RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

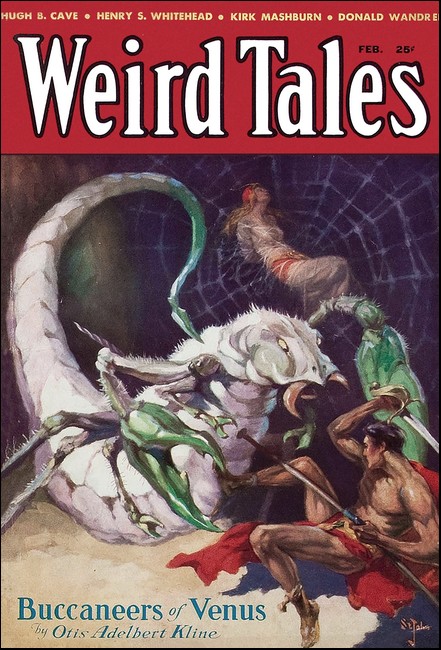

Weird Tales, February 1933, with "The Chadbourne Episode"

A shuddery graveyard taleof ghastly shapes glimpsed in the moonlight, and little, reddish, half-gnawed bones scattered about the tomb in the Old Cemetery.

PERHAPS the most fortunate circumstance of the well-nigh incredible Chadbourne affair is that little Abby Chandler was not yet quite seven years of age on the evening when she came back home and told her mother her story about the old sow and the little pigs. It was July, and Abby with her big tin pail had been up on the high ridge near the Old Churchyard after low-bush blueberries. She had not even been especially frightened, her mother had said. That is what I mean by the fortunate aspect of it. Little Abby was altogether too young to be devastated, her sweet little soul permanently blasted, her mentality wrenched and twisted away from normality even by seeing with her round, China-blue eyes what she said she had seen up there on the steep hillside.

Little Abby had not noticed particularly the row of eight or nine pushing, squeaking, grunting little pigs at their early evening meal because her attention had been entirely concentrated on the curious appearance, as it seemed to her, of the source of that meal. That old sow, little Abby had told her mother, had had 'a lady's head...'

There was, of course, a raison d'être—a solution—back of this reported marvel. That solution occurred to Mrs. Chandler almost at once. Abby must have heard something, in the course of her six and three-quarter years of life here in Chadbourne among the little town's permanent inhabitants, some old-wives' gossip for choice, about 'marked' people; whispered 'cases' of people born with some strange anatomical characteristics of a domestic animal—freaks—or even farm animals 'marked' with some human streak—a calf with a finger growing out of its left hind fetlock—things like that; animals quickly destroyed and buried out of sight. Such statements can be heard in many old New England rural settlements which have never wholly let go the oddments in tradition brought over from Cornwall and the West Country of Old England. Everybody has heard them.

Chadbourne would be no exception to anything like this. The old town lies nestling among the granite-bouldered ridges and dimpling hills of deep, rural, eastern Connecticut. In any such old New England town the older people talk much about all such affairs as Black Sabbaths, and Charmed Cattle, and Marked People.

All of that Mrs. Chandler knew and sensed in her blood and bones. She had been a Grantham before she had married Silas Chandler, and the Grantham family had been quietly shrinking and deteriorating for nine generations in Chadbourne along with the process of the old town's gradual dry-rotting, despite the efforts of such of the old-time gentry as may have survived in such places.

For gentry there are, deeply imbedded in New England, people who have never forgotten the meaning of the old noblesse oblige, people who have never allowed their fine sense of duty and obligation to lapse. In Chadbourne we had such a family, the Merritts; Mayflower passengers to Plymouth in the Massachusetts Colony in 1620; officers and trustees for generations of Dartmouth College in New Hampshire and of Trinity College, Hartford, Connecticut. We Canevins, Virginians, were not, of course, of this stock. My father, Alexander Canevin, had bought up an abandoned farm on a Chadbourne ridge-top about the time of the Spanish War. In that high air, among those rugged hills and to the intoxicating summer scents of bayberry-blossoms and sweet-fern—which the Connecticut farmers name appropriately, 'hardhack'—I had sojourned summers since my early boyhood.

