russian subjects, and waxed warm and indignant when the government of his country was alluded to. After a time, when I became more familiar with him, I traded on this weakness, and one evening ventured to ask his opinion of Treskin.

"Ah," he exclaimed, "they will never take Treskin—at least, I hope not. It would be a crime if the British Government should give him up."

"But he has been guilty of a crime," I remarked.

"He has," answered Pushkin, as an angry light gleamed from his dark eyes; "a justifiable crime."

"But surely you do not mean to say that murder is justifiable," said I.

Pushkin looked at me steadfastly for some moments, then he made answer:

"Sir, are you not aware that there are times when murder is not murder? When to remove a tyrant, an outrager of women, an oppressor of men, finds acceptance in the sight of heaven."

"I was not aware of that," I replied, somewhat ironically.

"Then you have much to learn," he retorted.

"So far as my knowledge extends," I said, "I have always understood that we are scripturally informed that 'vengeance is the Lord's.'"

"And yet we read in the Scriptures of men slaying men," he answered with something like a sneer on his face. "But do you not believe that there are times in our human affairs when a man may be made an instrument in the hands of God to remove a tyrant from the earth which he encumbers and darkens?"

I declined to express an opinion on that point, preferring to keep my views to myself; but I urged upon Pushkin that his countryman had certainly outraged man's laws in taking upon himself to slay a fellow without trial and without warning. This caused the Russian to become more and more excited. He declared that Treskin had done a great and noble act; that Count Cherékof, being so full of iniquity and evil, his death was in the nature of a blessing, and that Treskin, instead of being prosecuted, should be hailed as one of the saviours of society I dissented from this view, whereat Pushkin grew more angry, and he vowed solemnly that he would do everything that lay in his power to do to defeat the "infamous design," as he phrased it, of the British Government to give up Treskin, and he added with fiery emphasis:

"But, take my word for it, sir, Treskin will not be given up, for the simple reason that Treskin will not be found."

"Unless he is dead," I responded, "I should say it is highly probable that sooner or later Treskin will be unearthed."

"Treskin is not dead," cried Pushkin, with a bitter smile, "and yet he will baffle the hunters."

I shrugged my shoulders, as if I wished him to understand I was indifferent one way or the other, but my views did not coincide with his, for I thought that, even if I myself failed in the task I had undertaken, somebody else would in all human probability succeed.

My argument with Pushkin had conclusively proved one thing to me, which was that he was not likely to betray his friend if he could help it. But it was very evident that he was aware of Treskin's hiding place, and I set to work to try and think out some plan for getting his secret from him. The only reasonable one, as it seemed to me, was to shadow him, in the hope that he would afford me a clue. Before leaving him on this particular night I said, as a sort of parting shot fired apparently at random, and yet with a definite and deliberate aim:

"Well, if your friend is still in England, you may depend upon it he will be tracked down in time."

"Oh, my friend is still in England," was the answer, with a smile of self-assurance, "but you may depend upon it he will not be tracked down."

To some extent Pushkin had given himself away in his answer, and my object was so far served. He had admitted that Treskin was still in the United Kingdom, and deductively I felt it highly probable that he was in London, because London, being such a huge place, and its population made up of such a heterogeneous collection of nationalities, a man may more easily hide himself there than elsewhere. In London it is not a difficult matter for a man to lose his individuality, so to speak. You become part and parcel of a great whole, but the immensity of the mass of which you are a composing atom causes you in a general way to be no more conspicuous or distinguishable than one grain of sand is distinguishable from another grain of sand on the seashore. This may seem little more than theory, but it is daily borne out by fact, and many a hunted man has been able to lie perdu in the teeming Babylon until the scent has grown cold, and then he has slipped away for good and all. However, vast as London is, it narrows one's sphere of inquiry and action when you are assured that the person you are seeking is one amongst the millions. To him who watches and waits the law of chances are in his favour, and these chances are immeasurably increased when the watcher brings a trained mind to bear on the task he has in hand; for then chance is reduced to something like certainty. There is an old proverb which expresses the fundamental essence of a great truth. It is, "Birds of a feather flock together." He who makes a study of human ways knows how apposite the proverb is to men and women. The ignorant gravitate to the ignorant; the refined to the refined; foreigners to their kind, and so on. A study of this law, which may be said for all practicable purposes to be immutable, enables anyone acquainted with the habits of a particular person whom we may be anxious to discover to turn to the quarter where he is most likely to discover him. Acting on the principle, therefore, I deemed it highly probable that, assuming Treskin was in London, he would be within touch of his compatriots, and particularly with Pushkin. So I watched Pushkin with, if I may so express it, a sleepless vigilance. I was morally certain that sooner or later he would inadvertently deliver his friend into my hands. Let me add point to my statement already made that at this time I believed Treskin to be a mere vulgar assassin, whose deed called for the very severest punishment which his fellow-man could award.

It was about three weeks later—that is, three weeks after I had commenced my shadowing of Pushkin—that I tracked him one day to a villa residence in the "classic regions" of St. John's Wood. It was a small detached house standing in about half an acre of well-kept ground. On the gate was affixed a brass plate bearing the legend, "Madame Marie Lablanc, Teacher of Languages."

Pushkin remained in the house about two hours. Then he came out and went away. A dozen reasons, of course, might have been advanced to explain the motive of his visit to madame, but I said to myself, "When a man goes to a house and stays there for two hours, he must be well acquainted with the inmate or inmates, therefore the assumption is that Pushkin is very familiar with Madame Lablanc."

