RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

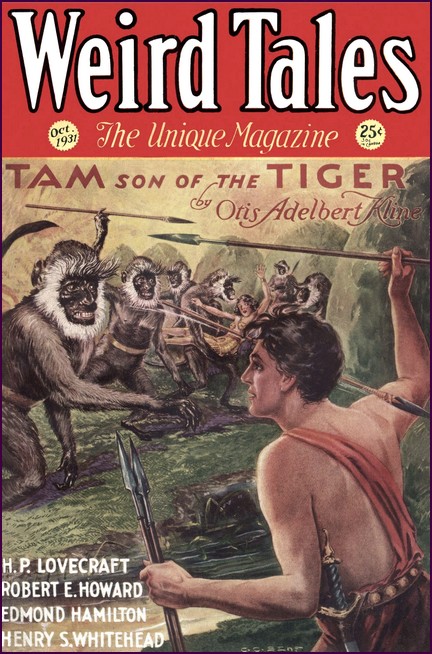

Weird Tales, October 1931, with "Black Terror">

A story of vodu—on the West Indian Island of Santa Cruz strange beliefs can cause death from sheer terror.

I WOKE up in the great mahogany bed of my house in Christiansted with an acute sense of something horribly wrong, something frightful, tearing at my mind. I pulled myself together, shook my head to get the sleep out of my eyes, pulled aside the mosquito-netting. That was better! The strange sense of horror which had pursued me out of sleep was fading now.

I groped vaguely, back into the dream, or whatever it had been—it did not seem to have been a dream; it was something else. I could now, somehow, localize it. I found now that I was listening, painfully, to a sustained, aching sound, like a steam calliope fastened onto one high, piercing, raucous note. I knew it could not be a steam calliope. There had been no such thing on the Island of Santa Cruz since Columbus discovered it on his Second Voyage in 1493. I got up and into my slippers and muslin bathrobe, still puzzled.

Then abruptly the note ended, cut off clean like the ceasing of the drums when the Black people are having one of their ratas back of the town in the hills.

Then, and only then, I knew what it was that had disturbed me. It had been a woman, screaming.

I ran out to the semi-enclosed gallery which runs along the front of my house on the Copagnie Gade, the street of hard-pounded earth below, and looked down.

A group of early risen Blacks in nondescript garb was assembled down there, and the number was increasing every instant. Men, women, small Black children were gathered in a rapidly tightening knot directly in front of the house, their guttural mumbles of excitement forming a contrapuntal background to the solo of that sustained scream; for the woman, there in the center, was at it again now, with fresh breath, uttering her blood-curdling, hopeless, screeching wail, a thing to make the listener wince.

Not one of the throng of Blacks touched the woman in their midst. I listened to their guttural Creole, trying to catch some clue to what this disturbance was about. I would catch a word of the broad patois here and there, but nothing my mind could lay hold upon. At last it came, the clue; in a childish, piping treble; the clear-cut word, Jumbee.

I had it now. The screaming woman believed, and the crowd about her believed, that some evil witchery was afoot. Some enemy had enlisted the services of the dreaded witch-doctor—the papaloi—and something fearful, some curse or charm, had been 'put on' her or someone belonging to her family. All that the word 'Jumbee' had told me clearly.

I watched now for whatever was going to happen. Meanwhile I wondered why a policeman did not come along and break up this public gathering. Of course the policeman, being a Black man himself, would be as much intrigued as any of the others, but he would do his duty nevertheless. 'Put a Black to drive a Black!' The old adage was as true nowadays as in the remote days of West Indian slavery.

The woman, now convulsed, rocking backward and forward, seemed as though possessed. Her screams had now an undertone or cadence of pure horror. It was ghastly.

A policeman, at last! Two policemen, in fact, one of them Old Kraft, once a Danish top-sergeant of garrison troops. Kraft was nearly pure Caucasian, but, despite his touch of African, he would tolerate no nonsense. He advanced, waving his truncheon threateningly, barking hoarse reproaches, commands to disperse. The group of Black people began to melt away in the general direction of the Sunday Market, herded along by Sergeant Kraft's dark brown patrolman.

Now only Old Kraft and the Black woman who had screamed remained, facing each other in the street below. I saw the old man's face change out of its harsh, professional, manhandling frown to something distinctly more humane. He spoke to the woman in low tones. She answered him in mutters, not unwillingly, but as though to avoid being overheard.

I spoke from the gallery.

'What is it, Herr Kraft? Can I be of assistance?'

Old Kraft looked, recognized me, touched his cap.