Tom Merritt and I had grown up together, and he, following the family tradition, had gone to Dartmouth, thence to the Harvard Medical School. At the time of little Abby's adventure he was serving his community well as the Chadbourne general practitioner. But for the four years previous to his coming back and settling down to this useful if humdrum professional career, Thomas Bradford Merritt, M.D., had been in the diplomatic service as a career consul, chiefly in Persia where, before his attachment as a step up to our legation in Teheran, he had held consular posts at Jask, a town in the far south on the Gulf of Oman; at Kut-el-Amara in the west, just south of Baghdad; and finally at Shiraz, where he had collected some magnificent rugs.

The autumn before little Abby Chandler's blueberrying expedition Tom, who acted as my agent, had rented my Chadbourne farmhouse just as I was leaving New York for my customary winter's sojourn in the West Indies. That my tenants were Persians had, it appeared, no connection at all with Tom's long residence in that land. They had been surprised, Tom told me, when they found out that the New England gentleman whose advertisement of my place they had answered from New York City was familiar with their country, had resided there, and even spoke its language passably.

In spite of this inducement to some sort of sociability, the Persian family, according to Tom, had comported themselves, toward him and everybody else in Chadbourne, with a high degree of reticence and reserve. The womenfolk had kept themselves altogether secluded, rarely leaving the house that winter. When they did venture forth they were always heavily muffled up—actually veiled, Tom thought—and only the edges, so to speak, of the mother and two daughters were ever to be observed by any inhabitant of Chadbourne curious to know how Persian ladies might look through the windows of Mr. Rustum Dadh's big limousine.

Besides the stout mother and the two stout, 'yellowish-complected', sloe-eyed daughters, there was Mr. Rustum Dadh himself, and two servants. These were the chauffeur, a square-built, tight-lipped, rather grim-looking fellow, who made all his own repairs to the big car and drove wrapped up in a furlined livery overcoat; and a woman, presumably the wife of the chauffeur, who never appeared outside at all, even on Friday nights when there was movies in Chadbourne's Palace Opera House.

All that I knew about my tenants Tom Merritt told me. I never saw any of the Rustum Dadh family from first to last. I had, in fact, completely forgotten all about them until I arrived in Chadbourne the following June some time after their departure and learned from Tom the bare facts I have set out here.

On a certain night in July that summer the Rustum Dadhs were farthest from my thoughts. It was nine o'clock, and I was sitting in the living-room reading. My telephone rang insistently. I laid down my book with a sigh at being interrupted. I found Thomas Bradford Merritt, M.D., on the other end of the wire.

'Come on down here as soon as you can, Gerald,' said Tom without any preliminaries, and there was a certain unusual urgency in his voice.

'What's happened?' I inquired.

'It may be—ah—something in your line, so to speak,' said Doctor Merritt; 'something—well—out of the ordinary. Bring that Männlicher rifle of yours!'

'I'll be right down,' said I, snapped up the receiver, got the Männlicher out of my case in the hall where it is in with my shotguns, and raced out to the garage. Here, of a certainty, was something quite strange and new for Chadbourne, where the nearest thing to anything like excitement from year's end to year's end would be an altercation between a couple of robins over a simultaneously discovered worm! 'Bring your rifle!' On the way down to the village I did not try to imagine what could possibly lie behind such a summons—from conservative Tom Merritt. I concentrated upon my driving, down the winding country road from my rugged hilltop into town, speeding on the short stretches, easing around treacherous turns at great speed...

I dashed into Tom's house eight minutes after hanging up the receiver. There was a light I had observed, in the library as well as in the office, and I went straight in there and found Tom sitting on the edge of a stiff chair, plainly waiting for my arrival.

'Here I am,' said I, and laid my rifle on the library table. Tom plunged into his story...