Arguing thus, I felt sure that madame and the man I was shadowing were friends. That being so, it was likely the lady might be in possession of information, which would be valuable if she could be induced to impart it. Lablanc was a French name, and I was curious to know what connection there was between this French lady and Pushkin, the Russian. A few inquiries pushed in the proper quarter elicited the fact that Pushkin was a pretty frequent visitor to that villa, and as it did not seem to me probable he went there for the sake of studying foreign languages, I thought it curious, to say the least, and I resolved on interviewing Madame Lablanc.

Three days later I knocked at the door of the villa, and inquired for madame, and a natty maidservant showed me into a small parlour that was strongly impregnated with the odour of stale tobacco. In fact I sniffed that odour the moment the front door was opened for my admission, and this was pretty conclusive evidence that someone residing there was a heavy smoker. A few minutes later the door of the parlour was pushed open, and an exceedingly pretty woman of about thirty years of age entered, and with a slight bow inquired my business in the English tongue, that bore not the slightest trace of a foreign accent.

"May I inquire if you are Madame Lablanc?" I asked.

"Oh, no," she answered, "lam madame's niece."

"But you are not French," I remarked with a smile.

"No, my aunt has English connections by marriage," was the somewhat haughty answer.

"I had no intention of being rude," I said apologetically. "May I see your aunt? I wish to make some inquiries about her terms for teaching French and German."

"I will give you a prospectus," replied the lady.

"I should prefer if you will allow me to see madame," I answered.

"Well, you will have to wait for a little while, as she is engaged at present."

I intimated that I was quite prepared to wait, and the niece left me. Twenty minutes or so later the door once more opened, and there entered a solidly-built, neatly-dressed woman with grey hair worn over the temples, brushed behind the ears, and done up in a knob at the back of the head. She wore dark blue spectacles, so that it was impossible to see her eyes, but she had a sallow complexion and a haggard, careworn-looking face. She spoke English fluently, but with an unmistakable accent, and her manner was subdued and reserved. She told me that she taught seven different languages, including Polish and Russian. The result of my interview was I arranged to take lessons in French and German, and to commence on the following day. French I spoke fluently, and German well, but I did not tell her that, and true to the appointment I was there on the following day at the appointed hour. I should mention that she had asked me if I wished to receive my instruction in a class or privately. Of course I decided on the latter, as my purpose would be best served thereby.

There was something about Madame Lablanc that struck me as peculiar. Her voice was harsh and rough, her movements ungraceful, her manner reserved, cold, and brusque. My aim, of course, was to find out if she knew anything of Treskin; but she was so strangely reserved that I did not think it likely she would allow herself to be drawn out, for certainly she showed no disposition to give information on any subject except that in which she was engaged, namely, her teaching. Once or twice I ventured to ask her a question about Russia, and she promptly snuffed me out by saying peremptorily:

"Monsieur, you are here to learn, not to question, except in so far as you may require explanations of any point you don't understand."

I bowed as if thoroughly rebuked, but I resolved to try what I could make of the niece. The one difficulty in the way was to get an interview with her, for let it be borne in mind that I had to be very careful not to arouse suspicion. Chance, however, favoured me. On leaving the house one day I met her returning to it. I stopped and spoke to her, flattered her aunt, and said I thought she was very clever.

"Yes," answered the lady, "she is. She is far too clever to have to grind her life away in the mere drudgery of teaching."

"Why does she not take to something else?" said I.

"What can she take to," replied the niece with some show of irritability. "She is no longer young, and the struggle to live nowadays is fearfully hard. The competition is so keen in every walk of life."

"True, true," I murmured sympathetically. Then after a further brief conversation I was about to part from her, when I stopped and said suddenly, as though the thought had only just occurred to me, "By the way, do you know Pushkin, the Russian?"

Her face coloured, and she seemed to me as if she was confused, nor did she answer me straight off; for her reply was: "Do you know him?" with an emphasis laid upon the "you."

"By sight," I said; "and I saw him coming from your house one day."

"Oh, yes," she answered, recovering herself; "He does come, though rarely. He took English lessons from my aunt."

"Really! That is rather strange, is it not?—that a Russian should go to a French lady to be taught English in England."

"I don't know that there is anything very strange about it. It's a free country, and people can do as they like."

"Certainly, the country is free enough," I responded. "If it were not there would not be such an influx of foreign scoundrels who find their native land too hot to hold them. There is a man by the name of Treskin, for instance—a brutal assassin, as I understand, who has managed to find snug quarters here, and to so far elude those who would like to meet him."

My remark caused the lady to grow very pale, and she seemed for some moments to be strangely agitated. Then in a voice that decidedly quivered she answered, almost passionately:

"Treskin is not a brutal assassin. That is only the tale told by his enemies, and if you knew anything of Russia you would know that if a man has given offence to the Government, and the thousand and one fawning and lying sycophants who do its despotic bidding, he is for evermore marked, and no lie that human brain is capable of forging is considered bad enough to tell about him."

"You espouse Treskin's cause warmly," I said, looking at her fixedly, for I had no doubt from her manner and the way she spoke that she was well acquainted with him.

"As I would espouse the cause of anyone who was oppressed," she answered with composure, for she had quite recovered herself now. "Treskin is a cruelly oppressed man, and I pray to God that the hounds of his infamous Government will never get on his track."