'Stoopide-ness!' exploded Old Kraft, explanatorily. 'The woo-man, she haf had—' Old Kraft paused and made a sudden, stiff, dramatic gesture and looked at me meaningly. His eyes said: 'I could tell you all about it, but not from here.'

'A chair on the gallery for the poor woman?' I suggested, nodding to him.

'Come!' said he to the woman, and she followed him obediently up the outside gallery steps while I walked across to unfasten the door at the gallery's end.

We placed the woman, who seemed dazed now and kept a hand on her head, in one of my chairs, where she rocked slowly back and forth whispering to herself, and Kraft and I went inside the house, where I led him through to the dining-room.

There, at the sideboard, I did the honors for my friend Sergeant Kraft of the Christiansted Police.

'The woman's screaming awakened me, half an hour early,' I began, invitingly, as soon as the sergeant had been duly refreshed and had said his final 'skoal', his eyes on mine in the Danish manner.

'Yah, yah,' returned Kraft, nodding a wise old head. 'She tell me de Obiman fix her right, dis time!'

This sounded promising. I waited for more.

'But joost what it iss, I can not tell at all,' continued Kraft, disappointingly, as though aware of the secretiveness which should animate a police sergeant.

'Will you have—another, Herr Kraft?' I suggested.

The sergeant obliged, ending the ceremony with another 'skoal'. This libation, as I had hoped, had the desired effect. I will spare Kraft's accent, which could be cut with a knife. What he told me was that this woman, Elizabeth Aagaard, living in a village estate-cabin near the Central Factory, a few miles outside of Christiansted, had a son, one Cornelis McBean. The young fellow was what is locally known as a 'gallows-bird,' in short a gambler, thief, and general bad-egg. He had been in the police court several times for petty offenses, and in jail in the Christiansfort more than once.

But, as Kraft expressed it, 'it ain' de thievin' dat make de present difficoolty.' No! it was that young Cornelis McBean had presumed beyond his station, and had committed the crime of falling in love with Estrella Collins, the daughter of a prosperous Black storekeeper in one of Christiansted's side streets. Old Collins, utterly disapproving, and his words to McBean having had no effect whatever upon that stubborn lover, had, in short, employed the services of a papaloi to get rid of McBean.

'But,' I protested, 'I know Old Collins. I understand, of course, how he might object to the attentions of such a young ne'er-do-well, but—a storekeeper like him, a comparatively rich man, to call in a papaloi—it seems—'

'Him Black!' replied Sergeant Kraft with a little, significant gesture which made everything plain.

'What,' said I, after thinking a little, 'what particular kind of ouanga has Collins had "put on" him?'

The old sergeant gave me a quick glance at that word. It is a meaningful word. In Haiti it is very common. It means both talisman and amulet; something, that is, to attract, or something to repel, to defend the wearer. But here in Santa Cruz the magic of our Blacks is neither so clear-cut nor (as some imagine) quite so deadly as the magickings of the papalois and the hougans in Haiti's infested hills with their thousands of vodu altars to Ougoun Badagaris, to Damballa, to the Snake of far, dreadful Guinea. Over even so much as the manufacture of ouangas I may not linger. One can not. The details—

'It is, I think, a "sweat-ouanga,"' whispered Old Kraft, and went a shade lighter than his accustomed sunburned ivory. 'De wooman allege,' he continued, 'that the boy sicken an' die at noon—today. For that reason she is walk into de town early, because there is no help. She desire to bewail-like, dis trouble restin' 'pon her head.'

Kraft had given me all the information he possessed. He rated a reward. I approached the sideboard a third time.

'You will excuse me again, Sergeant. It is a little early in the day for me. Still, "a man can't walk on one leg!"'

The sergeant grinned at this Santa Crucian proverb which means that a final stirrup-cup is always justified, and remarked: 'He should walk goot—on three!' After this reference to the number of his early-morning refreshments, he accepted the last of these, boomed his 'skoal', and became a police sergeant once more.

'Shall I take de wooman along, sir?' he inquired as we reached the gallery where Elizabeth Aagaard still rocked and moaned and whispered to herself in her trouble.

'Leave her here, please,' I replied, 'and I will see that Esmerelda finds her something to eat.' The sergeant saluted and departed.

'Gahd bless yo', sar,' murmured the poor soul. I left her there and went to the kitchen to drop a word in the sympathetic ear of my old cook. Then I started toward my belated shower-bath. It was nearly seven by now.