'I'm tied up—a confinement case. They'll be calling me now any minute. Listen to this, Gerald—this is probably a new one on you—what I've got to tell you—even in the face of all the queer things you know—your West Indian experiences; vodu; all the rest of it; something I know, and—have always kept my mouth shut about! That is—if this is what I'm afraid it is. You'll have to take my word for it. I haven't lost my mind or anything of the sort—you'll probably think that if it turns out to be what I think it is—get this, now.

'Dan Curtiss's little boy, Truman, disappeared, late this afternoon, about sundown. Truman is five years old, a little fellow. He was last seen by some older kids coming back to town with berries from the Ridge, about suppertime. Little Truman, they said, was "with a lady", just outside the Old Cemetery.

'Two lambs and a calf have disappeared within the last week. Traced up there. A bone or two and a wisp of wool or so—the calf's ears, in different places, but both up there, and part of its tail; found 'em scattered around when they got up there to look.

'Some are saying "a cattymaount". Most of 'em say dogs.

'But—it isn't dogs, Gerald. "Sheep-killers" tear up their victims on the spot. They don't drag 'em three miles up a steep hill before they eat 'em. They run in a pack, too. Everybody knows that. Nothing like that has been seen—no pack, no evidences of a pack. Those lost animals have all disappeared singly—more evidence that it isn't "dogs". They've been taken up and, presumably, eaten, up on top of the Cemetery Ridge. Sheep-killing dogs don't take calves, either, and there's that calf to be accounted for. You see—I've been thinking it all out, pretty carefully. As for the catamount, well, catamounts don't, commonly, live—and eat—out in the open. A catamount would drag off a stolen animal far into the deep woods.'

I nodded.

'I've heard something about animals disappearing; only the way I heard it was that it's been going on for quite a long time, and somewhat more intensively during the past month or so.'

Tom Merritt nodded at that. 'Right,' said he. 'It's been going on ever since those Persians left, Gerald. All the time they were here—six months it was—they always bought their house supply of meat and poultry alive, "on the hoof". Presumably they preferred to kill and dress their meat themselves. I don't know, for a fact, of course. Anyhow, that was one of the peculiarities of the "foreigners up at the Canevin Place", and it got plenty of comment in the town, as you may well imagine. And—since they left—it hasn't been only lambs and calves. I know of at least four dogs. Cats, maybe, too! Nobody would keep much account of lost cats in Chadbourne.'

This, somehow, surprised me. I had failed to hear about the dogs and possible cats.

'Dogs, too, eh?' I remarked.

Then Tom Merritt got up abruptly, off his stiff chair, and came over and stood close behind me and spoke low and intensively, and very convincingly, directly into my ear.

'And now—it's a child, Gerald. That's too much—for this, or any other decent town. You've never lived in Persia. I have. I'm going to tell you in plain words what I think is going on. Try to believe me, Gerald. Literally, I mean. You've got to believe me—trust me—to do what you've got to do tonight because I can't come right now. It's going to be an ordeal for you. It would be for anybody. Listen to this, now.

'This situation only came to me, clearly, just before I called you up, Gerald. I'd been sitting here, after supper, tied up on this Grantham case—waiting for them to call me. It was little Truman Curtiss's disappearance that brought the thing to a head, of course. The whole town's buzzing with it, naturally. No such thing has ever happened here before. A child has always been perfectly safe in Chadbourne since they killed off the last Indian a hundred and fifty years ago. I hadn't seen the connection before. I've been worked to death for one thing. I naturally hadn't been very much steamed up about a few lambs and dogs dropping out of sight.

'That might mean a camp of tramps somewhere. But—tramps don't steal five-year-old kids. It isn't tramps that do kidnapping for ransom.

'It all fitted together as soon as I really put my mind on it. Those Rustum Dadhs and their unaccountable reticence—the live animals that went up to that house of yours all winter—what I'd heard, and even seen a glimpse of—out there in Kut and Shiraz—that grim-jawed, tight-lipped chauffeur of theirs, with the wife that nobody ever got a glimpse of—finally that story of little Abby Chandler—'

And the incredible remainder of what Doctor Thomas Merritt had to tell me was said literally in my ear, in a tense whisper, as though the teller were actually reluctant that the walls and chairs and books of that mellow old New England library should overhear the utterly monstrous thing he had to tell...