"I should say myself that it is almost certain they will."

She laughed—a strange, sneering, chuckling sort of laugh; a laugh full of meaning, although its meaning was obscured to me then, and she said:

"You may safely venture to wager heavily that he will not be taken. But excuse me. I must go. Good-day." With this abrupt termination to our conversation she turned round and hurried off, and now a feeling took possession of me that I was at last on Treskin's track. It was obvious that he could be no stranger to this lady, and from the warm manner in which she defended him it seemed to me probable that he might be her lover. At any rate I determined to keep in touch with her, impressed with the belief that ultimately I should succeed in obtaining from her some clue to the fugitive's whereabouts. The emotion she had displayed when Treskin was discussed proved conclusively that she might be excited to a pitch when she would in all likelihood make some admission which would prove valuable to those who were seeking the fugitive.

It was about a week later, during which I had not seen the niece, that I was with Madame Lablanc one morning reading German with her. It was cold weather, and she wore a loose sort of dressing-gown lined with fur. She rose somewhat suddenly from her seat to stir the fire, and in doing so something from an inside pocket in her gown fell heavily to the floor. To my astonishment I saw that it was a revolver. I stooped and picked it up, when with an angry movement she snatched it from me. The next moment she looked abashed and confused. "Excuse me," she stammered, apologetically, as she thrust the weapon into her pocket again. "I am a stupidly nervous woman and for years have carried a revolver, though I don't believe if the necessity were to arise I should have the courage to use the thing. Indeed I don't even know how to use it."

Her manner of saying this was insincere, and carried no weight with me, for I was sure that she could be a very ugly antagonist indeed with a weapon like that in her hand. Nor did it seem to me in the least likely that she was ignorant of its use, as she pretended to be.

"It is a somewhat dangerous toy for a lady to carry about with her," I remarked, "and you will pardon me for saying that you must be impressed with an idea that an occasion may suddenly arise when you will find it necessary to defend yourself with that weapon."

"Defend myself from whom and what?" she asked sharply.

"Madam," I answered, "I am not the keeper of your thoughts."

The discussion was not continued, as she resumed the reading lesson we were engaged upon.

This little incident of the revolver was not lost upon me. It set me pondering, and I began to compare notes, with the result that I came to the conclusion there was a good deal of mystery about Madame Lablanc which required explanation. When next I visited her I scrutinized her closely, and felt convinced that the grey hair which was such a conspicuous feature, and which was so carefully done up, had never grown upon her head. It was, in fact, a wig, but so admirably made, and simulated Nature so closely, that it was well calculated to deceive anyone. Now, why should she wear a wig of this kind? And why did she carry a revolver? To the first question I answered to myself—"For some strong reason she is concealing her identity." To the second—"Should her disguise be penetrated she would bring the weapon into use, either against herself or against someone else."

That night I called upon Prevboski, the Russian detective.

"Have you ever seen Treskin?" I asked.

"No. But I have numerous photographs of him taken at various times and in various positions."

The photographs I carefully inspected, studying the features, in fact, in all their detail, and gradually a suspicion that had been haunting me became less vague than it had been, and when I returned the photographs to the Russian I felt almost sure that I had at last been successful in my search, and had found the much-wanted Treskin.

"I want you to accompany me the day after tomorrow," I said to Prevboski, "to a certain house, and bring some of those photographs with you."

"Have you discovered Treskin?" he asked eagerly.

I intimated that I had some reason to think we should discover him; so the arrangement was made, and on the appointed day Prevboski and I presented ourselves at Madame Lablanc's residence, were duly admitted by the servant, and ushered into the room where I had been in the habit of having my lessons. We waited some little time before anyone came to us. Then there entered the niece, who eyed the stranger keenly and suspiciously.

"This is an acquaintance of mine," I said. "He is a Russian, and is desirous of learning English."

This latter statement was true, in fact, for he was very desirous, indeed, of acquiring a knowledge of the English tongue, though he had no intention then of becoming a pupil of Madame's.

"Does he not understand English at all?" asked the niece still looking at him.

"I don't think he understands a word," I replied.

"But has he means to pay for his lessons? You will pardon me asking that, but we know from experience that Russian refugees who come to this country are often in sore pecuniary straits, and my aunt cannot afford to teach for nothing."

"I think, miss, that I may venture to assure you that if this gentleman should take lessons he will most certainly pay for them. But perhaps your aunt will see him. She can converse with him in his own tongue, and satisfy herself."

The niece assented that that was perhaps the best course, and she left the room; but the expression of her face and something in her manner gave me the idea that she was troubled and anxious. Presently she returned in company with her aunt, and I noted that Madame, so far as I could judge, fixed her eyes on the Russian. But I inferred this more from the aspect and position of her face, for the blue spectacles made it impossible for me to see the eyes. She put a few hurried questions to Prevboski in the Russian language, and he answered her as rapidly; and I was conscious that her anxiety increased. On our way to the house I had mentioned my suspicions to him, and it was evident he was influenced by them, for with a sudden and adroit movement he snatched at Madame's grey hair, partly tearing it away, and revealing the fact that it was a wig. With a wild cry of alarm the niece sprang between them, and, throwing her weight against him, hurled him back, while the pseudo Madame Lablanc got between us and the door, and, drawing a revolver, covered us, while a look of despair and stern determination was on her haggard face, or rather his face, for we had found Treskin, and the niece, as was soon made manifest, was his loyal and devoted wife.