After breakfast I inquired for Elizabeth Aagaard. She had had food and had delivered herself at length upon her sorrows to Esmerelda and the other house-servants. Esmerelda's account established the belief that young McBean had been marked for death by one of the oldest and deadliest devices known to primitive barbarism; one which, as all Caucasians who know of it will assure you, derives its sole efficacy from the psychology of fear, that fear of the occult which has stultified the African's mind through countless generations of warfare against the jungle and the dominance of his fetish-men and vodu priests.

As is well known to all students of African 'magic', portions of the human body, such as hair, the clippings of nails, or even some garment long worn in contact with the body, is regarded as having a magical connection with the body itself and a corresponding influence upon it. A portion of the shirt which has been worn next the body and which has absorbed perspiration is especially highly regarded as material for the making of a protective charm or amulet, as well as for its opposite, planted against a person for the purpose of doing him harm. Blood, etc., could be included in this weird category.

In the case of young Cornelis McBean, this is what had been done. The papaloi had managed to get hold of one of Cornelis' shirts. In this he had dressed the recently buried body of an aged negro who had died a few days before, of senility. This shirt, after it had been in the coffin for three days and nights, had been cunningly put back for Cornelis to find and wear again. It had been, supposedly, mislaid. Young McBean, finding it in his mother's cabin, had worn it again.

And, as if this, in itself enough to cause his death from sheer terror as soon as he knew of it, was not sufficient, it had just come to the knowledge of the mother and son by the curious African method known as the Grapevine Route, that a small ouanga, made up of some of Cornelis' nail-parings, stubble of a week's beard collected from discarded lather after shaving, various other portions of his exterior personality, had been 'fixed' by the Christiansted papaloi, and 'buried against him'.

This meant that unless the ouanga could be discovered and dug up and burned, he would die at noon. As he had learned of the 'burying' of the ouanga only the evening before, and as the Island of Santa Cruz has an area of more than eighty square miles, there was, perhaps, one chance in some hundred trillion that he could find the ouanga, disinter it, and render it harmless by burning. Taking into consideration that his ancestors for countless eons had given their full and firm belief to this method of murder by mental process, it looked as though young Cornelis McBean, ne'er-do-well, Black island gallow's-bird, aspiring admirer of a young negress somewhat beyond his station in life according to African West Indian caste systems, was doomed to pass out on the stroke of twelve that day.

That, with an infinitude of detail, was the substance of the story of Elizabeth Aagaard.

I sat and looked at her, quiet and humble now, no longer the screaming fury she had appeared to be at that morning's crack of dawn. And as I looked at the poor soul, with the dumb, distressed motherhood in her dim eyes from which the unchecked tears ran down her coal-black face, it came to me that I wanted to help; that this thing was outrageous; wicked with a wickedness far surpassing the ordinary sinfulness of ordinary people. I did not want to sit by, as it were, and allow the unknown McBean to pass out at the behest of a paid rascal of a papaloi merely because unctuous Old Collins had decided on that method for his exit from this life—a matter involving, perhaps fifteen dollars' fee to the witch-doctor; the collection and burial of some bits of offal somewhere on Santa Cruz.

I could imagine the young Black fellow, livid with a nameless fear, a complex of ancient, inherited, unreasonable dreads, shivering, cowering, sickened to his dim soul by what lay ahead of him, three hours away when twelve should strike from the Christiansfort clock in the old tower by the harbor; writhing helplessly in his mind before the approach of the ghastly doom which he had brought upon himself because he had happened to fall in love with brown Estrella Collins, whose sleek brown father carried a collection-plate every Sunday up and down the aisle of his place of worship!

There was an element of absurdity in it all, now that I was actually sitting here looking at McBean's mother. She had given up now, it appeared, was resigned to the fate of her only son. 'Him Black!' Old Kraft had remarked.

That thought of the collection-plate in Old Collins' pudgy, storekeeper's hands, reminded me of something.

'What is your church, Elizabeth?' I inquired suddenly.

'Me English Choorch, sar—de boy also. Him make great shandramadan, sar, him gamble an' perhaps a tief, but him one-time communicant, sar.'

An inspiration came to me then. Perhaps I could prevail upon one of the English Church clergy to help. It was, when one came down to the brass tacks of the situation, a question of belief. A similar ouanga, 'buried against' me, would have no effect whatever, because to me, such a means of getting rid of a person was merely the height of absurdity, like the charm-killing of the Polynesians by making them look at their reflection in a gourd of water and then shaking the gourd and so destroying the image! Perhaps, if Elizabeth and her son could be persuaded to do their parts... I spoke long and earnestly to Elizabeth.

At the end of my speech, which had emphasized the superior power of Divinity when compared to even the most powerful of the African fetishes, even the dreaded snake himself, Elizabeth, her hopes somewhat aroused, I imagined, took her departure, and I jumped into my car and ran up the hill toward the English Church rectory.