I was shaken when he had finished. I looked long into my lifelong friend Tom Merritt's honest eyes as he stood before me when he had finished, his two firm, capable hands resting on my two shoulders. There was conviction, certainty, in his look. There was no slightest doubt in my mind but that he believed what he had been telling me. But—could he, or anyone, by any possible chance, be right on the facts? Here, in Chadbourne, of all places on top of the globe!

'I've read about—them—in the Arabian Nights,' I managed to murmur.

Tom Merritt nodded decisively. 'I've seen—two,' he said, quietly. 'Get going, Gerald,' he added; 'it's action from now on.'

I stepped over to the table and picked up my rifle.

'And remember,' he added, as we walked across the room to the door, 'what I've told you about them. Shoot them down. Shoot to kill—if you see them. Don't hesitate. Don't wait. Don't—er—talk! No hesitation. That's the rule—in Persia. And remember how to prove it —remember the marks! You may have to prove it—to anybody who may be up there still, hunting for poor little Truman Curtiss.'

The office telephone rang.

Doctor Merritt opened the library door and looked out into the wide hallway. Then he shouted in the direction of the kitchen.

'Answer it, Mehitabel. Tell 'em I've left. It'll be Seymour Grantham, for his wife.' Then, to me: 'There are two search-parties up there, Gerald.'

And as we ran down the path from the front door to where our two cars were standing in the road I heard Doctor Merritt's elderly housekeeper at the telephone explaining in her high, nasal twang of the born Yankee, imparting the information that the doctor was on his way to the agitated Grantham family.

I drove up to the old cemetery on the Ridge even faster than I had come down from my own hill fifteen minutes earlier that evening.

The late July moon, one night away from full, bathed the fragrant hills in her clear, serene light. Halfway up the hill road to the Ridge I passed one search-party returning. I encountered the other coming out of the cemetery gate as I stopped my steaming engine and set my brakes in front of the entrance. The three men of this party, armed with a lantern, a rifle, and two sizable clubs, gathered around me. The youngest, Jed Peters, was the first to speak. It was precisely in the spirit of Chadbourne that this first remark should have no direct reference to the pressing affair motivating all of us. Jed had pointed to my rifle, interest registered plainly in his heavy, honest countenance.

'Some weepon—thet-thar, I'd reckon, Mr. Canevin.'

I have had a long experience with my Chadbourne neighbors.

'It's a Männlicher,' said I, 'what is called "a weapon of precision". It is accurate to the point of nicking the head off a pin up to about fourteen hundred yards.'

These three fellows, one of them the uncle of the missing child, had discovered nothing. They turned back with me, however, without being asked. I could have excused them very gladly. After what Tom Merritt had told me, I should have preferred being left alone to deal with the situation unaided. There was no avoiding it, however. I suggested splitting up the party and had the satisfaction of seeing this suggestion put into effect. The three of them walked off slowly to the left while I waited, standing inside the cemetery gate, until I could just hear their voices.

Then I took up my stand with my back against the inside of the cemetery wall, directly opposite the big Merritt family mausoleum.

The strong moonlight made it stand out clearly. I leaned against the stone wall, my rifle cuddled in my arms, and waited. I made no attempt to watch the mausoleum continuously, but ranged with my eyes over the major portion of the cemetery, an area which, being only slightly shrubbed, and sloping upward gently from the entrance, was plainly visible. From time to time as I stood there, ready, I would catch a faint snatch of the continuous conversation going on among the three searchers, as they walked along on a long course which I had suggested to them, all the way around the cemetery, designed to cover territory which, in the local phraseology, ran 'down through', 'up across', and 'over around'. I had been waiting, and the three searchers had been meandering, for perhaps twenty minutes—the ancient town clock in the Congregational church tower had boomed ten about five minutes before—when I heard a soft, grating sound in the direction of the Merritt mausoleum. My eyes came back to it sharply.