"Do not attempt to touch me," he cried in a half-frantic tone, "or, as the sky is above, you are dead men."

The tableau was certainly a dramatic one, for this desperate, hunted man was not likely in such a moment to be influenced by any thought of the after consequences if his threat was carried into effect. My companion and I were certainly at a disadvantage, for between us and Treskin stood his beautiful wife; unarmed, it was true, but ready to sacrifice herself if needs be. If we made a rush at him, we would have to hurl her out of the way, and in the brief seconds required for that, Treskin could send his bullets speeding. There was the chance, of course, of his missing; or, on the other hand, of his hitting her or us. Anyway, we wished to avoid a tragic ending to this dramatic affair; but before we could take action, Treskin backed to the door r opened it, and backed out, while his wife covered his retreat. Then, acting in concert, Prevboski and I darted forward, and gained the passage in time to see the unfortunate man disappearing up the stairs, and in a few moments a door slammed violently.

We followed with all speed, and hammered on the door of the front bedroom, where he had sought refuge. Suddenly the door was flung open, and Treskin, stripped now of his false hair and blue spectacles—which, by the way, were as much of a necessity as part of his extraordinary disguise, for he suffered from some affection of the eyes—stood in the threshold. There was no anger, no fire, no passion in his face; it was a wonderfully gentle, mild face, and more like a woman's than a man's.

"Gentlemen," he said, in a voice that was heart-cutting in its pathetic sadness, "I yield myself your prisoner. It is useless my fighting against the stars or trying to avert my destiny. I have been a fool to suppose I could long elude the scent of the Russian bloodhounds. But I am a political refugee, and the English Government dare not give me up. You must give me a little time to collect my papers, to put my affairs in order, and to console my beloved wife, whose devotion to me is worthy of being immortalized in an epic poem." Turning to me he handed me the revolver, which up to this moment he had held with his finger on the trigger, and he said, "You have done your work well, and lured me into a trap; but I suppose it is your business, therefore I will not blame you. You are an Englishman, however, I presume, and I may therefore look for fair play at your hands. I could expect none from this man," looking contemptuously at Prevboski; "he would treat me as if I were a wild beast."

I hastened to assure Treskin that he would receive every consideration, and his first act was to descend the stairs in search of his wife, whom he found lying in a swoon on the floor of the room. Bending down, he raised her with an infinite tenderness, and as he kissed her white face he sobbed like a stricken child. A man who could weep over a woman, as he wept then, could have very little of the savage in him. I am not ashamed to own that it affected me, and I was obliged to turn away. But Prevboski looked on with stolid indifference, and grunted out an expression of impatience.

An hour later we conveyed the unfortunate Treskin to prison, and so far my part ended. The disguise that he had assumed and so well kept up had thoroughly deceived everyone not in his secret, and he had been able to earn a good income by his linguistic accomplishments. He had been married to his English wife about a year. She was the daughter of highly-respectable people, who had made a small fortune in business and retired. Her love and devotion to her wretched husband were of that nature which passeth words; and, with an eloquence of a broken-hearted woman, she pleaded his cause in the public press and told the moving and pathetic story of his life, every detail of which was subsequently confirmed. But, notwithstanding this, and in spite of an almost universal protest, he was given up and conveyed to Russia with Prevboski—the poor, grief-stricken wife accompanying him; for no persuasion, neither on his part nor on that of her relatives, could prevent her from sacrificing herself, for truly it was a sacrifice.

As most people are aware, it is not an easy matter for anyone here to follow the career of a prisoner in Russia, for the ways of the Russian prison administration are mysterious and dark, few outsiders are able to learn what goes on behind the iron bars and the ponderous doors which all too securely guard the victims of so-called justice. But from special sources of information I ascertained after a considerable time that Treskin was kept for a whole year in prison before he was brought up for trial. Then it was a hideous mockery to try him, for his brain had given way, and he was far gone in consumption. Nevertheless, be it told to the eternal disgrace of those who were responsible for it, he was sentenced to banishment, his destination being Northern Siberia. In due course he started on the dismal and dreadful journey, accompanied by his heroic wife. But when the Ural Mountains had been crossed he was in a dying state. He had, indeed, been dead to the world for some time, for his mind had quite gone. He was left behind in an étape, where he lingered for a few weeks, and then departed to where man's persecution could no longer affect him. His wife, who had so far borne up with heroic fortitude, broke down utterly crushed and shattered beneath the blow, and in a moment of unbearable sorrow she put an end to her own wrecked life. It is a pitiable story, and I end as I began by saying bitterly indeed do I regret that ever I played any part in the taking of Treskin.