Father Richardson, the pastor, himself a West Indian born, was at home. To him I explained the case. When I had ended—

'I am obliged to you, Mr. Canevin,' said the clergyman. 'If only they would realize—er—precisely what you told the woman; that Divinity is infinitely more powerful than their beliefs! I will accompany you, at once. It is, really, the release, perhaps, of a human soul. And they come to us clergy over such things as the theft of a couple of coconuts!'

Father Richardson left me, came back in two minutes with a black bag, and we started for Elizabeth Aagaard's village along a lovely shore road by the gleaming, placid, blue Caribbean.

The negro estate-village was surprisingly quiet when we arrived. The clergyman got out at Elizabeth's cabin, and I drove the car out of the way, off the road into rank guinea-grass. I saw Father Richardson, a commanding, tall figure, austere in his long, black cassock, striding in at the cabin door. I followed, and got inside just in time to witness a strange performance.

The Black boy, livid and seeming shrunken with terror, cowered under a thin blanket on a small iron bedstead. Over him towered the clergyman, and just as I came in, he stooped and with a small, sharp pocketknife cut something loose from the boy's neck and flung it contemptuously on the hard-earth floor of the cabin. It landed just at my feet and I looked at it curiously. It was a small black bag, of some kind of cotton material, with a tuft of black cock's feathers at its top which was bound around with many windings of bright red thread. The whole thing was about the size of an egg. I recognized it as a protective amulet.

His teeth chattering, the cold fear of death upon him, the Black boy protested in the guttural Creole. The clergyman answered him gravely.

'There can be no halfway measures, Cornelis. When a person asks God for His help, he must put away everything else.' A mutter of assent came from the woman, who was arranging a small table with a candle in the corner of the cabin.

From his black bag Father Richardson now took a small bottle with a sprinkler arrangement at its top, and from this he cast a shower of drops upon the ouanga charm lying on the floor. Then he proceeded to sprinkle the whole cabin with this holy water, ending with Elizabeth, myself, and finally, the boy on the bed. As the water touched his face the boy winced visibly and shuddered; and suddenly it came over me that here was a strange matter; again, I dare say, a matter of belief. The change from the supposed protection of the charm which the priest had cut away from his neck and contemptuously tossed away, to the prescribed method of the Church must have been, somehow, and in some obscure mental fashion, a very striking one to the young fellow.

The bottle went back into the bag and now Father Richardson was speaking to the boy on the bed.

'God is intervening for you, my child, and—God's power is supreme over all things, visible and invisible. He holds all in the hollow of His hand. He will now put away your fear, and take this weight from your soul, and you shall live. You must now do your part, if you would be fortified by the Sacrament. You just purify your soul. Penance first. Then—'

The boy, now appreciably calmer, nodded his head, and the priest motioned me out, including the woman in his gesture. I opened the cabin door and stepped out, closely followed by Elizabeth Aagaard. I left her, twenty paces from her cabin, wringing her hands, her lips murmuring in prayer, while I went and sat in my car.

Ten minutes later the cabin door opened and the priest beckoned us within. The boy lay quiet now, and Father Richardson was engaged in repacking his black bag. He turned to me: 'Goodbye, and—thank you. It was very good of you to bring me.'

'But—aren't you coming?'

'No'—this reflectively. 'No—I must see him through.' He glanced at his wrist-watch. 'It is eleven-fifteen now. It was at noon you said—'

'I'm staying with you, then,' said I, and sat down on a chair in the far corner of the little cabin room.

The priest stood by the bedside, looking down at the Black boy, his back to me. The woman was, apparently, praying earnestly to herself in another corner, out of the way. The priest stooped and took the limp hand and wrist in his large, firm white hands, and counted the pulse, glancing at his watch. Then he came and sat beside me.

'Half an hour!' he murmured.

The Black woman, Elizabeth, prayed without a sound in her corner on the hard, earth floor, where she knelt, rigidly. We sat, without conversation, for a long twenty minutes during which the sense of strain in the cabin became more and more apparent to me.

Abruptly the boy's mouth fell open. The priest sprang toward him, seized and chafed the dull-black hands. The boy's head turned on the pillow and his jaws came together again, his eyelids fluttering. Then a slight spasm, perceptible through the light covering, ran through him, and, breathing a few times deeply, he resumed his coma-like sleep. The priest now remained beside him. I counted off the minutes to noon. Nine—eight—seven—at least, three minutes before noon. When I had got that far I heard the priest's deep, monotonous voice reciting in a low tone. Listening, I caught his words here and there. He held the boy's hand while the words rolled out low and impressively.