There, directly before the now half-open bronze door, stood a strange, even a grotesque, figure. It was short, squat, thickset. Upon it, I might say accurately, hung—as though pulled on in the most hurried and slack fashion imaginable—a coat and trousers. The moonlight showed it up clearly and it was plain, even in such a light, that these two were the only garments in use. The trousers hung slackly, bagging thickly over a pair of large bare feet. The coat, unbuttoned, sagged and slithered lopsidedly. The coat and trousers were the standardized, unmistakable, diagonal gray material of a chauffeur's livery. The head was bare and on it a heavy, bristle-like crop of unkempt hair stood out absurdly. The face was covered with an equally bristle-like growth, unshaven for a month by the appearance. About the tight-shut, menacing mouth which divided a pair of square, iron-like broad jaws, the facial hairs were merged or blended in what seemed from my viewpoint a kind of vague smear, as though the hair were there heavily matted.

From this sinister figure there then emerged a thick, guttural, repressed voice, as though the speaker were trying to express himself in words without opening his lips.

'Come—come he-ar. Come—I will show you what you look for.'

Through my head went everything that Tom Merritt had whispered in my ear. This was my test—my test, with a very great deal at stake—of my trust in what he had said—in him—in the rightness of his information; and it had been information, based on his deduction, such as few men have had to decide upon. I said a brief prayer in that space of a few instants. I observed that the figure was slowly approaching me.

'Come,' it repeated —'come now—I show you—what you, a-seek—here.'

I pulled myself together. I placed my confidence, and my future, in Tom Merritt's hands.

I raised my Männlicher, took careful aim, pulled the trigger. I repeated the shot. Two sharp cracks rang out on that still summer air, and then I lowered the deadly little weapon and watched while the figure crumpled and sagged down, two little holes one beside the other in its forehead, from which a dark stain was spreading over the bristly face, matting it all together the way the region of the mouth had looked even before it lay quiet and crumpled up on the ground halfway between the mausoleum and where I stood.

I had done it. I had done what Tom Merritt had told me to do, ruthlessly, without any hesitation, the way Tom had said they did it in Persia around Teheran, the capital, and Shiraz, and in Kut-el-Amara, and down south in Jask.

And then, having burned my bridges, and, for all I knew positively, made myself eligible for a noose at Wethersfield, I walked across to the mausoleum, and straight up to the opened bronze door, and looked inside.

A frightful smell—a smell like all the decayed meat in the world all together in one place—took me by the throat. A wave of quick nausea invaded me. But I stood my ground, and forced myself to envisage what was inside; and when I had seen, despite my short retchings and coughings I resolutely raised my Männlicher and shot and shot and shot at moving, scampering targets; shot again and again and again, until nothing moved inside there. I had seen, besides those moving targets, something else; some things that I will not attempt to describe beyond using the word 'fragments'. Poor little five-year-old Truman Curtiss who had last been seen just outside the cemetery gate 'with a lady' would never climb that hill again, never pick any more blueberries in Chadbourn or any other place...

I looked without regret on the shambles I had wrought within the old Merritt tomb. The Männlicher is a weapon of precision...

I was brought to a sense of things going on outside the tomb by the sound of running feet, the insistent, clipping drawl of three excited voices asking questions. The three searchers, snapped out of their leisurely walk around the cemetery, and quite near by at the time my shooting had begun, had arrived on the scene of action.

'What's it all about, Mr. Canevin?'

'We heard ye a-shootin' away.'

'Good Cripes! Gerald's shot a man!'

I blew the smoke out of the barrel of my Männlicher, withdrew the clip. I walked toward the group bending now over the crumpled figure on the ground halfway to the cemetery gate.

'Who's this man you shot, Gerald? Good Cripes! It's the fella that druv the car for them-there Persians. Good Cripes, Gerald—are ye crazy? You can't shoot down a man like that!'