EVERYONE who lays claim to the possession of even ordinary powers of observation, must frequently have been struck by the way in which mere chance seems to influence and control the lives of human beings. Some trifling and unforeseen circumstance has often been the means of entirely changing one's destiny. Read the histories of prominent men and women, kings and queens, statesmen, lawyers, clergymen, authors of both sexes, of soldiers, and sailors, and it will have to be admitted that "chance" is a factor in the human sense which frequently upsets all our calculations. It will, of course, be admitted that "chance" is but another name for luck, good or bad as the case may be, and people may be found who deny the existence of such a thing as luck; but Professor de Morgan, who was one of the greatest of mathematical writers this century has produced, and whose classic on "The Theory of Probabilities" is too well known to need more than a passing reference here, was firmly convinced that some people were born naturally lucky and others unlucky. He himself says, "The assertion that there is something in luck is one which I do not think of questioning;" nor will any other man think of questioning it unless he is singularly obtuse, or singularly blind to the signs that come in his way. Indeed, if anyone who has read thus far will pause to take a retrospective glance at his own life he will perhaps be surprised to see how often that life has been influenced by what appears as strokes of bad or good luck. My story will, I think, lend peculiar point to the foregoing argument, which has an undeniable appositeness to what I have to tell. I might with perfect justification of the title have called this story "By the Spin of the Halfpenny," for it was due to the twirling of that humble coin of the realm that the events I am about to narrate were brought about.

It chanced one summer in the distant past that I was rusticating with a dear friend in the historic precincts of the grand city which has not inaptly been dubbed the "Modern Athens" by some enthusiastic Scotsman. The natural beauties of its situation no one can deny, but there are certain architectural excrescences which detract a good deal from its artistic beauty. Nevertheless, Edinburgh has a fascination all its own, and is particularly attractive in the long, warm days, when blue skies and bright sunshine lend a charm to even the most squalid of places. The friend I allude to has long since been numbered with that mighty majority of the human race, between whom and us is the mystery of unbroken silence, and which oft prompts the lonely-hearted to dumbly exclaim:

"Oh, for the touch of a vanished hand,

And the sound of a voice that is still!"

The grip of ray friend's hand was that of an earnest, genuine man; and his cheery voice was like the mellow strains of a silver flute. We had been long "acquain," and we had wandered through many strange lands, and seen many strange scenes together. Ah! and alas! how evanescent are the joys and pleasures of life, and all too soon we gaze with tearful regret on the white tombstones of our dear ones dead and gone! But I must not moralize, though the temptation to do so is strong when one remembers companionships that Death has destroyed. Well, my friend and I had been spending some delightfully pleasant days in the northern city, when, as we were lounging and enjoying our matutinal pipe, after a hard day's work the previous day, he suddenly exclaimed, with the easy familiarity warranted by long and tried friendship, which had been unmarred by even the lightest rift or the tiniest shadow:

"I say, Dick, old fellow, what are you going to do to-day?"

"Loll and dream, for I am tired," I answered.

"Bosh," said he, with his wholesome laugh, "You'll do nothing of the sort. I shall carry you off somewhere."

"No, you won't, dear boy, I'm in for a day's laziness."

"You are in for a day's outing," he returned. "The balmy atmosphere and bright sky woo one to Nature's bosom. That touches you? Eh?"

I asserted with emphasis what he already knew, that I was one of Mother Nature's most devout of worshippers; but I added that there were times, owing to the weakness of the flesh, when even a devotee preferred the dreamy indolence of the lotus-eater to the toil of the pilgrim; and at that particular moment, and in that particular instance I wished to sup of the drowsy mandragora and see visions.

"By Jove," he cried cheerily, "when a fellow talks of seeing visions it's a sign that he is growing mentally weak. Now, then, I'm going to take you off to Stirling, thence we'll do a tramp across the Trossachs, and as we go I'll read out 'The Lady of the Lake' to you, for it's one of my favourites, and I'm letter perfect in it. That will clear the cobwebs from your brain, and you'll talk no more of visions unless it be visions of the beautiful 'Lady of the Lake.'"

"Get thee behind me, tempter of tempters," I growled. "I fain would be alone, and yet you tempt me with a song of enchantment, and I am weak."

"Aha, you yield," he exclaimed.

"No, I am as inflexible as tempered steel."

"The spin of a coin of the realm shall decide it," said he. "Are you on?"

"Yes. I cry 'heads,' and I'm sure to win."

He drew forth from his pocket a halfpenny, tossed it into the air with a dexterous jerk of the thumb, and let it fall upon the table.

"It's tail," he roared, as the coin settled, and so it was. "The fates are against you; so stir yourself. There is a train in half an hour, and see to it that the tobacco pouch is well filled. Fail at your peril. Come, time and trains wait for no men. At least trains do sometimes, but not for humble men like us."

Who could resist such a delightful despot as he was? I therefore tacitly complied with his imperious command, and having procured my hat and stick and light overcoat, we set off to the station, and soon were enjoying that superb view which is seen from the "Queen's Seat" on the wall of Stirling's ancient Castle. If we had ordered weather to our own liking, we could have had nothing better than the sample we were favoured with on that glorious day. A few fleecy clouds that resembled nothing so much as drawn out white wool, flecked the azurine sky, and there was a clearness—a plate-glass-like atmosphere, not often experienced in the northern regions of the kingdom. The passionate larks soared upwards with a burst of melody that seemed to gush forth like a flood, filling the palpitating air; and mingling with it was the rythmical murmur of flowing water, while the senses were lulled with the aroma of the scented breeze that blew over vast expanses of field and wood. My friend felt the influence of these things as much as I did, for deep in his manly heart was a rich vein of pure sentiment that found its expression in a worshipful silence, and so we spoke not, but gazed dreamily over the quivering landscape, each thinking the thoughts that were in accord with his respective temperaments, and the particular mood of the hour. Suddenly our dream was broken by the soft voice of a woman exclaiming—"Isn't it lovely!"