'... to withstand and overcome all assaults of thine adversary... unto thee ghostly strength... and that he nowise prevail against thee.' Then, dropping a note, to my surprise, the clerical voice of this most Anglican of clergymen began to declaim the words of an older liturgical language: '... et effugiat atque discedat omnis phantasia et nequitia... vel versutia diabolicae fraudis omnisque spiritus immundis adjuratis... '

The words, gaining in volume with the priest's earnestness, rolled out now. I saw that we were on the very verge of noon, and, looking back to the bed from my glance at my watch, I saw convulsion after convulsion shake the thin body on the bed. Then the cabin itself began to tremble in a sudden wind that had sprung up from nowhere. The dry palm fronds lashed back and forth outside and the whistle of the wind blew under the crazily hung door. The muslin curtain of the small window suddenly billowed like a sail. Then, suddenly, the harsh voice of the Black boy.

'Damballa!' it said, clearly, and moaned.

Damballa is one of the Greater Mysteries of the vodu worship. I shuddered in spite of myself.

But now higher, more commanding, came the voice of Father Richardson, positively intoning now—great sentences of Power, formulas interposed, as he himself stood, interposed, between the feeble Black boy and the Powers of Evil which seemed to seek him out for their own fell ends. The priest seemed to stretch a mantle of mystic protection over the grovelling, writhing body.

The mother lay prone on the dirt floor, now, her arms stretched out crosslike—the last, most abject gesture of supplication of which humanity is physically capable. As I glanced down at her I saw, in the extreme corner of the little room, something oddly shaped projecting from a pile of discarded garments.

It was now exactly noon. As I looked carefully at my watch, the distant stroke of the Angelus came resoundingly from the heavy bell of St John's Church. Father Richardson ceased his recitation, laid back the boys hand on the coverlid, and began the Angelus. I stood up at this, and, as he finished, I plucked his sleeve. The wind, curiously enough, was gone, utterly. Only the noon sun beat down suffocatingly on the iron roof of the frail cabin. Father Richardson looked at me inquiringly. I pointed to that corner, under the pile of clothes. He walked to the corner, stooped, and drew out a crude wooden image of a snake. He glanced accusingly at Elizabeth, who grovelled afresh.

'Take it up, Elizabeth,' commanded Father Richardson, 'break it in two, and throw it out of the doorway.'

The woman crawled to the corner, lifted the thing, snapped it in two, and then, rising, her face gray with fear, opened the cabin door and threw out the pieces. We went back to the bedside, where the boy breathed quietly now. The priest shook him. He opened swimming eyes, eyes like a drunken man's. He goggled stupidly at us.

'You are alive—by the mercy of God,' said the priest, severely. 'Come now, get up! It is well past noon. Here! Mr. Canevin will show you his watch. You are not dead. Let this be a lesson to you to leave alone what God has put outside your knowledge.'

The boy sat up, still stupidly, the thin blanket drawn about him, on the side of the bed.

'We may as well drive back now,' said Father Richardson, picking up his black bag in a businesslike manner.

As I turned my car to the right just outside the estate-village stone gateway, I glanced back toward the village. It swarmed with Blacks, all crowding about the cabin of Elizabeth Aagaard. Beside me, I heard the rather monotonous voice of Father Richardson. He seemed to be talking to himself; thinking aloud, perhaps.

'Creator—of all things—visible and invisible.'

I drove slowly to avoid the ducks, fowls, small pigs, pickaninnies and burro-carts between the edge of town and the rectory.

'It was,' said I, as I held his hand at parting, 'an experience—that.'

'Oh—that! Yes, yes, quite! I was thinking—you'll excuse me, Mr. Canevin—of my afternon sick-calls. My curate isn't quite over that last attack of dengue fever. I have a full afternoon. Come in and have tea with us—any afternoon, about five.'

I drove home slowly. A West Indian priest! That sudden wind—the little wooden snake—the abject fear in the eyes of the Black boy! All that had been merely in the day's work for Father Richardson, in those rather awkward, large, square hands, the hands which held the Sacrament every morning. Sometimes I would get up early and go to church myself on a weekday morning, along the soft roads through the pre-dawn dusk along with scores of soft-stepping, barefooted Blacks, plodding to church in the early dawn, going to get strength, power, to fight the age-long battle between God and Satan—the Snake—here where the sons of Ham tremble beneath the lingering fears of that primeval curse which came upon their ancestor because he dared to laugh at his father Noah.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.