'It's not a man,' said I, coming up to them and looking down on the figure.

There was a joint explosion at that. I waited, standing quietly by, until they had exhausted themselves. They were, plainly, more concerned with what consequences I should have to suffer than with the fate of the chauffeur.

'You say it ain't no man! Are ye crazy, Gerald?'

'It's not a man,' I repeated. 'Reach down and press his jaws together so that he opens his mouth, and you'll see what I mean.'

Then, as they naturally enough I suppose hesitated to fill this order, I stooped down, pressed together the buccinator muscles in the middle of the broad Mongol-like cheeks. The mouth came open, and thereat there was another chorus from the three. It was just as Tom Merritt had described it! The teeth were the teeth of one of the great carnivores, only flat, fang-like, like a shark's teeth. No mortal man ever wore such a set within his mouth, or ever needed such a set, the fangs of a tearer of flesh...

'Roll him over,' said I, 'and loosen that coat so you can see his back.'

To this task young Jed addressed himself.

'Good Cripes!' This from the Curtiss fellow, the lost child's uncle. Along the back, sewn thickly in the dark brown skin, ran a band of three-inch, coal-black bristles, longer and stiffer than those of any prize hog. We gazed down in silence for a long moment. Then: 'Come,' said I, 'and look inside the Merritt tomb—but—brace yourselves! It won't be any pleasant sight.'

I turned, led the way, the others falling in behind me. Then, from young Jed Peters: 'You say this-here ain't no man—an'—I believe ye, Mr. Canevin! But—Cripes Almighty!—ef this'n hain't no man, what, a-God's Name, is it?'

'It is a ghoul,' said I over my shoulder, 'and inside the tomb there are ten more of them—the dam and nine whelps. And what is left of the poor little Curtiss child... '

Looking into the mausoleum that second time, in cold blood, so to speak, was a tough experience even for me who had wrought that havoc in there. As for the others—Eli Curtiss, the oldest of the three, was very sick. Bert Blatchford buried his face in his arms against the door's lintel, and when I shook him by the shoulder in fear lest he collapse, the face he turned to me was blank and ghastly, and his ruddy cheeks had gone the color of lead.

Only young Jed Peters really stood up to it. He simply swore roundly, repeating his 'Good Cripes!' over and over again—an articulate youth.

The whelps, with their flattish, humanlike faces and heads, equipped with those same punishing, overmuscled jaws like their sire's—like the jaws of a fighting bulldog—their short, thick legs and arms, and their narrow, bristly backs, resembled young pigs more nearly than human infants. All, being of one litter, were of about the same size; all were sickeningly bloody-mouthed from their recent feast. These things lay scattered about the large, circular, marble-walled chamber where they had dropped under the merciless impacts of my bullets.

Near the entrance lay sprawled the repulsive, heavy carcass of the dam, her dreadful, fanged mouth open, her sow-like double row of dugs uppermost, these dragged flaccid and purplish and horrible from the recent nursing of that lately-weaned litter. All these unearthly-looking carcasses were naked. The frightful stench still prevailed, still poured out through the open doorway. Heaps and mounds of nauseous offal cluttered the place.

It was young Jed who grasped first and most firmly my suggestion that these horrors be buried out of sight, that a curtain of silence should be drawn down tight by the four of us, fastened permanently against any utterance of the dreadful things we had seen that night. It was young Jed who organized the three into a digging party, who fetched the grave tools from the unfastened cemetery shed.

We worked in a complete silence, as fast as we could. It was not until we were hastily throwing back the loose earth over what we had placed in the sizable pit we had made that the sound of a car's engine, coming up the hill, caused our first pause. We listened.

'It's Doctor Merritt's car,' I said, somewhat relieved. I looked at my wrist-watch. It was a quarter past midnight.