The "lovely" jarred upon my senses, for it is a verbal barbarism for which women are responsible; and turning I beheld a gaily dressed pretty woman of about twenty-five in the companionship of a sour-visaged, dark complexioned man upon whom she was leaning with her gloved fingers of both hands interlocked about his arm, and her brown eyes fixed on his face as if she were pleading to him to at once endorse her verdict with regard to the "loveliness" of the landscape over which the wand of summer had been passed, and called forth all its innate beauty, until in colouring, artistic finish, and detail, it presented a perfect picture of living nature.

The man was forty if he was a day. His hair was cut close, and mingling with its almost jetty-blackness, were grey streaks. His cheeks and chin were clean shaved; but a grey-streaked moustache drooped not ungracefully over his lips. His face was not a good one. There was a shifty foxiness in the dark eyes, and a certain cast of feature not altogether easy to describe, which irresistibly suggested an evil, a plotting mind. As you looked at him, and took in the points of his physiognomy you could not associate him with a rugged, frank, outspoken disposition.

You who are disposed to deny that something—and a big something too—of the human mind cannot be read in the first glance you get of a face must have studied your fellow-men to little advantage. Although I could lay no claim, even in the smallest degree, to the wonderful gift which distinguished the renowned Lavater, I had, both intuitively and by experience, the power of drawing certain more or less accurate deductions from expression, contour, and detail of the face. And so I found myself studying this man until I was sure of two things. Firstly, that he was an enemy to well-ordered society; secondly, that at some time or somewhere I had looked on him before.

His style of dress was flashy and vulgar. The cut of his trousers—tight at the knees, bell-shaped at the bottom—clearly indicated the coarse and narrow understanding which is utterly incapable of distinguishing between meretricious gaud and true art. He wore a loud crimson necktie, held in position by a jewelled ring, the jewels of which might or might not have been genuine; it was impossible to tell from that distance. He had rings on his fingers also—far more than any man of refined taste would care to wear. His coat was a rakish, cheap-cut garment, and on his gaudy, speckled waistcoat reposed a massive, cable-patterned chain, with numerous seals pendant therefrom. He wore a broad-brimmed, soft felt hat that was posed not ungracefully on his head, and which served in a minor degree to redeem the vulgarity of his personal appearance.

If I had been asked there and then to have passed a verdict upon this individual I should have said that he possessed within him the prima materia of an unprincipled adventurer; one who had no respect for the laws of meum and teum; and to whom—given a certain concatenation of circumstances—human life would have had no sacredness.

As the well-known proverb "Birds of a feather flock together" expresses an irrefragable truth, I need only say at this juncture the lady who accompanied him was neither his superior nor his inferior. She was on a level with him. I have remarked that she was pretty So she was, but it was a coarse prettiness that would only bear looking at as a whole and not in detail. By the law of affinities she had been drawn towards him by having something in common, that something existing in a similarity of tastes, ideas, and aspirations. The relationship in which they stood to each other was in one sense not difficult to determine. They were lovers; that was evidenced in her pose, her look, her general manner, and they had the appearance of a very newly-married couple on their honeymoon tour.

Now, having surveyed and weighed, so to speak, this commonplace couple, and drawn my own inferences as to the value they were likely to set on the rules of ethics generally recognized by well, self-governed people, I might have dismissed them from my mind, and turned to the more agreeable contemplation of the superb panorama which engirt us round about, and was enhanced in picturesqueness by the hoary towers of the time-stained castle, had it not been for the fact that the man's face awakened some dormant memory. It was a phantom memory—as intangible as a phantom, as fugitive as a phantom. I had seen the face before, but where, when, and under what circumstances I could not possibly recall just then. When your brain is filled with many photographs of people you have seen and known at some far-off time you cannot always put your finger on any particular one that happens to have become faded and dingy by the lapse of time, and say, "That is So-and-so," and fix the date of your meeting.

The man replied to the woman's remark by saying:

"Yes, it ain't bad; but I want some grub. I'm precious hungry."

Then he looked down into her upturned face with an endearing expression, and they moved away.

For some moments I stood gazing after them with an aroused curiosity, and trying to drag forth from the storehouse of my memory something wherewith I might identify the gentleman. Suddenly like a flash of light the remembrance I sought came to me. He was by birth a Welshman, whose real name was Llewellyn Jones, but who passed under many aliases. I had been largely instrumental in bringing him to book many years before for an audacious forgery, and as he had been previously convicted he received sentence of a long term of imprisonment. As I recalled this I further remembered that he was regarded as a clever and daring rascal, who flew at big game.

"What is he doing here?" I asked myself. "What is he up to? Has he just married that woman? Does she know the life he has led? Is she an innocent dove that has been lured into the fowler's net?"

I had little hesitation in answering "No" to the latter question. She was not dressed in the plumes of a dove, nor were her features expressive of a dove's guilelessness. It was infinitely more likely she was a helpmate in the fullest sense, and that she was willing to follow him in his course, whether for good or ill. Ill it would be no doubt, for a man ingrained with rascality as he was was not in the least likely to suddenly turn saint.

It may be imagined that I was more than ever interested in these people now that I had determined his identity, and I resolved to learn something more about them. If he was leading an honest life well and good. There would be no harm done, since he would be unaware of my solicitude about his welfare, and if it were otherwise I might be able to render some service to the State by spoiling his plans if they were opposed in any way to the law. My friend had drawn from his pocket a small sketch-book, and was amusing himself—he was very clever with the pencil—by rapidly sketching in outline little bits of the landscape, so I turned to him and said:

"I will leave you here for a while. I want to try and solve a riddle. I will be back soon. Wait for me."