To the four of us, leaning there on our spades, Doctor Merritt repeated something of the history of the Persian tombs, a little of what he had come to know of those mysterious, semi-mythical dwellers among the half-forgotten crypts of ancient burial-grounds, eaters of the dead, which yet preferred the bodies of the living, furtive shapes shot down when glimpsed—in ancient, mysterious Persia...

I left my own car for the three fellows to get home in, young Jed promising to have it back in my garage later in the morning, and drove home with Doctor Merritt.

'There was another thing which I didn't take the time to tell you,' said Tom, as we slipped down the winding hill road under the pouring moonlight. 'That was that the Rustum Dadh's servants were never seen to leave Chadbourne; although, of course, it was assumed that they had done so. The family went by train. I went down to the station to see them off and I found old Rustum Dadh even less communicative than usual.

' "I suppose your man is driving your car down to New York," I said. It had arrived, six months before, when they came to Chadbourne, with both the servants in it, and the inside all piled up with the family's belongings. The old boy merely grunted unintelligibly, in a way he had.

'That afternoon, when I went up to your place to see that everything was shipshape, there stood the car in the garage, empty. And, while I was wondering what had become of the chauffeur and his wife, and why they hadn't been sent off in the car the way they came, up drives Bartholomew Wade from his garage, and he has the car-key and a letter from Rustum Dadh with directions, and a check for ten dollars and his carfare back from New York. His instructions were to drive the car to New York and leave it there. He did so that afternoon.'

'What was the New York address?' I inquired. 'That might take some looking into, if you think—'

'I don't know what to think—about Rustum Dadh's connection with it all, Gerald,' said Tom. 'The address was merely the Cunard Line Docks. Whether Rustum Dadh and his family were—the same—there's simply no telling. There's the evidence of the live animals sent up to the house. That live meat may have been for the chauffer and his wife—seems unlikely, somehow. There was a rumor around town about some dispute or argument between the old man and his chauffeur, over their leaving all together—just a rumor, something picked up or overheard by some busybody. You can take that for what it's worth, of course. The two of 'em, desirous to break away from civilization, revert, here in Chadbourne—that, I imagine, is the probability. There are many times the number of people below ground in the three old cemeteries than going about their affairs—and other people's!—here in Chadbourne. But, whatever Rustum Dadh's connection with—what we know—whatever share of guilt rests on him—he's gone, Gerald, and we can make any one of the three or four possible guesses; but it won't get us anywhere.' Then, a little weariness showing in his voice, for Tom Merritt, too, had had a pretty strenuous evening, he added: 'I hired young Jed Peters to spend tomorrow cleaning out the old tombhouse of the ancestors!'

I cleaned my rifle before turning in that night. When I had got this job done and had taken a boiling-hot shower-bath, it was close to two o'clock a.m. before I rolled in between the sheets. I had been dreading a sleepless night with the edge of my mind, after that experience up there on the Old Cemetery Ridge. I lay in bed for a while, wakeful, going over snatches of it in my mind. Young Jed! No deterioration there at any rate. There was a fellow who would stand by you in a pinch. The old yeoman stock had not run down appreciably in young Jed.

I fell asleep at last after assuring myself all over again that I had done a thorough job up there on the hill. Ghouls! Not merely Arabian Nights creatures, like the Afreets and the Djinn. No. Real—those jaws! They shot them down, on sight, over there in Persia when they were descried coming out of their holes among the old tomb-places...

Little, reddish, half-gnawed bones, scattered about that fetid shambles—little bones that had never been torn out of the bodies of calves or lambs—little bones that had been—

I wonder if I shall ever be able to forget those little bones, those little, pitiful bones...

I awoke to the purr of an automobile engine in second speed, coming up the steep hill to my farmhouse, and it was a glorious late-summer New England morning. Young Jed Peters was arriving with my returned car.

I jumped out of bed, pulled on a bathrobe, stepped into a pair of slippers. It was seven-thirty. I went out to the garage and brought young Jed back inside with me for a cup of coffee. It started that new day propitiously to see the boy eat three fried eggs and seven pieces of breakfast bacon...

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.