He merely nodded an assent to my request, for he was absorbed in his amusement, and I moved off in the track of Jones and his companion. I sighted them just as they were going out of the Castle gateway, and followed them to an hotel, where I soon ascertained they were staying under the name of Mr. and Mrs. Cotswold. They had arrived the previous night, and had intimated their intention of departing on the morrow. They had come down from Edinburgh, and from inquiries they had made it was gathered that they intended to pursue their journey through the Trossachs, and proceed to Glasgow. The manager of the hotel regarded them as a newly-married couple, as they seemed very loving to each other, and Mr. Cotswold was looked upon as a man of some importance, inasmuch as he had received numerous telegrams although he had been there so short a time. "Numerous telegrams" was evidently a standard of respectability and importance, according to the views of that particular hotel-keeper.

Of course, I breathed no word of suspicion against the reputation of "Mr. Cotswold," who was considered to be a good customer, for he had ordered wine freely the night previous at his dinner. But I telegraphed in cipher to certain official quarters asking if any information could be given me concerning Llewellyn Jones, who had been convicted of forgery. In due course I received for answer the following:—

"NOTHING AT PRESENT KNOWN OF JONES. HE WAS DULY DISCHARGED AFTER SERVING HIS SENTENCE, AND IS SUPPOSED TO HAVE LEFT THE COUNTRY."

In the meantime, that is between the despatch of my telegram and

receipt of the answer, I had returned to my friend who had been

anxiously waiting for me, as he was bent on a pedestrian tour. But

I explained to him the little business I had in hand, which was

either to justify my suspicions or satisfy myself that Llewellyn

Jones alias Cotswold was leading an honest life. So my

friend yielded to my request that we should only make a short

stroll, and return to the hotel in time for dinner. On getting back

from our walk I found the telegraphic answer to my question

awaiting me, and if it did nothing else it proved that for the time

being at least Mr. Jones had passed from the ken of the people who,

it might be supposed, had some interest in keeping an eye upon

him.

It must not be forgotten by those who are disposed to think that there was no justification for watching Jones that he came into the category of an habitual criminal, that the law of averages was all in favour of an habitual criminal, after a long term of imprisonment, reverting to his old ways. For my own part, I was morally certain that Jones was still a dangerous person. But under any circumstances, if for no other reason than that of gratifying an idle curiosity—if you so will it—I was determined to know what Jones's little game was. When I had last brought him to book he had been described as "a single man," and there was every reason to believe that description was accurate.

Now, however, it appeared as if he had joined issues with one of the opposite sex, and had united his destiny to hers; and as I felt certain she belonged to the same genre as he did, it seemed to me in the highest degree probable that when two evil things came together evil would be the result. So as I had time on my hands I thought I could not spend it better than by trying to discover how Jones got his income. It was a very interesting problem, and one which—in the interest of truth and right—was well worth solving.

During the afternoon "Mr. and Mrs. Cotswold" were absent; they hired a carriage and pair, and went for a long drive. That act argued that they had a well-lined purse; and the argument was strengthened by the little incident which I learnt casually that that very morning Mr. Jones, or Cotswold, as he called himself, had obtained change for a twenty-pound Bank of England note at the bar of the hotel. Now, was it not a legitimate question to ask:

"How was it that this man—a convicted forger—who had but recently come out of prison, was so well provided with money?"

The question was one which I felt ought to be answered correctly, and I resolved that I would answer it. I was no longer desirous of dreaming the dreams of the lotus-eater; nor of enjoying the drowsiness, begotten of the potent mandragora. All my faculties were keenly alert. I had been suddenly presented with a problem, which was well calculated to afford me the keenest interest, and I settled down to my self-imposed task with a feeling, that if it was not enthusiasm that spurred me, it was something very much like it. My friend and I passed the afternoon in strolling about, and he having the artist's love of the beautiful, watched with rapt admiration the western sun working out prismatic effects of colour, as it slowly sank in the fervid sky, and—

"Turned the cloddy earth to glittering gold."

It was all very beautiful. The sky was a burning glory of fretted fire, and in the amber light the inanimate things of earth seemed transfigured and to take on a splendour, until there was suggested to the beholder—at least to me—those wonderful and daring flights of genius which Martin gave evidence of when he gave to the world his great picture—The Plains of Heaven. Gradually the colours faded and the purple of the gloaming stole softly over the scene. Then we rose from the mossy bed on which we had been reclining, and made our way back to the hotel, which we reached as a noisy gong was calling the hungry to dinner.

A goodly company in point of numbers sat down to the table d'hôte, and my friend and I secured seats on the opposite side of the table to that at which Jones and his wife sat. I had reason to suppose that there was no likelihood of Jones recognizing me, for when I ran him down on the last occasion I had scarcely ever come in personal contact with him, and my plan was to endeavour to draw him into conversation after dinner, when the gentlemen retired to the smoking-room—I had already ascertained that he was a smoker—and by means of carefully guarded questioning find out, if it could be done, where he was domiciled, and if he was really on his honeymoon tour. A little incident, however, that occurred during the dinner-time, saved me the necessity of that course, and here again the law of chance or luck—call it what you will—favoured me.

When the dinner was about half over a waiter brought in a letter to Jones, who, with manifest eagerness, tore open the envelope, unfolded the letter, perused it with a gratified smile, whispered something to his wife as he handed the letter to her to read. She too read it with a smile of gratification, and they exchanged looks, which indicated unmistakably that the information contained in the letter afforded them complete satisfaction. The woman then returned the paper to her husband, who at once proceeded to tear it and the envelope into pieces, which he cast behind him into a fireplace, which, for the nonce, had been turned into a little arbour of living plants in pots. When the dinner had ended, and the guests departed, I strolled round to that fireplace, picked up every shred of the torn paper, and slipping them into my pocket-book I went to the bedroom I had engaged for the night. Then lighting the candle I sat down at the table, and arranged all the pieces in their proper order. This, as may be supposed, was not done without a considerable amount of trouble, but when at last I succeeded in my task I found that the envelope bore the Manchester postmark and the date of the previous day, and the superscription was:

John Cotswold,

Esq.,

Royal Hotel,

Stirling, N.B.

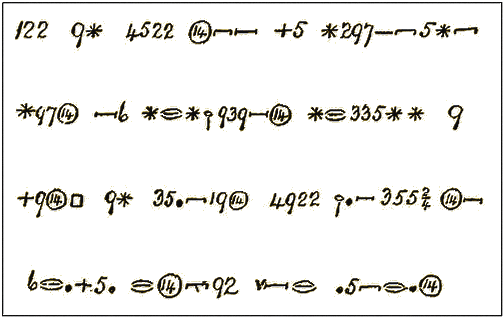

The letter itself was written in cipher, of which the following is a copy:—

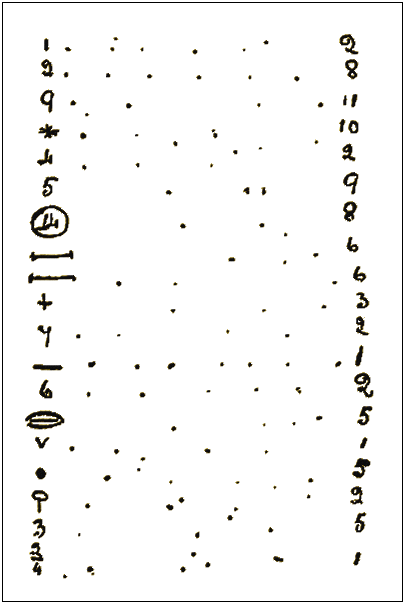

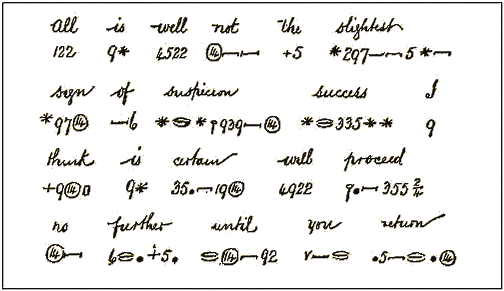

It will be seen from this table that there were nineteen signs. 9 was repeated eleven times, and the next highest was *, while v, 2/4, and — only appear once. Now, as everyone knows, amongst the most frequently used characters in the English language are E and I, and bearing this in mind I felt that I had got the key to the enigma.

Let me proceed to explain. I noted that 9 occurred most frequently, and * followed next in order. As E is more frequently used than I, I tried E to begin with, thus:

E 2 2

Now came the question, what did the 2 stand for? I tried various combinations without getting any further. The twenty-second letter of the alphabet being V, wouldn't fit in. Then it flashed upon me that the 2 was probably used as a divisor, and L being the twelfth letter in the alphabet the 2 might stand for it. Twice 6 being 12, I therefore got the word—

E L L

That, however, conveyed no intelligible meaning; but the double L suggested naturally that A should be substituted for E, when the word

A L L

appeared. Assuming that to be correct, it was clear that as A was the first letter of the alphabet it was represented by 1. This helped me on, and I at once jumped to the ninth letter, which, of course, is I. But now I was perplexed by the *, which was a frequently-used sign. Yet it evidently did not represent E, so I tried N T F; but having regard to the number of times it was repeated in the cipher, S seemed the most likely, and it gave me—

ALL IS

In order to determine the next word—and having discovered that 2 stood for L—I wrote down the following—

ALL IS LL

The points represented the missing letters, which I at once filled in by W E.

ALL IS WELL.

Here I had a perfectly intelligible phrase, and it determined that W and E were represented by 4 and 5. "But, why," I asked myself, "did 4 stand for W, and 5 for E?" The vowel was the 5th in the alphabet, but W certainly wasn't the fourth. "Yes, it is," I mentally exclaimed. "It is the fourth from the last letter," and as I could account for the 4 in no other way, I was content to let it stand so.

After a little puzzling I took (14) to stand for a single letter, and N being the fourteenth in the alphabet I got this sentence—ALL IS WELL. N.

Two letters were wanted to follow the N, and it was necessary that one should be a vowel, and by trying all the vowels I hit upon O, which at once suggested T, which gave me the word not. The next following in the cipher was +5. Knowing that 5 stood for E, I put down the sentence—

ALL IS WELL. NOT E

It was difficult to find a single letter that would make sense, so that it seemed pretty clear + must represent two letters, and after various trials I was sure it was TH.

ALL IS WELL. NOT THE

Knowing what S L and I were represented by, I was now enabled to expand the sentence:

ALL IS WELL. NOT THE SLI TEST